Unassuming in his conduct, Kung Te-cheng, direct descendant of Confucius' and former Examination Yuan president, rarely accepts media interviews. Kung was awarded an honorary doctorate from National Taiwan University at the end of last year, and on the day of the conferral, NTU president Lee Si-Chen commended him for disseminating Confucian culture and for guiding anthropology and Chinese literature students in reviving ancient rites, a project that exemplified the integration of technology. During the ceremony Kung declared, in his self-effacing manner, that his contributions during his 50 years of teaching at NTU were few and that he felt great shame, but that he was heartened and encouraged by NTU's motto: "Cultivate virtue, advance intellect; love one's country, love one's people."

In 1950 Kung followed the Nationalist government's withdrawal to Taiwan; since then he has not returned to his hometown in mainland China. In recent years the Chinese government has founded several Confucius Institutes around the world, quite contrary to its "criticize Confucius and praise Qin Shihuang" policy during the Cultural Revolution. Besides expressing pleasure at this dissemination of Chinese culture, Kung avoids talking about political subjects. Even during the joyful occasion of this year's birth of Confucius' 80th-generation progeny--Kung Yu-jen--it was his daughter-in-law who made the statements.

"Mr. Kung Te-cheng's discretion in words and deeds may be related to the setting into which he was born," says Tung Chin-yue, professor of Chinese Literature at National Chengchi University. Kung was born in 1920, but his father Kung Ling-i died of illness three months before his birth. The issue of whether the Kung family's last child would be a boy or a girl drew the attention of the entire nation at that time. Since Kung Ling-i's wife had not yet produced a male heir and his concubine had only borne him two daughters, if the last child were to be a girl, there would be no successor to the hereditary title of Duke Yansheng, and the great prestige and wealth of the House of Kung would trigger a struggle for succession. Kung Te-cheng was thus born under the full protection of the Beiyang government.

As described in 100 Biographies of the Republican Era, "As news of Kung Te-cheng's birth spread, the sound of firecrackers rang throughout the city of Qufu in celebration of this much longed-for boy."

Kung Te-cheng was born amid the turmoil of the May Fourth Movement, with its rejection of Confucian ideology, yet the Kung family's prestige still held an irreplaceable standing. A glimpse of such status may be seen from the time the Qianlong Emperor sought the union of the Imperial Family and the House of Kung. It is said that Qianlong's daughter was cursed due to an inauspicious mole on her face. To stave off disaster, he wished for the princess to marry into the Kung family. Hampered by the Qing court's ban on Manchu-Han intermarriage, the Emperor, out of love for his daughter, had one of his Han ministers adopt her, allowing the marriage to proceed under her new identity as a daughter of a Han family.

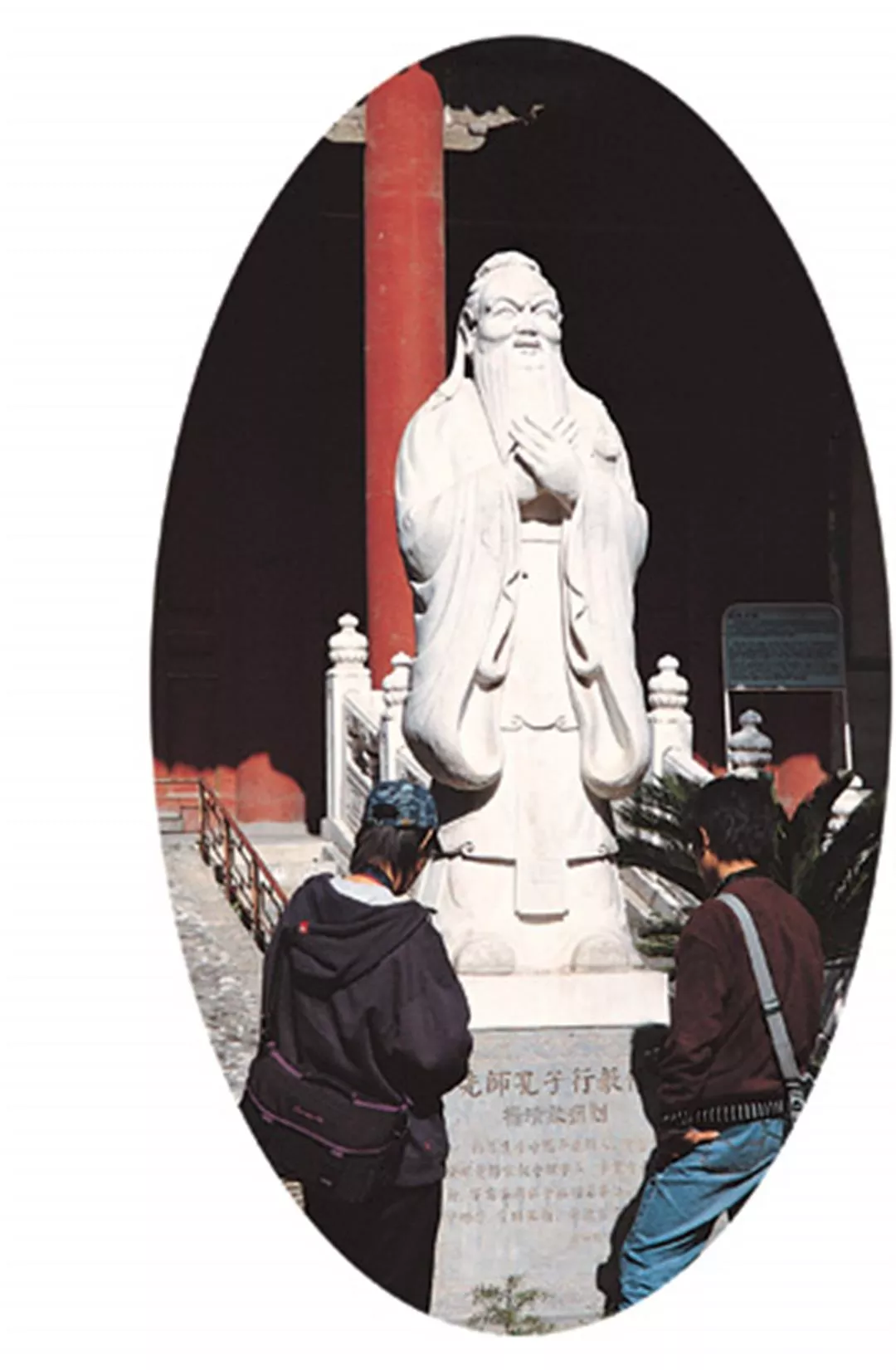

Confucius' 79th-generation descendant Kung Chui-chang, holding his son Kung Yu-jen. Chui-chang's father has predeceased him, making him the heir apparent to the ceremonial post of Sacrificial Official to Confucius.