Johnson Health Tech:Pulling Its Own Weight

Kaya Huang / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Phil Newell

February 2007

It takes a seedling 30 years to grow into a big tree. Similarly, Johnson Health Tech Company, which sprouted up as a traditional industrial firm in Taichung's Taya Township, has, through quiet and steady tending over three decades, become an enormous organism, producing its own branches and flowers, making the transition from an OEM manufacturer to a name-brand company that sells products it develops itself. Today, Johnson's operational map extends to seven countries including the US, Japan, China, and several European nations; its products are sold in more than 70 lands; it employs nearly 7000 people; and it is the world's fifth largest manufacturer of sports and fitness equipment--and the premier such firm in all of Asia.

In 2006, Johnson for the first time entered the ranks of the top ten Taiwan international brands as listed by the Taiwan External Trade Development Council. There are currently four international labels under the group, with total revenues of US$300 million. Moreover, for ten years straight the composite growth of the firm has exceeded 35% each year, or five times the growth rate of the world leader Icon. Johnson has not only made history in itself, but is also a superb template for the transformation of traditional Taiwanese OEM manufacturers into global brand names of their own.

"What you see in front of you is the Central Mountain Range, and a little farther off to the right you can see the peak of Mt. Hsueh, while on the left there is Mt. Yu," says Peter Lo, chairman of the board of the Johnson Health Tech Company, as we gaze at the nearly boundless view from the windows of his 1000-square-meter office on the fifth floor of the corporate headquarters. His voice is strong and steady despite his advanced age. Not far off is the site of the Taichung Science-Based Industrial Park, where construction work is frantically going forward on semiconductor plants for which ground has only just recently been broken.

The Peter Lo of 30 years ago, a country boy so poor that he once had to pawn his watch just to buy some steamed buns to assuage his hunger, never dreamed that three decades down the road he would be the head of a world-famous corporation.

Building on the success of Vision Fitness, in 1999 Johnson established the Horizon Fitness label and sales company in the US. It focuses on the mass market, offering products that place as much emphasis on aesthetics as on function.

Poverty-driven

It is 1945, and Taiwan's immediate postwar economy is in a shambles. Peter Lo, the son of a poor family from a small village in Chungpu Township, Chiayi County, is forced to face up to the pressures of daily life by the one gift that fate has bestowed upon him--his poverty.

When he was small, this farm boy always wore nothing but short pants, summer and winter, and went about barefoot, carrying his books wrapped up in a piece of cloth as he walked each day to the Tingliu Primary School. In summer, the intense tropical sun would make the rocky road so hot that it was almost impossible to walk on it, but he had no choice. He recalls, "This experience made a tremendous impression on me. This is just the way the road of life is, and you've got to grit your teeth and bear it, taking one step at a time."

He was a natural with the books, and advanced through school easily. But when it came time to move beyond the level of junior high school, rather than following the high school track toward university, because of his family's poverty he had no choice but to make his top choice a teacher-training vocational institute where there was no tuition and he would get room and board. When he tested into the institute, he received a prize of NT$500 from the parents' association at his middle school. He remembers with a laugh: "That was the first time I had ever had so much money at one time, and I went out and spent NT$420 of it on a watch!"

After graduating, Lo returned home to become an elementary-school teacher, taking care of a household of seven--including himself, his parents, and four younger brothers--on a salary of just NT$480 per month. It wasn't long before he concluded that this was no way to live, and that he would have to continue with his education if he wanted to improve the quality of life. So he spent his free time cramming and tested into the Department of Economics at Soochow University.

Testing into university, he had to quit his teaching job, and came north with nothing but the NT$5000 he had saved up. But unlike his classmates, he was not there just to be enrolled in university, but to find a new future for himself and his brothers, three of whom came north with him.

Yet, Lo at that time was himself a mere child of 19, and he had to take care of his younger brothers, so how was he going to make it? Lo recollects: "After passing the entrance exam, my first thoughts were about the problem of surviving daily life. If I worked as a private tutor, at the most I could make NT$300 a month, just enough to pay rent, but not enough for food and clothing. So we had to figure out some kind of business to do."

At that time the 18-year-old second brother in the family was doing his compulsory military service, so next in line was the 15-year-old "Younger Brother Two." Lo found him an apprenticeship at a shop that installed fluorescent lighting fixtures, earning a paltry NT$50 per month. Lo then asked YB Two, "How long will it take you to learn how to do installation yourself?" When the latter responded that it would take a month, Lo unsympathetically retorted, "That's not good enough: You'll have to master it in a week!"

A week later, his brother had learned how to assemble and install the lighting fixtures, so Lo then asked him how long it would take him to learn about suppliers, costs, and other information. YB Two's answer was the same--a month--but Lo again insisted that he complete the task in a week--which Two did! Two weeks later, using what money they had as their capital, they bought some materials and, with a three-wheeled pedal-cart as their truck, the brothers started their own business.

During the day 12-year-old Younger Brother Three pedaled the bicycle-cart, the 15-year-old handled assembly and installation, and Lo went door-to-door trying to sell people on fluorescent lights. At night, the four brothers (the youngest being only 6) would crowd into their room of about ten square meters and assemble parts into complete lighting fixtures. "And that's the way we lived day in and day out," says Peter Lo with wry amusement.

At one point, things got so bad that Lo ended up at a pawn shop near Taipei train station, walking around debating with himself what to do while running his hand over the precious watch on his wrist. Finally he decided to go in. He could have pawned the watch for NT$50, and bought 50 steamed buns. But to save on interest, he would never take more than NT$20, using only NT$10 to buy ten steamed buns, and going out the next day to sell more lighting fixtures, spending the last NT$10 on steamed buns if he didn't make any sales, then redeeming the watch whenever he could.

"The poor do not enjoy the privilege of being pessimistic. Those years of wandering poverty eventually became the foundation and motivation of starting and running my own company," says Lo lightly. It was only after he graduated from university and passed the civil service examination to become a customs officer that life for his family stabilized.

As modern people place increasing emphasis on health and fitness, gyms have competed to offer the most up-to-date facilities and equipment, driving strong growth in the fitness gear industry. The photo was taken at a Gymlux Fitness Club.

One of the ants

It may be inevitable that in the blood of each entrepreneur there is an ingredient called "restlessness." One day, Peter Lo just decided "You have to give yourself an opportunity to make something out of life," and he quit his job to go into business.

"Johnson started out as a two-person company," says Cindy Lo, now the company vice-chairman as well as being Lo's spouse. In those days, she would often spend the morning in the front room writing English letters of introduction to be mailed off to the US, after which she would head back to the kitchen at noon to cook. In half a year, this "two-person company" had mailed off three or four thousand letters to the States, spending almost all their savings on postage. Lo thinks back to those days and says, "At first I had no idea what I was doing, and I just took US phone books and mailed letters to everybody, claiming in each letter that 'I can do everything,' endlessly writing and endlessly mailing." Finally, after half a year, they got a response.

That order was "just in time." The winter of 1975 was a cold one, getting down to 10°C outside, but Lo was feeling warm inside. When he got that request worth only US$200, Lo responded without even thinking about it, "Yes, I can."

In fact, he didn't have the slightest inkling what that first order, priced at US$15 per kilogram, was all about. Indeed, he had never even seen the "donut-shaped iron ring" described in the order, and still less had he any idea of whether or not the deal would be profitable. It was only when he took the blueprint all over the place asking questions that he discovered that the product he was being asked to make was called a "dumbbell." But that to him was not important. He stresses that "first you've got to survive in order to have any value." Only if the company survived, with that first order as its foundation, would there be second and third opportunities.

Next he moved to ask for help from factories with manufacturing experience in this line. But the first guy he came across told him, "Even if you do a crude job, it will still be at least US$20 per kilogram." When he heard this, his mood hardened and he told himself, "I refuse to believe it!"

So, in the spirit of a teacher pursuing a question without being satisfied until he gets the right answer, he made inquiries at more firms. He discovered that the raw material for dumbbells was pig iron, and that pig iron was made from iron ore imported from Brazil. So he sat down and did the math: a kilo of raw material at NT$4.20, $1.20 for fuel, $6.20 for molding costs, $0.80 for polishing and finishing, plus more for drilling, coating, packaging.... If he did as much of the work as possible by himself, he figured that his costs would be US$8 per kilo, leaving US$7 in profit. Using an entirely improvised crude casting process, Johnson's first order for dumbbells from the US was thus produced and delivered, piece by piece, out of a rented former chicken coop.

That experience set Johnson off on the OEM path. Turning a profit in the first year, Lo bought land in Taichung (now the site of the Johnson global operations headquarters), built a casting plant, and began cooperating with the US firm Ivanko to produce weightlifting gear. Within three years, price advantage combined with the warrior-ant like power of the "Taiwanese-style SME" (small or medium enterprise), turned Johnson into the world's largest supplier of weightlifting equipment, accounting for half the global market.

It took Lo only three years to bring in to play the comparative advantage of the Taiwanese SME, but it took only two more years for the situation to change dramatically. In 1978, China initiated the policy of economic reform and began to play a major role as "factory to the world," offering low prices its competitors could not match. In addition, the technical barriers to entry for production of free weights are low. At that time Johnson's list price was US$40 per kilo, whereas Chinese firms were quoting US$20.

In order to survive, Lo had no choice but to transform. The shift from OEM to ODM (original design manufacturer) took Johnson a mere six months.

"Hey boss, what's this machine here? It's like a bicycle, but it's only got one wheel." It is now 1980, and Peter Lo has just brought back from the US Taiwan's first-ever exercycle, and, with its own workers still in a state of perplexity, Johnson plunges headlong into the field of exercise cycles, and moreover decides to shift to the ODM path, doing its own R&D. Orders from world leading companies like Universal, Tunturi, and Schwinn soon follow.

But the same regrettable events as before repeated themselves, and by 1995, global sports equipment manufacturing had entered a period of ferocious competition, with PRC firms proving to be strong at copying. Once again Johnson was facing a struggle for its corporate life.

Making a global brand

Responding to the collective state of emergency of Taiwan's SMEs, at that time the government began strongly promoting the development of brand names, and Peter Lo, facing his second transformation, had to face hard questions: "Should we lower our prices? Set up a factory in China? Head to the US to be closer to the market? Abandon the price wars and build a brand name as the foundation for future profits?"

Facing up to his fate, Lo realized that even if he packed up shop and turned his back on his homeland, if he didn't escape from the model of producing for other companies, the cutthroat price competition would never end. So he decided that Johnson would take its own products direct to the US market. With the US having the largest demand for sporting equipment in the world (accounting for two-thirds), Lo knew that "as long as I could break into the US market, other places would not be a problem." Thus did the embryo of a global identity take shape in Lo's mind.

A goodbye phone call from Nathan Pyles, general manager of Trek Fitness, one of Johnson's oldest clients, was the trigger that set Johnson off on the road of developing its own brand names.

"Tell your chairman to sell Trek Fitness to Johnson!" is what Lo responded to Pyles. Three days later, Trek Fitness' owner arrived in Taiwan, and asked for US$5 million. Lo sat quietly for a moment, and then his one-word response shattered the silence: "Free!" Lo told his counterparts that because by this time the equipment that Trek was selling had been patented by Johnson, neither Trek nor anyone else could sell or service the design. Ultimately, he acquired Trek for just US$100,000, setting Johnson on the path to brand-name independence.

But multinational mergers like the one Johnson was attempting all face a key test: blending into other cultures. If you are not careful, you could end up like Taiwan's giant cell-phone manufacturer BenQ, which acquired Siemens of Germany but ended up coming home with its wings clipped. How can companies from different lands be combined?

Peter Lo responded with what he calls his "hybridization theory." Taiwan's sand pear, he declares, is less than popular because the fruit is rough and fibrous. But the rootstock is very resilient, and if Japanese Shinseiki pear scions are grafted onto a Taiwanese sand pear rootstock, they can produce sweet and tender fruits. Similarly, Johnson had strong roots in manufacturing, R&D, and management, while Western countries excel in branding and marketing. Combine these business qualities and you will surely end up with a very fruitful partnership.

Another tactic that has helped is that, in terms of personnel management, Johnson always uses local managers for its branches and subsidiaries in other countries, seeking out professionals who understand the local market. The Taiwanese headquarters just handles support functions, rewards, and penalties.

"Only by adapting to each local culture can you have the most effective management," avers Lo. You have to create a model that encourages initiative, that enables these professional managers to produce their own results in their own way, and does not waste their energies on system problems like who to hire or fire, or how every penny is spent, so that they have no time to focus on their real jobs. With everything functioning properly, Johnson turned a profit its first year abroad, and has since enjoyed composite growth of 35% per year, surpassing its main competitors Nautilus (17%), Amer Sports (-2%), and Cybex (7%).

Vision Fitness was at one time the fitness products division of Trek Bicycle, which was itself once the world's largest maker of outdoor bicycles. Acquired by Johnson in 1996, Vision's product line is mainly sold to specialized sporting goods shops.

Competitive advantage

The thing that has really allowed the powerful tree that Johnson had become to branch out and flourish has been its corporate strategy of differential marketing. The market niche selected for a product and the success of branding have a tremendous impact in the sports equipment industry. The key to Johnson's success has been in its ability to coordinate marketing channels, branding, and manufacturing.

"Products have to conform to the local market. In the US, for example, they have to fit American tastes. If a product is designed in Taiwan, then the feeling will be different," says Lo. Only Americans can really understand the styles, dimensions, specifications, and colors that other Americans will like, whereas the Taiwan headquarters can do its part in providing corporate structure and actually producing the necessary software and hardware. This combination not only adapts to market demand, it is also cost efficient.

In terms of marketing, Johnson sells different brand names via different channels. For example, in the corporate department, whose main clients are health clubs, Johnson pushes the Matrix and Johnson brands. To shops that specialize in selling athletic equipment, the Vision label is used, while for department stores and other large retailers which cater to the general consumer, the main line is Horizon.

Target: World number one

Talking about the future, Peter Lo believes that Taiwan will be most competitive in the market for home-use fitness gear. However, while Taiwan is strong in machine design, its sporting goods are not distinctive enough when it comes to international branding. What they lack is refined overall design that can blend the technology into a product that fits unobtrusively into people's daily living environments.

"It's not hard to develop an international brand name, it's just that everybody thinks it is hard, and so they don't dare to take the first step," says Lo with concern. He advises, "Businessmen have to get it straight in their own heads exactly what they want. After all, when you are managing a company you have to be hard-headed and practical!"

"World Number One in 2008!" This slogan is prominently displayed on every floor of the Johnson office building, and on every department bulletin board. Beyond that, Lo has agreed with over 1000 employees to head to the Beijing Olympics in 2008 as the world's number-one company in this field. In fact, they've already begun reserving hotel rooms. Is this illusory hubris? Or well-deserved confidence? You should know the answer to that one by now.

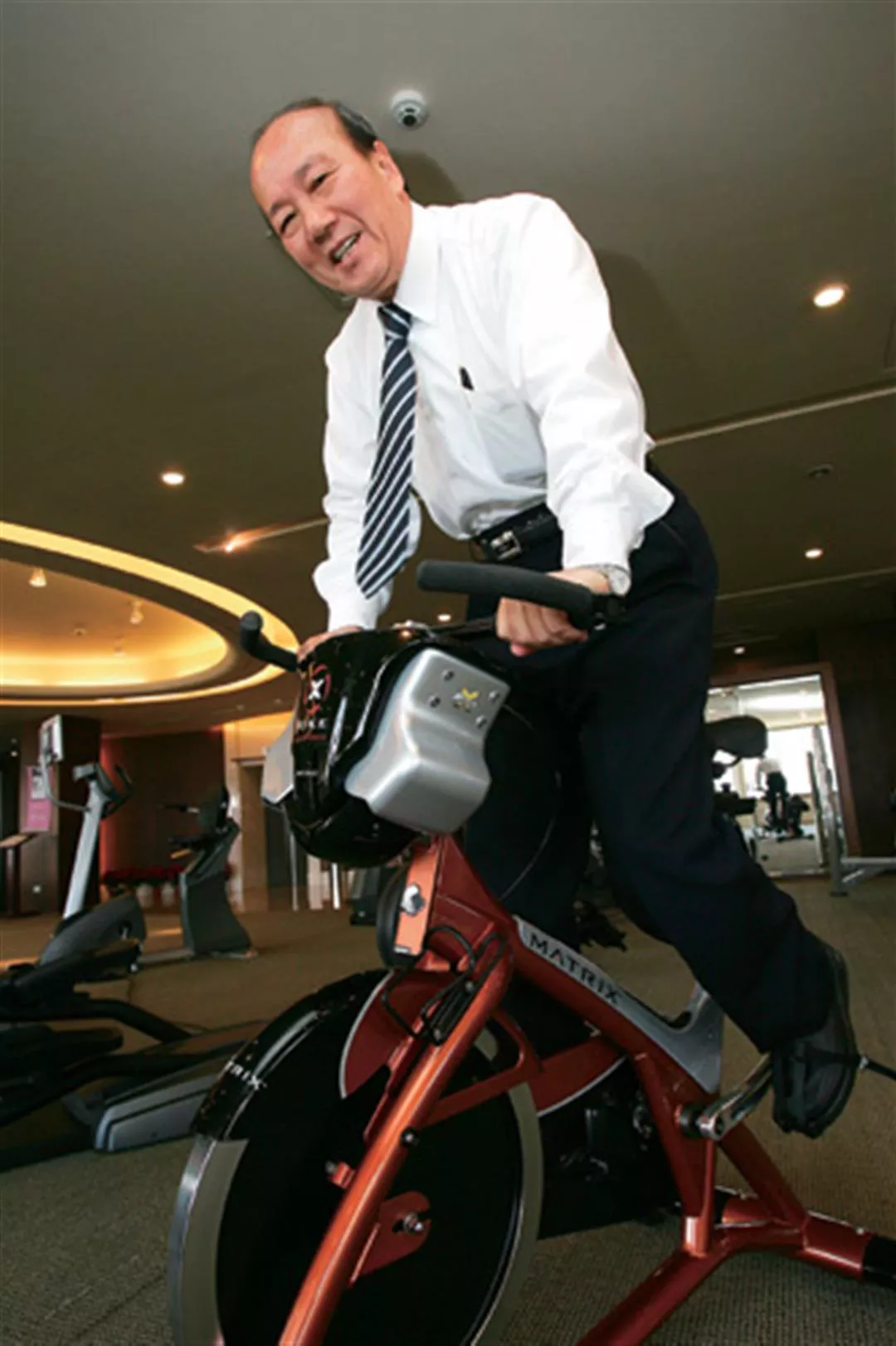

From the founding of their "two-person company" in 1975, Peter Lo and his better half Cindy Lo, have maintained a restrained and understated lifestyle. For three decades, each day has been the same: Up at 5:30, working out for an hour on a Johnson running machine, off to the company at 8:00, and a simple lunch at the office at noon; bedtime is at 10:30.

Peter Lo is leading his employees on a long-term quest that goes under the slogan "Call Me the World's Number One," creating a center around which they all can unite. The photo shows the product exhibition hall at Johnson's Taiwan headquarters.

From its days as an OEM manufacturer to its current status as a global brand name, Johnson Health Tech, under the leadership of Peter Lo, is a classic mighty-oak-from-a-tiny-acorn story from the ranks of Taiwan's small enterprises.

Goods in the Matrix product line are mainly made for the needs of high-end corporate gyms, health clubs, five-star hotels, office complexes, and hospital rehabilitation centers.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)