Happy in a Supporting Role--Stage Costume Designer Lin Ching-ju

Kuo Li-chuan / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

March 2007

Two years ago the College of Dance at Taipei National University of the Arts staged an innovative production of The Afternoon of a Faun by the Russian "dance god" Vaslav Nijinsky. Vaslav's octogenarian daughter Tamara Nijinisky traveled from the US to attend. Afterwards, the full house offered a thunderous ovation to the adapting choreographer, director, orchestral conductor and all the performers. To express her gratitude, Nijinsky then excitedly shook the hand of Lin Ching-ju, the costume designer.

Winner of the tenth National Award for the Arts in dance, Lin has been diligently toiling behind the scenes for more than 20 years, working on more than 100 productions, which range from dance, to theater, music, traditional Chinese Opera, and children's theater. The range of productions she has worked on is extremely broad, and she takes great care with each.

"Every stage production should be performed as an integrated artistic whole," says Lin calmly as she peruses design sketches that fill her room. "The clothes ought to add value to the performance rather than steal the spotlight." Before there was any conception in Taiwan of "theater costume design," this rail-thin woman was grabbing hold of professional skills, crafting costumes one stitch at a time with great thought and workmanship, and intently pulling Taiwan costume design to an international level. The image of her obscured amid piles of fabrics is one of the most moving sights in the world of Taiwan theater.

Lin Ching-ju was born in Taipei in 1952. Her father was a reporter at Kung Lun Pao, which back then was one of Taiwan's most important newspapers. Although he had a regular job, the paper had precarious finances, so he often couldn't collect his salary, and the burden of providing for the family's six mouths fell to Lin's mother. Exhibiting an aptitude for the arts at a young age, Lin would often lead her friends in making paper cutout dolls and imitating the Huangmei Opera Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai. She'd devise a scenario and direct her friends in acting it out.

A vain junior-high student, she would save up her lunch money, buy fabric and bring it to a seamstress, who would make a dress to her specifications. Although it was an era when one might be labeled a "bad girl" for wearing unusual clothes, Lin's mother tolerated her daughter's non-conformity. Rebellious in spirit, Lin didn't care about the odd looks she got and happily wore her own creations regardless of the attention they attracted on the street.

For over 20 years Lin has constantly challenged herself professionally as she has raised theatrical costume design in Taiwan to an international level.

A cover up with ribbons

When she was studying business at Chih-kwang Vocational High School in Yungho, Lin designed a set of performance clothes for her friend Wu Han, a pianist who was studying at Kuang Jen Middle School. She worked just for the fun of it, but once the design genie was out of the bottle, it wasn't going back in.

Lin entered the professional ranks of theatrical costume design in 1978. Dancer Huang Li-hsun had just returned from Austria and was planning a modern dance production of Chang E and Hou Yi. Perhaps her passion for costume design clouded her judgment, but Lin took on the whole job of designing and making the costumes despite having never studied dressmaking or taken a design class.

When she was sketching the designs, inspiration flowed and she made the most of her creativity. But when it came to actually sewing the outfits together, she was at a total loss. So she went to the seamstress who had helped make her own clothes. The seamstress had to burn the midnight oil to help Lin finish. Lacking previous experience with theater, Lin was in for a shock when she took the costumes to the rehearsal space and saw them under the stage lights: "The feel and coloration were totally different from what I had imagined!" Anxiously, she ran home to do the costumes over.

Dress rehearsal offered an even bigger lesson: With the strong stage lights bearing down, the pink costume of Chang E became a sickly white, and Hou Yi's blue looked dirty. But the performance was imminent, so adding some ribbons to obscure the costumes was all they could do. Nevertheless, Lin didn't lose her nerve. Instead, she and the seamstress formed Chiyili, Taiwan's first company specializing in theatrical design, the following year.

After going into business, Lin began to learn sewing skills from her seamstress partner. Every day, she stood at the seamstress's side and learned things in the proper order, from pattern making to cutting and sewing. She laughs about her lack of facility with numbers, saying that even a calculator can't save her since she presses the wrong keys. After ten years of struggling with numbers and frequently miscalculating, she came up with her own ergonomic pattern making method, which creates tight-fitting clothes very exactly.

Sensitive to the importance of costume designers with professional skills, Lin has for many years taken on apprentices so as to cultivate talent for Taiwan's theater world.

The decked-out dozen

In 1980, when Cloud Gate Dance Theatre went on its first tour of Europe, the dancer Chen Wei-cheng introduced her to Lin Hwai-min. "My greatest stroke of fortune in this life was to meet Lin Hwai-min," Lin Ching-ju says. "He brought me into the world of art, and also encouraged me to cultivate a perfectionist's attitude about my work." With Lin Hwai-min's demands on quality, Lin Ching-ju barely slept or ate for seven or eight days to create the costumes for Cloud Gate's 1982 production of Nirvana. She would stand beside the 220 oC dye pot trying to create just the right unique shade of glittery blue.

"I didn't realize the dye had been damaged by humidity, and I was determined to create the exact hues I wanted. I kept adjusting the color and trying different dyes, and adding glacial acetic acid as a fixer." When the big job was done, she just laid down her head and fell into a deep sleep. The workers felt that something was wrong and tried to wake her. They discovered that she had breathed in excessive quantities of the dye fixing agent, which contained strong acidic toxins, which had damaged the lining of her oesophagus. They rushed her to the hospital emergency room.

As someone who would sacrifice a week of sleep for the job, she would certainly not permit a delay in the performance, so she lay in the ambulance, thinking, "Oh no, I won't have time to finish the costumes." From time to time she would ponder: "Which stage of the dyeing process caused the problem?" It drove Lin's mother, who had previously always been very supportive, to her wits' end.

In 1983 the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre put on an important production of Dream of the Red Chamber. For the 12 jin chai (refined young women, or literally "golden hairpins") of the Daguan Garden compound, she designed beautiful brocaded capes. These also proved a challenge.

As she gazes at the sketches for those capes that she made 24 years ago, Lin herself seems dreamily ensconced in some corner of the compound. The play used flowers to represent the women, with each flower's color representing the corresponding character's personality and fate. For instance, Lin used a white hibiscus for Lin Daiyu and a red peony for Xue Baochai. To make clothes that would be suitable for the dance stage, she dyed nearly 300 fabric samples, from which she chose 12.

She and the painter Chiang An (the older sister of Chiang Hsun) separately designed floral patterns for the capes. They drew each pattern onto an A4 sheet of paper, and then knelt on the ground to transpose it via a grid onto an eight-by-16-foot sheet. "Oddly, we didn't feel it was tiring work at the time," she exclaims.

After the pattern was enlarged, Lin took dyed fabric and spread carbon paper on top. Lying on the floor, she then copied the pattern line by line. Once the lines of the embroidery were apparent, she contracted out the work of the embroidery, which was done by machine. Then Lin sewed the pieces together to complete the costumes.

The "12 hairpins" resembled 12 flowers competing in beauty. As the 12 women dancers moved about the stage in these capes, the grace, poise and unique bearing of these daughters of a high-ranking official were amply reflected in their flower-god appearances. The production was praised as "a world of flowers and colors." Those unique, exquisitely embroidered capes were the most beautiful and classical elements of that production.

Sacrificing for art

After the training she got in dyes from working on Nirvana and Dream of the Red Chamber, Lin, who could "capture any color she wanted," grew ill due to her long-term exposure to the lead in dyes. At one point, she wasted away to only 36 kilos. She'd wake up in the morning and cough blood, which had a lead count eight times normal. Blemishes from the lead were visible on her face and neck. The frequent pain in her knees was hard to bear. She still breaks out in rashes from time to time.

When asked why she risked her health for the sake of theater costumes, she responds: "I don't know. Once I dived in, I couldn't pull myself out!" In addition to Cloud Gate, she also worked with the Taipei Dance Circle, Lanling Theater Workshop, Contemporary Legend Theater, Taigu Tales Dance Theatre, Ping-Fong Acting Troupe and so forth. Almost every major theater group of the era asked this goddess of costume design to work with them.

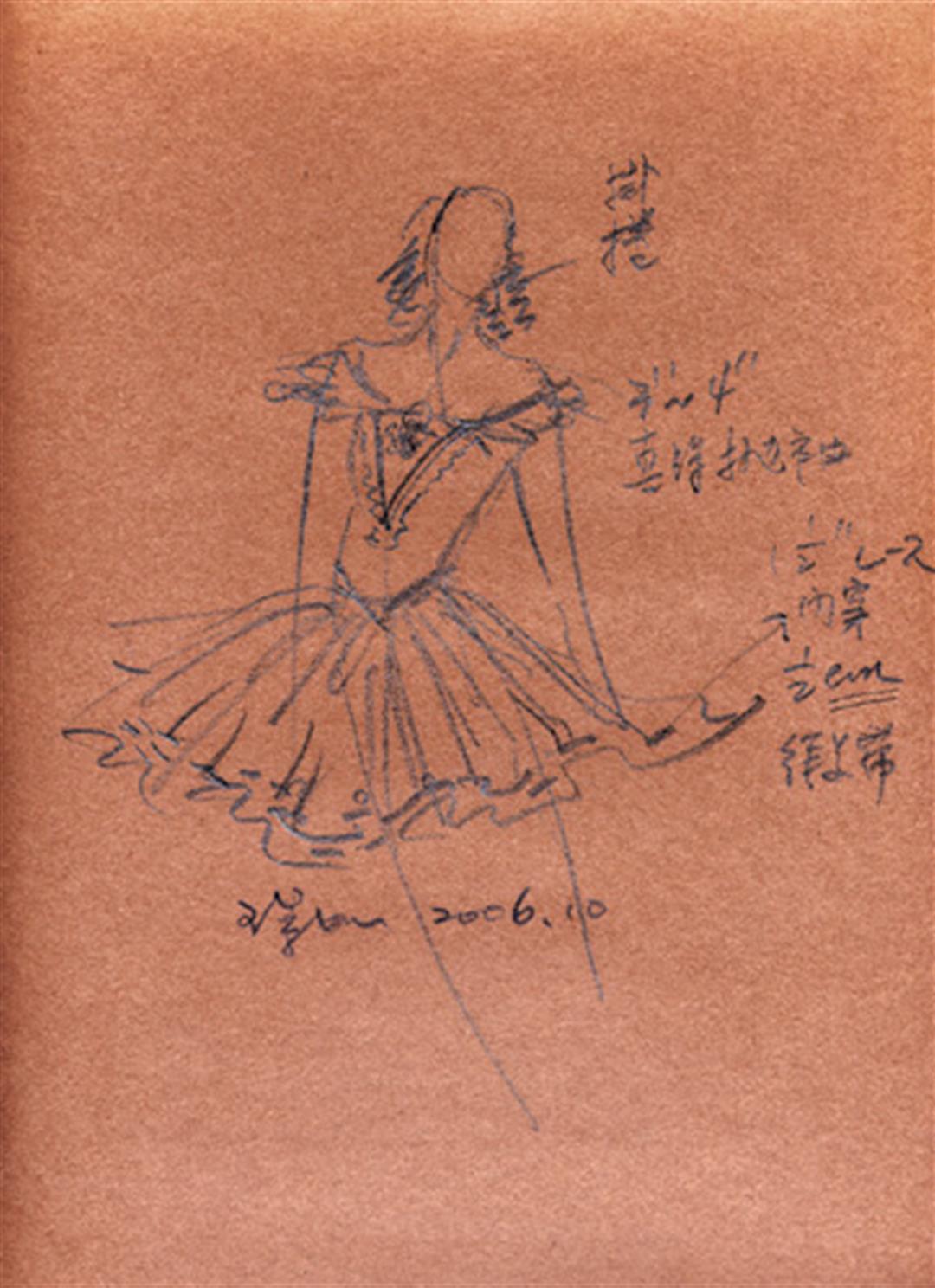

Lin's preparatory sketches of theater costumes.

Commercial ups and downs

The 1980s were also the heyday of Taiwan's dinner-club shows, and Lin's company took a two-track approach, producing clothing both for professional theater companies and dinner-club shows. She designed fancy outfits for singers such as Liu Wen-cheng, Tsui Tai-ching and Chang Li-min. She even designed the costume that variety-show host Chang Hsiao-yen used in her popular "Yibaila" spacewoman skit.

Lin's workshop was located on Taipei's Jen-ai Road, near Air Force headquarters. To cope with growing orders, they kept expanding. Some of the staff ended up focusing on making fancy costumes for theater and shows, and another group focused on researching and developing tight-fitting aerobics and dance clothing.

In those years, as her dinner club and aerobics business expanded, she was the very picture of a confident women entrepreneur directing her own business. But unexpectedly, the company manager embezzled funds, and her southern Taiwan distributor ended up copying her designs. By the time she uncovered these problems they had already seriously hurt her reputation and lowered her revenues.

When it rains, it pours, and just as the company was experiencing these management problems, faulty wiring in the aerobic and dance clothing department on the third floor of her studio caused a fire. Sketches accumulated over many years, along with finished clothing and bolts of fabric, all burned. The damage was great. The incident caused her to decide right then and there to end her aerobics clothing business and to focus on theater and show costumes exclusively.

At Cloud Gate Dance Theatre's practice space in Taipei County's Pali, Lin Ching-ju and the Bangladeshi-British choreographer Akram Khan discuss color swatches for the costumes for Cloud Gate's spring 2007 production of Lost Shadows.

Showbiz? Theater?

Back then she was handling all the clothing for shows at dinner clubs such as Tungwang and Taiyangcheng. At her busiest, she was creating outfits for three new shows a week. As a single mother who was also taking care of two of her own children, she would look after the children and supervise the business closely during the day. She often wouldn't get to sleep until 1 or 2 a.m. Then the shows would let out and friends would call on her for a midnight snack and to discuss business. She was constantly exhausted.

With day and night reversed and so much time devoted to the social aspects of her job, if she suddenly received an order for a serious artistic drama, she herself (never mind her designers and seamstresses) would find it hard to mentally adjust. At that time, her company employed a staff of 20, and she had monthly expenditures of NT$600,000. A theater job would take three months to finish, and she would only receive about NT$200,000. There was just no way to support the business.

But in balancing her time and energy, Lin realized that she had to choose between business and art. For a while she hesitated, but then she recalled the passion she used to have to achieve a high level of art that would lead her even to neglect her health while preparing the outfits for Nirvana. So she gave up the lucrative dinner-show business, and decided instead to work only for theater. It turned out to be a losing proposition. Over several years, she ended up losing NT$7-8 million and was forced to sell one of her house. In 1992 she and her partner went their separate ways. It was at this professional low point that the master set designer nicknamed Squad Leader Wang gave her an old dormitory on an alley off Hsinsheng South Road to use free of charge. She set up her company Kungliao, which is still operating there today.

That same year, at age 44, she obtained a Fulbright scholarship, and went to New York City to study at NYU for a year. During this period she recommended herself to the New York State Theater (home to the New York City opera), and asked to do the dyeing and sewing of 40 monks' habits. With her abundant previous experience, she deftly rendered the prophet-in-the-wilderness look. Moreover, she completed the costumes in seven days. The Americans she was working with were dumbfounded, and expressed their deep admiration.

Later she switched to work for the ballet. At the 50th anniversary of George Balanchine's death, there was a series of performances reviving his dances. It was a rare opportunity that she couldn't pass up. Carefully observing the process of clothing being reproduced for these dances, she learned how to delicately anchor beading and how to place gauzy fabric over sequins on ballerinas' clothes, so that the sequins wouldn't snag on the male dancers' costumes or hair when they lifted the ballerinas. Professional details that she had previously overlooked, knowledge like this was of great benefit to her.

Because Lin's work was so good, when her studies were over the opera house invited her to stay on and work, promising to try to get her the job of designing the costumes for the major opera Turandot. If successful, this was the kind of opportunity that costume designers dream about. But Lin thought about Taiwan, where the artistic soil was poor; she felt that she couldn't abandon the theater friends there, with whom she had suffered and struggled. So she decided to return to Kungliao and to the professional design and manufacture of theater costumes.

One of Lin's sketches of a costume for a theater production.

A simple beauty

Recalling these 25 years of her creative history, Lin recalls, "There was so much that was fresh in the first ten years. It was like I was made of sponge, and was quickly absorbing all kinds of knowledge and skills. Because I was so anxious to perform, there was much that I didn't fully digest but just tossed in." She says this was a stage when she "lacked a personal style."

Her second decade started after she returned from study abroad. Having acquired a broader range of vision, she had more of her own approach and put more energy into research. "Ultimately, dancers' costumes are their second skins. They must be comfortable to wear and stretchable. All these factors can influence the quality of a performance." She began to consider the connections between clothes' structure and the body's rhythms. Gradually, from her confusion--as if emerging from a cocoon--came a design concept that "discarded the fancy for the simple."

In 1998 Cloud Gate Dance Theatre performed Moon Water. It was an important work from the period when Lin Hwai-min had returned to a conception of the oriental body. It took the Buddhist conception that "flowers in the mirror and moon on the water are nothing" as its starting point, incorporating the movements of tai chi into the dance.

To suit the dancers' rhythmic movements--like the passage of the movements of water or clouds--so that the clothes restricted as little as possible, Lin had the men wear no tops and the women tightly fitting skin-colored outfits. Moreover, she did a creative twist with pleated pants; she used extremely thin white chiffon, folded at the waist, so that it looked like a skirt when they stood still but long pants when they were in motion. Like the flow of water or reflections in a mirror, the dancers conjured up an otherworldly beauty.

"From my experience in designing for Moon Water, I began to diligently think about how to integrate modern elements into the traditional commoners' clothes. It extended from the Chinese mother culture to the native Taiwanese theatrical culture." Cloud Gate's productions of Cursive and Cursive II made the most of her stage creativity and pushed her artistry up a level.

Design with thought

Lin observes that many people say Lin Hwai-min is hard to work with because he's always making changes, but she feels that he is "constant from start to finish." She says, "Lin will say something like it's got to be 'Tibetan red" and then you have to move heaven and earth to find it." Furthermore, Lin Hwai-min communicates his wishes very early, at least six months in advance. "And when he gives you a job, he'll give you a book list at the same time. And he knows after two or three sentences whether you've done your homework."

In Cursive, so as to turn the dancers into "calligraphic brushes applying ink," fluidly moving through space, outlining the forms of cursive "grass" calligraphy, Lin boldly chose velvety polyester knitted clothes. "A velvety finish makes clothes more solid and stately. It gives fabric a certain heft that hangs well. It can flow with movement and stretch. The design of the baggy long pants allowed the dancers to be more agile and carefree when raising their legs, turning their body or flying through the air."

In the third decade of her career she has spent more time with the choreographers and directors building conceptions and creating stronger directions. The design is easier for her. In recent years she has been combining the human body with geometric shapes: squares, circles, triangles. She has been "geometric pattern cutting" to give costumes a more modern feel. There is also a minimalism to the lines and colors.

Four years ago for a National Symphony Orchestra performance of the opera Tristan and Isolde, Lin designed a 70-yard-long white skirt, held together with rope that symbolized Isolde's emotional turmoil and the obstacles she faced in love. When Isolde turned her body, the long skirt was pulled toward the sky, like a sail catching the wind; it also marvelously was used as a screen to project images of Tristan and Isolde satisfying their passions in intimate embrace.

Cultivating a new era of theater

When she started in her profession, the general cultural environment in Taiwan was poor, whereas today costume design has for many years been taught at colleges. But Lin still feels hurt: "Taiwan does not lack for design talent, but who wants to sit quietly behind the curtain, stitching away so as to complete someone else's dream? And if the top talent does not have handicraft skills, then exquisite designs are just drawings on paper that can't be realized."

Deeply feeling the importance of strong foundations in basic skills for professional costume designers, Lin, when she came back from the US, carefully picked students to became old-fashioned apprentices, learning correct concepts and methods without having to pay tuition. "Some students when they came to me couldn't even sew a button. But techniques can be learned. Can you put in the hard work? Do you have a passion for work in theater? Those are the key questions."

With regard to the trend toward "one-person theater troupes" in Taiwan over the past ten years, Lin notes regretfully that the government is not providing long-term financial support to excellent performing arts companies. With the general financial uncertainty that these companies face, they are not able to get an early start planning performances. They always have to wait for the money to come in at the last minute before they can recruit personnel and hastily put on a performance.

"You need ample time for the design and manufacture of theater costumes if you want outstanding new ideas. But in recent years, with the time constraints that productions are under, it's often impossible to make the most of your creative abilities." Lin believes that for quite some time shortsighted methods have been practised that are not conducive to the healthy development of a theater company. With no opportunity to see outstanding works, the audiences for theater are gradually shrinking. And once they are lost, they are lost forever.

After midwinter, even Lin's winning the National Award for Arts cannot change the fact that the old dorm that Kungliao has been using as its office is facing the wrecker's ball, and the company must move. But she is behaving as if everything is normal, patiently instructing students how to sew and cut. Concerned above all about the meaning and value of life, she is continuing to expend great effort on behalf of Taiwan's theater world, playing the role of the green leaf that accentuates the beauty of the performers' showy flowers. This woman of great determination not only has a huge infectious passion about the theater; but her artistic accomplishments are also setting the standard for this age.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)