Green Burials Catching On in Taiwan

Chen Hsin-yi / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by David Smith

April 2010

Tomb-Sweeping Day is a time for remembrance, whether the act is performed by an entire troupe of relatives heading off with offerings to a gravesite, or one single person thinking of a departed loved one while facing a memorial tablet. Such scenes are familiar to all of us.

However, funeral rituals and burial practices are gradually changing. Some people have begun sending their loved ones to a final resting place in out-of-the-ordinary places, such as wooded groves. The elaborate rituals of a traditional burial are not required in such instances; instead, the bereaved merely pray for the departed in silence while witnessing their return to the earth. The sights and sounds of nature cleanse the soul, and the participant awakens to the truth of the unity of all things, and the eternal existence of the spirit....

Natural burials were introduced in Taiwan some years ago, so let us take a closer look at this new, environmentally friendly way of putting the departed to rest.

In densely populated Taiwan, land is very scarce, and traditional earth burials gobble up lots of it while sullying the beauty of nature, consuming energy, and causing pollution. For this reason, the government since the 1970s has been vigorously promoting cremation and storage of ashes at columbariums. By the 1990s, the practice of cremation had gained widespread acceptance in Taiwan. Statistics from the Department of Civil Affairs of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) indicate a cremation rate of 89.11% in 2009 (99% in large urban areas), with the ashes of some 100,000 persons placed each year in columbariums. Quite clearly, "cremation plus columbarium" has become the standard way of handling dead bodies in Taiwan.

From the standpoint of environmental sustainability, however, building towering columbariums at mountain temples across the island doesn't really go to the heart of the problem. Huang Youzhi, director of the Center of General Education at National Kaohsiung Normal University and an expert in the theory of environmental fengshui and education about death, notes that once ashes are stored in a columbarium, they are there for good, which means the towers eventually fill up. Moreover, there have been cases where the proprietors of columbariums running out of capacity take advantage of the situation to jack up the price on the remaining spaces. In response, a new wave of reformers have introduced the idea of disposing of cremated remains by means of more environmentally friendly tree burials and burial at sea.

This "second round of funeral and interment reform" began in 2000. Liu Wen-shih, then head of the MOI Department of Civil Affairs, worked actively with people from the funeral services business as well as government officials and academics to push for adoption of an Act Governing Funerals and Interments, which was eventually passed by the Legislative Yuan in June 2002. The new act provides for tighter government regulation of the funeral business, addresses natural burials in law for the first time, and provides subsidies for local governments to promote new types of burial practices.

(left) On the eve of Tomb-Sweeping Day, the wild flowers in the tree burial area of the Yuanshan Fuyuan cemetery sway gently in the breeze. Sections of hollow bamboo (right) are provided into which family members can pour the ashes of the deceased, returning them to the earth without a trace.

The city government of Taipei, where land commands an especially high premium, has for some years now made natural burials a key policy objective. In November 2003, a tree burial and ash scattering facility called the Fude Life Memorial Park opened at the Fude Public Cemetery in Taipei City's Wenshan District. The facility covers about 200 ping (roughly 660 square meters).

Before taking part in a tree burial, family members can choose where in the park they would prefer to have the ashes buried, and with the guidance of park personnel they themselves actually take shovel in hand to clear away an upper layer of gravel before digging a hole of 10-15 centimeters in diameter and 20 cm deep. Into this hole they place the ashes in a biodegradable bag. Then they lay some flowers over the bag, and finish by covering the hole back over. No hole is dug in the case of an ash scattering ceremony. Instead, the ashes are scattered over the ground in a designated section of the park's flower garden. After the ashes have been scattered, they are covered over with a one-centimeter layer of earth and flower petals so they won't blow away or get washed away by the rain.

To encourage tree burials and ash scatterings, these options are available completely free of charge, but people are not allowed to set up a memorial tablet or a name plaque, or to commemorate the dead by burning incense or chanting sutras.

During the first year after the introduction of natural burials, a lot of people unfamiliar with the practice called the Taipei Mortuary Services Office to protest the new development. One indignant caller asked: "How could you bury ashes under a tree? Won't that be just like the legend of Nie Xiaoqian, where she gets buried under a tree and the tree turns out to be a 1,000-year-old ghoul that takes control of her?" Another person took issue with the decision to use the word "park" in the facility's name: "How could you scatter ashes around in a place where kids will come to play? The place is gonna put a hex on the poor kids!"

The Mortuary Services Office went to great lengths to put such fears to rest, explaining that tree burials and ash scatterings are in keeping with the traditional Chinese concept of "finding peace by returning to the earth," and that such burials can enable the deceased to become one with nature. The decision to call it a park, meanwhile, was part of a conscious effort to break away from the traditional image of cemeteries as dark and lugubrious; they wanted people to show up in a different frame of mind, prepared to appreciate an atmosphere of serenity and to feel the hope that comes with knowing that life never really ends.

More and more people are in fact opting for natural burials each year. As of the end of February this year, a combined total of 1,799 persons had been laid to rest in natural burials at Fude Life Memorial Park and at Yong'ai Park, which opened in 2007 on 1.2 hectares with 6,000 burial locations scheduled for reuse on a 10-year cycle. Fully half the persons buried there are not from Taipei, thus showing clearly that natural burials are in step with the times.

As life comes to an end, perhaps the best way to affirm its value is to choose the simplest and most direct return to the earth. Shown at left is the tree burial plot at Yuanshan Fuyuan public cemetery on the eve of Tomb-Sweeping Day. At right, Taipei City's pioneering Fude Life Memorial Park.

In November 2007, Eco-Friendly Memorial Garden was opened as a natural burial site on the grounds of the Dharma Drum Mountain World Center for Buddhist Education in northern Taipei County. The site only covers 100 ping (about 330 square meters), but the tremendous impact of its opening on the attitudes of people in Taiwan toward new burial practices has been out of all proportion to its size.

The memorial garden was established in compliance with the Taipei County Regulations Governing the Implementation of Ash Scatterings and Ash Burials, and is located in a bamboo grove on a gently sloping hillside above the banks of Caoyuan Creek. Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Foundation donated the site to the Taipei County Government after its completion, but remains responsible for daily upkeep.

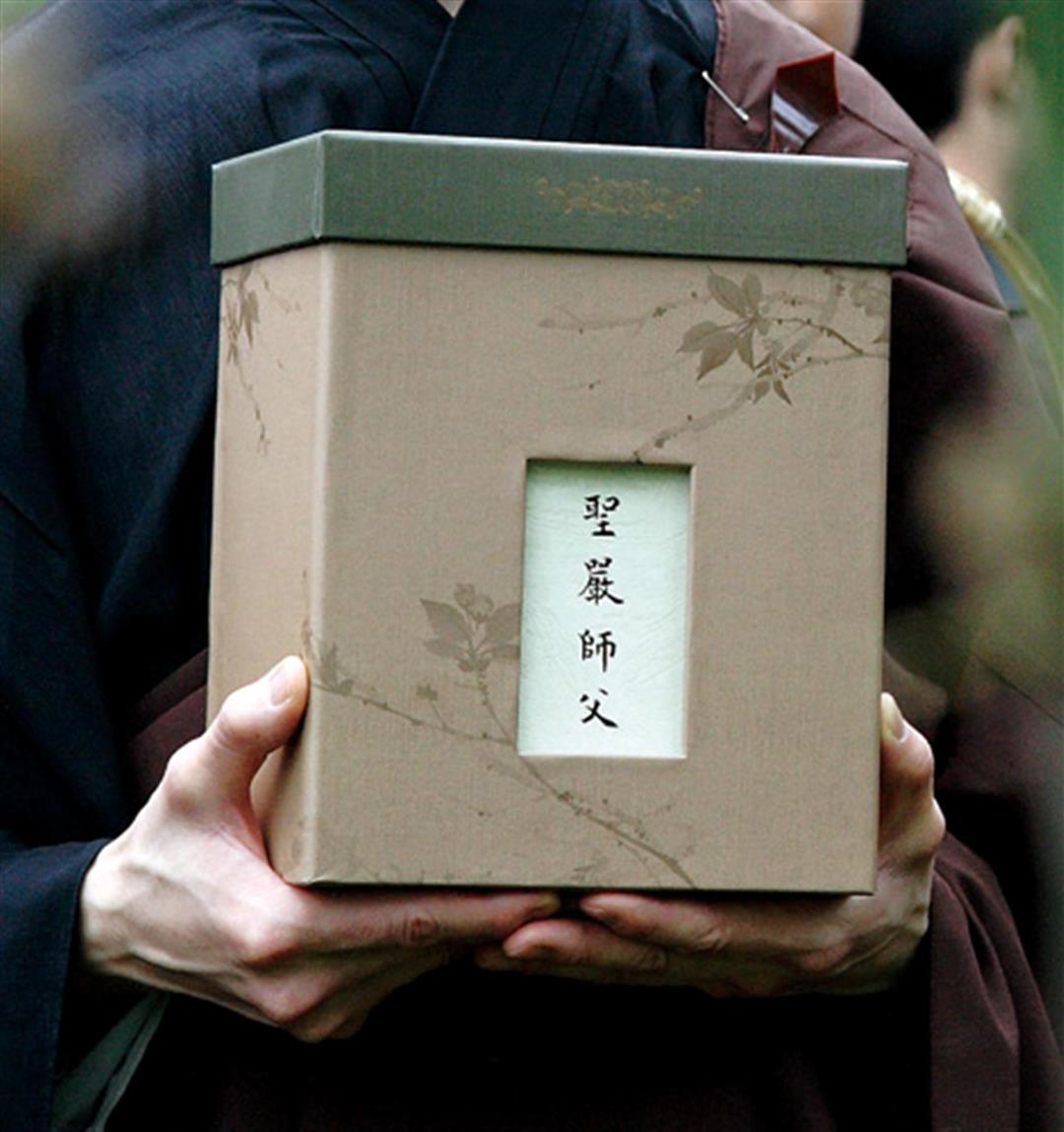

Master Guo Xuan, who is in charge of the memorial garden, explains that Master Sheng Yen always cared little about what should be done with his remains upon his death, and felt that the best solution would be to move on without leaving a trace behind.

"Master Sheng Yen once said that cremated ashes are connected in no way to a person's spiritual existence, but are simply the last remaining bit of carbon from one's body, and have no meaning whatsoever. The thing that is truly worth learning from and remembering is what a person taught by example."

In keeping with its principles of "equality, frugality, and simplicity," The Eco-Friendly Memorial Garden has never allowed anyone to erect a memorial tablet or name plaque to mark a burial site (even that of Master Sheng Yen), or to choose where in the park they would prefer to have the ashes buried, and during commemorative rites it does not allow people to leave flowers or to light candles or incense. What is even more unique, a person's ashes are placed in five separate bags and buried in five different spots. The site's keepers turn over the soil once every so often to accelerate the process of decomposition and, more importantly, to spur people to "get over their worldly attachments."

According to Master Guo Xuan, Dharma Drum's ultimate purpose in establishing the natural burial site was to create "a park dedicated to the art of life." After Master Sheng Yen passed away, the number of people inquiring about ash burials shot sharply upward (647 in 2009, versus 298 in 2008). Master Guo Xuan admits frankly: "The master is not even here. If people are hoping to share a final resting place with him, then they've failed to break free of their worldly attachments!"

At the Eco-Friendly Memorial Garden, volunteer staff comfort bereaved family members and ask them to listen to a briefing on how the burial will be carried out, before leading them on a 20-minute stroll along the banks of Caoyuan Creek (left). The final destination of the stroll is an ash burial site marked by a few young bamboo plants (right).

After Taipei City and Taipei County, the next to put on a vigorous push for natural burials was Yilan County. In July 2008, the Yuanshan Fuyuan public cemetery opened a 630-ping plot (roughly 2,080 square meters) for tree burials and ash scatterings, with burial locations scheduled for reuse on a three-year cycle. The plot is expected to have capacity for 400 tree burials and 600 ash scatterings in any one cycle.

Yuanshan Fuyuan is the first public cemetery in Taiwan to integrate the funeral and burial processes. The cemetery has undertaker facilities (freezer, cosmetizing room, casketing room, casket display room, and chapel), a crematory, a columbarium, and an earth burial graveyard, which means that the bereaved do not have to make another long trip to a separate graveyard upon conclusion of the funeral service. The landscaping at the site preserves the original lay of the land and a lot of the original trees to create a harmonious melding of hills and streams. The whole undertaking sets something of a standard for the creation of a park-like cemetery, and both government agencies and schools often make special field trips here.

Li Yongzhen, a senior technician at the Yilan County Mortuary Services Office, acknowledges that people in Yilan are more accepting of columbariums and cremation than they are of tree burials or ash scattering, but the Mortuary Services Office is confident that natural burials will one day become the mainstream.

The Yilan County Mortuary Services Office has taken various steps at Yuanshan Fuyuan to accommodate traditional sensibilities. Unlike other public cemeteries, for example, it allows the bereaved to set out commemorative tablets in a designated area and keep them there for two to four years before removing the tablets so more recently bereaved persons can use the space for their own tablets. In this manner, those grieving their loss can at first retain a sense of connection to the departed before gradually moving on and letting go.

Yuanshan Fuyuan intends to plant a lot more flowers and greenery to further accentuate the "park" aspect. It also has plans to allow families to adopt specific parts of the premises and carry out tree burials there, planting new saplings in such a manner as to coordinate with the afforestation work of the Council of Agriculture's Soil and Water Conservation Bureau.

Burial at sea is another option that has been promoted for a while now, but it hasn't caught on so well as tree burials or ash scattering.

In 2003, the Taipei City Government followed up on its tree burial efforts by taking the lead once again with burials at sea. It started collaborating from the third year with the Taipei County Government. The latter took over as principal administrator, and in the following year Taoyuan County joined in. Over a period of six years, however, a combined total of only 186 burials at sea have taken place.

The Taipei Mortuary Services Office explains that burials at sea have only been carried out once a year due to the high cost and the fact that there are not enough people opting for such burials to justify more frequent trips. They've taken place in May to take advantage of the gentle seas of springtime. About a week to 10 days ahead of time, the principal administrator notifies family members to deliver the remains of the departed to the Office. The remains are then ground to powder and placed in biodegradable burial boxes. On the day of the ceremony, all families take part in a joint commemorative service. As their boat heads out to sea, video montages showing vignettes of the lives of the departed (prepared by staff using items provided by the family members) are played on projection screens. The affair is simple but dignified.

In tree burial and ash scattering cemeteries the bereaved are generally not allowed to set up a commemorative tablet or a name plaque, but Yuanshan Fuyuan cemetery has settled on a middle path by providing a commemorative wall on which family members may have the name of the deceased inscribed. The name stays there for two to four years before being removed so more recently bereaved persons can use the space. This way the cemetery never reaches capacity and can continue being used, thus achieving the environmental sustainability that is central to the overall philosophy of natural burials.

Lee Jih-pin, general secretary of the Chinese Life and Death Academic Society, notes that funeral and interment rituals in Chinese society focus principally on the Confucian principles of filial piety and decorum, which for several thousand years has meant an emphasis on the importance of earth burials. Indeed, during several dynasties the practice of cremation was outlawed as an abomination against Confucian ideals. Taiwan, however, has succeeded in getting people to accept cremation over the past 30 years because both the government and the general public understand the acute scarcity of land here, and because cremation is considered a very good thing in Buddhist doctrine. Moreover, Far Eastern religions are accepting of diversity and have the flexibility to take up different funeral and burial practices in response to the changing times.

Natural burials, however, are still well outside the mainstream. Lee Jih-pin ticks off the following key reasons:

1. Strongly held traditional ways of thinking: People feel that tree burials, ash burials, ash scatterings, and burials at sea amount to ripping the body of the deceased to smithereens and depriving them of a final resting place, which runs completely counter to how the dead have traditionally been treated.

2. Need for a more gradual letting go: This point has made tree burials, ash burials, and ash scatterings more popular than burials at sea. People need a place where they can go to remember the departed. With burials in a park setting, even though there is no columbarium niche or commemorative tablet that they can come to, there is still a swathe of greenery or a park that they can associate with their loved ones. After a burial at sea, by contrast, once the remains have disappeared into the deep there is no way to revisit the spot and feel any connection between a particular location and the deceased. People find this unsettling.

3. Burials involve an entire family: Even where the departed has left a provision in his or her will requesting a natural burial, bereaved family members will not necessarily honor the request. Any change in such fundamental folkways is necessarily going to take a very long time. A stronger push from the authorities is needed, and education about death needs to be incorporated into the standard school curricula.

4. Funeral services providers have not been very enthusiastic about natural burials because they have a vested interest in the status quo and a poor understanding of natural burials.

At the Eco-Friendly Memorial Garden, volunteer staff comfort bereaved family members and ask them to listen to a briefing on how the burial will be carried out, before leading them on a 20-minute stroll along the banks of Caoyuan Creek (left). The final destination of the stroll is an ash burial site marked by a few young bamboo plants (right).

Huang Youzhi, who has spent many years involved in and writing on education about death, suggests that the best way to reform burial practices is to take it one person at a time. It is up to individuals to ask for a burial that is simple, environmentally friendly, and emotionally satisfying.

An old saying would seem very apropos: "Returning to the earth is not such a terrible thing; do we not then provide sustenance for the flowers?" Indeed, it does seem a fitting way to extend the fleeting life we have here, and makes for a heartfelt final good wish for the living world we leave behind.

Master Sheng Yen once said: "Death is an occasion for neither celebration nor grieving; rather, it is the occasion for a solemn Buddhist rite of passage." Shown at left is the ash burial ceremony that Dharma Drum Mountain carried out in February 2009 in keeping with the dying wish of Master Sheng Yen.

Before the ashes are buried, staff members ask the bereaved to observe one minute of silent remembrance, then divide the remains and place them into five separate burial holes before covering the holes back over with flower petals and earth. Another minute of silent remembrance then brings the ceremony to a close.

As life comes to an end, perhaps the best way to affirm its value is to choose the simplest and most direct return to the earth. Shown at left is the tree burial plot at Yuanshan Fuyuan public cemetery on the eve of Tomb-Sweeping Day. At right, Taipei City's pioneering Fude Life Memorial Park.

The moment we say goodbye could well be the beginning of a new life, for life and death are both part of the same never-ending cycle.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)