Hiram Fong's father, Lum Fong, born in Chungshan County, Kwangtung Province, came to the island of Maui at the age of fifteen to work as a contract laborer. The elder Fong's thinking was the same as that of other Chinese at the time: he only wanted to earn enough money to go back home, buy some land, and raise a family.

"That was the hope of all Chinese," Senator Fong explains. "Land here was a dollar an acre, but who wanted to buy land in a foreign country?"

His father worked hard and saved up several thousand dollars to return home in triumph. The fates, however, had other plans in store. After buying a ticket and reserving a place onboard, he lost nearly all his money in gambling. In the end he decided to stay where he was, to marry, and to settle down.

That decision changed his way of thinking, and it also produced the first Chinese-American U.S. senator.

Hiram Fong was born in 1906, the seventh of eleven children. It was common at the time for the children of disadvantaged families to work at odd jobs to supplement the family income. At the age of four, Hiram began earning a wage with his brothers and sisters picking algarroba beans for cattle feed. Later he shined shoes, sold newspapers, and caddied for 25 cents an hour. He worked in a pineapple processing plant when he was a little older.

After graduating from high school in 1924, Hiram Fong worked as a supply clerk at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, at the same time taking evening classes in Chinese at a school for overseas Chinese. After three years he had saved up enough money to attend the University of Hawaii, where he earned a B.A. in 1930. He then worked in the county department of water for two years, saving up money to attend Harvard Law School.

Why law? "I figured that as a lawyer I could be a good liaison between the Chinese community and the rest of the communities in Hawaii," he explains, revealing his early aspiration to serve the public.

Besides earning good grades, Hiram Fong revealed a quick mind and a talent for speaking even as a youngster. He has always believed that "people judge you on how well you speak," and in law school he seized every opportunity to take part in speeches and debates and refine his speaking techniques.

Stepping up to the podium is good practice for stepping onto the political stage. After seeing him in action, the Republican candidate for Honolulu chief of police, Patrick Gleason, took a liking to the precocious 22-year-old and asked him to work in his campaign. Gleason was elected.

Two years later, the same thing happened in the mayor's race: Fred Wright, the candidate he helped, was elected too.

In 1935 the 29-year-old Fong began working as a city and county deputy attorney. Three years later he was elected to the Hawaii Territorial Legislature. The same year he married his wife Ellyn, another second-generation Chinese-American.

Altogether he served sixteen years in the territorial legislature, the last six (l948 to 1954) as speaker of the house.

At the same time as he was speaking up for his constituency, he didn't forget to develop his own strengths and interests. He set up a law office to practice what he had learned in college and was also successful in finance, real estate, and construction.

In 1959 Hawaii became the 50th state of the union, and Hiram Fong, the 53-year-old son of a farm laborer, was elected to the U.S. Senate.

As the first person of Oriental ancestry to join the ranks of that institution, he had some doubts about how he would be treated. Those fears were quickly dispelled when he was warmly met at the airport by Vice President Nixon and U.S. Senators Barry Goldwater and Everett Dirksen.

Senator Fong won two major appropriations for his state during his first three years in office: US$500 million to build the first 30-mile stretch of the H-1 highway in Oahu and US$8 million to establish the East-West Center in Manoa. He continued to strive equally to advance the state's industry, agriculture, education, and tourism during his eighteen years and three terms in office.

Senator Fong was also responsible for several bills of great assistance to Asian immigrants: raising the quota on Asian immigrants from 105 a year to 20,000, demanding that the Immigration and Naturalization Service accept Cuban refugees of Chinese ancestry, nullifying the anti-Chinese exclusionary laws, and prohibiting racial discrimination in rental housing.

After leaving politics, Hiram Fong set off on a new career in business. The son of a contract laborer, he is now a multimillionaire who directs more than 400 employees in 24 different enterprises, including finance, investment, insurance, and law. The scope of operations covers the entire United States, even Alaska.

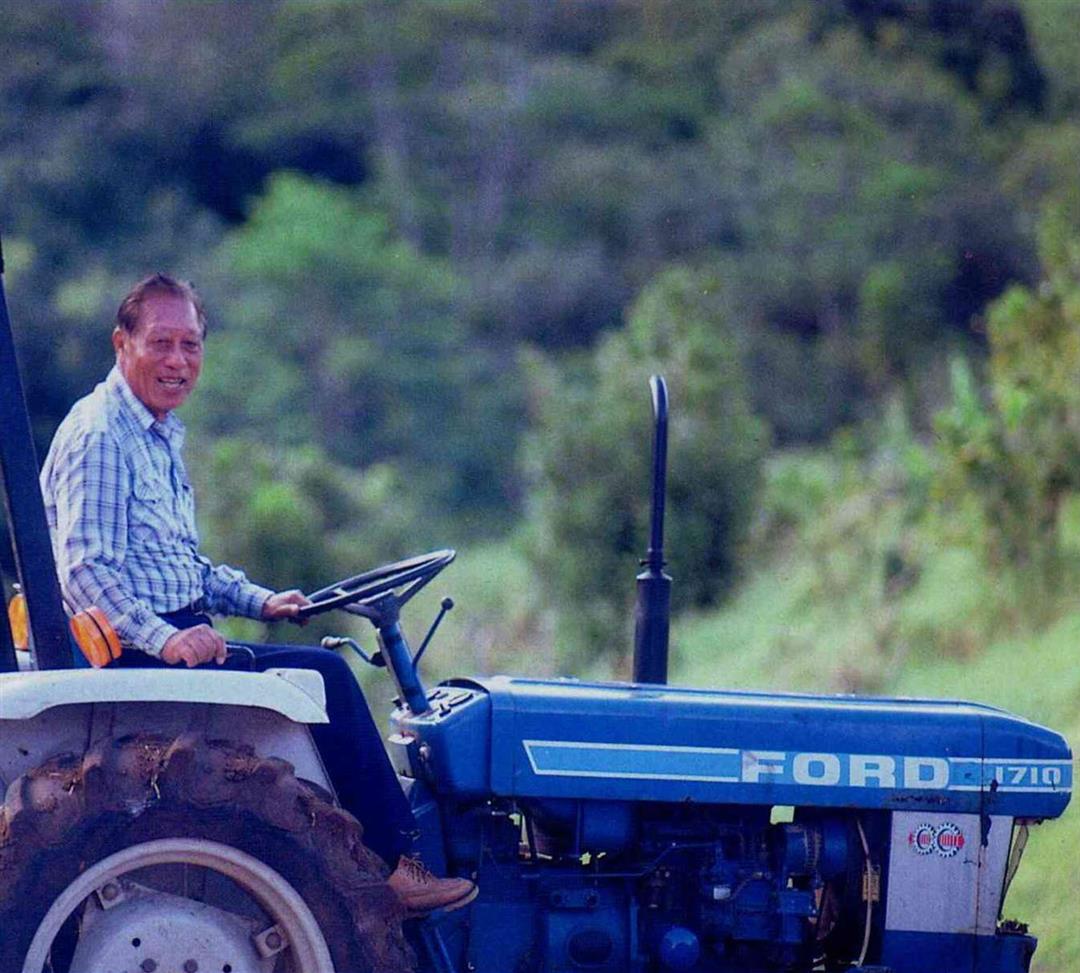

But like many Chinese, Fong has always had special feelings for the soil. In the morning he may sit in the CEO's chair, but in the afternoon he can often be found toiling away in the 725-acre gardens that he has gradually accumulated over the past several decades.

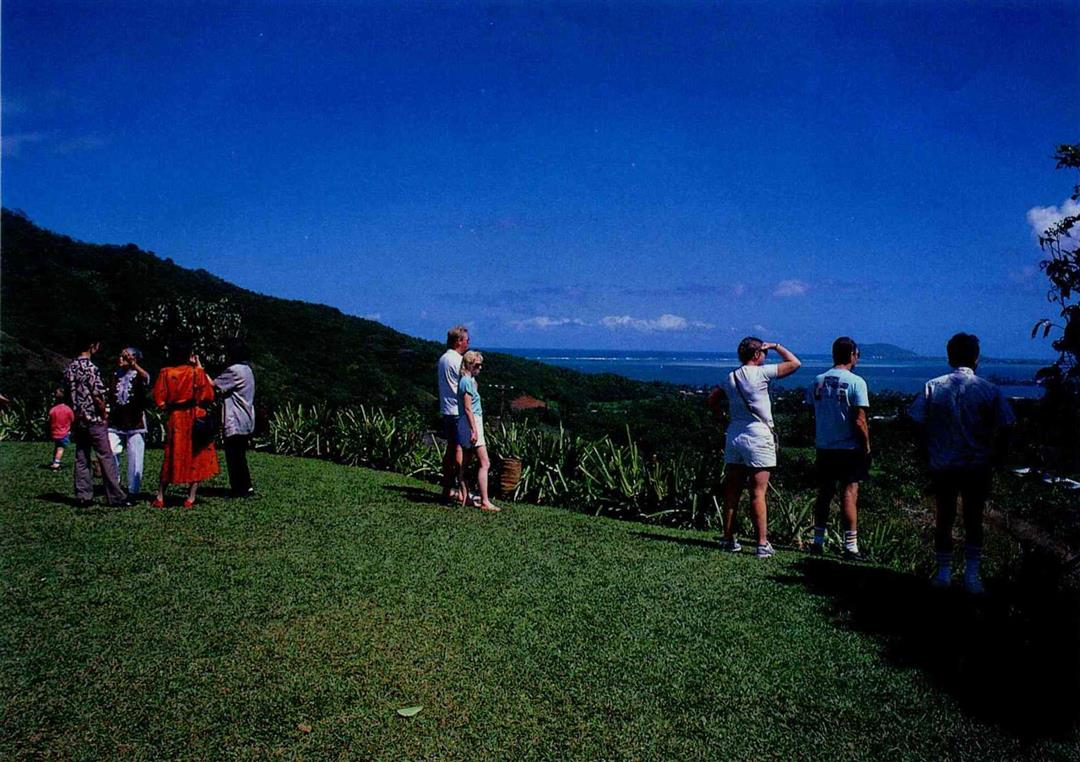

Opened to tourists, the gardens have a gift shop, restrooms, and a snack bar, and visitors can take a guided bus tour to learn more about the hundreds of plants and flowers there.

As a second-generation Chinese, Senator Fong has always encouraged people to preserve their cultures in a multifarious society.

For the celebrations commemorating the arrival of the first Chinese to Hawaii 200 years ago, he donated a 200-meter-long dragon and mobilized nearly a hundred of his employees to take part in the event. Striding through the sky to the sound of drums and gongs, the giant dragon was an affirmation of 200 years of labor and struggle by the Chinese immigrants to Hawaii and also a fitting symbol of Hiram Fong's personal success and achievement.

[Picture Caption]

Senator and Mrs. Fong embody the traditional Chinese love of the soil.

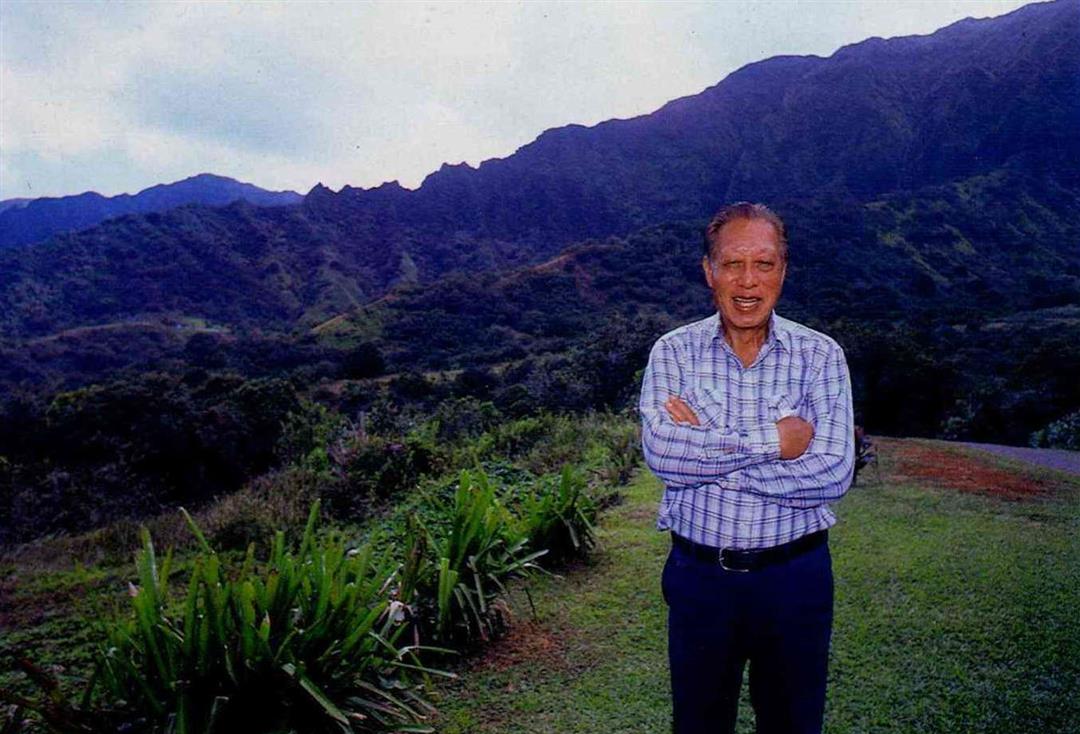

Senator Fong's gardens have expanded to a considerable scale over the years.

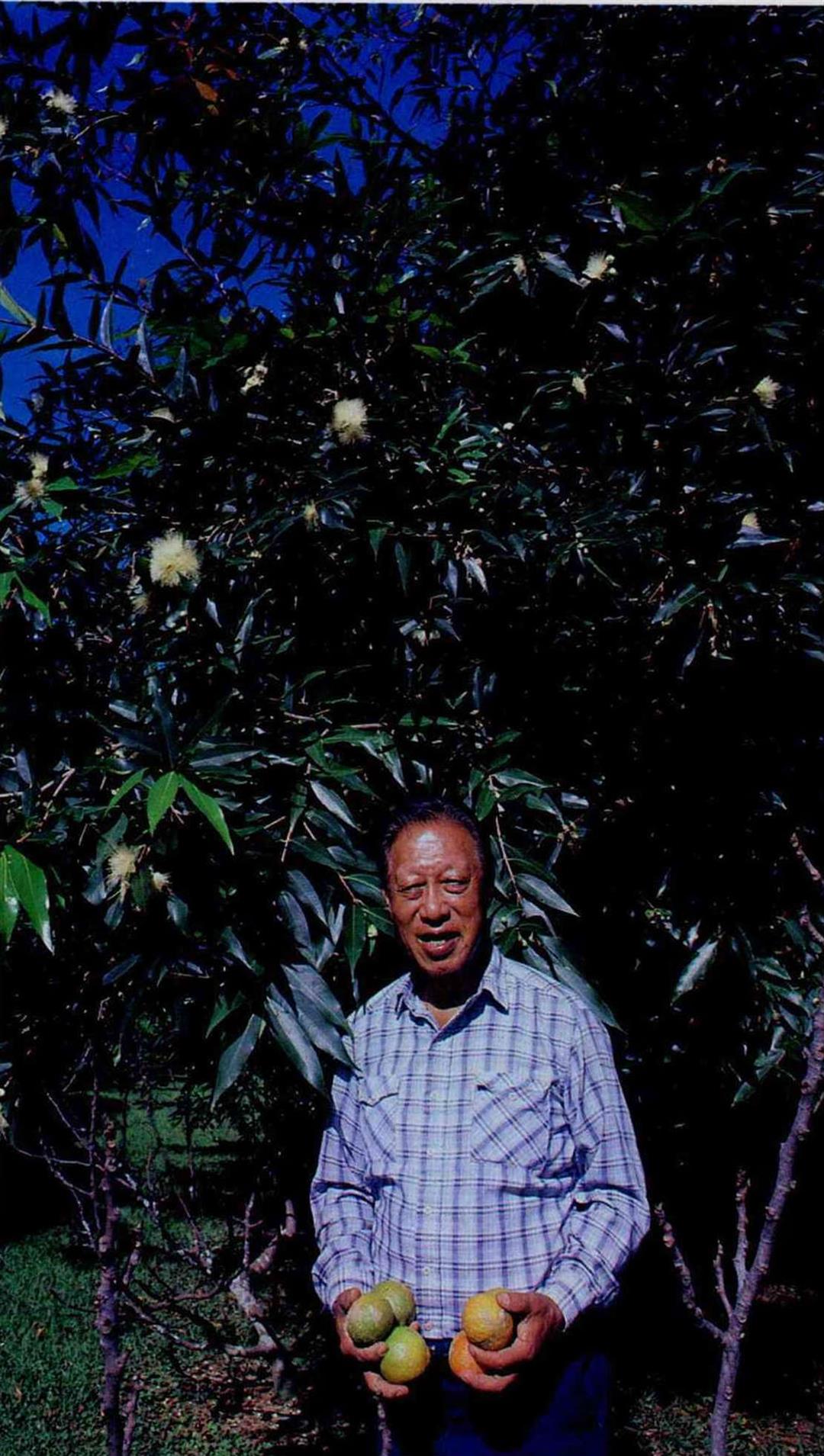

Many fruit trees in the gardens were brought to Hawaii by early Chinese immigrants and are not native to the islands.

(Above) A bird-of-paradise flower adds a touch of exuberance to the gard en greenery.

(Below) Japanese tourists are adept at weaving orchids from the garden i nto souvenir leis.

Senator Fong, who works in the gardens every day, believes that the exer cise is good for his spirits.

Visitors look out over a panoramic vista from a hilltop in the gardens.

Senator Fong's gardens stretch all the way to the first line of mountains in the distance.

Senator Fong's gardens have expanded to a considerable scale over the years.

Many fruit trees in the gardens were brought to Hawaii by early Chinese immigrants and are not native to the islands.

(Above) A bird-of-paradise flower adds a touch of exuberance to the gard en greenery.

(Below) Japanese tourists are adept at weaving orchids from the garden i nto souvenir leis.

Senator Fong, who works in the gardens every day, believes that the exer cise is good for his spirits.

Visitors look out over a panoramic vista from a hilltop in the gardens.

Senator Fong's gardens stretch all the way to the first line of mountains in the distance.