A race in which no one can move

With a health care network as yet incomplete, is the burden of creating a universal health insurance plan inevitably too heavy to bear? Honestly, in this atmosphere of hesitancy and doubt which prevails among public officials, the medical community and patients alike, "Let's take things one step at a time" has become the standard answer of nearly every interviewee. Fortunately, Yeh Chin-chuan, who shoulders the greatest responsibility in creating universal health care, does not take this pessimistic viewpoint.

Applying a different metaphor, Yeh observes, "It's like starting a new neighborhood. It is impractical for the residents to wait for the supermarket to be built and the bank to open up before they move in. On the contrary, after people move in, stores and banks, seeing there is money to be made, will naturally follow."

Nevertheless, before a health care network is established, a number of apparatuses which should be implemented will unquestionably be obstructed. Not only will it be impossible to dismantle unreasonable temporary measures, but also the DOH will have to pay for inappropriate expenses. Will universal health insurance ultimately succeed in hastening the arrival of a perfect health care network, or will the present imperfect health care network drag down universal health insurance? This is a race against time. For the Department of Health and the entire citizenry, it will be a severe test.

[Picture Caption]

p.28

The Universal Health Insurance Plan, initiated in March of this year, will allow the nine million Taiwan residents who have not had access to health insurance to step out from under the shadow of "not being able to fall seriously ill." Currently the plan is the recipient of both praise and condemnation. No matter which view holds the most merit, universal health insurance has already become a milestone in Taiwan's health care system.

p.29

Universal health insurance benefits those who originally had no insurance, but the burden on those who already had insurance is correspondingly heavier. Of these, blue collar workers have protested the most loudly. The photo shows a workers' protest march.

p.31

Comprehensive Medical Care System

p.32

Limited in terms of transportation and population, remote mountain villages and offshore islands may not be able to support a professional physician. But with such means as mobile medical vehicles and telemedicine, which have been in operation for some years, most illnesses can be handled. (photo by Cheng Yuan-ching)

p.33

Regional Disparity of Physicians Before and After Implementation of Health Network Plan

Note: Target number for the second phase of the health care network is a minimum of 6.5 doctors per 10,000 people in every medical region.

p.33

Regional Disparity of Hospital Beds Before and After Implementation of Health Network Plan

1995 estimate includes those which were certified but not in operation as of June 1994

Note: Target number for the second phase of the health care network is a minimum of 20 ordinary hospital beds per 10,000 people in every medical region.

p.34

Outpatient Medical Costs Paid by Insurance Holders Under the Universal Health Insurance Plan

Source: National Health Insurance Bureau

p.35

The medical referral system, in which minor illnesses are treated at smaller clinics and major afflictions at large hospitals, is based on the best of intentions, and it can reduce the misuse of medical resources. On the one hand, it requires the cooperation of the people, but creating a good referral system is a pressing matter.

p.36

In the past small local hospitals had relatively few hospital beds and little economic prowess. In the future they may be able to go the route of group-practice clinics or chronic illness treatment centers, in order to use resources more rationally.

p.37

Health care places an emphasis on prevention. In terms of expensive major injuries, good public safety and emergency rescue operations can help reduce the number of accidental injuries, which can amount to a great savings in medical insurance costs. The photo shows the aftermath of the "Ode to Joy" KTV fire in Taipei.

p.38

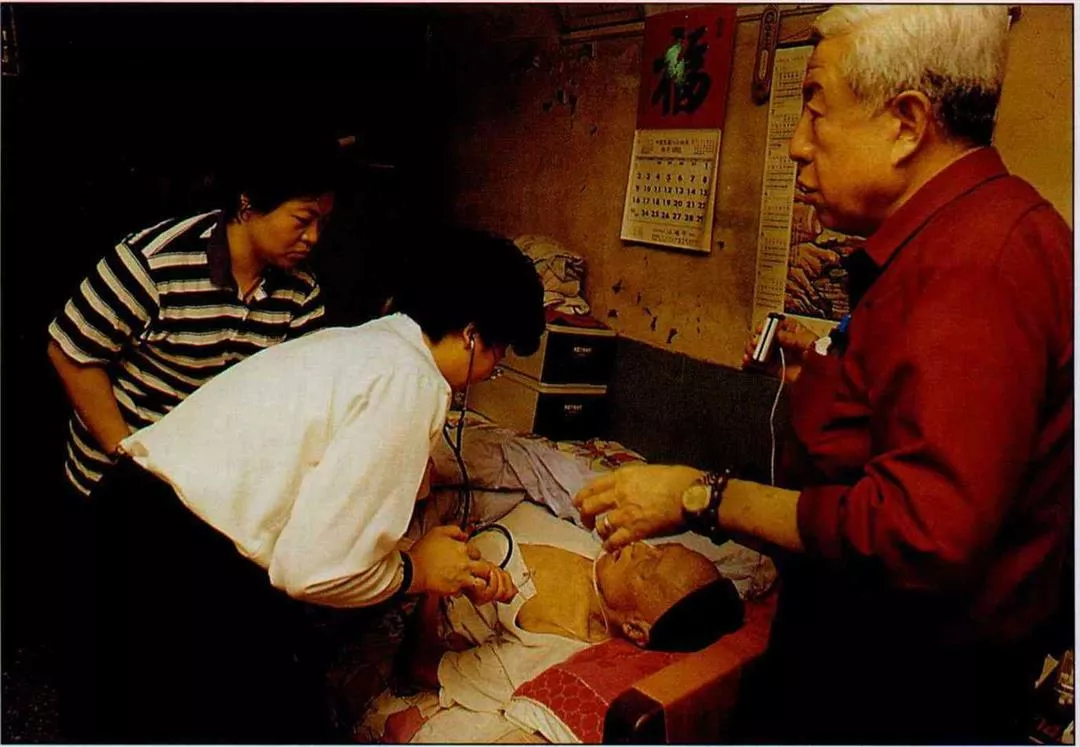

In the past, in-home nursing was only covered by public servants' insurance and operated at an experimental level. In the future, it will be covered in full under universal health insurance, to encourage patients bedridden for long periods of time to receive care in their own homes.

In the past, in-home nursing was only covered by public servants' insurance and operated at an experimental level. In the future, it will be covered in full under universal health insurance, to encourage patients bedridden for long periods of time to receive care in their own homes.