David Charles Oakley Shines a Light on Kaohsiung’s Past

Jason Hsu / photos Jason Hsu / tr. by David Mayer

January 2017

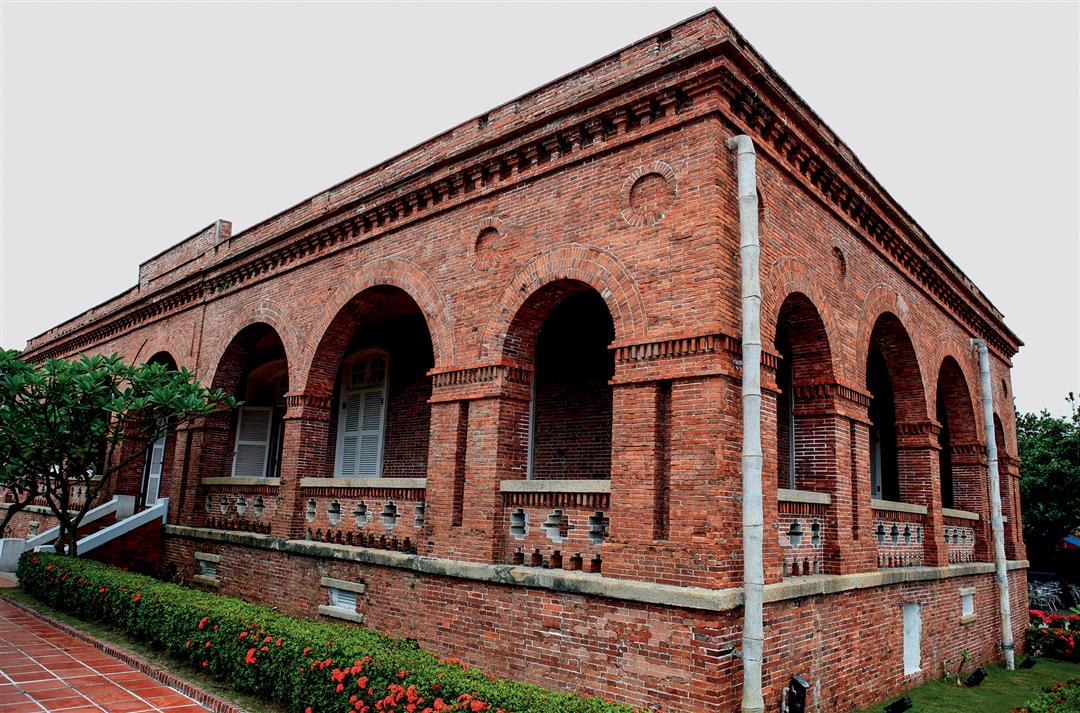

Many a visitor to Kaohsiung over the years will have been attracted to a Western-style red brick building that sits atop Shaochuantou Hill overlooking Kaohsiung First Harbor. The first consular residence in Taiwan to be designed and built by the British Army’s Royal Engineers, it has stood witness to the development of Kaohsiung Harbor, but much of the history that unfolded there more than a century ago disappeared into oblivion as creeping vegetation and shadows encroached upon the site over the years.

In November 2013, the Kaohsiung City Bureau of Cultural Affairs published The Story of the British Consulate at Takow, Formosa by David Charles Oakley, a British man who came to Kaohsiung 27 years ago, became fascinated with the mountain and coastal scenery around Qihou and Shaochuantou, and decided in less than a month to settle there for good. He later discovered the British-colonial-style building on Shaochuantou Hill and became curious about it. Digging into its history, he eventually discovered that it was not the former British consulate, as was generally believed, but actually the consular residence.

Lin Shang-ying, deputy director-general of Kaohsiung’s Bureau of Cultural Affairs, feels that David Charles Oakley’s two books on Kaohsiung provide precious information on the city’s past.

Setting the story straight

When you walk along Shaochuan Street in modern-day Gushan District and head toward Xiziwan Bay, look to the right and you’ll see the former Takao Prefecture Fisheries Experiment Station from the Japanese colonial period. What we now know, however, is that the Fisheries Experiment Station was originally the British consular office. And we know this thanks to the assiduous sleuthing of David Charles Oakley, who wrote a book about the shifting fortunes of the building since it was completed in 1879.

Oakley was a stickler for logical analysis and reasoning. In order to clear up widespread misconceptions about the history and age of the British consular compound at Shaochuantou (including the consular residence and the consular offices, and the location of a cemetery for foreigners), Oakley went to great pains over a period of many years to gather all the information he could find regarding the site. The sources of his copious information included government archives in Britain, the descendants of historical figures, and numerous libraries and private collections in Taiwan and around the world. He then delved into the material with his usual objective rigor and came up with reasonable interpretations of people, incidents, and systems from a century earlier.

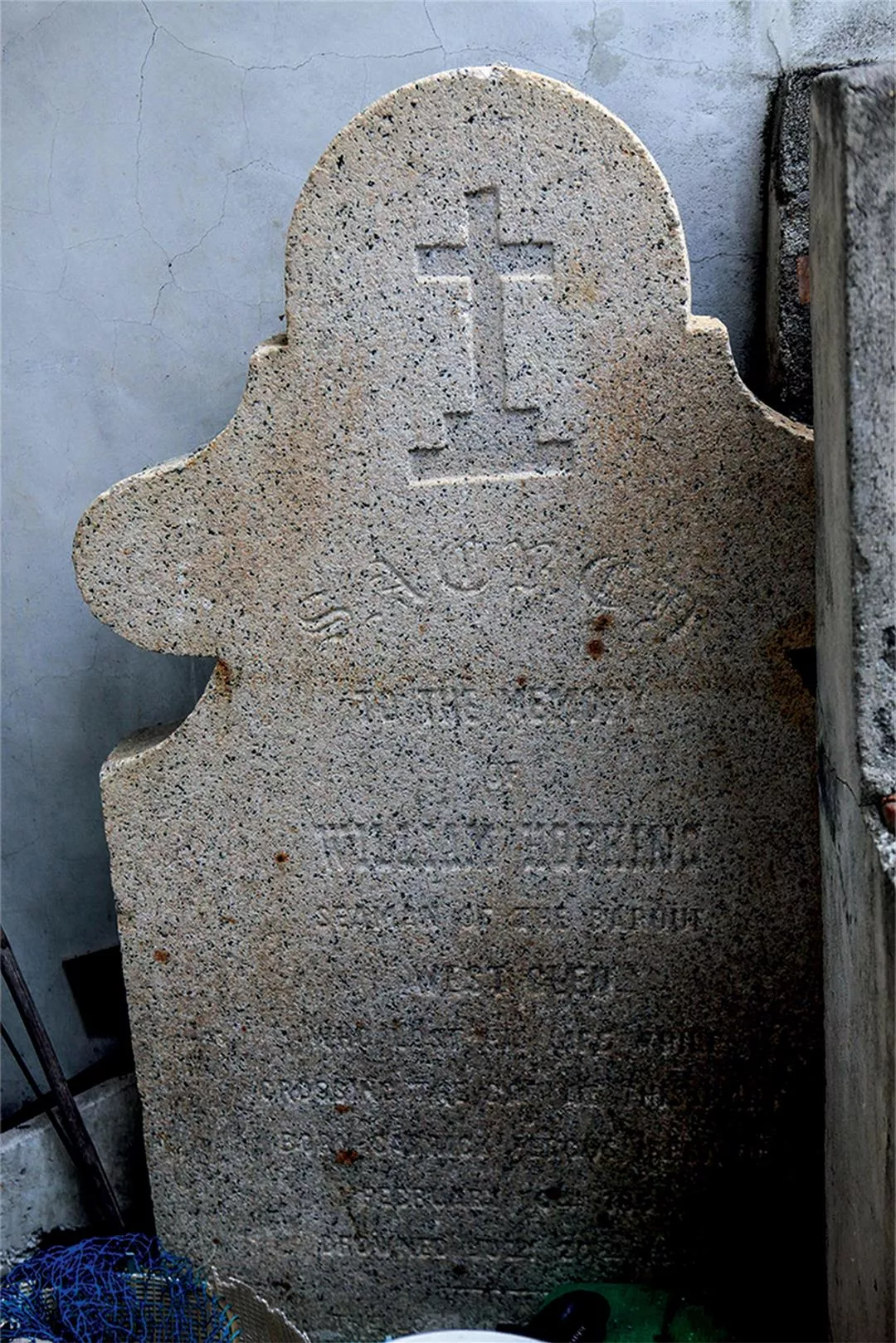

In researching the British consulate, Oakley unexpectedly found a cemetery for foreigners connected with the consulate. He learned that 39 men, women, and children were buried there, and although their remains were probably still there, only three gravestones could be found. After finishing The Story of the British Consulate at Takow, Oakley started writing a second book, The Story of the Takow Foreign Cemetery, to record the stories of the people buried there. Unfortunately, however, Oakley died of an illness in early 2016.

The clean, simple lines of this arched portico at the consular residence exude a 19th-century British charm.

Seeing the book to completion

According to Oakley’s widow, Sarah Kung: “If every person has a mission, then David considered finishing this book his.”

The main point of the book is to ask who those people were, says Kung, who adds that her husband used to do online research constantly. Once, someone in Canada who knew a person buried in the cemetery learned of Oakley’s work and contacted him to provide all sorts of information. Oakley also learned from British government archives that customs employees, the wife of the acting consul, and a Presbyterian minister are among those buried in the cemetery, and not everyone is British; also buried there are people from Germany, Switzerland, and elsewhere, because the cemetery was open to anyone regardless of ethnicity or religion. It is also thought that many of the people there had been ship crew or engineers who worked in Taiwan.

Oakley felt bad that those people had died far from their homelands, and was puzzled as to why their remains were not taken back home. What’s more, the cemetery was not well maintained, and had very nearly disappeared entirely. He felt that the people buried at Takow Foreign Cemetery should not be forgotten; on the contrary, they should be memorialized, because they had made important contributions to Taiwan in different fields.

Kung recalls that her husband would often ride his bicycle to interview people throughout the local area. With his classic British scholar’s personality—brimming with curiosity, concerned about logical analysis and reasoning—Oakley took an avid interest in the history and culture of Taiwan. His book is the crystallization of 20-plus years of field surveys, academic research, and correspondence with family members of the deceased.

After Oakley passed away, Kung in her mourning decided to organize her husband’s research materials and get them stored properly away. But as she read through the unfinished book, she discovered a fascination of her own with the matters set out therein. “So I decided to finish the book for him.”

David Charles Oakley’s widow, Sarah Kung, completed his second book and got it published, thus ensuring that his valuable work would see the light of day.

Telling the history of Takow

According to Lin Shang-ying, deputy director-general of the Kaohsiung Bureau of Cultural Affairs, Oakley provides an extremely detailed account of how the Takow Foreign Cemetery has changed over the past century, and incorporates his research results as well as information provided by the friends and relatives of the deceased to recreate their lives in vivid detail. To get at the facts, he had to ignore taboos and mistaken ideas that local residents held regarding the cemetery. All who’ve read this posthumous work have found it very moving.

Lin notes that when the Bureau of Cultural Affairs learned in 2003 that there was a foreign cemetery at the British consulate and that three headstones were still standing, it considered how to handle the matter, but a decision couldn’t be made quickly because the history of the cemetery was so unfamiliar, the information was so difficult to find, and there were so many factors involved, such as the different nationalities of the deceased, the difficulty of contacting their family members, whether bones remained beneath the headstones, whether family members would agree to let graves be moved, where they should be moved to, and so on.

“We refurbished the British consulate and put records and historical artifacts on display there,” says Lin. It was not possible to resolve the matter of the cemetery in a short period of time, but the Bureau of Cultural Affairs spent a lot of time and effort to publish Oakley’s two books, partly to record Kaohsiung’s past, and partly to thank the foreigners buried in the cemetery for all they did for Taiwan.

Customs employees, the wife of the acting consul, and a Presbyterian minister are known to be buried in the cemetery at the British consular compound. This may also be the final resting place of seafarers as well as engineers from various countries who worked in Taiwan, but the headstones are too deteriorated to know for sure.

Academic rigor

Professor Lee Chien-lang of the Graduate School of Art Management & Culture Policy at National Taiwan University of Arts wrote in his preface for The Story of the British Consulate at Takow: “In addition to its painstaking historical research, another important part of the book is the personal correspondence between the author and people connected in some way or other with the consulate. This book clears up numerous historical facts, and provides many valuable images and photographs of people. For any student of relations between Taiwan and Britain a century ago, this is a very important work.” Ang Kaim, an associate research fellow at the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Taiwan History, also has glowing praise for Oakley’s academic rigor: “The author tells his readers about the diplomatic and business-world struggles and skullduggery that unfolded at the consulate in a time gone by, and provides fascinating historical vignettes from the community of foreigners in Takow. It’s a great read.”

Chang Shou-chen, a former professor at the Wenzao Ursuline University of Languages who helped translate The Story of the Takow Foreign Cemetery into Chinese, admires Oakley’s passion for life and the way he plunged into research on local history after settling in Kaohsiung, especially his focus on the foreign communities that sprang up in Tainan and Takow (Kaohsiung) after the Qing-Dynasty rulers in Beijing were forced to open several ports, including some in Taiwan, to foreign interests after the signing of the Treaty of Tientsin in 1858.

Chang says that The Story of the Takow Foreign Cemetery is packed with interesting content. Particularly noteworthy is Oakley’s recounting of the life stories of foreigners who died in southern Taiwan and came to be buried at the Takow Foreign Cemetery.

Oakley left behind a rich body of historical materials and anecdotes pertaining to foreigners in Taiwan. His position as a native speaker of English was an advantage, and the quality of his work was further boosted by his rigorous approach to historical research, his strong affection for Kaohsiung, and his zest for field work.

Customs employees, the wife of the acting consul, and a Presbyterian minister are known to be buried in the cemetery at the British consular compound. This may also be the final resting place of seafarers as well as engineers from various countries who worked in Taiwan, but the headstones are too deteriorated to know for sure.

This watercolor image of the British Consulate at Takow, though made recently, nevertheless achieves a retro look that evokes the history of the place. (courtesy of Kaohsiung Bureau of Cultural Affairs)

Lifelike waxworks and artifacts at the former British consular compound take visitors back to the Shaochuantou of 1879.

The British Consulate at Takow lies half-hidden near a hiking trail amid thick vegetation, and offers a commanding view of the Asian New Bay.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)