Doing Well by Doing Good--CSR in Taiwan

Coral Lee / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

May 2006

We're in an era when doing good is all the rage!

In 2005 Time magazine awarded its person of the year accolades to Microsoft founder Bill Gates and his wife Melinda for their work in improving conditions for the world's poor, and to rock star Bono, who likewise has thrown himself into public interest work. Businessmen in Taiwan were not to be outdone. Not long ago Chang Yung-fa, chairman of the Evergreen Group, pledged NT$2 billion to buy the KMT building for a foundation that will do international charity work. And in their daily lives people in Taiwan can see all around them still clearer evidence of local businesses working for the public good: The Shin Kong Group has contributed money to support abused children, and Taiwan Mobile has provided aid to the victims of natural disasters, while UMC and the Hon Hai Group have provided a "children's aid plan" to benefit disadvantaged children.

But is public interest work of this ilk, which throws money at mending holes in the social safety net or adds funds to well-known charitable endeavors, enough? Today, when multinational corporations are spreading their tentacles throughout the world, gaining influence and financial and administrative power that often surpasses governments, there are growing calls for "corporate social responsibility," or CSR. CSR works on three main fronts--economic, environmental and social--calling for corporations to utterly transform themselves: top to bottom, inside and out, in both image and substance. The goal is to make corporations "profitable ethical entities" that "benefit themselves, others, and the environment" and that take greater responsibility for world peace, prosperity and sustainable development. In response to this new world trend, Taiwanese corporations have a lot of work to do!

What impact has CSR had in Taiwan? Let's look at some recent news items.

At the start of April the government finally responded to the long-simmering controversy about electromagnetic radiation from mobile phone base stations. It announced a plan to remove about one-third of these stations--some 10,000. Though not yet a firm policy, the proposal drew different opinions from different quarters. The environmental groups that had sparked the brouhaha supported the government's move but declared it insufficient. They argued that the government should have issued safety standards for electromagnetic radiation. The wireless service providers argued that by shutting down too many base stations, the measure would force phones to give off stronger radiation in order to transmit a clear signal. This was more detrimental to users, they argued. Experts, meanwhile, suggested that the danger posed by electromagnetic radiation wasn't in fact very substantial.

"At first wireless service providers didn't communicate enough with communities," says Niven Huang, secretary general of Business Council for Sustainable Development in Taiwan. "Later, they didn't show up to explain their research data and policies, or teach users about proper use and safety." Huang notes these controversies often occur because businesses focus on profits and ignore social responsibility.

An adherent to the concept of "green competitiveness," Delta Electronics integrates environmentalism into its management strategies. They've discovered that developing energy conservation technology and products has both created business opportunities and earned the company a good reputation. The photo shows solar panels at Delta's Neihu headquarters.

From outside in

"The fact is that although Taiwan has been talking about CSR for years, we're still stuck at a very superficial level," says Huang, a longtime observer of corporate development trends. He explains that Taiwan corporations often regard CSR as being the same as public interest work, and they take such steps as establishing foundations, supporting cultural activities, adopting parks, and aiding the disadvantaged. But Huang emphasizes that these "outward" public interest activities are but one link in the CSR chain. A true CSR campaign has to tackle a corporation's core spirit, so that CSR becomes "internal" policy that encompasses management operations.

"In Taiwan there isn't enough understanding about CSR, and usually it's done only part way," notes Daniel Chu, senior executive vice president of the GreTai Securities Market. "Because it's not turned into policy and institutionalized, it's hard to put thoroughly into practice." Chu, who has worked with the OECD for several years to promote good corporate governance among listed companies, explains that CSR has had a big impact abroad. Taiwan ignores this trend at its own peril.

Huang describes how, when Walt Cheng took over as chairman and president of Dupont Taiwan, Dupont's vice-chairman, via videoconferencing, offered his congratulations from headquarters. Rather than talking about competition and profits, his whole speech revolved around the corporation's concern for people and its environmental responsibility. His broadminded outlook made a big impression on listeners.

CSR is not just for advanced nations; it extends to developing countries as well. At the request of UN general secretary Kofi Annan, PRC corporations have one after another joined the United Nations Global Compact, for which they pledge to work toward progress in human rights, labor, the environment and other areas. Huang, who has recently returned to Taiwan from Beijing, saw how the CEOs of PRC firms were talking about CSR with confidence. This quick change has him worried about Taiwanese corporate prospects.

Globalization is the main force behind this international trend.

More than sympathy for the poor

Large corporations have gained the most from globalization, and they also have the most to lose from protests against it. In the age of global competition, when there is a widening gap between rich and poor, who can help the poor shake off poverty, find jobs and improve the quality of their lives? From the perspective of the UN and many international organizations, government does bear some responsibility, but many nations suffer from growing budget deficits and low administrative efficiency. Multinational corporations, on the other hand, wield great financial and administrative power and often play a role that eclipses government's. As a result, various standards, such as the OECD "Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises" and the UN Global Compact call for corporations to act responsibly and use their power to change the world for the better.

In her book The Silent Takeover: Global Capitalism and the Death of Democracy, British economist Noreena Hertz says that corporations are giving more and more serious consideration to social and environmental issues out of concern for not only the disadvantaged, but also the bottom line. Take Nike, which suffered consumer boycotts based on critiques of its labor practices. Its sales figures and reputation took hits, and it had to pay out damages.

Yet how do these international trends relate to Taiwan?

"Taiwan has 18 of the world's 1000 largest companies, and in terms of overseas investments it ranks somewhere from 17th to 20th," notes Huang. "It's also the 15th-largest trading nation." Taiwan's showing in these various economic indexes places it among the "20% of wealthy nations that enjoy 80% of global wealth." Yet, because Taiwan's government has limited international recognition, when the UN and other bodies discuss the issue, Taiwan isn't included. As a result, we are insensitive to CSR concerns. "There is a large gap between the responsibility Taiwanese firms assume on issues of international poverty and disease and the expectations the world has for Taiwan," Huang says.

What is the basic spirit of CSR? Close examination of multinationals regarded as having outstanding records on CSR reveals that they show concern for their own employees, their suppliers, their customers, and "stakeholders" (such as community residents). Their concern extends more broadly to the global environment and general human welfare.

Cheng Loong uses recycled paper for its paper boxes. Well known for its emphasis on the environment and worker safety, it garnered Asia-wide orders from Nike--much to its own surprise.

Ethics as a core value

Hewlett-Packard, which employs more than 150,000 people in some 170 nations, puts concern for "ethics" and "public interest" in all levels of its operations. It could well be described as a model for CSR.

"We consider the environmental impact from product development, through purchasing and production to recycling," says Andy Lai, general manager of enterprise marketing and solutions for HP Taiwan. He cites the example of design. Unlike production or recycling, which already have many international standards and rules to follow, "design relies upon one's conscience." In recent years HP has put a lot of money into researching how to use cornhusks as biodegradable copier casing, or developing screwless, snap-together casing. These are examples of design that reflects environmental concerns. At the same time, HP uses the same green standards for all its global operations; it doesn't lower its own standards because of laxer regulations in third-world nations.

With regard to materials used, companies must be environmentally responsible. With regard to people and behavior, they have to behave ethically. Based on the requirements of the technology and Internet industries, the human right that HP cares about most, both for its staffers and its customers, is the right to privacy. HP does not discriminate based on sex, religion, ethnic background, marital status, or disability. "Ability is the most important criterion," says Lai. Although racial prejudice is less of an issue in Asia, sexual inequality is still a problem. HP has for many years been concerned with implementing sexual equality at work. It has created a mentoring system for its women employees and has also set standards for promoting a certain ratio of women executives. It also requires its suppliers to adopt similar standards.

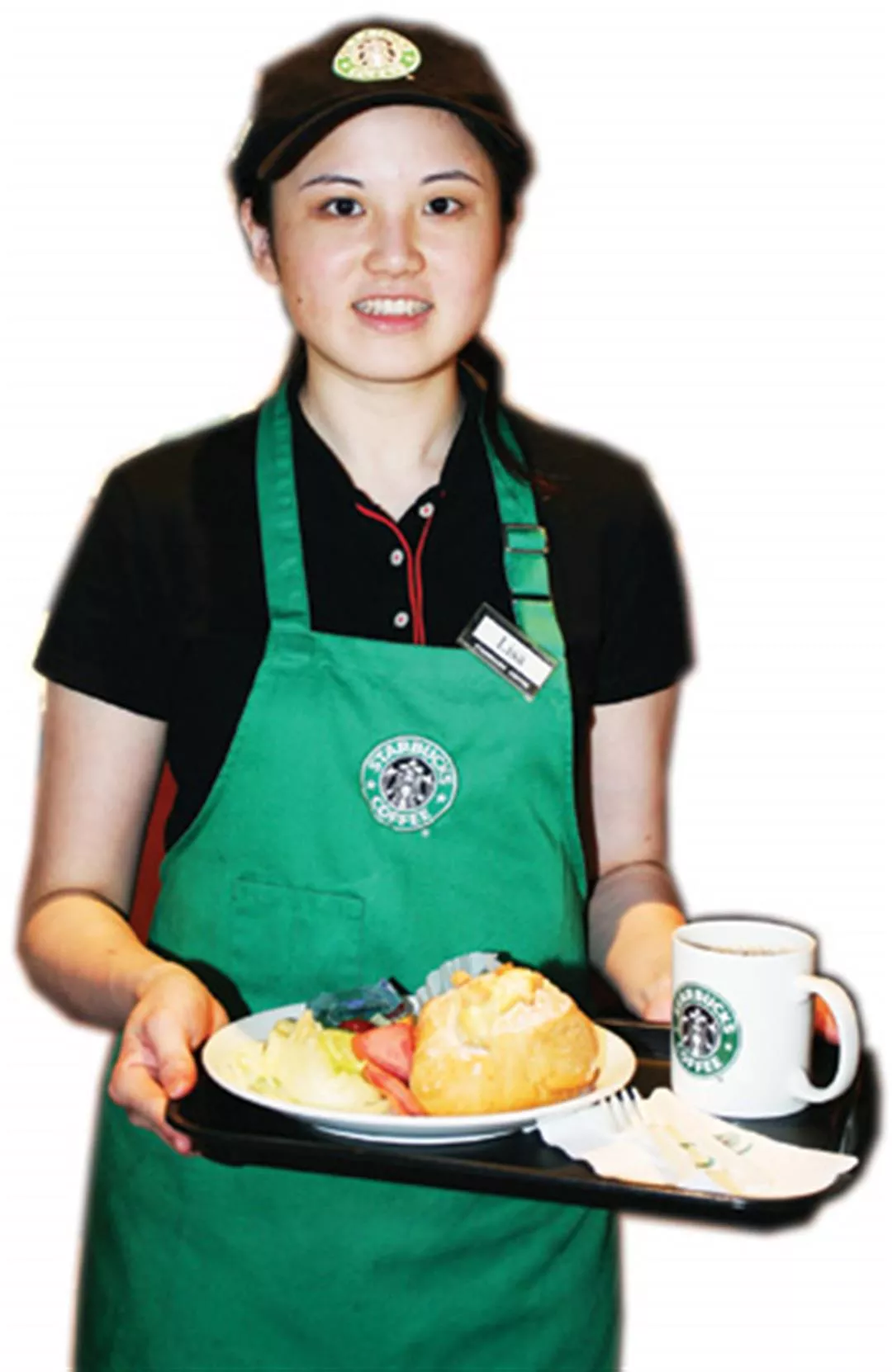

Modern businesses must first move consumers' hearts before cultivating customer loyalty. Starbucks, which stresses respect for its workers and fair treatment of its coffee plantation suppliers, is one such example.

Sweatshops

The responsibility that corporations have for so-called "stakeholders" is perhaps one of the grayest areas of CSR. What with differences between professions, as well as cultural and national differences, and differences in size of corporations, there are so many aspects to consider here.

Take responsibility toward employees. Hi-tech companies are known for their creative and technological content. They stress equality, flexibility and autonomy, as opposed to traditional manufacturers that stress salary and labor conditions. Especially when labor costs are a key to profits, this poses serious challenges.

In the 1990s, when the labor rights movement was rising, Nike, the global athletics apparel company, became a lightning rod for labor group complaints, perhaps because of its high visibility. From 1991 to 1993, the British and American media repeatedly issued reports about Nike's exploitative labor practices. "Nikes that sell for US$150 are made by Indonesian women laborers earning 58 cents a day." These reports claimed that laborers were working without adequate protection next to hot molds, surrounded by glue and paint fumes. These conditions posed health and safety risks and were unethical.

They prompted consumer and human rights groups to launch a global boycott as part of an anti-sweatshop movement. Nike complained that reports attacking it were often slanted, mentioning only the salary given to workers in training, intentionally ignoring bonuses, and neglecting to mention that the starting salary of 2800 Rupiah per month was about five times what local farmers made. But no matter how Nike tried to explain, they couldn't smooth over consumer dissatisfaction. Although the workers were actually employed by Nike's suppliers, Nike was universally condemned. Brand-name companies have the power to select their suppliers, it was argued, and therefore should accept responsibility for their suppliers' labor practices.

"In 1997 Nike's CEO finally made a public apology," recounts Professor Pan Shih-wei of the Graduate Institute of Labor Studies at Chinese Culture University. Nike developed a code of conduct based on eight measures of international labor standards, including reasonable wages, working hours, workplace safety, and workers' freedom to organize. They required all their suppliers worldwide to abide by the code, and they designed a monitoring system. As a result, other major companies in the same field, such as Reebok and Adidas, quickly followed suit. It revolutionized the whole supply chain.

Cheng Loong uses recycled paper for its paper boxes. Well known for its emphasis on the environment and worker safety, it garnered Asia-wide orders from Nike--much to its own surprise.

Responsibility and trust

Companies that don't treat workers well will pay a steep cost, but if corporate executives are proactive in taking good care of workers, won't that require greater expenditures and hurt profits? Wouldn't that be unfair to shareholders?

Starbucks, which has more than 9000 branches worldwide and over 90,000 employees, has used comprehensive benefits to create high growth year after year. In the process it has destroyed the myth that businesses can't do well by doing good.

Employees aren't disposable parts on an assembly line, writes Howard Schultz, Starbucks CEO, in his book Pour Your Heart into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time, in explaining his conception of how to treat employees. Originally from a poor family in Brooklyn, Schultz saw how his father toiled all his life yet never obtained his employer's respect. He spent decade after decade lacking job security and feeling insecure. Not long after Schultz took over Starbucks, his father passed away. It was then that Schultz decided that treating his employees with the utmost honesty was key, and that his highest objective would be to allow all of his workers to become shareholders. Because the company was losing money at the time, he first convinced the board to reward employees with a comprehensive benefits plan, which was offered, without precedent, to two-thirds of the workforce.

When Starbucks' financial situation stabilized, he convinced the board once again to offer the employees shares in the company. These measures, revolutionary for the restaurant industry, ended up cultivating an extremely loyal workforce. They resulted in low personnel turnover, which saved a lot in training costs. And the employees gratefully responded in kind: To save the company money, some employees would take evening flights for business trips, and at work they would propose money-saving measures and offer concrete ideas about how to increase revenue. Most importantly, they did their utmost to provide enthusiastic service that resulted in highly loyal customers. Financial analysts believe that this is Starbucks' true strong suit, one of the keys to its rapid expansion.

In addition to its relations with employees, Starbucks' relationship to the coffee plantations that supply its coffee is also enlightening. In Faith and Fortune: The Quiet Revolution to Reform American Business, Marc Gunther, a senior writer for Fortune magazine, explains that Starbucks realized that its fate was tied to its suppliers. Consequently, with the help of Conservation International, it publicly announced in 2001 a set of principles for purchasing coffee: Starbucks would spend top dollar for coffee from plantations that protected soil and water quality and biodiversity, so as to protect the environment of the tropics and ensure the quality of Starbucks coffee. At the same time it required coffee plantations to meet labor, human rights and safety standards. These standards were more comprehensive than the "fair trade" standards seen in recent years. Starbucks provided a broader range of protections, because it deeply understood that the coffee plantations were part of its future.

At the same time, when the global price for coffee was collapsing, Starbucks was willing to pay above the market rate because it didn't want to see coffee planters turn to growing coca leaves instead.

Schultz admits that managing a highly ethical company isn't easy. The outside world holds up a magnifying glass to their environmental principles and their treatment of coffee plantations. One has to spend a lot of time and money to deal with issues that competitors needn't concern themselves with. But it's a burden Starbucks bears because the company cares a lot about the opinions of consumers and staff, Schultz writes.

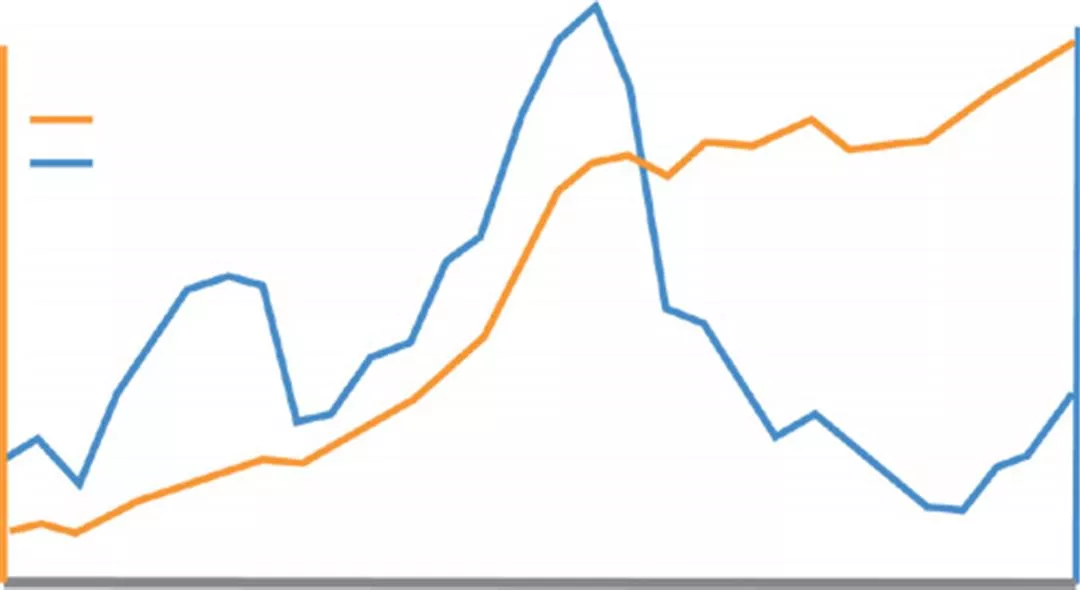

The experience of Starbucks and HP echoes the results of much research conducted over the past several years: Among the companies listed in the Standard & Poor's 500, superstars in their treatment of stakeholders have also had among the most outstanding performances. That's because when a company's management policies are merciful and just, it naturally builds trust that helps to shape high-quality management, and quality management is a leading indicator of outstanding economic performance.

Modern businesses must first move consumers' hearts before cultivating customer loyalty. Starbucks, which stresses respect for its workers and fair treatment of its coffee plantation suppliers, is one such example.

Opportunities for green companies

"Ben and Jerry's is a socially responsible ice cream." "The Body Shop is building an ethical network of retail stores." Or how about Google's motto: "Don't be evil" Many companies in Europe and the US already make ethics and social responsibility a major theme of their operations. Taken as a whole, CSR in Taiwan may not compare. But if you look at its component parts, it is not without worthwhile aspects. Taiwan's manufacturing industry, for instance, has a fairly deep understanding of environmental issues that has been noted by various foreign manufacturers.

Take, for instance, the "RoHS" (Restriction of Hazardous Substances) directive issued by the European Union." RoHS restricts the importation to Europe of electrical and electronic products containing six toxins, including lead, mercury, and cadmium. But Taiwan's Delta Electronics was already meeting those standards five years ago. R.T. Tsai, Delta's general manager for business development, explains that in 2000 Delta invested in equipment for lead-free soldering and adjusted its internal management procedures, to produce motherboards and various other products more cleanly.

"As a result of this technology, Delta unexpectedly acquired orders from Sony," says Tsai. Back then one part in Sony PS2 game consoles--a power rectifier--was tested as having too high a lead content to enter Europe, and all the consoles were shipped back. The losses to Sony were more than 100 million. Later, Sony looked for a new supplier and discovered that Delta had the technology. It placed an order for more than 1 million of the parts.

"At the time there was no competition for this product, so Sony gave us one order after another. The result was that we helped ourselves and helped them," recounts Tsai.

There is no lack of stories of how traditional industry unexpectedly gained orders by putting an emphasis on environmental and social responsibility. Take Cheng Loong, a company that uses recycled paper to make various kinds of paper boxes. Apart from the environmental concept of the product itself, the company is known in the industry for emphasizing green production, worker safety, and energy conservation. At the end of the 1990s, after much negative publicity about "sweatshops," Nike looked for new suppliers and discovered that Cheng Loong's products very much matched its SHAPE criteria (safety, health, attitude, people, and environment). In 1999 it began to give all of its shoebox orders in Asia to Cheng Loong.

"Back then Taiwan was in the midst of an economic downturn. All our competitors had to tighten their belts," recalls Li Teng-ming, Cheng Loong's environmental safety manager. "We never expected to suddenly obtain such a large order. Our revenues grew rapidly." Due to shipping costs, they had never even considered that paper boxes could be exported. The opportunity resulted in the company in recent years reaping excellent revenue from its global operations.

A group of volunteers came to Yangmingshan to turn an abandoned quarry into a beautiful wetland. In the future it will become an outdoor environmental classroom. Through this "working holiday" sponsored by Bayer, a global chemicals company based in Germany, the natural environment and people both benefit.

Another peaceful revolution

Many CSR seeds likewise have sprouted in various Taiwan fields: At the peak of the exodus of bicycle plants from Taiwan in 2002, Giant, the world's largest bicycle manufacturer, deeply understood the need to raise the level of the industry here. Therefore it worked with 11 other bicycle manufacturers, including competitor Merida, to share a "low-volume, high diversity" production line model, so as to raise management standards and avoid cutthroat price competition. The effort allowed the bicycle industry to keep its roots in Taiwan. For its more than 200 suppliers on the mainland, Giant also provides a free training plan, broadmindedly raising the level of the industry throughout the region. These are examples of how CSR treats stakeholders well and creates benefits for all.

"This is a peaceful revolution," says Marc Gunther of Fortune. More and more large corporations believe "doing good is the best management method." Early this year, at a book launch party for Responsibility and Profit, Taiwan CEOs one after another demonstrated their corporate citizenship ethos: "Sincerity and trustworthiness are our moral principles," said Taiwan Semiconductor, a leader in its field. "Walking the long walk with a heavy load," is what computer and consumer electronics company BenQ expects of itself. Wonderland Nursery Goods, a maker of baby strollers and car seats, says it stresses corporate responsibility by using the English phrase "doing well by doing good."

Doing good must indeed have its rewards. This seemingly old-fashioned value is guiding companies from around the world through the challenges of the 21st century.

On 22 April 2006--Earth Day--Hewlett-Packard Taiwan began a two-month campaign to encourage consumers to get into the habit of recycling printer ink and toner cartridges.

Do the cosmetics you use contain lead and mercury? When consumers raise health and safety concerns, they may well lose their trust in a company unless it provides comprehensive and transparent information in a timely manner.

As corporations look around for good investment opportunities, they shouldn't neglect concern for the local community. The photo shows Nien Hsing's Chentex plant in Nicaragua, which is a major global supplier of denim. Because of the company's unfamiliarity with local customs, the factory was a lightning rod for labor movement attacks in recent years. The experience should serve as a wake-up call to Taiwanese companies.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)