In recent years novelist Huang Chun-ming hasn't been writing many novels and instead has thrown his energy into creating children's books. As far as he is concerned, this isn't a sudden turn of events. A good storyteller, Huang in days past produced such children's programs on television as "Little Dumb Dumb." He believes that writing novels and creating children's literature are both pursuits of an ideal. It's just that the audience is different. He used to be writing for adults. Now he's writing for children.

In his view, "Modern adults are already beyond saving." Since his own children have already grown up, he says he's had no choice but "to go love other people's children." But he makes it clear that he won't cast aside novels, which he describes as like a wife to him.

Q: Most readers think of you as a writer of novels with local color and a rural backdrop. Now that you're writing for youngsters, have you found that there is a fundamental shift in switching from writing novels to writing children's books?

Writing for the ideal

Q: It's not much different. In artistic creation there are two routes: one is art for art's sake, and the other is art for humanity's sake.

In the Chinese literary tradition, we've taken the latter route, taking concern about society as a starting point. As far back as The Book of Poetry Chinese literature has described the life of common people. Realism can be described as the main current in Chinese literary tradition.

Chinese writers always hope that their work will have a direct impact on social progress. During the period of the Three Kingdoms, Tsao Pi said "Literature is what shapes the nation." And it was still that way at the beginning of the Republic of China, when Liang Chi-chao wrote an essay, "The Theory of Using Novels to Save the Country" in which he argued that foreign countries were stronger than China because their fiction was better, that literature invisibly leaves its imprint on people's thinking.

The writers of my era in Taiwan have a kind of romantic sentiment about the novel, always holding onto an attitude that "if they can write something, it will be of use to society."

In the past decade, Taiwan's economy has taken off. With the universality of television and changes in values, virtually no one reads novels anymore. Now books are all non-fiction, like those describing how to make a fortune playing the stock market. The best sellers are all telling you "how," but there are many fewer books of a contemplative nature telling you "why," getting to the roots of things.

The market reflects people's needs. Adults no longer need literature. What they want are short easily digestible essays, touching on the universe and life in just one page. In our current high-speed culture, it seems that you can get close to the mysteries of the universe and life, but in reality you're just cheating yourself.

The attitude of carrying great expectations about literature, of using literature to provide service to society is already changing greatly. Adults are mired in the evil ways--they're already beyond being saved. Why should I take my experience in writing and painting and waste it on adults who can't be saved anyway? And so I have turned my focus to children.

Saying I want to save children may sound grand, but I have little actual power at my command. But just because I have little power, that doesn't mean that I shouldn't try, or otherwise my power will have no way to combine with others.'

But I haven't completely given up on adults. I still want to write novels. To me writing novels is like a first wife--with me forever.

One needn't have so much knowledge

Q: Among the children's stories in your recent five volumes, in some of them you take a rural setting and infuse them with descriptions of local color, which to a certain degree reflects your nostalgic feelings, but they still come from the experience of a contemporary adult. For example, the books mention scarecrows, but very few city kids will have ever had an opportunity to see a scarecrow. It is removed from the realm of experience of children. Will this put them off?

A: This is a good question. While things like these aren't in the far distant past for the parents and may be of some value to keep in the memory, there may be some things that adults like and remember fondly that hold no interest for children. I remember when my child was still small, I took him to my hometown of Lotung. He complained, "Daddy, I want to go home." I said Lotung is home, and he said, "Lotung isn't my home, Taipei is." one's nostalgic values aren't necessarily correct; they can't be forced upon children.

Whether or not children's stories can be accepted by children and influence them requires a lot of assessment.

For example, the story of the tiger dressed in the guise of an old lady who bites a child's finger doesn't require a description of violence because the children have already been frightened. I'm not against violence in children's tales. We are cultivating children's ability to distinguish between good and evil. They shouldn't grow up in a "germ free incubator." They will certainly come in contact with these germs when they go out into the world. We should develop their resistance to disease.

Secondly, we can see that most children's stories have happy endings. But look at Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Match Girl." Though tragic, it is among the world's best stories.

This time I wrote a story about a hunchback child. After he died, his friends would become very sad whenever they thought of him because he had been so virtuous. I have used a theatrical method to show the value of life.

Some adults, however, think that we shouldn't make children face death. The fish and chicken that mother brings home from the market are also dead, and children ask, isn't it terrible that chickens' heads are chopped off. It's not that you can't speak of death to children, but it's that when you're speaking of it, you've got to be sympathetic and have feelings for others. But you've got to be instructive in the way you approach it.

I think that the selection of materials is very important, but I can't give you a mechanistic, legalistic standard.

Stories have got to have imagination

Q: Today's parents will buy books for their kids regardless of cost, and there is a great variety of children's books on the market. When you're creating for children, do you think about what kind of books are appropriate for them?

A: Imagination is extremely important for children because they don't have ample life experience. Especially for pre-school children, the pictures are more important than the words. The art work in children's books isn't merely drawings that accompany the text. Rather pictures are the language of children. They let kids enter into the story, giving them space for imagination and participation.

Let me give you an example. I remember when I was six or seven and there was a big earthquake in Lotung. My grandmother told me that earthquakes happened when the earth bull was shaking his shoulders. At that time, there weren't cranes and bull dozers around yet, and it seemed perfectly reasonable that there was a bull in the earth. It was just a question of how big. Did it sleep at night or not? I kept turning these questions over in my brain.

When my older cousin, who had been away at high school, came home, I asked him, "Was there an earthquake in Ilan?" He said there was, and so I said, "Wow, that bull is really big!" because I was thinking it's a long way from Lotung to Ilan--if there was an earthquake along that whole stretch, it must be one big bull. My cousin explained to me how earthquakes happen, that they're caused by the falling down of the geological strata, by the colliding of plates and the exploding of volcanoes. But this was all so abstract. What were the geological strata? How did they fall? Depressed, I asked my grandmother why she lied to me. She asked back, "Then why are there earthquakes?" and I had no response.

Then Granny said, "Earthquakes happen when the earth bull is moving. As for the rest of that stuff that your cousin said, you'll understand that later when you go to school." And I was happy once again.

And the explanation of the earth bull didn't have any effect on how I later studied the scientific reasons for earthquakes.

Today parents are eagerly trying to force precise scientific knowledge upon their children. The fact of the matter is that "the knowledge of imagination" is also extremely important for children. A good children's story should give children ample space for imagining as well as be interesting.

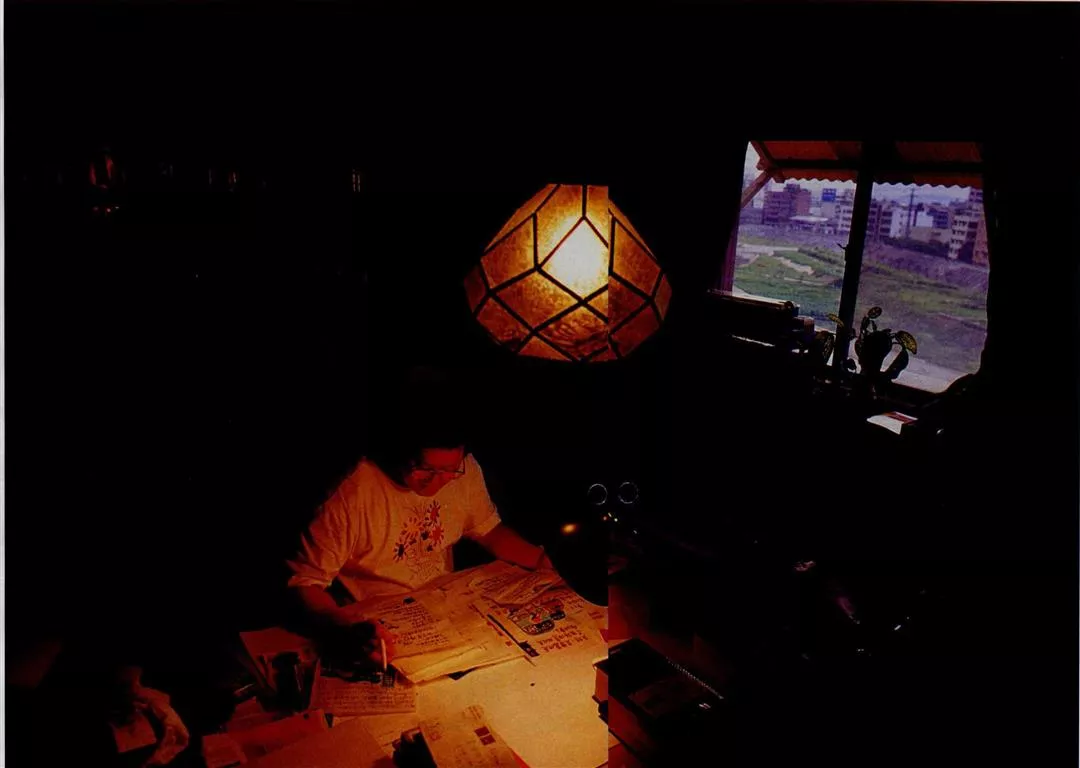

A solitary lamp and a closet full of books; It is here where Hu Chun-ming creates his children's books.

Writing with one's own special character

Q: You once said that "children's tales aren't the monopoly of foreigners." Besides being created by ourselves, is the content of Chinese children's stories any different?

A: Besides things from daily life, our cultural inheritance is the best material for stories. For example, I took Tao Yuan-ming's The Story of the Peach Flower Spring and rewrote it through the eyes of a child. In the story, "Little Li Isn't a Big Liar, " Little Li comes back from the Peach Flower Garden to tell people that there is such a place. But no one can find it. Because he is a child, the county magistrate doesn't punish him, but other people all say that he is a liar. Little Li says, "Don't call me that. I didn't lie. I know what it looks like. Now I'm going to plant peach trees to create a place like it." Changing it in this way, I have created another Utopia, and I believe that Tao Yuan-ming would approve.

Or take the story "The Foolish Old Man Moves the Mountain." A modern version could be written of it.

It may be that these stories are just child's play, but I think of child's play as a serious matter. Now there are too many people who start writing stories for children only after they fail writing books for adults. It shouldn't be like this.

Previously, when everybody was reading translated novels people said that this represented a kind of xenophilia, and so they would call for realism in literature, for a native literature, for a literature of the land. But the truth is that children need these ethnic tales even more. Now most of the children's stories are from abroad and aim to impart knowledge, but what we really lack are creative, imaginative books. But no one is making a call for this. I want to go down this road. I want to be a model for others.

Q: You have worked as a planner in an ad agency and as an elementary school teacher. And you have even sold boxed lunches. Some people say that because you have this variety of experiences, your work is closer to the real nature of people. What do you think about this?

A: The experiences that you can really form ideas from probably come mostly after you're 20. Within the limits of one life, sampling different walks of life may indeed give you more experience than other people. But literature engraves an image of an age, a group or a person. If it is written well, it can create a projection of an individual's life. This is because people have many things in common. Experience can be classified. To the creator, it doesn't make much difference if it's direct experience or indirect experience.

Establishing the authority of the classics

Q: Could you give today's parents some practical suggestions about buying children's books?

A: It's hard to make just one standard. There are in fact a great number of current children's books, and they are dazzlingly packaged. Adults can first make some direct judgments about a book. Will children like the book? Is the content imaginative? If you as an adult think it's good, it probably shouldn't be too bad. Some books, while printed well and illustrated attractively, are dull, leaving no room for the imagination and providing no food for thought for the minds of young readers. And parents should try to read more children's books.

Most people ought to establish what are the classics for themselves. There are a great many books that appear in a historical setting, such as books by Mark Twain or Gabriel Garcia Marquez that already transcend time and space. They've been around for 200 or 300 years but they haven't been forgotten and are still being translated. If you read more of these books, you'll establish your own authority and standards.

The creators and the readers can thus both put demands on themselves to see whether or not there is a standard close to being authoritative. The more contact you have with something, the more you will have your own way of looking at it.

[Picture Caption]

p.92

A solitary lamp and a closet full of books; It is here where Huang Chun-ming creates his children's books.

p.95

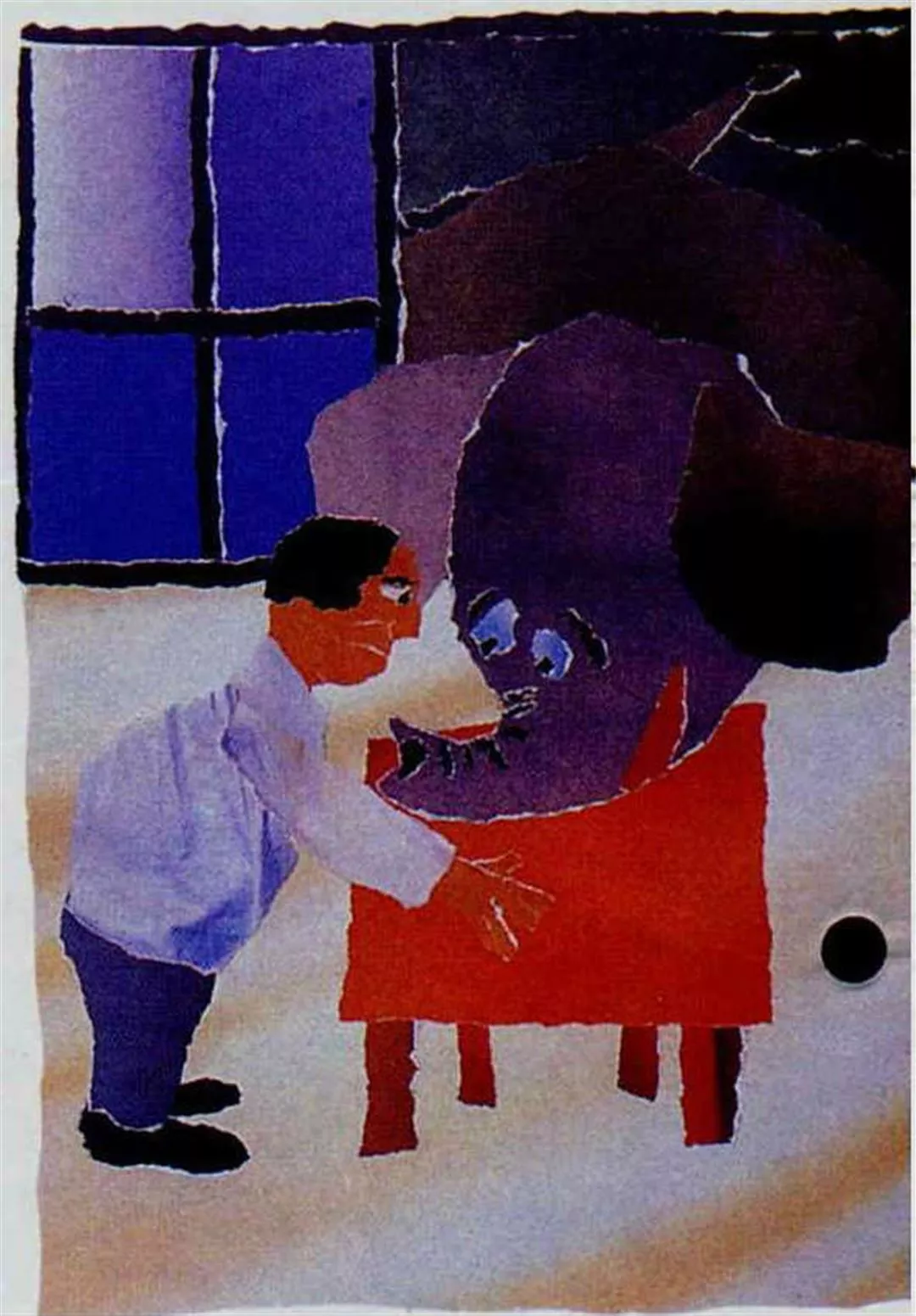

When his children were still small, Huang was off in America. He would illustrate the letters sent home to his children, which told of his everyday experiences in a distant land.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)