Chen Ruey-hwa: An Outstanding Woman of Science

Chang Chiung-fang / photos Chen Mei-ling / tr. by Phil Newell

May 2016

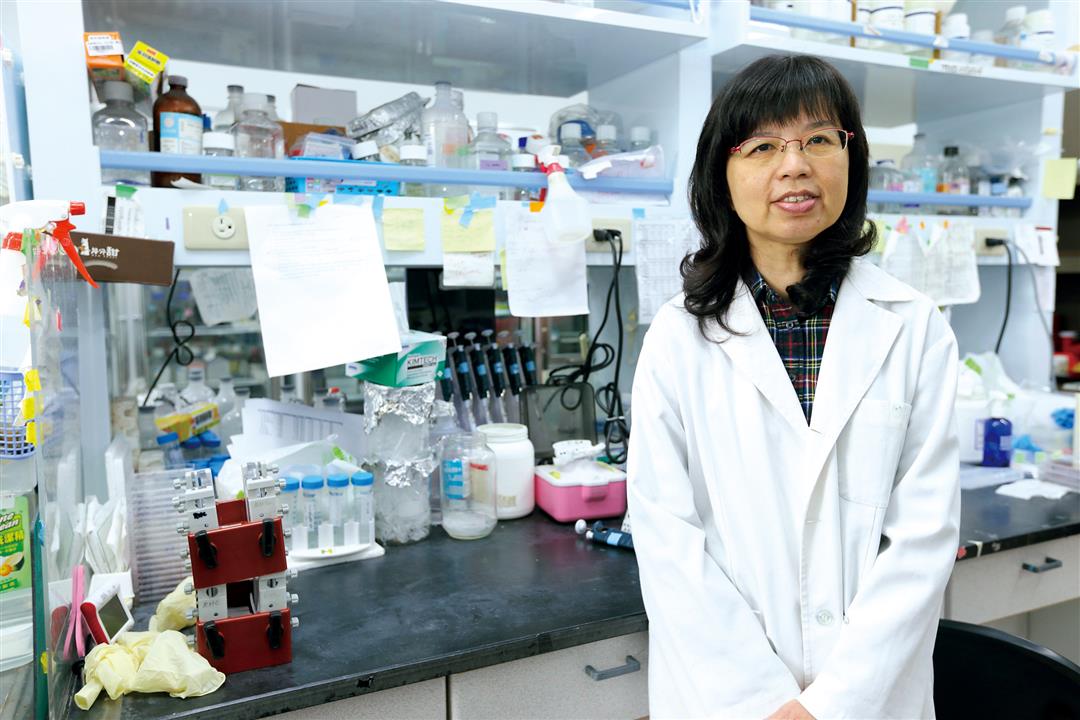

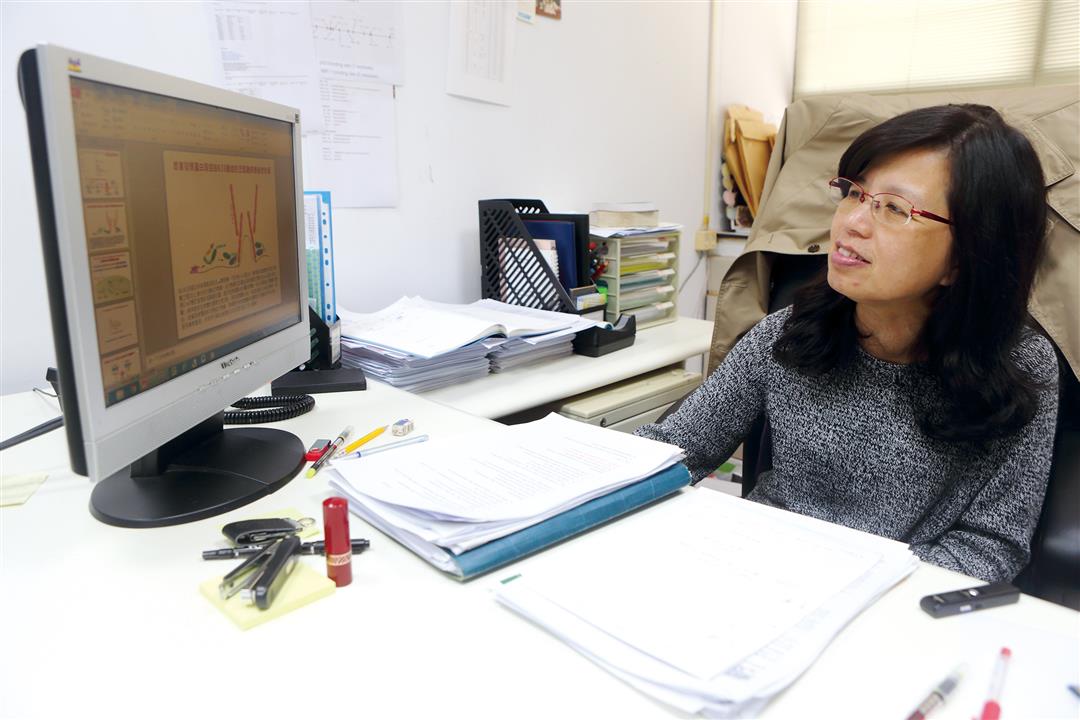

On March 19 of 2016 Dr. Chen Ruey-hwa, a distinguished research fellow at the Institute of Biological Chemistry of the Academia Sinica, was named as this year’s sole recipient of the Outstanding Women in Science Award.

How has Chen made herself so noteworthy, excelling in a field mostly dominated by men? Does she have three heads and six arms, like some Buddhist deity? Is she some kind of Superwoman with amazing powers?

When you first meet Chen Ruey-hwa, you might be surprised at how thin and frail she appears. Her slender frame contrasts sharply with the robustness of her scientific research.

In March Chen Ruey-hwa was named winner of the Outstanding Women in Science Award. Even among current students at her alma mater, the elite Taipei First Girls High School, she is seen as a towering figure. (courtesy of L’Oréal Taiwan)

Cancer suppression discoveries

The research for which Chen Ruey-hwa was awarded the honor reserved for Taiwan’s most elite women scientists touches on three main areas.

The first area is the “ubiquitination” of proteins—the attachment of ubiquitin, a small regulatory protein, to another protein. Ubiquitination (also known as “ubiquitylation”) is a kind of protein modification, and another meaning of the Chinese term for “modification” is to dress up or put on makeup. Chen uses some wordplay in trying to describe her research in layman’s terms: “It’s just like a change of costume—a protein that has been ubiquitinated alters both its appearance and the roles it performs.”

The ubiquitination process involves three steps—activation, conjugation, and ligation—each catalyzed by a different class of enzymes. The third step is the most important, for it determines which protein the ubiquitin will bind to. In humans there are up to 1000 different enzymes available for the third step, and they are known as “ubiquitin ligases” or E3s. One of these E3 enzymes, called “Kelch-like protein 20” (KLHL20), is critical in mediating which protein will be modified. This is the focal point of the lab’s research work.

“By studying the E3 enzymes, we have been able to make progress in many directions,” Chen relates. One of the most important directions is tumor suppression. Studies by Chen and her colleagues show that E3s will modify the tumor-suppressing protein PML (promyelocytic leukemia protein). Modified PML is then degraded by proteasomes, which are protein complexes within living cells that break down unneeded or damaged proteins. When tumor suppression proteins are broken down, tumors can grow rapidly.

Chen and her team have further discovered that production of KLHL20 is regulated by a protein named hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α), which cells produce more of under conditions of hypoxia (low levels of oxygen in the body’s tissues).

“The most problematic issues in clinical treatment of tumors are metastasis and drug resistance.” Chen’s research shows that raised levels of HIF-1α increase the production of KLHL20, which in turn promotes PML ubiquitination and degradation. A vicious circle is created in which PML is degraded, allowing tumors to metastasize and enabling them to resist chemotherapy. “If we can break this vicious circle, then we can control tumor growth,” concludes Chen.

Protein ubiquitination is one of the focal points of Chen’s research work.

Unlocking the mysteries of autophagy terminators

Chen’s second area of specialization is basic research related to ubiquitin.

As Chen explains, among the 76 amino acids in ubiquitin, there are eight “loci” (seven lysines—K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63—and methionine) that may serve as points for ubiquitination. When proteins are modified by the attachment of ubiquitin chains at different loci, they perform different functions.

For instance, K48-linked chains serve as proteolytic signals that target substrate proteins for degradation in proteasomes. Chen explores the functions of new ubiquitin chains, and was the first to discover the functions of proteins with K33-linked chains.

The third major area of research is related to autophagy, which is another mechanism for degrading and recycling cellular material. An example of this process, Chen says, is the way that under conditions of nutrient starvation, cells in the human body break down their own proteins and fats and convert them into energy. During the autophagy process, targeted constituents of the cytoplasm are isolated from the rest of the cell within a double-membraned vesicle called an autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with a lysosome and the contents are degraded and recycled.

Chen explains that the scientific community already knew that once initiated, autophagy within cells would increase in intensity for a time, but then would decline in intensity and eventually cease or “turn off.” But it was not known why the process would turn off, and it was her research that uncovered the mechanism by which autophagy is terminated.

“When cellular autophagy starts, several proteins are activated to form an autophagosome. When this protein complex is activated, KLHL20 is recruited to conduct ubiquitination, and the targeted material is gradually degraded.” Chen explains that KLHL20 plays a master role in the interplay between autophagy and the ubiquitin–proteasome system.

The reason this mechanism is important is that if autophagy does not turn off, it will lead to cell death. Using mouse models and cell-based studies, Chen and her team found that failure of autophagy termination also promotes muscle atrophy.

Chen says that it is already known that many diseases are connected to cellular autophagy. Some, such as the muscle atrophy produced by diabetes, are the result of excessive autophagy. Others are the result of insufficient autophagy. For example, Alzheimer’s disease is caused by buildup of proteins. “If we can suppress or strengthen the action of KLHL20, so that autophagy can continue uninterrupted or, alternatively, be turned off, then perhaps we can treat or cure these conditions.”

Using diabetic mouse models, Chen and her team found that failure of autophagy termination can lead to muscle atrophy.

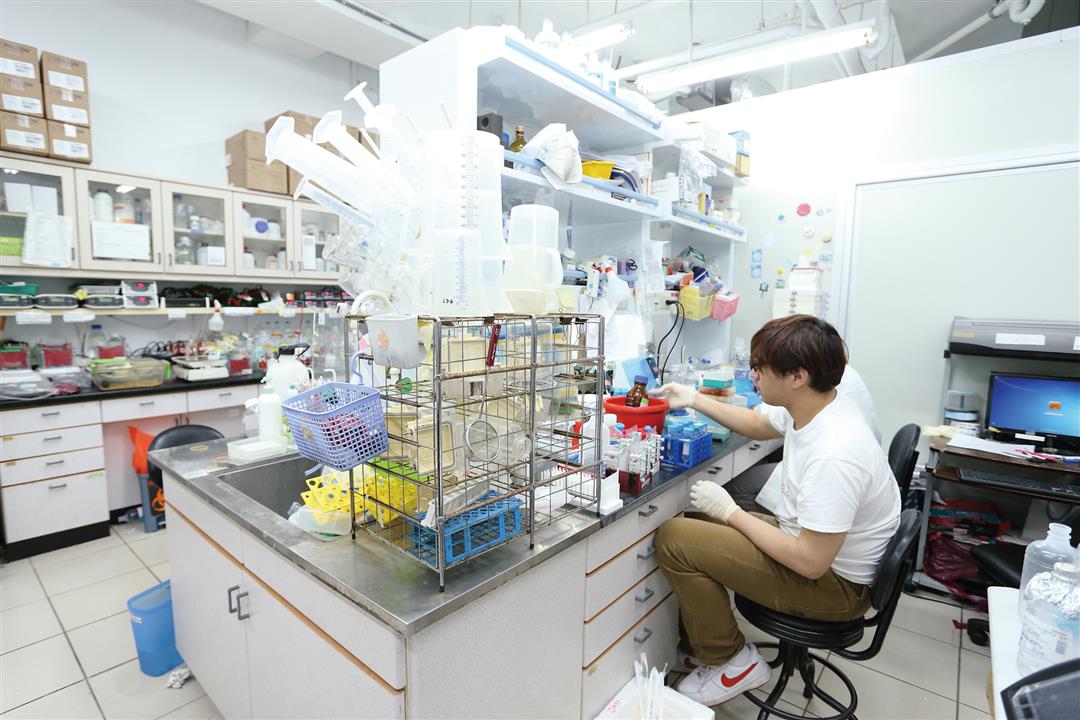

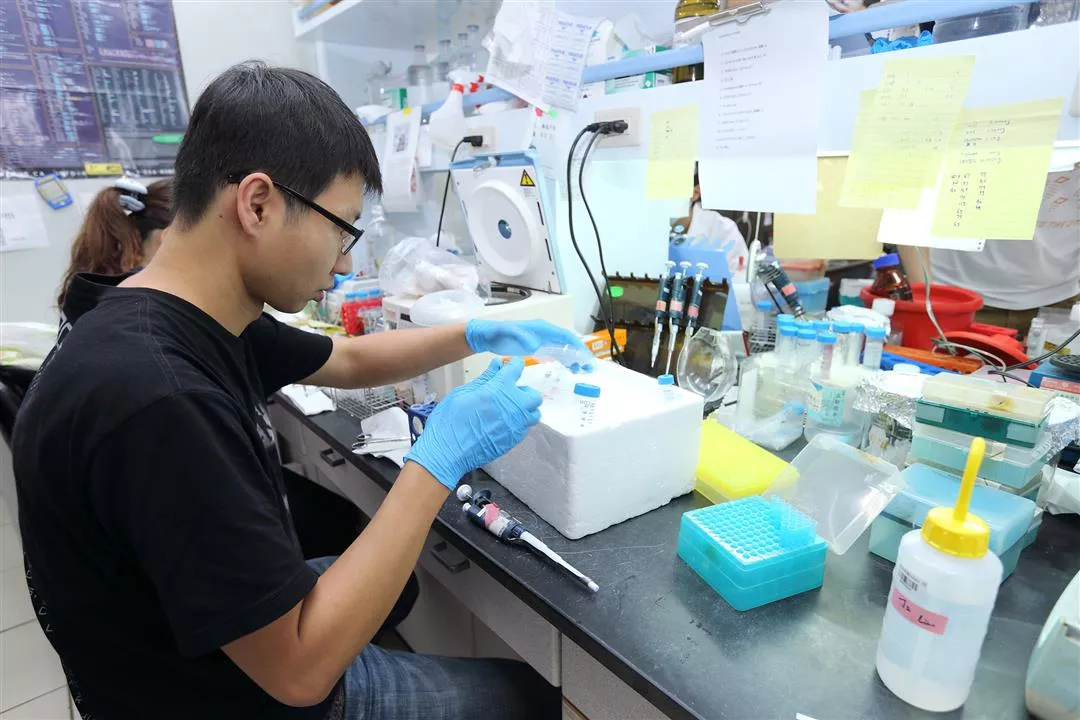

Addicted to research

“When I was young I didn’t really know what I wanted to do,” says Chen. After she tested into the Institute of Biochemical Sciences at National Taiwan University, one of the professors, Lee Sheng-chung, mentored her and helped her get her foot in the door of scientific research, and she fell in love with it. The lab that she now heads up at the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Biological Chemistry is quite expansive, with a staff of 14 or 15. This is quite an achievement considering that only one-fourth of the researchers at the IBC are women. “We work all year round. Students who just want to cruise through to a diploma without working hard won’t come to join my lab,” laughs Chen.

There is no question that Chen is able to dedicate herself completely to research because her partner is also in the sciences. She says that the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Molecular Biology (where the male–female ratio among researchers is about 50:50) did a statistical study which showed that the majority of partners or spouses of female scientists are themselves academics, but that this is not necessarily the case for men, whose wives come from a wider variety of career backgrounds. In other words, only a man who is himself in academia is likely to be able to understand and support a woman scientist who spends night and day in the lab.

Using diabetic mouse models, Chen and her team found that failure of autophagy termination can lead to muscle atrophy.

Baby bottle in one hand, beaker in the other

While she may be one of the nation’s most outstanding women scientists, in the section on her resumé for “previous experience” Chen also has the job title “mother.”

She recalls that during her time doing postdoctoral work at the University of California San Francisco, she and her husband worked “shifts” so that they could handle both work and childrearing. Chen went into the lab at five in the morning and returned home at one in the afternoon to take over parenting duties. Her husband started work in the afternoon and continued until late at night.

After returning to Taiwan, when the children were still very young, husband and wife had to alternate working on weekends. “During that period, the children saw only Dad, or they saw only Mom, like a single-parent household,” laughs Chen.

When her children had grown a bit, she started bringing them to work with her. Oddly enough, neither of these two kids who virtually grew up in labs at the Academia Sinica ended up going into science. The elder studied design; the younger studied business administration.

In the past, Chen, whose strength has always been basic research, felt no interest in starting a company or doing business like technology transfer. “But now that I’m getting older,” she states, “I feel like I want to make some contribution to society.” The ability to control KLHL20 would be of tremendous value in the treatment of cancer and other diseases and in the development of new medicines. Therefore she has been working with Academician Tsai Ming-daw, a structural biologist, to figure out methods to break the bonding between KLHL20 and PML. “First we have to determine how these two proteins combine at the structural level; only then can we design small-molecule drugs to break the linkage between them.”

It is a long road from basic research to practical applications. But Chen, who has been doing scientific research for 30 years, while not rushing forward rashly, is undaunted. “This is just the way biology and medicine are,” she says with equanimity. But there is determination in her voice as she adds: “If we succeed, the results will surely have an enormous impact on the treatment of cancer.”

When you look at Chen Ruey-hwa, you won’t see any extra heads or arms, nor will you see a cape or any other evidence of superpowers. But you will see a prime example of Taiwan’s women at their most earnest and purposeful.

Chen’s lab at the Institute of Biological Chemistry of the Academia Sinica has a large staff and never takes a day off. (photo courtesy of Chen Ruey-hwa)

Chen’s lab at the Institute of Biological Chemistry of the Academia Sinica has a large staff and never takes a day off.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)