Laozi Lives!

Chang Ching-ju / photos cartoons by Tsai Chih-chung, courtesy China Times Publishing / tr. by David Mayer

January 1999

Could it be true? Was Laozi a plotter of conspiracies? A man without morals? Was he in favor of "keeping the people in ignorance, the better to rule over them"? And did he have a negative, do-nothing attitude?

Laozi was recognized some 2500 years ago as one of China's greatest philosophers, but somewhere along the line his detractors have leveled a lot of serious charges at him.

If Laozi were with us today, however, many would think of much more complimentary descriptions for him: defender of democracy, feminist, environmental activist. . . .

Following the meeting last June between US president Bill Clinton and China's Jiang Zemin, the ROC National Unification Council issued a statement on relations across the Taiwan Strait. Surprisingly, perhaps, this statement quoted not from Confucius, but from Laozi, who has in the past been criticized for having a negative, do-nothing attitude. The quote came from Chapter 61 of Laozi, which states that large nations should show respect to small nations, and vice-versa. At the beginning and end of Chapter 61, Laozi emphasizes that peace among men depends upon the attitude of large nations. If there is to be peace, the latter must give smaller nations breathing space, rather than running roughshod over them.

If Laozi were alive today, perhaps he would be the ideal go-between in peace negotiations between Taiwan and mainland China.

Defender of democracy

Laozi fiercely detested the bullying of the weak by the strong. In the opinion of Professor Chen Ku-ying of the Philosophy Department at National Taiwan University (NTU), Laozi should be considered a champion of democracy. Although Laozi never mentioned anything about elections, Professor Chen argues that he was every bit as democratic as the democracy activists of today. In The Philosophy of Laozi, the scholar Wang Pang-hsiung focuses on Laozi's statement that "the enlightened man has no abiding spiritual focus of his own, but takes his cue from the common man." According to Wang, Laozi spoke this way because there were too many political figures who saw themselves as enlightened, yet unknowingly caused harm to others. In reaction, Laozi called upon people in positions of power to avoid creating chaos in the lives of ordinary people.

Laozi also said that governing a large nation is like steaming a fish for dinner. A ruler who fiddles constantly with policy, trying to fine-tune everything, is just like a cook who keeps turning the fish over when there is no need for it. In the end, the cook just ruins the fish. Wang Pang-hsiung writes, "Of all the competing philosophies at that time, the Daoists were the most democratic in their way of thinking."

Laozi has long been criticized as a tool in the hands of emperors, but some of his writing reads much like a 1990s newspaper editorial. Observing the way people shower rulers with generosity, a latter-day Laozi might have written Chapter 62 as follows: "Rather than give the newly elected president jewelry and cars, they should be teaching him how to govern."

Seeing the corruption of government officials, he might have thundered, "The path of righteousness is smooth and straight. Why do our leaders insist on taking shortcuts? Thanks to corruption at the highest level, farmland lies uncultivated and granaries stand empty. Yet our ruler bedecks himself in sartorial splendor, dines in the finest gourmet style, and skims wealth off whomever he touches. He is nothing but a leader among thieves and cutthroats, a bandit in the presidential palace."

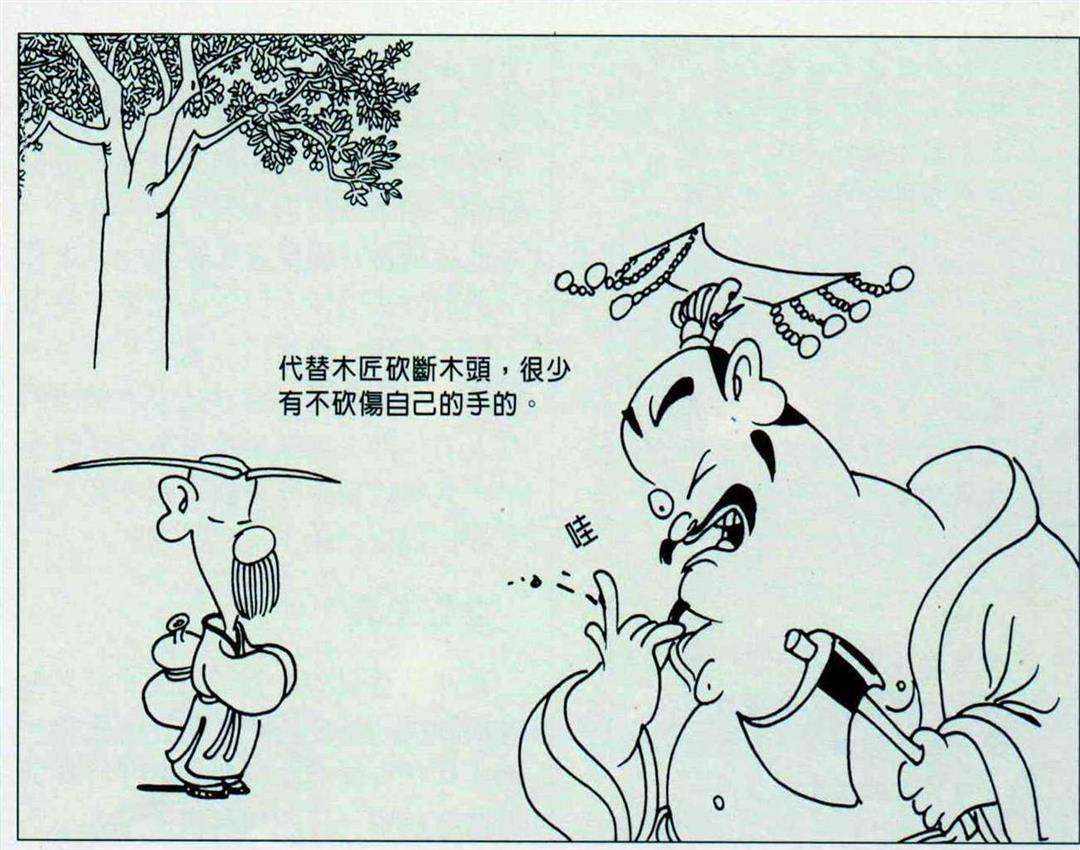

Laozi protested against the despot's draconian enforcement of severe laws which forced people to their deaths, saying: The common people no longer fear even death itself. Would you now use the threat of death to cow them? The ruler who would cut short the lives of his subjects is like an inexperienced clod substituting for the carpenter-sooner or later, he will get his fingers cut.

Laozi as feminist?

According to Chen Ku-ying, Laozi's main intent "was to lessen social conflict, the root cause of which is the wanton exploitation of the common people for the enrichment of a few."

If so, then he would have been critical of "male chauvinism" too, wouldn't he?

Professor Chen, who has studied Daoism for 20 years, often jokes in philosophy classes at NTU that they ought to hang out a portrait of Laozi each time they hold the World Conference on Women. Indeed, the great early 20th-century thinker Yan Fu, who was well versed in the learning of both East and West, wrote in admiration that the central idea of Laozi was "to understand men, and uphold women."

Feminist writers today who speak of "absolute gender equality" no longer represent the leading edge of feminism. Those pushing the envelope today argue that women by nature are superior to combative, quarrelsome males. Laozi, however, beat them to the punch by more than 2000 years.

Laozi discovered long ago that men are no match for women: "If we visited heaven, could we not but find women there?" Do you make use of your five senses as well as women do? "Women, in their passive way, are more than men can handle." One can just imagine Laozi exclaiming: "Men! There you are hatching your plans, and women read you like an open book, so get with it! Learn a lesson or two from them." Laozi also referred figuratively to the inexpressible dao as the mother of all creation.

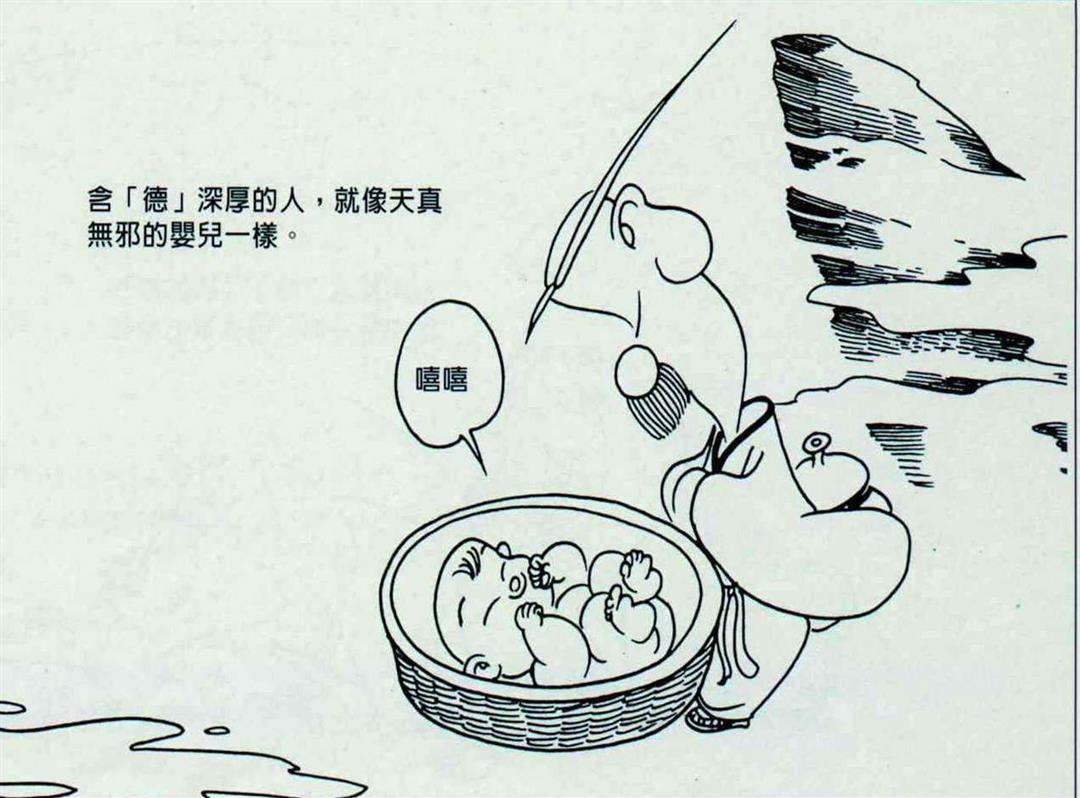

While most of the other key philosophers of his time were busy working out their manly ideas to save the nation, Laozi emphasized letting nature take its course, and was especially interested in children. "Can you maintain your childlike innocence?"

According to Professor Chen, attainment of the "childlike" and the "feminine" represent the highest forms of enlightenment in Laozi's philosophy. "They take two different forms, but share a common orientation."

Laozi as environmental activist

Although no one has ever formally put forward a motion to hang a portrait of Laozi at the World Conference on Women, if he were hoping to wrangle a pass to the annual Earth Day activities, lots of people would invite him to give a talk there.

Both at home and abroad, many have sought in recent years to find a basis in Daoist philosophy for their ideas concerning environmental preservation and the virtues of a simple life. It is reported that Laozi has become very popular in Germany thanks to the Green Party.

The author Meng Tung-li once wrote a publication entitled Laozi's View of Nature on behalf of Yushan National Park. It would seem that Laozi has practically became a leader of the environmental preservation movement.

According to Huang Jui-hsiang, who holds a doctorate in soil science and is an avid reader of China's classical literature, Laozi was especially adept at using water as a metaphor to express his thoughts because he was from southern China, where lakes and rivers abound. Says Huang: "Both Laozi and Zhuangzi were naturalists," and if Laozi were alive today he would undoubtedly be a strong proponent of ecological preservation. He would call for protection of the ozone layer, because he was opposed to excessive consumption and the loss of simplicity. The next great Daoist philosopher to come along after Laozi was Zhuangzi, naturalist extraordinaire. If Zhuangzi were with us today, he would probably be running ecotours.

In reality, both Confucianism and Daoism value simplicity and the maintenance of a oneness with nature. The philosophers of ancient China didn't mention anything that corresponds directly with today's environmental protection movement because the society in which they lived had not yet developed the serious environmental problems that we have today, nor had they depleted so many of the earth's resources or driven so many animals to the brink of extinction. However, their ideal of "looking to heaven for guidance in earthly affairs" was not unconnected with ideas of vital concern today: acting in harmony with nature, living simply, caring about animals, and not generating waste. These are, after all, attitudes and principles that anyone should have. In this sense, to be in touch with one's true nature is to care about environmental preservation.

Avoiding the limelight

Many of Laozi's ideas remain relevant today. If he were here, we would probably hear him talking about "self-discovery," a phrase that's on the lips of young people everywhere in Taiwan.

National Taiwan Normal University's Professor Fu Wu-kuang, who is well versed in Daoist thought, says that Laozi's philosophy is, simply stated, one of liberation.

From political liberation to spiritual liberation, his goal was to undo the fetters, one by one, with which the authorities bind the people. To put it bluntly, "Laozi and Zhuangzi were political dissidents." Professor Chen, who was a dissident himself in his younger days, couldn't agree more.

Laozi was an odd-looking man with great big ears. He agitated 2500 years ago for "liberation" and developed his own system of thought. So, what sort of person was he, exactly?

The great Han-dynasty historian Sima Qian described him as a "hermit sage," and the 20th-century scholar Feng Yu-lan has also stressed the view of Laozi as a hermit in A History of Chinese Philosophy. Although the Chinese have always accorded the same status to hermits as they have to doers of great deeds, Chen Ku-ying argues that Laozi was not a hermit at all, and that the academic community has been mistaken all along on this point. Many people with failed ambitions for fame and fortune disguise their failure by claiming that they, like Laozi and Zhuangzi, have seen through the vanity of this world. Professor Chen, not content to allow Laozi to be misunderstood, argues that as keeper of the imperial documents, Laozi held a position roughly equivalent to that of the head curator of Taiwan's National Museum of History or the director of the National Central Library. Some people compare him to a member of today's Control Yuan, which is charged with the responsibility of ensuring that government officials, including the president, observe the law.

It is written that in his later years Laozi left the capital for good and was traveling through the mountain pass at Hanguguan when he ran across the keeper of the pass, with whom he left the 5000 words upon which his later fame would rest. Thereafter, it is recorded that Laozi lived the life of a hermit, but it must be remembered that he was already an old man by the time of his retirement. He did not leave society behind because of failure. That is why Professor Chen believes it is incorrect to call him a Daoist hermit.

In the Analects, Confucius describes himself as follows: "When excited, I forget to eat; when happy, I forget all sorrow. I can never remember how old I am." And here is Laozi's self-description: "I have three great treasures. The first is compassion. The second is simplicity. The third is the fact that I seek to avoid the limelight." For the most part, the famous philosophers of ancient China all lived simple lives, and this was certainly true of Laozi.

Although Laozi has been classified as a "dissident," he always sought to treat others with compassion and avoided intimidating people with his superior intellect. He spoke of the need for modesty and humility. He also said, "You should not try to stand out from the people around you." While he himself achieved ever higher levels of enlightenment, he did not allow himself to flaunt it, nor was he uncompanionable. And naturally, says Professor Chen, he would not have wanted his readers to become proud of themselves just because they had read Laozi, nor would he want them to feel that they had raised themselves a notch above the madding crowds.

Cut the verbiage!

If Laozi had known that he would be translated into over 80 different languages, and that the New York Times would list him as the greatest author of all time, what would he have to say about the way he has been lionized?

Laozi begins with its famous warning to the reader that words cannot express what the dao really is, and if you try to describe it, you won't do it justice. In the opinion of Lin An-wu, a professor at National Tsinghua University, "Laozi was the first Chinese to realize the limitations of language."

Although Laozi did finally leave us with 5000 words which have since been described as "trenchant" and "superb," he nevertheless emphasizes time and again that knowledge and language always become brittle and end up obstructing our ability to comprehend other humans or the world around us.

Can you imagine what Laozi would say if he knew that he was being touted as a literary giant, and that teachers everywhere were violating his teaching by expounding upon his thought in an endless torrent of words? What, indeed, would he say if he heard that he was being called a feminist, a defender of democracy, and an environmental activist? Perhaps, like the Daoist sage in a recent movie, he would mutter to himself, "What is all this talk about the dao? What a pile of nonsense!"

p.93

If you try to substitute for the carpenter, sooner or later you'll get your fingers cut.

p.95

A deeply moral person has a child-like innocence.

p.96

The soft and feminine often win out through quiescence over the hard and masculine, because they understand how to be humble.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)