Pihsiang: Making the Electric Car Reality

Coral Lee / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Chris Nelson

March 2009

In 1983, Pihsiang Machinery Mfg. Co. started out in the countryside of Hsinchu County as a small farm machinery manufacturing plant. After their IPO 18 years later, they became the world's third-largest manufacturer of electric mobility scooters. And despite the global financial crisis, their revenues declined only slightly in 2008, from NT$1.8 billion to NT$1.6 billion, while maintaining a gross profit margin of over 30%. On top of this they launched a fully electric car, to the surprise of the world.

There is no shortage of tales of companies starting from scratch in Taiwan, but Pihsiang is one of a very few to become a global leader in key technologies, free of restriction from others. Company president Wu Pi-hsiang has a new dream, which is for Taiwan to become the first country to export fully electric cars.

In the minds of most people, the mention of electric cars conjures up notions of slow, short-ranged cars with short battery lives that are a long way from mass production, or hybrid vehicles that still use gasoline. But when I visited Pihsiang's plant in Xinfeng to test drive the electric Greenrunner car, I experienced the thrill of accelerating from zero to 50-60 kilometers per hour in under 20 seconds after pressing the ignition switch and stepping on the "gas." It can reach a top speed of 110 km/h, has a range of 220 km-about the distance from Taipei to Changhua-on a single charge, and the life of one battery is enough for 180,000 km, undermining most people's preconceptions about electric cars.

This car, specially designed for urban driving, sports a vividly colored, fashionable exterior, similar to the Smart Fortwo, and weighs 500 kilograms, much lighter than the average small car which tips the scales at 800 kg. Looking under the hood, you won't see the complex machinery and circuits of a traditional car; instead there are two big green plastic boxes (the two batteries). Where you'd ordinarily fill the gas tank, there is instead an electric socket. The cost of energy consumption is about NT$0.2 per kilometer (based on power costs in Taiwan), one 15th of that for 95-octane fuel, and the charging time varies according to charger and battery specs, as short as 1.5 hours or as long as seven or eight hours.

"The car's battery, electromechanical system and chassis structure are our design, and the exterior was designed in cooperation with the French auto manufacturer Microcar. We've done some minor pilot runs in Europe, and when launched under their brand, we estimate it'll sell for 16,000 [about NT$700,000] per car," says Wu, wearing a grey jacket and sporting curly hair, exuding confidence about the results of his R&D. After attending the Paris Motor Show, the world's largest auto show, in October 2008, Wu was contacted by numerous auto makers, such as the celebrated British firm Smith Electric Vehicles, to order his batteries, and French, German and American auto makers discussed joint development of electric cars with Pihsiang.

A tricycle featuring a lithium iron phosphate battery can be used without worry on upward slopes due to its high power output. It has sensitive pedaling sensors, making cycling easier and less laborious than on other electric bicycles in the market.

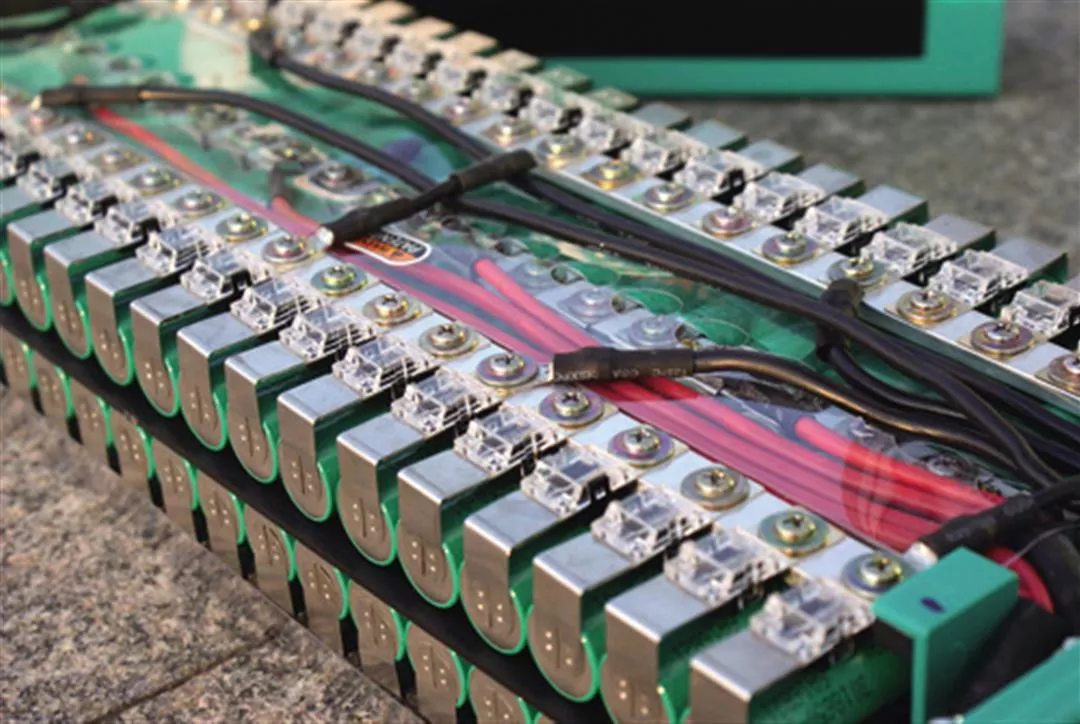

Super lithium battery

Wu, the soul of the company's technological R&D, explains that the key technology of the electric car is in the battery. Unlike the batteries used in other electric vehicles, the lithium iron phosphate battery developed by Pihsiang is made up of 2,000 small cells joined in series. If one of these cells fails, it will automatically "go to sleep," and not affect the performance of the other cells. This overcomes a problem traditional batteries have: if a cell fails, the car abruptly stops.

Moreover, in contrast to lithium cobalt oxide and lithium manganese oxide batteries, which may ignite or explode under high temperatures and whose power declines in elevated heat or strong sunlight, the lithium iron phosphate battery can withstand temperatures ranging from -45°C to 70°C. They have been tested in Europe's harshest climates, and even Alpine roads were no match for them. On top of this, the battery can be recharged 5000 times, six to ten times as many as other lithium batteries, and has a discharge efficiency eight to ten times better, making it highly economical. It has been hailed by scientific and environmental institutions in China, the US and Europe as the leading storage battery for the next 30 to 50 years.

Perhaps many will ask, "With electric vehicles in development for so long, and the world's major auto makers all doing R&D, what's the secret of Pihsiang's success?"

Looking back at over 20 years of Pihsiang's history of creating electric mobility scooters, electric wheelchairs and electric bicycles, as well as the founding of its subsidiary Pihsiang Energy Technology Co. (which specializes in producing batteries), Pihsiang has focused on both batteries and vehicles. Throughout, R&D innovation has consistently been the essence of Pihsiang's corporate culture, and is the locus of its competitiveness.

Pihsiang's four-wheeled mobility scooter is safe and simple to operate. Depending on speed and shock absorption, it is priced between NT$30,000 and NT$70,000, and has a range of 10-plus to over 30 km.

The ordeals of a pioneer

Tracing back to the grueling start of their enterprise, Wu's wife and company general manager Chiang Ching-ming says that Pihsiang has had a trying history.

Way back in 1971, Wu started up a farm machinery company. Sharp-minded and inventive, Wu, a graduate in agricultural mechanical engineering of the Pingtung Institute of Agriculture (now the National Pingtung University of Science and Technology), developed tillers, harvesters, and a wagon made specially for mountain slopes, favored by farmers who would approach him waving cash in their hands. His wagon earned him the Top Ten Outstanding Young Persons Award in 1978. But after over a decade of company growth, friends and relatives who served as nominal shareholders transferred Wu's shareholdings into their own names while he was overseas, and Wu left, dejected and penniless, to start over.

After a period of depression, he and his wife decided to start a new business. They raised NT$3 million from various sources, located a 50-square-meter prefab to serve as an office, and started afresh with a 1000-square-meter asbestos-tiled factory, some second-hand equipment, and a handful of employees.

At first, they continued to make farm machinery, but they knew deep down that agriculture was a declining industry and that they needed to develop more forward-looking products. "At that time we already had two-day weekends, because there wasn't that much work to do. But my husband worked 15 hours a day all year long and spent weekends developing products," says Chiang. Over the years they developed dozens of electric vehicles for different applications, including multi-purpose all-terrain vehicles, electric truck cabs, electric postal carts and more, before finally focusing on mobility scooters and electric wheelchairs.

"Earlier we found that many elderly people had problems walking, and they were scared of going outside without some kind of aid. So we started making three-wheeled electric mobility scooters," says Chiang. The sudden success of Pihsiang's four-wheeled mobility scooter stemmed from a chance event: at that time, due to a spinal swelling, Wu himself was driving around on a three-wheeled scooter he had modified himself, and the scooter fell over. He came up with the idea of a four-wheeled scooter as a means of improving driving stability.

Besides being used for cars, Pihsiang's lithium iron phosphate battery has a range of applications including consumer electronics, uninterruptible power supplies, hand tools, robots and medical equipment.

The harder the better

Back when he was doing farm vehicle R&D, it would take at most several weeks to finish a project. But this time, as he tried to add just one more wheel to an electric mobility scooter, he was, to his surprise, unable to finish the task even after spending several months on it. "Four-wheeled electric vehicles are not dissimilar in structure and operation from a car, but the design process was much more difficult because a mobility scooter isn't even one-third the size of a car," Wu explains.

Seeing her husband cooped up in the workshop all day, Chiang couldn't help but lose her temper one day: "You don't even care when dealers come here, and I don't understand the technology. Do we really want to keep this business going?" Wu replied, "Please give me more time! This four-wheeled scooter is complicated, but if it works, we'll be rich!"

At last, after two years, Wu finished the world's first four-wheeled electric mobility scooter, and in 1989 he secured patents in the US and Europe, showcasing it under the trademark Shoprider at an international medical supplies exhibition in Atlanta that year.

Weighing between 40 and 50 kg, the Shoprider offered simple operation, with two buttons for moving forward and backward, and the capacity to turn 360 degrees on the spot. It could even be operated with one hand. On one charge it could go 20 km, and it could be disassembled without tools in under a minute for easy transport. The key feature was the stability of its directional control; it was safer than three-wheeled scooters, yet no less maneuverable. It caused a sensation at the exhibition.

"But we didn't get a single order," says Chiang. They wanted to first test the waters of the market to see if it was worthwhile to carry on. Wu once again entered his workshop to continue his experiments, receiving more patents, while also investigating market demand and gathering information on competitors. It was the third year by the time he quoted a price.

"That year, Taiwan was still an OEM base for Japanese companies, but it didn't have the ability to develop products independently," Chiang remembers. Taiwanese products were not well regarded in international circles: the mere mark of "Made in Taiwan" caused a significant drop in price. To keep his painstakingly developed product from being considered second rate, Pihsiang exhibited it without selling it, putting the company at an advantage by looking before leaping. Once-haughty dealers vied for Pihsiang's business in droves. In the third year they finally decided to offer price quotes in Europe, where demand for quality was strict, and tastes and profits ran high. Given that it was just a small factory of under 30 employees at that time, the company began manufacturing in small quantities.

After the 1989 launch of the world's first electric mobility scooter, Pihsiang has released new models annually. In 2005, orders poured in after the unveiling of the canopy-equipped Shoprider.

The Mercedes of scooters

"The first time they received our formal shipments, our customers were taken aback because the construction and quality were far better than the original samples," says a contented Chiang. When customers called to ask what was going on, the president would say, "Of course the official product is better than the sample!" The product itself, once launched, became Pihsiang's best advertisement. The Shoprider soon climbed up to be a leading brand in the European market, and not only became the first electric mobility scooter to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, but also became the object of imitation by competitors.

What delighted Wu and his wife most was that Shoprider became a big hit in Japan. After Pihsiang invented the four-wheel electric mobility scooter, nearly 20 Japanese companies, including Suzuki, Toyota, Honda and Sanyo, started imitating the product. Pihsiang nevertheless soon acquired a market share in Japan of over 10%, second only to Suzuki. "The Japanese always think very highly of themselves, and the primary clientele of electric mobility scooters, the elderly, are especially patriotic. For a product from Taiwan to receive such an endorsement is the result of years of work!"

As the domain of Shoprider grew, Pihsiang's revenues reached new heights year after year, earning profits of over 40%. In 2001, after the company's IPO, the stocks hit 12 daily upper price limits in a row, which, during the recessionary period after the bursting of the global Internet bubble, was nothing short of a miracle. "Every day, investors and legal personnel came to our company to make inquiries," Chiang recalls. They didn't understand how a tiny, barely known company or such a modest mobility scooter could rake in such a profit.

This three-wheeled electric vehicle is easy to use and loaded with functionality, and is equipped with a removable battery box.

A culture of pragmatism

If we say that R&D nut Wu is the dynamo behind the company's creativity, then Chiang is the company's helmsperson. Their perfect match is the secret of Pihsiang's profitability. To pool its resources, Pihsiang subcontracts everything but its core technologies, key components, quality control and assembly, and oversees its operations with a sound computer management system.

Chiang remembers how, when they started their computerized time management system in 1995, many employees were quite opposed to it, but she was clear that this was a path that had to be taken. The more they delayed, the greater the obstacles would become. Under Chiang's stewardship, the company finished installing its enterprise resource planning (ERP) system 10 years ago, integrating the company's manufacturing procedures, product design, automated storage system, shipping and receiving barcode management and so forth, which greatly boosted operating efficiency.

"Lots of people asked me: with such high revenues, why would we want to go public?" says Chiang, responding that issuing stocks was not for raising funds but for the international arena, to let others know that Shoprider is a Taiwanese brand.

Surely, if we look at the development of successful companies, we find that the driving force behind their growth is not profit, but the achievement of an ideal.

More than four decades ago, when Wu was in high school, he saw a farmer carrying a large box of tangerines on his back. When the contents of the box spilled onto the ground, Wu vowed to himself, "I will make a vehicle to help these people." Twenty-plus years ago he noticed an increasing number of elderly people limping along with canes in their hands, and he thought, "I want to build a mobility scooter to help them go farther." A dozen or so years ago, he was inspired once again after seeing how research in Europe had shown that pollution from lead-acid batteries could make land infertile and was highly carcinogenic. "I must invent a clean battery," he thought.

Pihsiang Energy Technology Co. was founded in 2005, officially bringing Wu's business into the field of battery development for electric vehicles. Competitors were skeptical, but he forged ahead as he had done with his four-wheeled scooter.

Under the Greenrunner's hood, you won't see the engine or complex machinery of the traditional car; instead there are two large batteries. On one charge, it can travel 220 km, reaching a top speed of 110 km/h. As for battery life, the batteries will serve the car for 180,000 km.

The first clean battery

"Research papers and lab experiments showed that the three raw materials of lithium, iron and phosphorus that form the basis of triphyllite are able to discharge electricity. But no one in the world knew how to mass produce it," Wu explains. Each step in the manufacturing process from powdered raw material to finished batteries is highly involved. First, Wu bought a Taiwanese battery factory, and began trying applying sintering technologies to different mixes of the raw material powders. After thousands of trials, he found that iron ions suspended in carbon can become active generators of electricity, and could finally begin mass production.

The battery manufacturing process also took nearly two years of trials, and in 2007 they finally succeeded in developing an environmentally friendly battery that's free of lead contamination risk, won't ignite or explode, has a long life, and can discharge a high electric current. As a result, the company received official licensing of Hydro-Quebec, holder of a material patent, to manufacture, use and sell lithium iron phosphate batteries for various applications, as well as an exclusive right of use in the manufacture and sales of electric motorcycles, bicycles, wheelchairs and electric mobility scooters.

"Currently, no Japanese companies have successfully produced the lithium iron phosphate battery. There are two American companies that claim they already have this battery technology, but they are unable to mass produce them reliably," says Chiang. Pihsiang has already created the world's best such battery; unfortunately, they have yet to strike it big in promotion. In 2008, investor extraordinaire Warren Buffett looked favorably on the potential of the mainland Chinese company BYD in the car battery field, buying US$230 million worth of its shares, considered a major coup by mainland China. "But he didn't know that Pihsiang's car battery far surpasses that of BYD," says Chiang indignantly.

In preparation for the future trend of electric vehicle production by small companies, Wu has designed several chassis and electromechanical system modules, which he will license to domestic and overseas auto makers.

Hold on to that dream

Seeing Detroit's Big Three auto makers decline from their heyday of yore, Wu predicts that the electric cars of the future will become the province of small manufacturers, with each region developing electric cars with auto bodies, tires and motors that vary according to local environment and culture. Pihsiang has designed several chassis structures and electromechanical modules, and has applied for patents, with plans to cooperate with interested auto makers through licensing agreements.

Indeed, at the Paris Motor Show last October, the French automaker Microcar's electric car technology and batteries were manufactured by Pihsiang. And with major auto makers as yet unable to release fully electric cars due to limited battery technology, Pihsiang alone occupies a powerful position in global battery technology, with auto makers lining up to discus business deals with them.

To Wu, the toil of many years of R&D has once again paid off. But he would prefer that Taiwan would one day produce outstanding fully electric cars, rather than partnering with overseas companies. If Taiwanese auto makers are interested in developing electric cars, "I'm very willing to help them fulfill this dream," says Wu with sincerity.

In the past, mobility scooters were mostly used by handicapped individuals, but more recently they are being commonly used by the elderly just as a way of getting around.

At last year's Paris Motor Show, the Microcar was the only fully electric car on display. Its key technologies were its battery and electromechanical system, which were developed by Pihsiang. Here, Wu poses with a French model.

Wu heads R&D, while his wife Chiang Ching-ming is in charge of management. Together they complement each other naturally. Shown here are Wu and Chiang in the 1980s driving a dune buggy they developed.

From electric mobility scooters (bottom right) to lithium iron phosphate batteries and electric vehicles, each product launch of Pihsiang causes a sensation. Pictured here is company president Wu Pi-hsiang and his fully electric Greenrunner vehicle, which he designed and developed himself.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)