Poetry Meets Song— How Lo Sirong Found Her Way Home

Chang Chiung-fang / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by David Mayer

April 2016

Lo Sirong has been showered with praise by her many admirers, who have described her as a “pastoral songstress” and “the best Hakka singer out there.” But such appellations don’t seem to adequately define who she is.

Working via the media of poetry, painting, and music, Lo expresses her longing to return to life, the land, and nature. Even though her album The Flowers Beckon won Lo Golden Melody Awards in 2012 for Best Hakka Singer and Best Hakka Album in the Pop Music category, Lo herself would prefer to slough off her “ Hakka” label and take the broader path of “poet” and “woman.”

So let’s hear how this female artist has used poetry and song to engage in a spirited dialogue with life.

Lo works out of a rooftop addition above her home, and uses the surrounding rooftop space to cultivate flowers and plants. A fern she especially likes is kept indoors, and thrives incredibly well there.

I step into Lo’s creative space and am immediately struck by the strong character of the place. It exudes a sense of the yin principle—the feminine. There is something utterly natural about it, a strong sense of hardy vibrancy, and a note of unending search for balance. “I hope I can get back to a more natural and unassuming way of life, one that doesn’t involve blindly pursuing anything.”

Gomoteu is the name of both a band and a song. A Hakka word meaning something like “wild and unruly, free and easy,” gomoteu is also an apt description of Lo's personality.

Gomoteu and the gang

Lo’s debut album, Everyday, made a huge splash upon its release in 2007.

Her second album, The Flowers Beckon, came out in 2011 to even greater acclaim, sweeping up major honors at the Golden Melody Awards for Pop Music, the Golden Indie Music Awards, the Chinese Music Media Awards, and the Chinese Music Awards. Music critic Chang Tieh-chih is lavish in his praise: “Her music is a scintillating conversation between old Hakka mountain ballads and the American blues tradition.”

Last year, Lo broke out of the “Hakka woman” mold by selecting poems by 12 important Taiwanese women poets—of all different ages and ethnic groups—and putting them to music. The resulting album is titled More Than One.

Featuring lyrics in Mandarin, Minnan, and Hakka, the album garnered Lo recognition as Best Folk Singer at the 2015 Chinese Music Media Awards. According to radio DJ Ma Shih-fang, it is not easy to put a poem to music. “Those bluesy poems that she recorded just practically welled up out of the ground, like a burbling spring. There’s a warmth in them that comes only from the depths of the soul.”

The way Lo switched careers at mid-life shows that she is indeed every bit the “untamed” (gomoteu) person alluded to in the name of her band.

The term gomoteu is a humorous dig in the Hakka language, and means something akin to “untamed and untamable.” It also happens to be the name of a song by Lo. Here is one part of the lyrics: “There are countless monkeys in the mountains, and countless monkeys in your heart, wild and unruly, free and easy....”

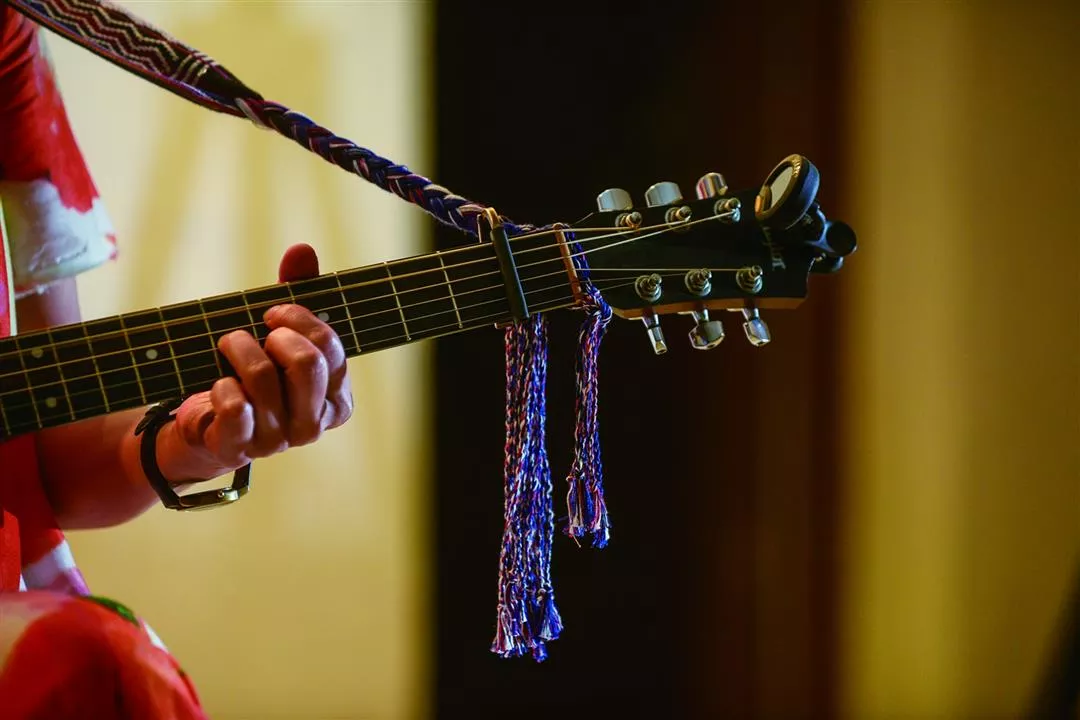

What is more, Gomoteu is also the name of the five-person band she plays with. Lo, who writes the words and music and acts as lead singer, is accompanied by David Chen on stringed instruments, Huang Yu-tsan on acoustic guitar, Io Chen on cello and Irishman Conor Prunty on harmonica.

Although Lo is the band’s main songwriter, it’s hard work turning out songs with broad appeal, so everybody’s participation is needed in the creative process. “Each band member’s opinion matters. Everybody engages in the discussion, and everyone’s ideas are listened to,” says Lo, who adds that the laborious polishing of the music has yielded a strong sense of unspoken understanding among the band members.

o hasn't released all that many albums, but each one attracts a lot of attention.

Liberating the shaman

What was it that prompted Lo to embark on a singing career at nearly 50 years of age?

“Artistic creation makes me feel alive,” says Lo, who remarks that she often feels she has something to say even while feeling, at the same time, that she’s out of step with the world. Acknowledging that she is by turns aloof and gregarious, enthusiastic and indifferent, Lo confides: “For me, all these contradictions are resolved in the process of creation.”

Ma sees a quality of shamanism in Lo’s music. It has the transformative power, he says, to escape the confines of reality and flit off to a different world.

Lo responds: “Poetry is an ancient “shamanistic chant,” if you will. It is at the core of civilization. A shaman channels heaven and earth.” Perhaps it is precisely this transformative power, she says, that sets an artist free and strikes a responsive chord in listeners.

While unwilling to be pigeonholed as a female Hakka artist, Lo frankly acknowledges that this is indeed her starting point.

“Language is the code that underlies culture,” she avers. Language molds a community’s way of thinking, and represents identification with a certain set of values. For Lo, the motivation to create Hakka folk songs originated in a longing for the past—a longing to which she awoke after a long period in which the feeling lay dormant.

The feeling was triggered by a simple dish of scrambled eggs and basil.

Back when Taiwan was much less affluent than it is today, working-class Hakkas would use basil as a sort of medicinal supplement in their food to keep up their strength. “Whenever my mother was feeling a bit run down, she would take some basil and a couple of eggs, add a bit of rice wine, and fix up some scrambled eggs. It really was an excellent comfort food.”

Lo basically forgot about the dish over the years amidst the bustle of marriage and the raising of two daughters, but one day her mother came visiting and cooked up some scrambled eggs with basil for her. “I sat there eating and crying. It made me miss the old days and the old ways so much.”

“Hakka women have it tough,” says Lo. They have to be able to do just about anything. In 2008, Lo conducted a workshop in rural Hsinchu where a group of old Hakka women sat around telling tales of their personal experiences. A 93-year-old woman quipped that she’d done and been everything but a thief: “I was quite literally a beast of burden, the only difference being that I didn’t have a tail.”

Lo left the workshop badly wanting to write a song in tribute to Hakka women. The result was a song about scrambled eggs and basil.

“Throw in a bit of feeling. / Add a pinch of undying love. / The aftertaste that lingers / is the taste of scrambled eggs and basil. / In that simple dish / a mother’s fondest wishes.“

As Lo sings a snatch of the song, I can hear the homesickness unmistakably in her voice, as rich as the taste of basil in the scrambled eggs.

o hasn't released all that many albums, but each one attracts a lot of attention.

The road home

“The road, the wind, yes, led me from home. / The time, the dream, true, took me away. / A daughter gone, sure, may wander the byways. / But, no matter what road the daughter is on, / she’ll still speak with the accent of home.” —Gone From Home.

Her Hakka roots are indeed her starting point, but Lo refuses confinement to things Hakka. “You have to keep moving forward in life, keep moving down the road,” says Lo, whose concern extends to the fate of all women. More Than One, the album she released last year, includes poems in three different languages—Mandarin, Minnan, and Hakka.

Lo selected the poetry for her album in much the way a butterfly gathers nectar. First she read lots of poems aloud to get a feel for the sound and imagery and determine whether they had a “three-dimensional sound.” Then she read lots of other works by the individual authors to understand each poet’s linguistic universe, storytelling style, and world view, and the things each poet cares about most. “I wanted to select works that were truly original and unique.”

“When you sing poetry, the most important thing is to bring the feelings and cultural context behind the words into relief.” A lot of people will tweak the original wording of a poem to accommodate the rhythm or the beat of a song, but Lo insists on keeping the poetry unchanged. She works hard to ensure that a poem and song mesh together as a single work, with a life of its own. She keeps trying out new things until she’s satisfied.

“Climb over those mountains’ peaks / Then you can pass that shrine to the local Land God / Pass several more Land God Shrines / Then that small creek will appear / Plant a few pines and cypress trees / Then you can reach that dense forest.”

When she read Concerning the Value of One’s Homeland, by Ling Yu, Lo felt as though she were slowly perusing a scroll. “Ling Yu explores the way forward one step at a time in search of the place and time of her childhood. There’s no big rush to come up with answers; the idea is to make the readers feel like they are walking along hand in hand with the author. She makes life feel like an inkwash scroll that is slowly unfurled, and then slowly rewound.”

When poets hear Lo’s works, they’re always pleasantly startled, and feel that she’s opened up new possibilities for their poetry, and infused it with new life.

The first time the poet Chen Yu-hong heard Lo sing her work I Told You Before was during a conference session. Chen was rendered speechless, and nearly burst into tears on the spot.

“I told you before, my forehead my hair miss you / Because the clouds comb each other in the sky my neck my earlobes miss you / Because the idle worry of the lane with the suspended bridge and the alley with the grass bridge / Because of the unaccompanied Bach slipping silently into the river outside the city.”

The note of complaint in these lines reveals the core sentiment of the poem.

For Lo, each song carries within it a seed of life that will grow into whatever was meant to be.

“For each song, each potted plant, and each person, there is a certain state they were meant from the start to assume. I hope to get closer to that state, to bring it into being.” She wears a crucifix, but in fact Lo holds to no particular religious belief. What she seeks is balance, harmony, and a return to what nature had in mind all along. “It’s like the Earth, which tilts on its axis yet still travels along its appointed orbit.”

Lo sees no absolute separation between the secular and the sacred. “The act of creating art is at a higher level than humans. When the spirit enters a certain state, you become something of a prophet.”

The band members of Lo Sirong & Gomoteu constitute a miniature United Nations, and their diversity is reflected in the band's rich fusion of different musical traditions.

You can leave home, but you can’t leave your accent behind.

No matter what the venue, Lo Sirong always performs bare-footed. She says that channeling the Earth’s energy as she sings gives her tranquility and strength. (courtesy of Lo Sirong)

-2.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)