Looking Back Over 20 Years of ITRI

Laura Li / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Christopher Hughes

July 1993

"I work at the Industrial Technology Research Institute." "Oh, is it the National Taiwan Institute of Technology on Keelung Road? Aren't there always traffic jams there?"

Since the Industrial Technology Research Institute became confused with the National Taiwan Institute of Technology, there have been perhaps more than a few people who have never heard its real name. Regrettably, this gathering of more than 400 holders of doctorates in science and engineering and some 5000 employees who have had such an impact on Taiwan's 80,000 manufacturers, has only come to prominence with the battle over the swinging budget cuts made by the Legislative Yuan.

Twenty years old this July, it seems that the ITRI is now at a crucial turning point concerning how to fix its status.

As far as the ITRI is concerned, May was a month full of setbacks.

This was because when the Legislative Yuan was scrutinizing the budget put forward by the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOFA), legislators wanted to cut NT$2 billion from its science and technology budget, of which NT$1.3 billion was supposed to be set aside for research and development to be conducted by the ITRI. Such a contraction in the budget of its biggest customer would naturally influence the income of the institute.

What was hard to bear, though, was that when news of the budget cuts broke, not only was there little support from business circles to be seen in the press coverage, but there were even many people who aired criticisms of the ITRI, such as that its efficiency was not evident, its interests conflicted with those of the private sector, its status was uncertain, and so on. Usually a place where people's heads are buried in their books, the research institute was suddenly thrown into a state of confusion. One researcher dejectedly expressed the feelings of many of the ITRI's researchers when he remarked, "I had always thought that working in the institute was something to be proud of, a contribution to the nation's industry, but now I know this is what other people really think of us."

In actual fact, the "other people" are not that many in number. The silent majority of industrialists confirm the 20 years of contributions made by the ITRI. Li Ying-tsai, assistant manager of Mitac International Corp., when talking about the institute says it has been done an injustice. It is his opinion that the ITRI has been like a lighthouse leading the way on the road of Taiwan's industrial development. J.S. Ku, president of Alona, Taiwan's biggest producer of vending machines, which once commissioned the ITRI to undertake joint research and development, points out that if manufacturers just have the ambition and understand how to "dig up treasure," then the institute is in fact a very good place to use.

There are many employees who commute daily from Taipei to Chutung, and they don't want to waste the time they spend in transit.

Old name--new problems:

Practicality and ease of use were the original aims of establishing the ITRI. Taiwan's medium and small enterprises are many, yet with few personnel and not a lot of money behind them they lack the power to under take research and development for themselves. Thus the government could only use the strength of the state to establish the ITRI, hoping that it would become the common backup and technical support unit for all manufacturing industry. This general aim has not changed over 20 years. What has changed is the overall environment and structure of manufacturing. The old name and form of the ITRI, when confronted with these great changes, could not avoid often being landed in a jam and being faced with dilemmas.

The most serious argument at the moment concerns the problem of how the technology of the ITRI is set apart from industry. Wang Tzay-chyuan, manager of the institute's technical diffusion department, points out that ten years ago the scale of Taiwan's manufacturers was generally very small, with most of them only knowing how to follow the beaten path. Sometimes foreign customers would come up with product specifications that they wanted manufacturers to produce, but even if businesses could only get hold of the technology they wouldn't know how to use it. Because of this, the ITRI had to help them research and develop complete products, often helping them with even the equipment (often the businesses were not able to buy it, or could not find it) and the manufacturing process to begin production.

Up until today there are still countless small manufacturers who naturally need the institute's careful fostering from start to finish. On the other hand, there are some industries, especially the electronics companies which have developed so rapidly in recent years with the support of the institute, where many manufacturers have reached such a size that they are able to do their own research and development and have the ability to come up with their own products. They can even compete in some areas with the ITRI. The demands that they make on the institute are naturally different from those of other manufacturers. Lin Min-shyong, general director of the institute's Opto-Electronics & Systems Laboratories, says that leading-edge core research and development upsets small businesses, while practical product development upsets the large ones, so it becomes really very hard to satisfy everybody.

Liquid crystal display (LCD) technology is an example. Hsing Chih-tien, head of the institute's Electronics Research & Service Organization, points out that at present the whole industry recognizes that LCD is one of the most important products following on from integrated circuits (IC). Manufacturers the world over are actively trying to get a look in on the leading edge to avoid going under in future. Large domestic manufacturers, such as Lienhua Electronics, already have the ability to make a kind of LCD display, which makes them unwilling to see the ITRI use the strength of the state to come into the private sector and undertake research and development. The ITRI might even come up with its own prototype, which under the principle of openness will be transferred to the manufacturing arena and create competition, thus coming into conflict with private companies.

Manufacturers talk business for business's sake, and one can't blame them for trying to get as many benefits as possible. Meanwhile, "The ITRI is like a brigade that has been assigned to take a mountain, responsible for leading the way and testing the waters. But among our members are those who are faster of foot, lacking in patience and are unwilling to submit. The weak stragglers are worried, however, that we are moving too fast and have given them up for lost," says Otto C.C. Lin, with some exasperation. Unfortunately, the government's stand is to support the whole LCD industry, and it put ITRI in charge of research and development in the field. Ten years ago, for example, when the institute's electronics laboratory led the way in establishing Taiwan's IC industry, and successfully helped in the same way as did the industrial parks. A pluralistic society has a plurality of needs, and the institute is stuck in the middle without being its own master and not being able to please anybody.

ITRI is not only the acronym for the Industrial Technology Research Institute; if you tack on a "DE," you get the initials of the six major concepts that drive it--innovation, teamwork, respect, industriousness, dedication, and excellence.

National resources--needs must be satisfied:

At present the special technology projects commissioned to the ITRI by the MOEA number around 40, which is an indication of the institute's research and development strength. In principle, this research and development is public property and all taxpayers have a right to use it. Yet just where the line should be drawn here is another one of the institute's dilemmas. "Why do you give it to him and not to me?" "If you gave it to me, why did you give it to him too?" "Why do you do what he needs, and not what I need?" Such disputes are interminable, and with every argument the relationship of trust within industry and between industry and the ITRI is damaged.

Executive vice-president of ITRI Chintay Shih points out that it is precisely because the technological resources used by the institute can become saleable commodities that the crucial problem arises of how to coordinate their fair distribution. From the point of view of the ITRI being public property, its research and development can naturally be used by anybody. This is the position that is at present fixed by the institute's founding regulations. But it is retorted that in the hornets' nest of industry, with its chaotic cutthroat pricing and customary disunity, the result of three monks struggling over a drink of water is that nobody gets any water to drink.

There are just too many cases to cite. For example, three years ago the institute's Computer and Communication Research Laboratories brought together manufacturers to jointly develop a notebook computer. As soon as the news got round, there were 46 manufacturers taking part, among whom were a number who had never before had anything to do with computers. Not being able to turn away anyone who happened to come along, and with each company only having to cough up around NT$1.2 million, the consequence was that at an international computer exhibition all the manufacturers from Taiwan had notebook computers based on the same prototype developed by the institute. The result was price slashing and chaos in the world market. Those manufacturers who had a real interest in doing quality research indignantly withdrew.

The present way in which the institute goes about its work has already undergone some changes. If manufacturers want to participate in specialized research and development they now have to come up with comparatively higher matching funds, while restrictive technical specifications are stipulated to filter out freeloaders. The institute also has many views on how the results of its work are to be transferred. They hope, for example, that there can be prior assessment of factors such as market size for certain technologies, how many manufacturers can be sustained, and how much each one should contribute to ensure that the government gets a reasonable return on its research and development budget. Moreover, although the patents on research and development are public property, there might be ways to ensure that manufacturers can have a fixed period of exclusive right on their use. Only in this way can manufacturers be given a basic market guarantee.

Although there are many ideas, because the responsibility of the institute is to carry out research and development for its commissioning boss--such as the MOEA and other government units--the guaranteeing of patents on research and development, and even income from technology transfers, will mean handing over everything to the national treasury. Thus the right to decide just how its farcical regulations are to be changed is not in the hands of the institute itself.

Although they call themselves a "scientific oddity," the variety of skills among the ITRI staff is a spur to creativity.

A backup unit goes on the offensive:

There is also a daily increase in the number of large companies with international ambitions, which have their own variety of channels for bringing in technology. All do their own sums and the ITRI is just one among many choices, and it cannot avoid being secretly undercut at times. Again, the examples are too numerous to recall. The source of domestic air conditioning compressors, for example, has always been controlled by Japanese hands. When at one time domestic enterprises made considerable distribution inroads, the Japanese got jealous and reacted by cutting the supplies and raising prices while vexed manufacturers could only look on with exasperation as their orders piled up. After many such lessons, domestic manufacturers all want to bring in technology and produce it for themselves, yet there is still no channel by which to do this. There is no way the Japanese can lightly transfer the technology for such important components while the domestic businessmen have to worry about the domestic market being too small and their own production not being economically efficient.

In this situation the government decided to set up a special project, enlisting the ITRI's Mechanical Industry Research Laboratories to bring in American technology for combined research and development. When the development was finished, hands were joined again with the private sector to establish a compressor factory, with joint production and distribution free of Japanese control.

The strategy looked to be quite good and it was carried out very smoothly. Yet it was just then that the big Japanese compressor manufacturer, Toshiba, announced it was going to cooperate with the domestic TECO Electric & Machinery company and a Taiwanese fluorescent lamp company to establish a large-scale compressor factory in Taiwan. When the news broke, the participants in the special project could not help feeling rather flabbergasted. At present the compressor company supported by the institute is still being initiated according to plan, yet with such a strong enemy it faces a bitter fight ahead.

"Although not quite as planned, could the institute's project be considered a success? Of course, the ball is still in the air. But at least the institute did prove its own research and development ability and put out the message that if foreign manufacturers will not transfer technology, then the ITRI has its own way to produce it," points out Shih Yen hsiang, director general of the Medium and Small Business Administration of the MOEA.

Looking at it from a certain angle, domestic manufacturers are not united. Originally it was only the ITRI which stood behind and supported everybody, at times not only devising strategies in the command tent and supplying foot soldiers, but even falling into the enemy ranks and expending a lot of their own energy without reaping any of the profits. On the other hand, the private sector also feels that so as to find alternative channels early on for procuring technology and properly putting it into manufacturing, they do not want to operate under the direction of the institute and share technology and the market with other enterprises. The institute itself cannot wait for private sector achievements and rashly jumps in, and has to put up with the bad name of coming into conflict with the private sector. It is in this way that the interests of individual manufacturers come to collide with the interests of manufacturing as a whole, often leaving the ITRI, which is disinterested so far as its own profits are concerned, stuck in the middle in a rather embarrassing situation.

Quiet and even a bit uninspired, the main area of the Institute rarely sees people strolling about; everybody has their heads buried in their respective labs.

Encouraging manufacturers to form their own networks:

What ultimately is the safe distance that must be preserved between the research and development of the ITRI and industry? C. Richard Liu, general director of the Mechanical Industry Research Laboratories at the ITRI describes it in terms of "close is a worry, far is also a worry." Go too far ahead and the technological standards of industry will not be able to cope with it, and the market will not even be formed yet. Everyone will lack interest, and ITRI will be said to have bitten off more than it could chew and if you get too close, then you come into conflict with the private sector. If you do not go along with things, but private enterprises want something that the institute has not done, then this will also bring criticism. Timing and the choice of direction for research and development are not things that only depend on the wisdom of policy makers. At times they are really just as much a matter of luck.

C. Richard Liu points out that the rate of use of patents on research and development held by institutions in countries all over the world is generally not very high, with much effort having been expended on patents that lack any appeal. And it is just because the risks of research and development are so high that the amount of investment put into it by domestic manufacturers is only about.68 percent of their annual income. Many manufacturers do have complications, though; no matter whether they want to know why they themselves have had to withdraw goods from distribution, or whether a particular important component is temporarily in short supply, all look to the institute for help. Just as when the "teaching hospital" becomes the "casualty ward," at times you just do not know whether to laugh or cry.

There are also many entrepreneurs who say that, although the ITRI was established to support small and medium businesses, they want to have some slow growth for themselves. The job of the institute was always to give entrepreneurs some "fish" to eat. But now, apart from this responsibility, the institute should also be encouraging the idea of businesses establishing their own networks, or should be raising up partners who could teach them how to catch their own fish. But this would again leave the institute faced with a dilemma over its functional position and role.

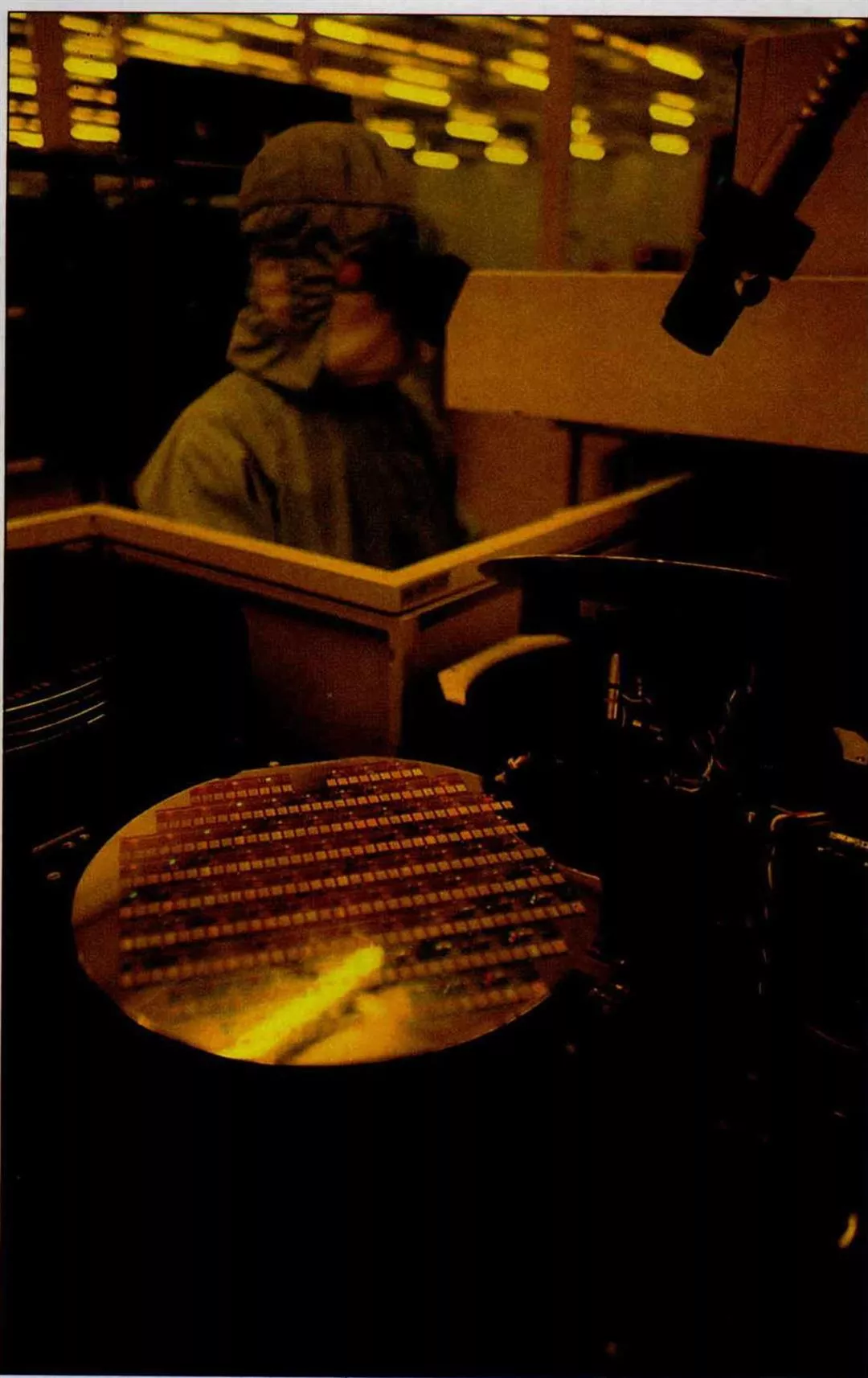

The newly-completed national-level "submicron lab" is the first demonstration factory in the country for wafer integrated circuits. Given the requirement of a "dust-free environment," workers can only go in "fully protected.".

The future not in its own hands?

C. Richard Liu takes the example of the service for automation of production that has been promoted by the institute's Mechanical Industry Research Laboratories for many years now. Taiwan basically did not have any intermediary companies providing this kind of service in the past, and the MIRL could only take on the responsibility of giving direct guidance to all kinds of enterprises and industries. Yet with there being some 80,000 manufacturing enterprises in the country, no matter how much the MIRL went all out, each year it could serve several hundred companies, not even one percent of the total. Now the MIRL has changed to mainly guiding intermediary companies, making them into seeds and teaching resources in the hope that they will become effective levers saving the MIRL own more power for more difficult and challenging objectives.

However, it can also be said that although the conditions for each laboratory are different, on the whole much of the institute's income has come from providing this kind of industrial service. It makes good use of the institute's personnel, and they can also enjoy the direct gratitude of enterprises. Now with intermediary companies coming in to share these tasks, the institute is creating its own competitors, making employees inevitably skeptical about this kind of project.

"If the current services are gradually transferred out, and MIRL has no way to upgrade its own research and development abilities, this will create a sense of uncertainty about the future among the more than 1000 employees," admits C. Richard Liu. Being confined to research and development and providing services for the public interest without pursuing profits or conflicting with the interests of the private sector, the institute has to work toward the goal of being self-supporting and responsible for its own profits and losses. At the same time it has to avoid cuts in the work force affecting the work of research and development through eroding staff morale along with the demands of a host of other contradictions. The anxiety of the workers is not hard to understand.

Facing the shifting scenes of the industrial environment and in anticipation of the numerous quarrels between the institute and many who are outside it, on its twentieth birthday the ITRI deserves not only deep consideration--it even more so re quires encouragement.

[Picture Caption]

p.96

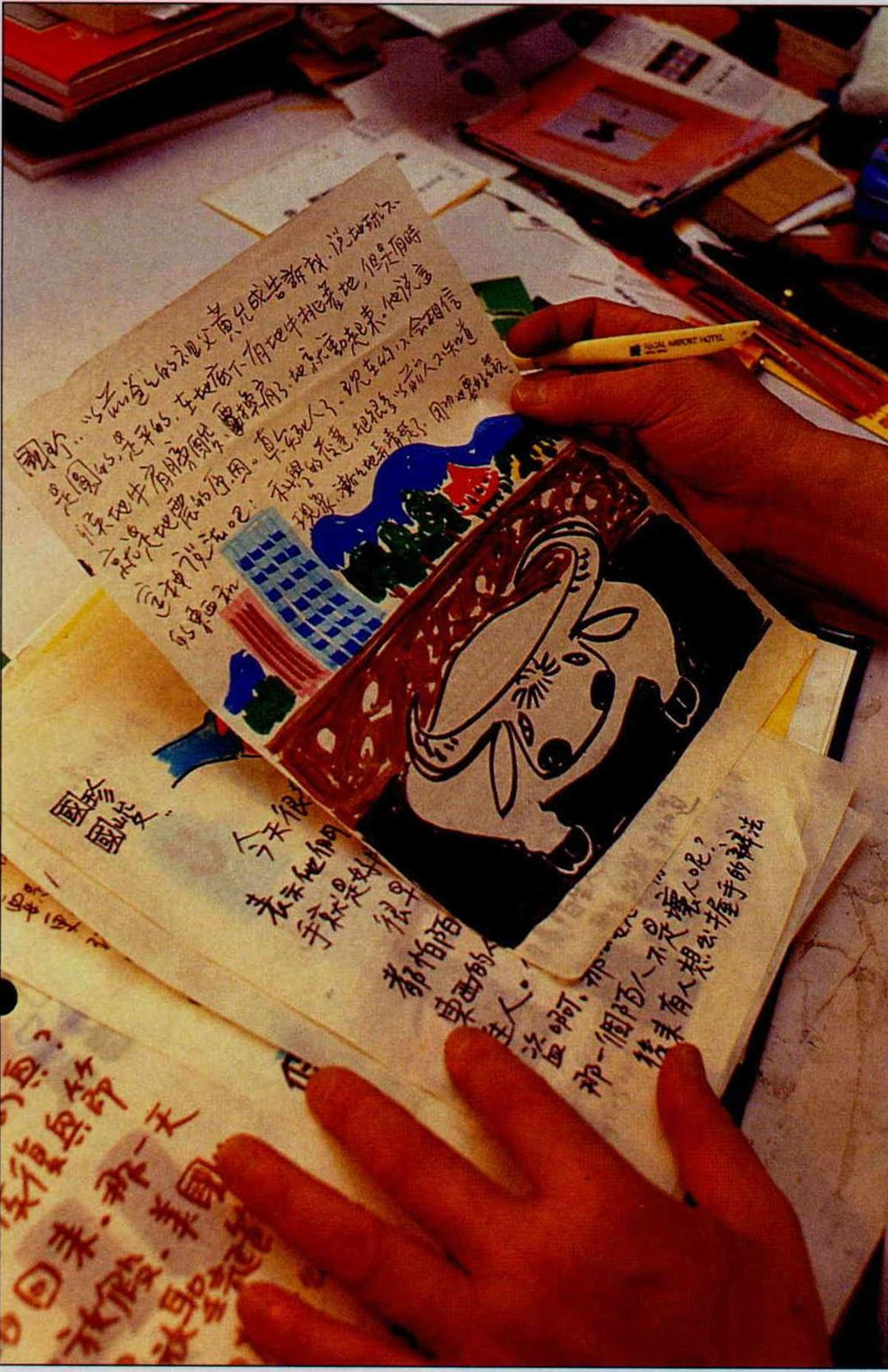

ITRI is not only the acronym for the Industrial Technology Research Institute; if you tack on a "DE," you get the initials of the six major concepts that drive it--innovation, teamwork, respect, industriousness, dedication, and excellence.

p.97

Although they call themselves a "scientific oddity," the variety of skills among the ITRI staff is a spur to creativity.

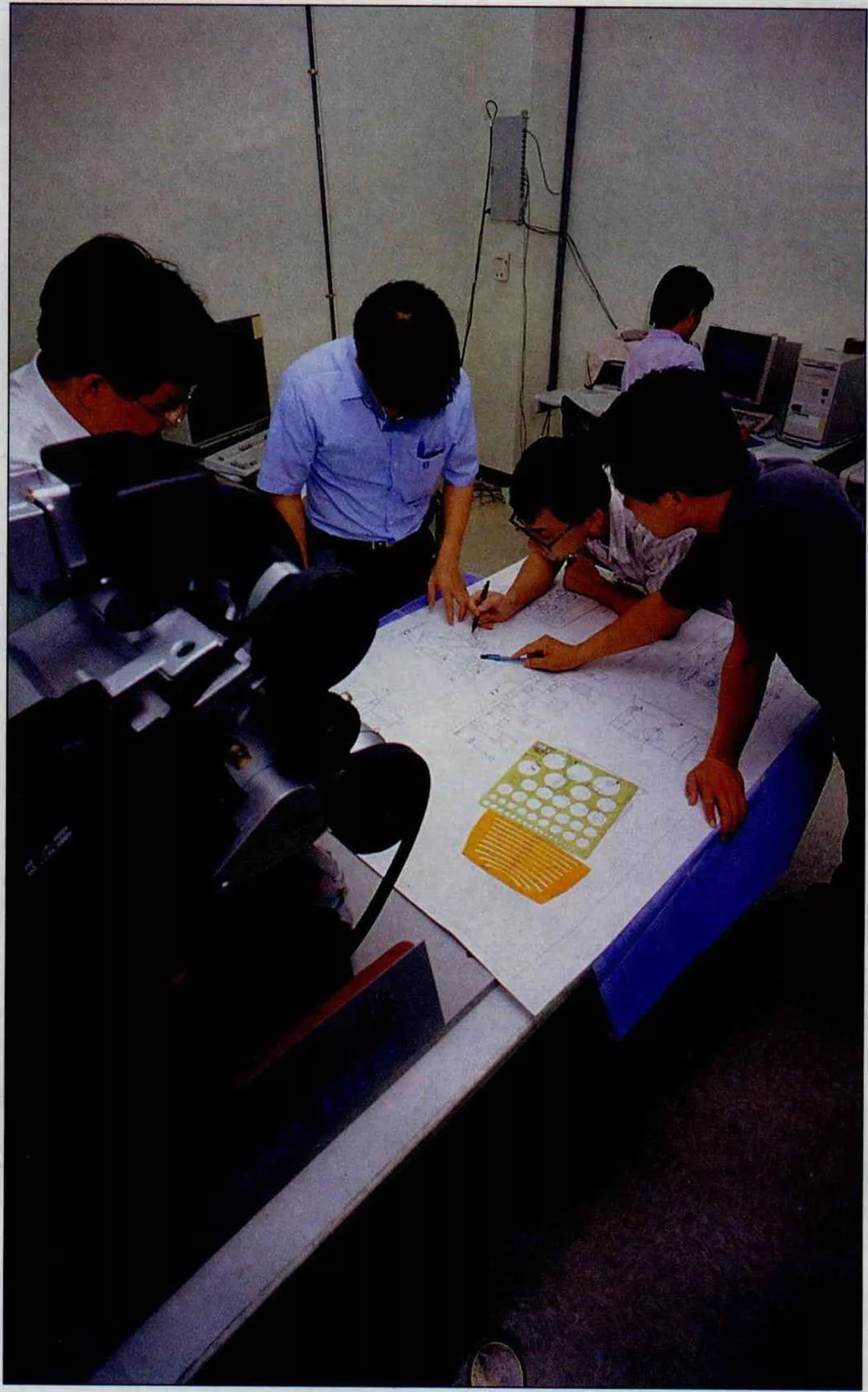

p.98

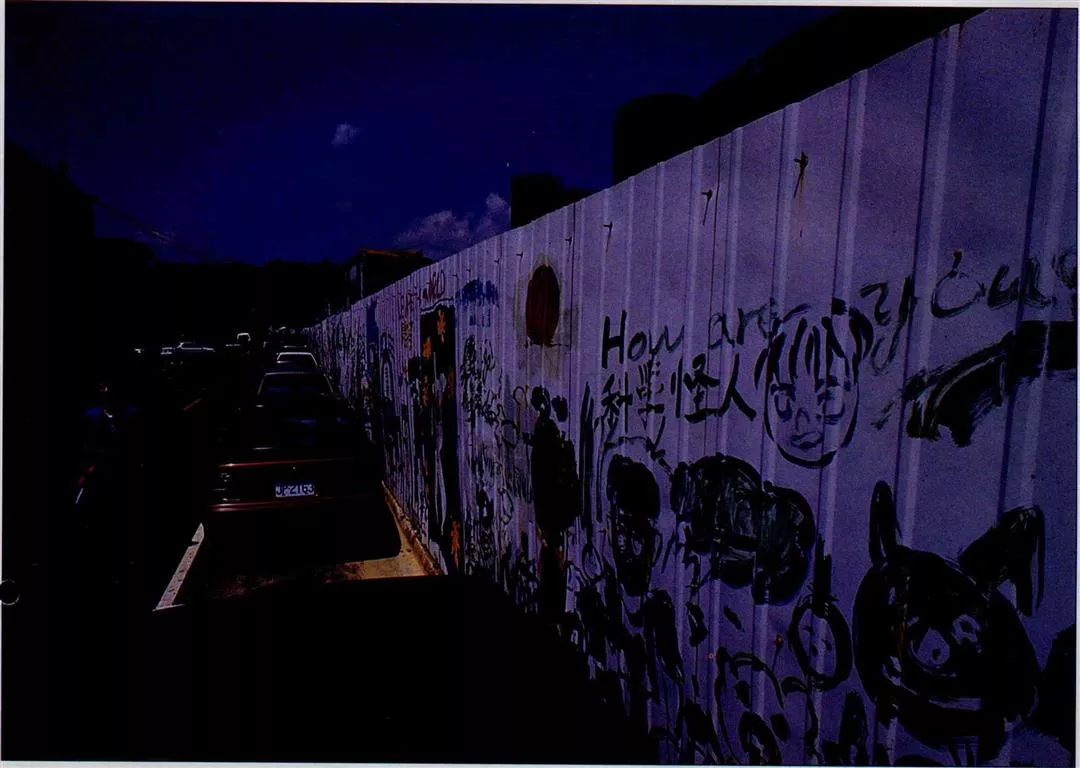

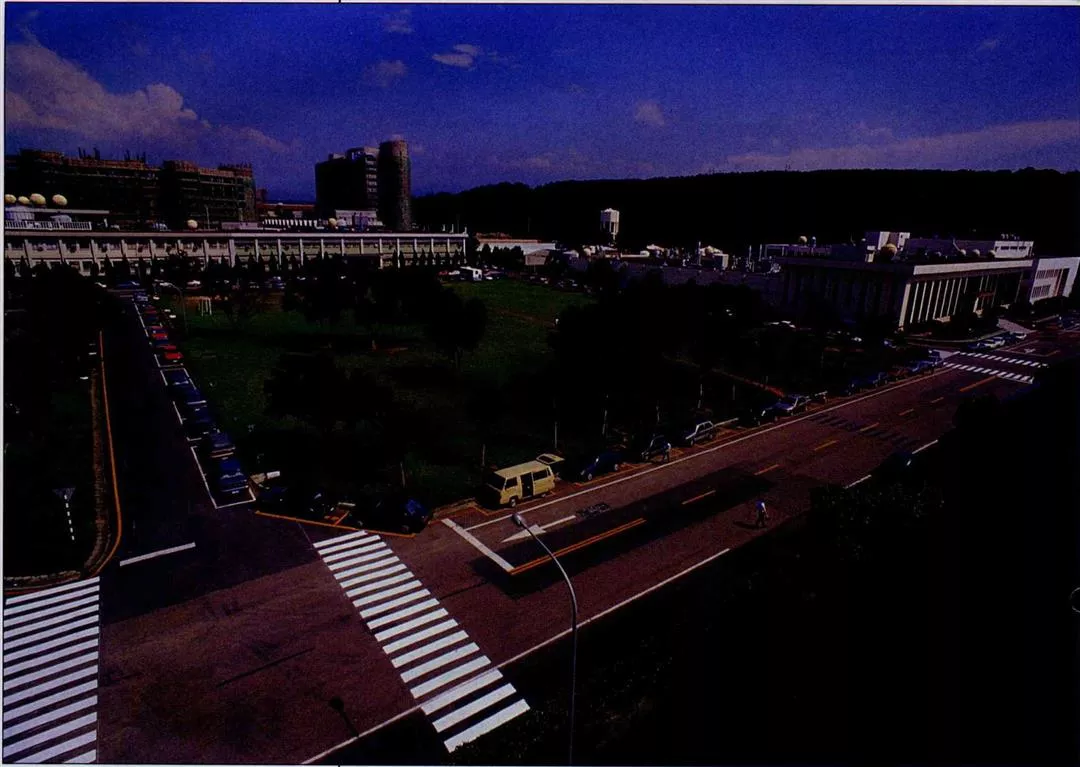

Quiet and even a bit uninspired, the main area of the Institute rarely sees people strolling about; everybody has their heads buried in their respective labs.

p.99

The newly-completed national-level "submicron lab" is the first demonstration factory in the country for wafer integrated circuits. Given the requirement of a "dust-free environment," workers can only go in "fully protected."

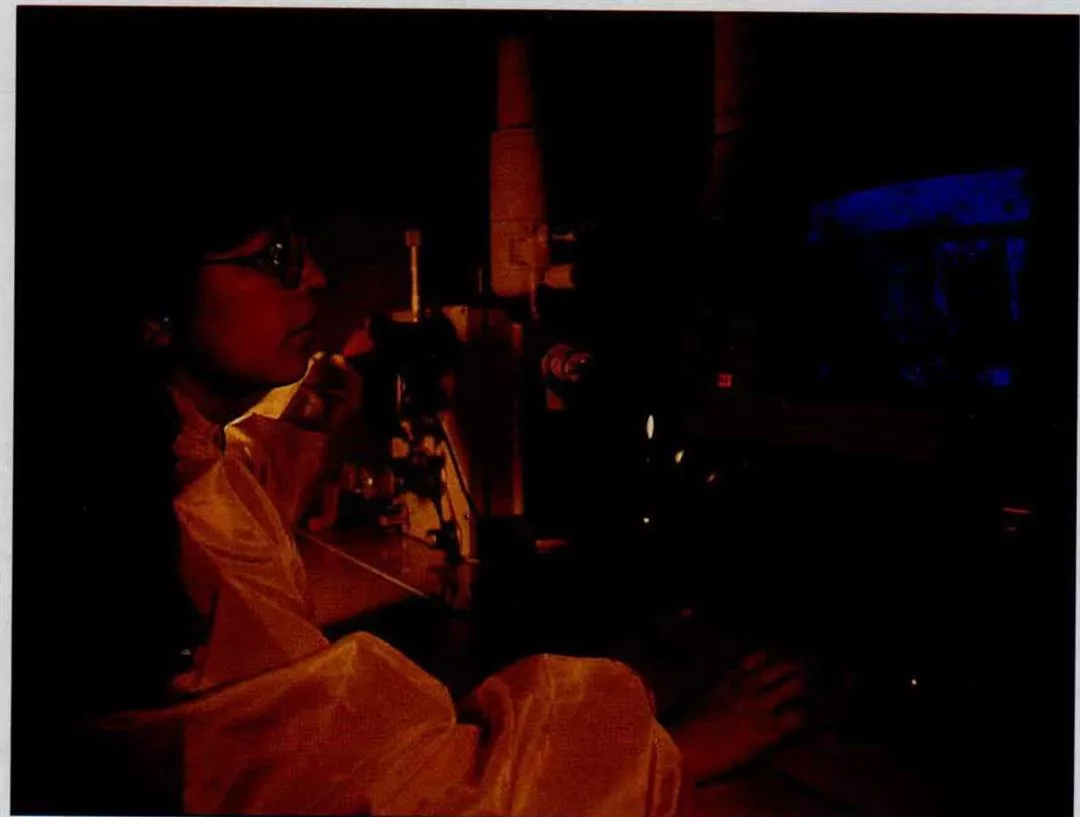

p.99

Outsiders often think ITRI must be virtually all-male, but is fact women account for a quarter of the staff. And the women don't play second fiddle to the men in either research or factory visits.

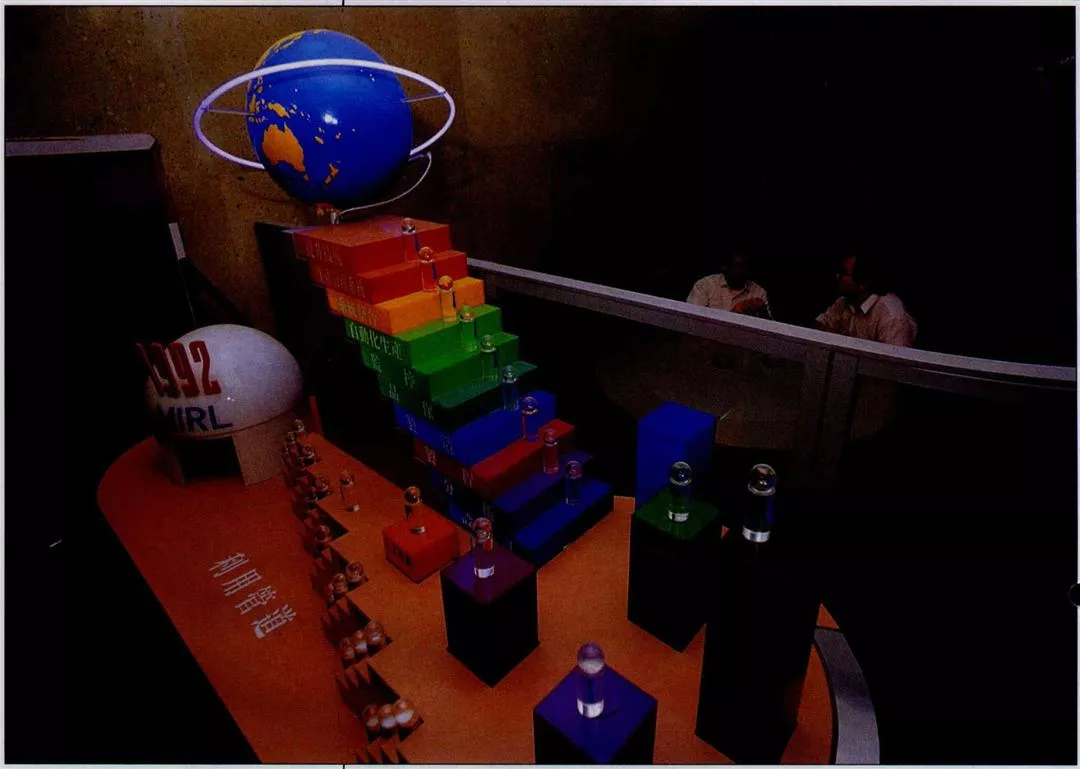

p.100

Developing advanced technology, assisting traditional industries to upgrade, and assisting small and medium enterprises, ITRI is the main technical support unit for the nation's 80,000 manufacturing enterprises.

p.101

The common engine development program is entering its third year, employing technology purchased from Lotus of Great Britain, it is hoped that the domestic auto industry can stay competitive even after the R.O.C. enters GATT and the car import invasion begins.

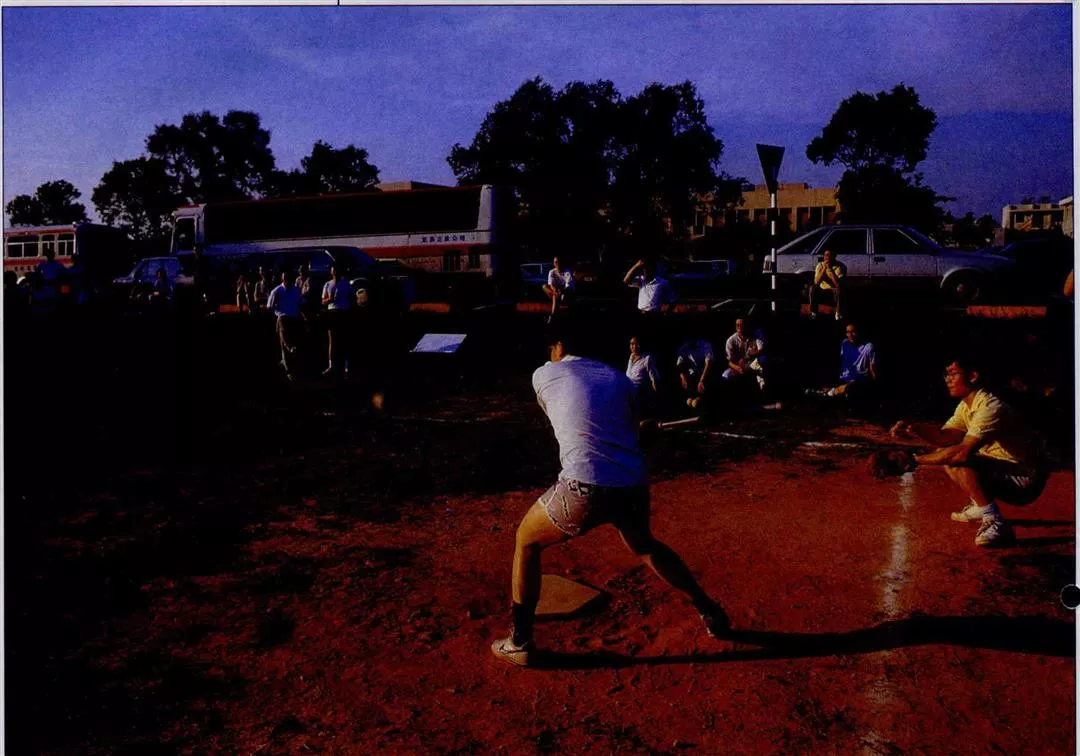

p.102

It's good to relax at dusk after a day buried in research.

p.104

There are many employees who commute daily from Taipei to Chutung, and they don't want to waste the time they spend in transit.

Outsiders often think ITRI must be virtually all-male, but is fact women account for a quarter of the staff. And the women don't play second fiddle to the men in either research or factory visits.

Developing advanced technology, assisting traditional industries to upgrade, and assisting small and medium enterprises, ITRI is the main technical support unit for the nation's 80,000 manufacturing enterprises.

The common engine development program is entering its third year, employing technology purchased from Lotus of Great Britain, it is hoped that the domestic auto industry can stay competitive even after the R.O.C. enters GATT and the car import invasion begins.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)