"Mango Missionary" Lin Tzong-shyan and the "Golden Miracle"of Taiwanese Agriculture

Kuo Li-chuan / photos courtesy of Lin Tzong-shyan / tr. by Anthony W. Sariti

July 2008

Taiwan agriculture's "four treasures"-the butterfly orchid, Oolong tea, Taiwan tilapia and the mango-are all part of the "A-Team" that has established a firm foothold in the global marketplace. In recent years it has been mangoes that have scored success after success. These include the Irwin mango, which has fought its way into the high-quality Japanese gift box market, and the Chin-huang mango, which has found such favor among Australians. The mango will soon make its appearance in August in Beijing as the official Olympic fruit, an event we can expect will usher in another new and unique page for Taiwan's "golden miracle."

Living in the "fruit kingdom," Taiwanese enjoy top-quality, inexpensive fresh fruit in season all year round. It is hard to imagine that the mangoes one sees everywhere in midsummer undergo a huge jump in price in Japan where they can sell for close to NT$1,000 apiece. Another startling fact is that in ten short years the value of overseas mango sales grew almost 100-fold, from NT$3 million in 1996 to over NT$310 million in 2007. This is another demonstration of Taiwan's superb agricultural technology.

Although the mango is an introduced species, with careful cultivation by agricultural experts it has become a trademark fruit for Taiwan. Pictured here, from left to right, are the Chin-huang, Keitt, Irwin and Haden varieties.

Foreign seeds take root

It is interesting to note that just as in English, the word for "mango" in Chinese-mangguo-is derived from a foreign word. Thus we know the fruit actually comes from overseas. When the Dutch occupied Taiwan more than 300 years ago they introduced the mango from Southeast Asia. The fruit was popularly known as the "local mango." It was small, with a green skin and rich fragrance; it had coarse fibers but also a delicious sweet-and-sour taste.

Because of the favorable growing conditions in Taiwan and popularity of the fruit, the Japanese colonial government introduced a number of varieties from India and Southeast Asia during the occupation. After the arrival of the Nationalist government on Taiwan, the Irwin, Haden and Keitt varieties were introduced from the US.

In 1961 Chang Chen-chou of the Chiayi branch of the Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction did a test planting of 100 Irwin mango seedlings from Florida in the Cheng Fruit Orchard in Yuching, Tainan. After three years of meticulous care, four trees survived and bore fruit. The fruit was large with a bright red, thin skin and a finely textured, golden-colored flesh with a very sweet taste. After this Irwin mango, nicknamed the "apple mango," came onto the market, people were amazed and a buying craze ensued.

The interior of Tainan, mostly composed of mountain slopes, had up to that time been suitable only for growing dry land crops, like cassava and sugar cane. Fruit farmers, seeing there was considerable profit in mangoes, vied to be first to plant the trees. The main production areas were Nanhsi, Yuching, Nanhua, Tsochen, Shanshang and Kuantien. Of these, Yuching was the biggest, as well as the birthplace of the Taiwan Irwin mango. For this reason, it has been called the "home of the mango."

Bloom without fruit

Nevertheless, after a few years of prosperity at the end of the 1960s a great number of Taiwan's mango trees began to bloom but bear no fruit. When successfully pollinated, the fruit had reached weights of 300-400 grams and was big enough to fill the palm of a hand. But if there were no means of pollination the trees would set no fruit at all or would shed large numbers of the fruit before they were ripe. Even those that did ripen would only reach the size of a chicken's egg. These were called the "little Irwin" or the "seedless mango." The fruit tended to be flattish and thin and although they were quite tasty, the situation was not something the fruit tree farmers were happy about.

With harvests not meeting expectations, the fruit farmers realized the situation was serious, so a group went to the Taipei KMT headquarters to plead their case. The then party secretary-general Tsiang Yien-si invited fruit tree experts throughout Taiwan to form a task force and put their heads together to solve the fruit farmers' problem.

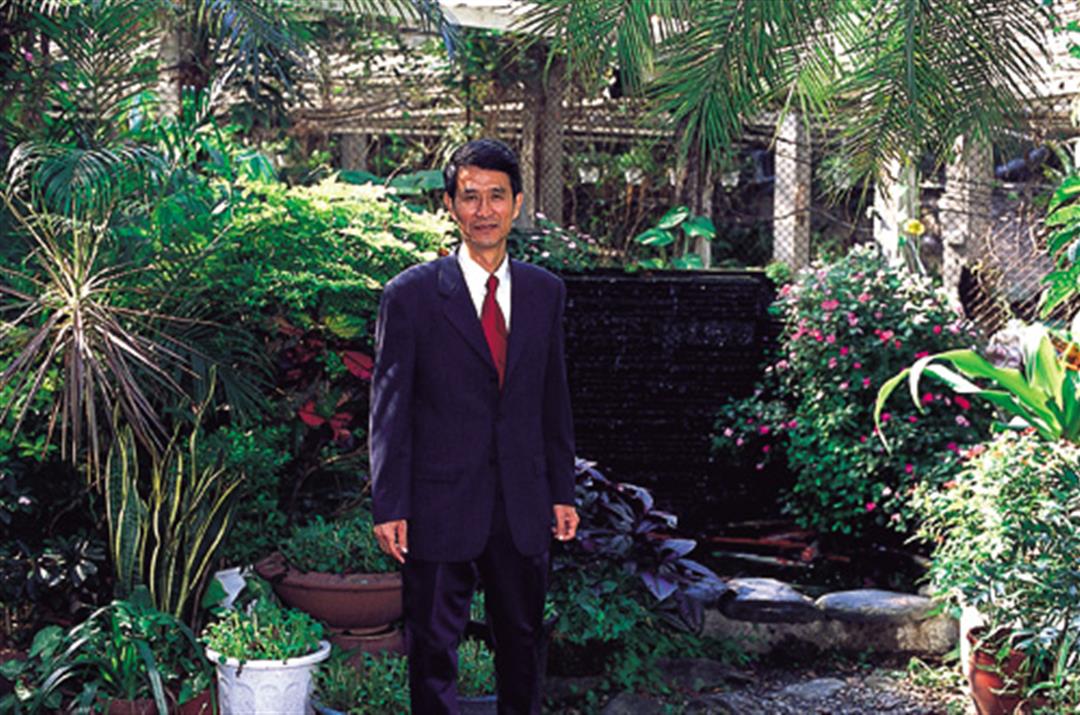

Known as the "mango missionary," Lin Tzong-shyan, former director of the National Museum of Natural Science in Taichung and currently a professor in the Department of Horticulture at National Taiwan University (NTU), says that after some investigating, the task force came up with several possible causes of this problem. Firstly, because the mango trees in Tainan were planted on mountain slopes, the soil was shallow and thus lacking in inorganic material and minerals. Secondly, the plants were too close together so that not enough light could come through and the trees could not photosynthesize adequately. Thirdly, the mango blossoming period is from December to January; when winter temperatures were low, the pollen did not germinate, leading to incomplete pollination. Finally, if there is rainfall during the blossoming and fruiting period, the moisture may induce anthracnose disease. Any of these factors could have led to the mango trees blossoming but not bearing any fruit.

The "culprits" had been revealed, but how was the problem to be solved? There wasn't a clue on how to do this. A graduate of the horticulture department at National Chung Hsing University, Lin Tzong-shyan still remembers that when he sat for the examination for a government-sponsored overseas scholarship in 1978 the exam question was, in fact, "Causes of mango trees blooming but not bearing fruit." The difficulty of the problem and the government's urgent concern were obvious.

Taiwan has many mango varieties, as well as many ways to use them. They may be dried, or used to make alcohol or vinegar. When summer rolls around there is mango mousse or a mango slushy-and who can resist that!

The stench of a pig's head

In 1979 Lin Tzong-shyan entered the Department of Pomology at the University of California, Davis, and four years later obtained his PhD in plant physiology. He then joined the teaching staff at NTU. Li Chin-lung, later chairman of the Council of Agriculture and at the time chief of the COA's domestic production department, sought Lin's help and asked him to visit the mango production area to get a concrete understanding of where the crux of the problem lay. Lin himself was anxious to contribute the knowledge he had learned. He made the orchard his laboratory and conducted energetic inquiries in a scientific spirit.

"At the time there was an idea going around that the winters in the south were dry, that there was insufficient water and that this was the chief reason the mango trees were not fruiting." Lin then conducted an experiment on a mango orchard in Fangshan, Pingtung. He irrigated a test plot and left the control plot alone. When it rained, the control plot was hurriedly covered over with plastic sheets to block out the rain. A few times when Lin heard the sound of rain in the middle of the night, he immediately got up, braved the cold wind and sudden downpour, and groped his way through the orchard in the darkness to cover the control plot with the sheets. The memory of a cold, shivering body, desperately at work, remains crystal clear in his mind to this day.

The results of the experiment were startling. The trees that were irrigated turned out to produce more "seedless mangoes." This demolished the argument that insufficient water causes mango trees not to bear fruit.

Following this experiment, Lin carefully observed the orchard environment and discovered that the original ecological chain of the mountain slopes on which the mango trees were planted had been all but destroyed owing to the fruit farmers' major development of the area, by the use of fertilizer and ground clearing and the massive spraying of pesticides to prevent anthracnose. Naturally, these pesticides also killed off insects that played a role in pollination. Add to this that the area was planted only in mango trees and that it is difficult to attract pollinating insects for only a single species, and the problem was made even worse.

When he was investigating Yuching in 1985, Lin took a stroll through the countryside. There he witnessed the residents performing a Daoist religious ceremony. When the ceremony was over, the pork from the sacrificed pig was equally divided among the residents and the leftover pig's head was just tossed away at the foot of a mango tree. The smelly pigs head attracted a large swarm of blowflies. These large-headed flies buzzed around the pig's head in a disgusting way but Lin discovered to his surprise that several mango trees next to the one with the abandoned pig's head were heavily laden with fruit. Could it be that this blowfly with its shiny, metallic-green body, popularly called the "golden fly," was the savior that could solve the mango pollination problem?

Triple jump

Lin Tzong-shyan then persuaded Wu Ching-chin, a fruit farmer, to begin using a patchwork pattern in 1986 and set out his trees such that eight mango trees would surround rotten meat or the entrails from an animal that would be placed there. After toughing out a few days of a terrible stench, Wu noticed the blowflies were nowhere to be seen. In for a penny, in for a pound, Wu took the rotten meat to the market where he placed it next to the garbage piles. After getting the blowflies to lay their eggs in the meat, he returned it to the mango trees.

Other fruit farmers raised their eyebrows at Wu Ching-chin's "strange behavior." To make matters worse, his orchard bordered the road and the stench of the rotten meat made people hold their noses and shout curses at him. But next year's harvest brought a broad smile to Wu's face. Before the fruiting problem had been solved, the average yearly harvest per hectare was five to eight metric tons. After the rotten meat treatment, the first year of production saw a two-fold increase, and the second year the harvest per hectare reached 25 to 30 metric tons!

What made people curious was the pollinating insects. How was it these were the blowflies and not the bees that most people were familiar with? Lin said that during the 1960s, in fact, an agricultural expert in India had published a book proving that it was the fly that pollinated mango trees. Lin had then asked Professor Wu Wen-che of NTU's entomology department to come and assist him. Wu brought ten research assistants along and released 100,000 bees into the mango orchard. After a half hour he made a count and discovered that only a little over 200 bees were visiting flowers. "The mango belongs to the plant family Anacardiaceae, and bees just don't like it," explains Lin.

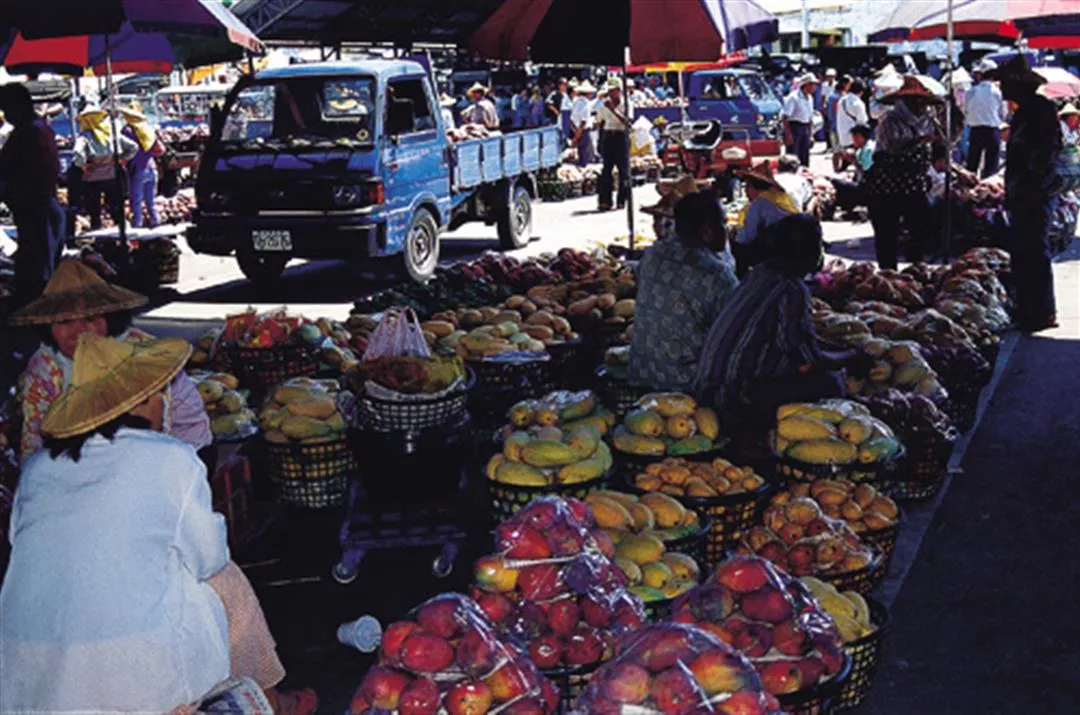

Every summer the "mango market" stretches out some two kilometers long in Yuching Township, Tainan. The market always attracts large numbers of stall fruit sellers and tourists who come, vying to be first to taste the new crop.

Discarded fruit

At last an answer had been found to the non-fruiting problem that had baffled agricultural agencies in Taiwan for over a decade. But due to image concerns related to environmental health, the government ordered that the solution should not be made public. Nevertheless, the information was passed around by word of mouth by the fruit farmers. Lin Tzong-shyan emphasizes that the rotten meat had to start being put into place when the flower clusters were between five and ten centimeters in size because when they reached this size the blossoming onset was from two to three weeks later, just enough time for the eggs laid by the blowflies to hatch in large numbers.

The interesting thing was that because most of the mango orchards in Tainan were located in mountainous areas, each year during the blossoming period shrewd businessmen would bring truck after truck of rotten, stinking fish to the area to sell to the fruit farmers. Red paper advertising banners would be hung all along the way on electric poles announcing "Good News for the Blossoming Period-Trash Fish Have Arrived!"- a truly impressive sight. The mango non-fruiting problem also occurred in Fangshan, Pingtung in 1990. The same solution was used, the same selling of trash fish took place and the same impressive red banners reappeared in Pingtung.

After the problem was handily taken care of, mango production in Taiwan experienced enormous growth. During the high production period of mid-summer, on either side of the provincial highway in Kuantien, Tainan, the mango market stretches for almost two kilometers where fruit stall operators are always seen selecting and buying fresh mangoes. The parking area at the Yuching fruit and vegetable wholesale market is filled with sightseeing buses as tourists from all over Taiwan are busy buying mangoes during this spectacular display, putting huge smiles on the faces of the fruit farmers selling their products.

But who would have thought that the wheel would reverse itself? Mangoes became hot sellers and fruit farmers rushed to plant more trees. But this led to overproduction and to farmers angrily throwing away their fruit as prices fell so low that they could not recover their costs. This was something that Lin, the mango savior, had never imagined.

This blowfly, popularly known as the "golden fly," was the hero in the mango pollination problem.

Supply outstrips demand

Because of the climate in Taiwan, the mango season moves gradually from south to north. The "local mango" matures the earliest and is first to hit the market in April around the time of Tomb Sweeping Day. Following close behind are the Irwin and the Chin-huang, a mango shaped like a small elephant tusk weighing about two kilograms developed by Huang Chin-huang, a farmer from Liukuei in Kaohsiung. These two star varieties both make their market appearance in mid-May. Next comes the Haden but since the Haden produces less fruit, farmers have gradually reduced production because of a low profit margin. The Keitt is the last to mature. With proper care a Keitt mango can reach one kilogram in weight and because it comes to market in September it is popularly known as the "September mango."

Fangshan in Pingtung, on the southern end of Taiwan, is very windy with ample sunshine since it is located along the coast. The mango varieties here ripen before others, so they command a superior price. By comparison, when the mangoes from Tainan to the north, that are produced in large numbers but mature later, come to market, supply often exceeds demand. In addition, the novelty of tasting the season's first fresh fruit has past. This all results in Tainan mangoes having a great reputation to no avail as they only fetch low prices on the market. In an angry gesture, farmers dumped more than 50 tons of mangoes in the Tsengwen River to highlight the severity of the problem.

Lin Tzong-shyan says that aside from the pollination problem having been solved, the key factor behind mango overproduction is too many farmers. Taiwan has many kinds of fruit, and some 180,000 hectares are planted with fruit trees. But mangoes are the favorite among farmers, occupying 10% of the planted area. With a compressed growing season, this makes it difficult to avoid unsaleable gluts of the fruit.

Beginning in 1990, with funding from the Council of Agriculture, Lin Tzong-shyan invited experts from all sectors to set up a technical service team over a five-year period that would advise fruit farmers on how to lower production costs and raise quality. In addition to opening up new access roads and thinning both trees and fruit, "raising weeds" was to be practiced inside the orchards. This meant the grass and weeds around the fruit trees were to be left to grow and not cut, to take advantage of their ability to retain moisture and warmth and improving the quality of the soil, thus reducing soil erosion.

In view of the small size of Taiwan's domestic market, Lin Tzong-shyan believes the most urgent tasks for agricultural agencies are to tackle the problem of unsaleable gluts of fruit, and to develop international markets. The photo shows a mandarin orange grove.

Going international

To survive, the mango industry in Taiwan has utilized production and marketing regulation and has made great strides toward meeting high quality and environmental demands. Also, in view of the small domestic market, the government has taken on the challenging international market as a top priority and has begun actively to gather data and make preparations.

In the late 1990s Europe experienced outbreaks of mad cow disease and foot-and-mouth disease, which led to an awakening of consumer consciousness. In the fiercely competitive international market, consumers are paying increasing attention to food quality and safety. European fresh produce retailers thus initiated EurepGAP (Euro-Retailer Produce Working Group Good Agricultural Practices) in 1997 and within three years drafted standards that went into effect in 2000.

In January, 2002, Taiwan joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). The market was opened up and imported fruit began pouring into the country. On the one hand Taiwan agriculture was facing ruthless global competition, but at the same time it now had the opportunity to market its products globally on an equal footing.

On this account, the Council of Agriculture put forward a policy centered around "quality, safety, leisure, ecology." The most important element in this approach was to develop "safe agriculture." This set up a mechanism for agricultural products that provided information on the entire process, from the management of production in the field all the way to the consumer's dinner table, in order to meet the demands of EurepGAP and the Japanese "Production Record System."

Through the combined efforts of government and citizens, and with the guidance of experts headed by Lin Tzong-shyan, Fruit Tree Production and Marketing Team #20 of Nanpei, Tainan, finally passed and received EurepGAP international certification as a result of its rigorous quality control and monitoring of the entire production process.

Lin emphasizes that "safe agriculture" not only can raise consumer confidence in domestic agricultural products, the selling price of these products may rise because of the "empowerment" they get from certification. At the same time, this win-win approach, concerned as it is with both farmer income and consumer food safety, will be the niche for Taiwan agriculture as it competes in the future with other low-production-cost countries.

The "fruit ambassador"

The importance the government has given to overseas sales of mangoes has gradually shown results over the past few years. In Southeast Asia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Australia and Spain, Taiwan mangoes are in evidence. Last year Yahoo! Japan held a vote for "the world's best mango." In a Japanese online survey the Taiwan mango received a whopping 76% of the votes, far ahead of the Philippines, which accounts for a large number of imports, and Japan's own main production area of Miyazaki Prefecture. Last year the total export value of Taiwan mangoes reached US$9.83 million. This represented a 1.3-times growth compared with the 2006 figure of US$4.28 million.

The dawn of the "golden miracle" of the Taiwan mango is just breaking. One of the chief promoters, Lin Tzong-shyan, is still cautious. He is hoping that one day the mango will truly become a "fruit ambassador" and carry with it the sweetness of Taiwan and its people throughout the world!

The Irwin mango, allowed to ripen naturally on the tree, is very fragrant and sweet.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)