Sometimes known as "green gems" or "green diamonds," betel nuts have over the last 30 years been an economic miracle for Taiwan's agricultural villages. The betel-nut industry may have a terrible image and be subject to its own "three nos" policy-the government does not encourage, provide guidance for, or prohibit betel-nut growing-but it grows stronger by the day. Betel nuts themselves are now Taiwan's second-largest agricultural product, behind only rice. Betel-nut farmers, wholesalers, and retailers have developed an efficient production and distribution system for their product, one subject neither to the predatoriness nor to the booms and busts so common to other agricultural products.

However, the continuing degradation of Taiwan's natural environment, the growing frequency of droughts and floods, and the likelihood that our 2 million red-lipped betel-nut chewers will become victims of oral or liver cancer have given rise to endless calls for a government review of the betel-nut industry.

The betel-nut industry has deep roots in Taiwan, where hundreds of thousands of people depend upon it for their livelihood. Given that it will not be easy to root out, what should we do about it?

Pingtung kicks off Taiwan's six-month-long betel-nut harvest in May, when the fruit is in short supply throughout the island.

As the sun begins to rise on a Monday morning in early June, Tsai Jui-tang, a 43-year-old betel-nut grower and distributor from Neipu Township, Pingtung County, drives his wife to their distribution center. Yesterday's harvest of betel nuts is piled up inside the steel curtain doorway, still attached to branches. While his wife waits for neighbors to come help cut the betel nuts from the branches, Tsai and an employee drive out to the fields to harvest more.

A large, muscular man, Tsai nonetheless looks tiny striding through the betel-nut orchard. When his sharp eyes pick out a tree with ripe fruit, he extends his telescoping scythe and brings a bunch of betel nuts tumbling down with a single swipe. He catches the bunch, tosses it back to his assistant, then re-extends his scythe to go after another. Wielding the 13-meter, four-kilogram scythe nonstop, Tsai harvests an entire two-hectare orchard in an hour. After delivering the fruits of his labor to his distribution center, he sets off to harvest another of his orchards. With several hundred swipes of his telescoping scythe, Tsai manages to cover more than ten hectares in just one morning.

The use of large earthmovers to uproot forests and make room for betel nut has badly damaged the environment by increasing the risk of floods, depleting water resources, and altering forest microclimates.

A six-month battle

Tsai is a typical Neipu grower-distributor, farming about 20 hectares of land he owns or leases. While he's harvesting his betel nut, he employs eight or nine elderly workers in his distribution center. There, the seniors sit on low stools cutting betel nuts from branches. "They come here to earn a little extra cash to help out their grandchildren," explains Tsai. He says that each makes NT$500-600 per morning a couple days a week, earning a total of a few tens of thousands of NT dollars over a six-month period. The workers have a meal at noon, then go home. In the afternoons, Tsai and his wife sort 100-200,000 betel nuts, including those they've harvested themselves and those that other growers have delivered to them, into nine grades. But before placing the drupes into the sorter, they must remove the bad ones-the unfertilized "oysters" and the pointed "sharpies" that have an unpleasant texture-by hand. They examine them basket by basket, pouring the green drupes onto a specially designed table, stirring them, then plucking out the bad ones with amazing speed and accuracy.

After a few hours of grading, brokers begin arriving to pick up their orders. Lai Ming-hsing, a broker from Tainan, arrives in a refrigerated truck and carts off nearly 20,000 betel nuts. When the kids get home from school in the evening, they join the production line, packing up orders for brokers from the north and the outlying islands, then notifying a package delivery service to come pick them up. The family's workday finally finishes at about ten in the evening.

"Betel nuts have to be shipped fresh, so you have to process them the same day," says Tsai. "Our volume right now is only about one-fifth that of the high season. When it picks up, we'll have to hire more people and will still end up working until one or two in the morning." Tsai explains that even though Pingtung's hot climate enables the trees to produce seven or eight crops a year, they only harvest three of them. The reason is that as the temperatures rise in the southern summer, the betel nuts ripen more rapidly. Those that ripen too quickly become fibrous, making them less pleasantly crispy than betel nuts from Chiayi or Nantou. Pingtung therefore stops producing in October, when Chiayi and Nantou begin to harvest in volume. "We have to work a little harder because we have to live for a year on what we produce in six months."

There are more than 1,000 distributors like Tsai in Pingtung County. The county produces betel nut in every one of its 33 townships. Given that its more than 40,000 growers have been generating annual revenues of more than NT$6 billion from the crop in recent years, it's fair to say that betel nut is the lifeblood of Pingtung's agricultural industry. "It's betel nut that sends the children of Pingtung's Hakka to university, then abroad to graduate school," says Mrs. Tsai. Betel nut also dominates the agricultural industries of Nantou and Chiayi, which, together with Pingtung, produce 75% of Taiwan's crop.

value poses a dilemma for government policy.

Good for the economy

Betel nut is grown all over Taiwan, not just in these three counties. But differences in climate mean that production periods vary with region. The production season kicks off in Pingtung in May and June, then begins moving north. It reaches Kaohsiung in July, Chiayi and Nantou in August, and Hualien in September, then moves into the north and the mountainous areas of central and southern Taiwan. The year's production cycle finally wraps up in April. The variability of supplies across the year creates a huge price differential between the high season and the spring low season. Betel nut is in short supply in April and early May, which causes prices to soar before they begin to inch back down in July.

A 1996 study by Huang Wan-tran, an expert in agricultural economics at Changhua's Chung Chou Institute of Technology, showed that Pingtung's growers were Taiwan's most profitable, raking in NT$450,000 per hectare (including wages paid to family members) at the height of the betel-nut craze. Even Kaohsiung's growers, who did the least well, generated revenues of more than NT$300,000 per hectare in those days. Huang's study also revealed that betel-nut growers enjoyed a revenue-to-expense ratio of 2:1 to 3:1. That is, for every dollar they spent on costs, they generated two to three dollars in revenues, yielding gross margins of 100-200%. When you consider that the ratios for rice, mangos, bananas, and pineapples were in the 0.8-1.8 range, growing betel nut was a very attractive proposition.

The story of betel nut

High revenues and high profits drove a massive expansion of betel-nut cultivation.

According to the Council of Agriculture, the number of betel palms planted in Taiwan began to increase continuously from around 1980. Over a 20-year period, the area under cultivation grew from under 2,000 hectares to a peak of 56,000 hectares in 1996. Meanwhile, annual production climbed from 16,000 tons to 160,000 tons, and production value soared from around NT$100 million to more than NT$13 billion.

"We used to say that betel nut was something 'a pig wouldn't eat and a dog wouldn't chew,'" says Yeh Wen-cheng, who has been in the betel-nut business for 30 years and is Neipu's main distributor. Yeh says that the manufacturing and long-distance transportation industries boomed when Taiwan's economy took off in the 1980s, and many of those employed in those fields began chewing betel nut to boost their energy levels and stave off the cold. From there, betel nut evolved into a part of the business culture as something to be shared while negotiating. Yeh still vividly recalls betel nut hitting a price of four for NT$100 in 1983. "In those days, the South's shipbreaking industry was making money hand over fist. When owners went out of the office, they always had a pack of betel nut on them. Offering to share betel nut with their clients showed that the bosses thought them important." In spite of the high demand, supply was still limited, causing prices to rise across the board. Betel nut isn't a difficult crop to produce. As long as farmers monitor their trees closely, they earn good returns. As a result, even small farmers with little capital began planting betel nut to supplement their incomes.

The betel-nut industry's well-developed production and distribution system enables farmers to earn good, steady incomes from it.

Huang says that during the May to September period in which Pingtung leads the island in production, local brokers function as price leaders. From October to March, Chiayi's brokers take over this function. In both places, wholesale prices are set by groups or alliances of distributors in meetings or on the phone on the night before shipment days.

"Prices have to be set at a level that allows growers and sellers to profit," says Huang. "When production is high and sales low, weak producers are driven out of the market." Huang says that the distributors base their prices on retailers' prices. Usually they estimate what volume will be in the current market before they harvest, then look at how much retailers are selling around the island. They then find an equilibrium and establish their price.

Clippers click in the morning air as these elderly women remove betel nuts from their branches. In the afternoon, the bad drupes will be removed, and the good ones graded and weighed. In the evening, brokers will arrive to purchase their goods.... The same scenes play out all across Pingtung every June.

A model distribution system

"We have to respect the vision of the older generation of distributors," says Tsai. He explains that in the old days, prices were usually set by the elders in the distributors' groups. In the interests of fairness and providing stability to the market, they kept their profits low. Generally, when prices were above NT$2 per drupe, they limited their cut to NT$0.3; when they were below NT$2, they took NT$0.2. By keeping their margins low (at around 10%), they discouraged other distributors from trying to undercut prices and avoided the kind of market turmoil brought on by efforts to grab market share.

"The older generation believed that by taking a little less for themselves, they could keep the market stable and ensure that everybody made money," says Tsai. He adds that in recent years criminal gangs have begun seeking to claim some of the betel nut's profits for themselves, and have used their control over the transportation system to attempt to influence market prices. However, the betel nut's low barriers to entry and very large number of players have made it a very difficult market to corner. As a result, the criminals have so far created only a small stir in a market that remains largely very stable.

In the mid-to-late 1980s, betel-nut cultivation began to supplant that of rice in Pingtung, and of bananas and bamboo shoots in Chiayi and Nantou. "Green gold" cultivation spread even to slopelands and leased sections of national forest. By the time betel-nut acreage peaked in 1996, the general public was appalled by the industry's use of earth-moving equipment to uproot slopeland forests and orchards to make room for its crop.

Clippers click in the morning air as these elderly women remove betel nuts from their branches. In the afternoon, the bad drupes will be removed, and the good ones graded and weighed. In the evening, brokers will arrive to purchase their goods.... The same scenes play out all across Pingtung every June.

Water resource assassin

Chen Hsin-hsiung, a professor with National Taiwan University's School of Forestry and Resource Conservation, estimates that Taiwan grows 70% of its betel-nut crop on slopeland, versus only 30% on the plains. Though cultivation in the plains negatively affects the recharging of groundwater supplies, it does minimal ecological harm. That is anything but the case with large slopeland orchards, which are extremely detrimental to flood-control and water-conservation efforts, affect forest microclimates, and increase the frequency of droughts and floods. In 1994, Chen suggested that betel nut was killing the nation, and vigorously urged the government to take note of the damage that betel-nut cultivation was doing to the island's slopeland ecology and environment.

Chen explains that unlike the trees, bushes, and groundcover of the forest, betel-nut orchards don't absorb and retain rainfall. And since betel-nut trees are palms with V-shaped fronds, they route rainfall straight to the ground, creating ablation channels. Their negative impact on flood control efforts is worsened further by their root systems, which have a relatively loose grip on the earth.

Unable to hold rainwater in the soil, betel palms cause the water table to fall. Worse, because betel-nut orchards lack the cover of multistoried forests, they increase evaporation by allowing the sun to shine directly on the forest floor. The irrigation required by the palms in their growth phase also uses up significant volumes of water directly. "A hectare of betel nut uses as much as 100,000 metric tons of water per year, or about five times the amount that rice does," says Chen. Taiwan's 50,000 hectares of betel nut therefore use upwards of 5 billion tons of water per year-as much as Taiwan's annual industrial and residential water use combined.

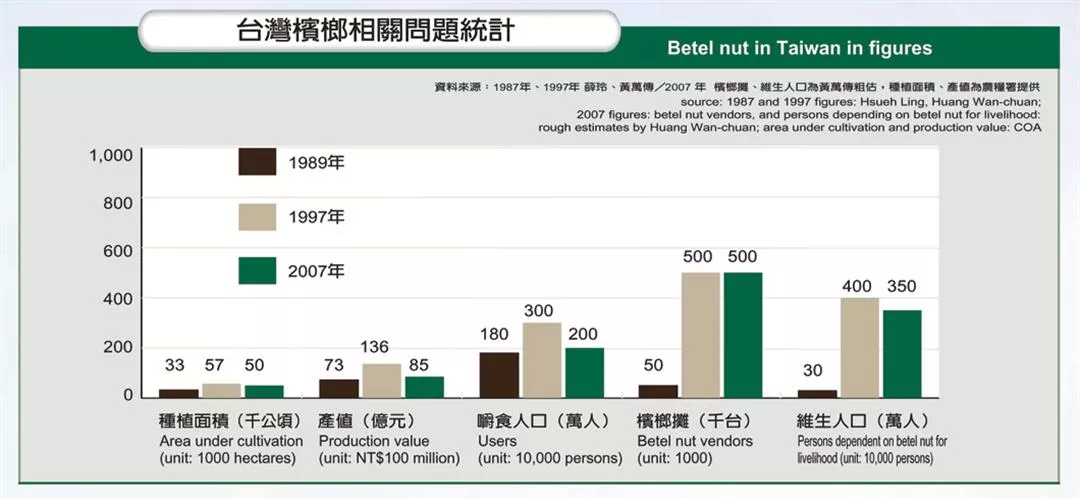

Betel nut in Taiwan in figures

Libeling betel nut?

Typhoon Herb struck Taiwan in 1996, causing massive landslide damage at the peak of the betel-nut growing craze. In the years following, Typhoons Toraji, Nari, and Mindulle triggered still more landslides, washing out bridges and roads, and causing many casualties. After each disaster, betel nut was named the principle culprit with blame ascribed to the cultivation of sensitive slopelands. After 2001's Typhoon Toraji, then-premier Chang Chun-hsiung declared that the government would remove all of Taiwan's illegal betel-nut orchards. To date, this policy has resulted in the reforestation of more than 8,000 hectares of national forest.

Nonetheless, farmers, scholars, experts and politicians have objected to the blaming of betel nut for the death and destruction of the landslides.

"Slopeland clearance for growing vegetables and building hostels is more to blame [than betel nut]," says legislator Tsai Huang-lang. "The main reasons for the problem are 700-millimeter typhoon rainfalls on top of earth loosened by the Chi Chi earthquake." Tsai says that the number of dangerous creeks in Nantou County exploded from something over 200 before the 1999 earthquake to more than 400 after, and argues that all it takes to trigger a landslide is a heavy rain. Yet, says Tsai, the government is libeling betel nut by pinning the blame on its cultivation, and wonders how farmers are supposed to make a living if the palms are all cut down.

Paul Lee, a professor in the department of soil and water conservation at National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, similarly states that equating betel-nut cultivation with landslides is an example of "the media misleading the public." According to Lee, landslides require three fundamental conditions: a mass of earth, a large amount of rainfall, and a sufficiently steep slope in a riverbed (at least 15-30o). Geology, hydrological factors, and soil density also play a role. Given the complexity of the factors that give rise to landslides, he feels that it is unfair to simply attribute them to betel-nut cultivation.

The harvest season may mean long hours, but the bounty of this grower's betel-nut crop has brought a smile to his face.

Closing the barn door

Besides coming to the betel nut's defense in this way, the scholarly community has further advice to offer.

Chen says that if farmers can plant betel palms in bands with other trees, they'll slow their water consumption, mitigate their effects on the microclimate, and reduce the kinds of pest problems associated with monocropping. Such a practice would protect both the environment and farmers' livelihoods.

Lee recommends employing natural succession to restore forests-first thinning the betel-nut orchards, then planting species with a high economic value (such as teak) or fast-growing trees that can be turned into paper pulp. Farmers wouldn't cut down their betel-nut trees until their new crops could be harvested. He argues that clearcutting large swaths of land would leave the topsoil exposed while the new trees were growing, negatively affecting soil and water conservation efforts.

But, with the exception of its ban on illegal growing, the government's betel-nut policy has so far failed to move beyond the kind of passive responses embodied in the "three nos."

According to the Council of Agriculture, the government has now restored the majority of the 8,000 hectares of leased national forest land that had been used for illegal betel-nut cultivation, and the Forestry Bureau's monitoring efforts have been pretty effective. Meanwhile, of the more than 10,000 hectares of land at slopes greater than 28o that were illegally planted with betel palms, some 5,000 hectares have been turned over to cash crops such as bamboo and plum. Another government effort initiated at the beginning of this year has formally placed under agricultural oversight the 30,000 hectares of legal betel-nut orchards located on the plains and on slopeland approved for agricultural uses. The government has also created incentive programs aimed at transferring these plots to other uses and restoring forests on the plains. Intended to reduce the acreage used to cultivate betel nuts, the incentive programs have so far been ineffective, suggesting the need for stronger incentives and better guidance.

Geologically speaking, Taiwan is relatively young and fragile. Forests are our only means of preventing droughts, floods, and landslides. This makes the question of how to balance environmental protection and agricultural economics an important one for us all. The photo shows a hilltop betel palm plantation in Nantou.

Natural obsolescence

"The government wants to use market mechanisms to create a natural contraction in the industry," says Hsu Han-chin, chief secretary of the Agriculture and Food Agency, explaining that the government has only limited resources with which to oversee many industries. But, if the subsidies given to encourage the transition to other crops are too large, idle acreage will explode and the price of betel nut will skyrocket. That, in turn, will draw more people into betel-nut cultivation. He believes the best way to approach the problem is from the demand side, shrinking the industry by reducing the number of betel-nut chewers.

Industry figures with their fingers on the pulse of the market have already noticed a slowdown. Pingtung betel nut farmer and distributor Tsai Jui-tang, for one, is planning a transition to other crops. He believes that the decline in the number of users, brought on by the government's cancer prevention efforts, and the importation (legal and otherwise) of betel nut from Thailand and mainland China have brought down prices and made it harder to do business. Tsai has been growing bananas for a number of years, and is now also looking into the feasibility of producing flowers.

"I don't know what I'd do without betel nut," says Chu Chung-tao, a betel-nut and mango grower. Though Pingtung is famous for its Irwin mangoes, those grown in Neipu lack the bright color and flavor expected of the variety. Wax apples are a poor alternative because farmers lose money on them as often as they make it. Rice is even worse-growers break their backs year round, but earn hardly anything.

Will betel-nut chewers decline in number until they eventually disappear altogether? Sociologists tell us that years of effort by health departments have made the public well aware that chewing leads to oral cancer. But 1-2 million Taiwanese still have the habit for reasons related to social structure. Young people chew it seeking recognition from their peers. Working people chew it to fit in on the job or in social settings. Laborers use it for an energy boost. And many people use it just as they do cigarettes and alcohol: to relax or relieve stress.

"Betel-nut chewing is more than simply a personal addiction," says Kuo Shu-chen, an assistant professor in the Department of Healthcare Management at Yuanpei University. "It is instead a component of various settings and various social interactions in everyday life."

Understood in this way, it appears that the decline in betel nut use that the government is aiming for and the farmers fear is unlikely in the near term. And, if there's a market, there will be producers. Is this good for farmers? Bad for the environment? A problem for consumers? How are we to decide whose interests take precedence? This is a genuinely difficult question. We need more people to weigh in if we are to find an appropriate solution to the problem.

Clippers click in the morning air as these elderly women remove betel nuts from their branches. In the afternoon, the bad drupes will be removed, and the good ones graded and weighed. In the evening, brokers will arrive to purchase their goods.... The same scenes play out all across Pingtung every June.

Clippers click in the morning air as these elderly women remove betel nuts from their branches. In the afternoon, the bad drupes will be removed, and the good ones graded and weighed. In the evening, brokers will arrive to purchase their goods.... The same scenes play out all across Pingtung every June.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)