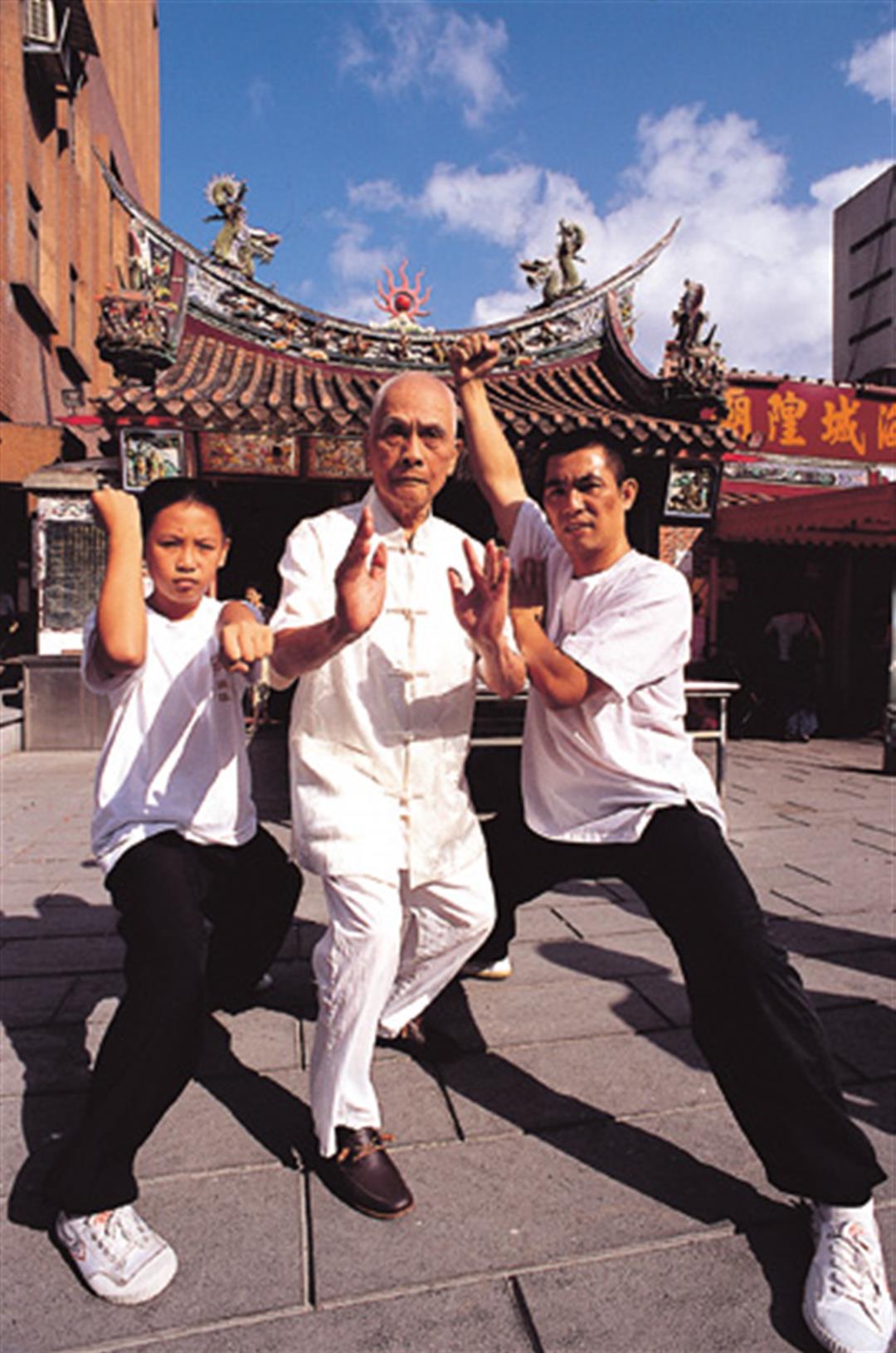

At the grand opening ceremony for the Asian Games in Doha in December 2006, spectators watched in delight as each country showed off unique folk art performances from back home. Chinese people were represented by the lion dance, a traditional harbinger of good fortune that plays an indispensable role at temples and shrines throughout Taiwan when it comes time for the gods to hop in their divine palanquins and take a spin around the surrounding countryside or cityscape, or put on a raucous parade for the birthday of the Buddha or some other deity. Taiwan's lion dancers are experts in both dance and martial arts, and never fail to thrill onlookers with their artistry and athleticism.

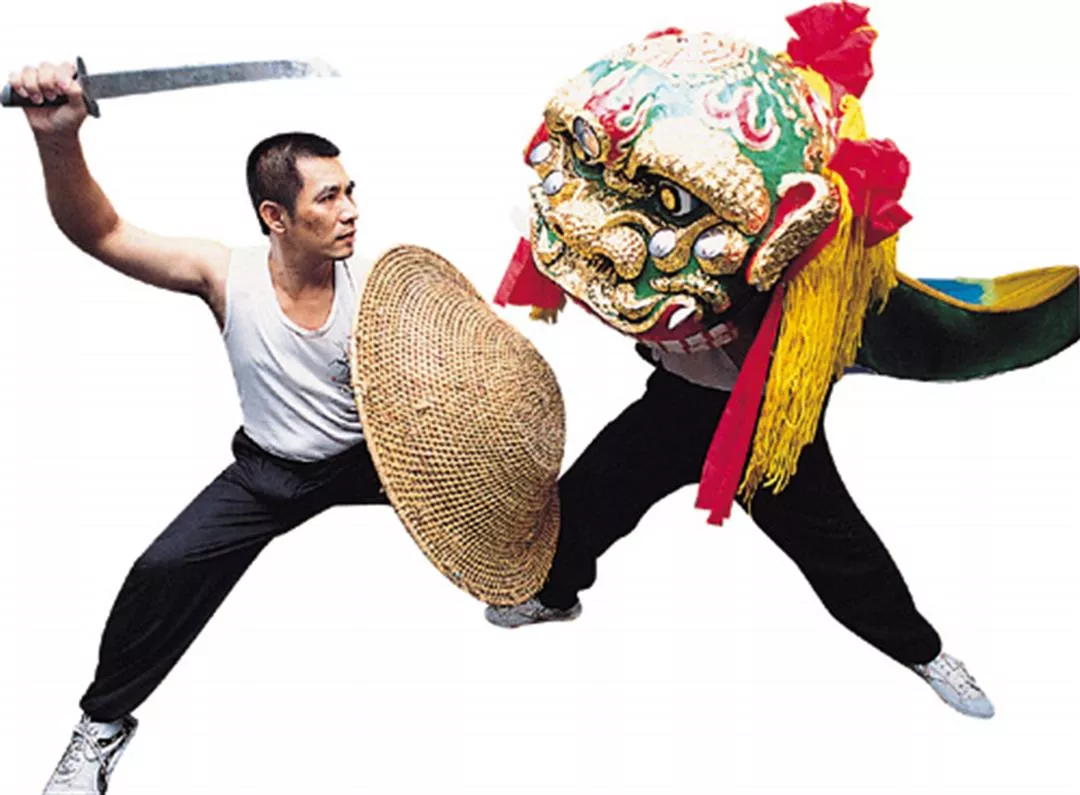

The atmosphere surrounding the brilliantly ornate lion is solemn yet playful; the beast's very soul shows through in each movement as the vaulting, crouching, tumbling animal licks a paw, rubs its whiskers, and pretends to take an occasional "catnap."

Not just anyone can produce these intricately handmade Taiwanese lion heads, for their making requires a wide range of skills. The basic steps include modeling a clay mold, forming a cloth blank over the mold, and then painting and dyeing the blank. But this hybrid art form, combining religion and artisanry, is lapsing into oblivion in the face of modern mechanized production. Fortunately, however, it is still being preserved and passed on by Hung Lai-wang, or "Lion Head Wang," as he is respectfully monikered in Taiwan's folk arts community.

Born in Peitou in 1915, Hung Lai-wang at age 91 remains spry and energetic, and still practices a mean "three-kick tiger fist." The old master continues to make lion heads today, and has turned out over 1,000 of them over the past eight decades.

The Manka district (now called Wanhua) was once the commercial heart of northern Taiwan. When temples "invited" gods over from China, the statues generally passed through Manka on the way to their destination. Craft specialties and performance troupes naturally grew up to serve the needs of the religious community. One of the most famous artisans was "Water Master," who made lion heads at his home near the foot of Taipei Bridge. In 1924, a lion dance troupe in Peitou hired Water Master to teach his craft up in the northern neck of Taipei. There he passed on the secrets of his success to a "Master Yi Tu."

The nine-year-old Hung Lai-wang loved to hang around Master Yi Tu, doing odd jobs and learning to make lion heads. Despite his family's exhortations to concentrate on his studies, young Hung was much more enamored of the workshop.

On graduating from elementary school, Hung took up an apprenticeship with the family's Japanese tenant, a dental technician. He learned to make dental molds, which eventually became his occupation.

"Transportation was not well developed back then. I had to travel between Peitou and various points along the northern coast--Tanshui, Chinshan, Chiufen, Chinkuashih. I'd stay at each stop for a period of time, pulling teeth, making dental molds, and putting in false teeth, but as soon as I had any free time I'd go take part in local temple fairs, or seek out local martial artists and practice with them."

After finishing a road trip and returning to Peitou, Hung would always rush to find his lion dance buddies. They would work together to find ways to take his newly learned martial arts moves and incorporate them into the lion dance.

Hung stresses: "Most lion dance skills have to do with how you use your hands, move your feet, use your body, your legs, and the like. A lion dancer without a strong grounding in martial arts cannot make a lion come to life. He can't project an imposing air, or show the lion's agility."

Lion dancers in Peitou back then all had martial arts training. Their lion dance skills were formidable, and the troupes were very much in demand for temple fairs around northern Taiwan. There were many lion dance troupes in Peitou, the more famous among them being the Ching Chiang Lion Troupe, the Hsin Wu Lion Troupe, and Hung's own Central Lion Dance Troupe, established in 1955. In their heyday, there were over 20 troupes in Peitou, which came to be known as "the lion's den."

Lion heads wanted

In any lion dance, all eyes are drawn to the lion's head. The steps in the production of a handmade lion's head are numerous and complex, and the materials must be processed with loving care.

First, the clay for the lion head mold has to be taken from "Peitou soil" at Kueitzu Hollow in the Tatun Mountains. The soil comes with grit and lumps, and so must be washed, which in the old days was usually done in settling pools. The soil was dumped into the pools, which were then filled with water. The soil and water would then be stirred and left to settle overnight. The clear liquid was drained off the next day, while the fine-grained clay was transferred to another settling pool. Numerous repetitions yielded a high-quality clay.

With high-quality clay in hand, the next step is to age it, allowing bacteria in the clay to secrete acidic substances and colloids. During the aging process, water in the clay becomes evenly distributed, improving viscosity and plasticity.

Aged clay is usually cut into blocks for storage, then prior to use is soaked in water. After the clay is fully softened, the extra water is drained off and the clay is stomped on to knead it to an even texture. Before modeling begins, the clay is wedged to prevent deformation or cracking after the body has been formed. Hung points out that good clay is extremely smooth, and feels oily to the touch, which is why it's called "clay oil" in Chinese.

After the mold is completed, it is covered with a blank of cheesecloth or kraft paper. When the thrifty people of earlier years used kraft paper, it came from used cement bags, though they normally made their blanks from fabric--cheesecloth torn into squares of five and ten centimeters.

"The bottom and peripheral parts of the lion head are covered with the larger pieces of fabric, but you have to use smaller pieces to get sharp relief for the facial features," explains Hung. "Before using the cheesecloth you have to soak it in water so that the blank won't shrink after coming in contact with the water-based adhesive. Only after it's been soaked and dried can you tear it into small pieces."

Hung Wen-ting (left) is a vigorous promoter of Taiwanese lion dancing. Over a decade ago he began teaching lion dancing and martial arts at elementary schools, civic groups, and lion dance troupes. He is shown here teaching a class at Wego Elementary School in Peitou.

Complexity of the "blank"

The adhesive was prepared in the old days by adding four or five ounces of lime to a small basin of pig's blood and beating with a whisk made of dried rice stalks. Hung used raw lacquer in the past to make the paint penetrate more readily into the blank, but raw lacquer is poisonous. Skin contact, and sometimes just the smell of it, will cause a reaction. In mild cases, the skin on the arms swells and becomes extremely itchy. More severe reactions can cause swelling and lacquer sores over the entire body, and the unfortunate soul who breaks the skin by scratching can bloat up almost beyond recognition!

Hung vividly recalls the terrible itching he suffered in his own bout with lacquer poisoning over 70 years ago. Today lacquer has been replaced with paste and resin, so his son Hung Wen-ting, who started learning to make lion heads 11 years ago, hasn't had to deal with that particular problem.

To make the cloth blank, the cheesecloth squares are first soaked in water, brushed with adhesive, and adhered to the head, one piece at a time. Once an entire layer of fabric has been applied, the head is left to dry in the dark. After it has dried thoroughly, it gets a second layer of fabric.

"In sunny weather you can get on one layer of fabric in a day, but in cloudy weather it sometimes takes two days, and if you're working to meet a deadline you have to use fans to speed the process." Hung explains that the drying must be done in the dark. If you get anxious and expose the head to sunlight, the fabric will dry on the surface but still be damp underneath; then if you rush to put on the second layer, the fabric will deform later on.

In recent years some lion head makers have outsourced the work to suppliers in China to keep up with demand and save money on labor, but the artisans there lack experience. They don't presoak the cheesecloth, and they set the heads out to dry in the sunlight to speed things. After these heads go into service, the fabric eventually becomes terribly deformed, calling to mind the old Chinese saying about "drawing a tiger that looks more like a dog."

Most lion heads in the old days were made of five layers of fabric, but change came in the 1980s with rapid economic growth and the rezoning of agricultural land in connection with urban planning. New affluence brought the building of new temples. The gods had to be entertained, and demand for lion dances picked up. Wear and tear increased, prompting makers to use as many as ten layers of fabric. After a cloth blank is finished, the next step is to remove it from the mold (by smashing the mold with a machete) and paint the fabric.

Over the past eight decades Hung Lai-wang, nicknamed "Lion Head Wang," has turned out over 1,000 lion heads, and they've become highly sought collector's items.

Paint and gold leaf

After the cloth blank is removed from the mold, the lion's mouth is formed from two bamboo sieves, one for the upper jaw and one for the lower. These enable the lion's mouth to open and close during performances. Directly behind the mouth is an oxbow-type wooden frame. The dancer grips the frame in both hands to manipulate the lion's head and mouth during performances and execute crowd-pleasing leonine movements, such as licking of paws, biting, offering up food, and all manner of frisky scampering.

Next comes painting of the cloth lion head. "Golden-face" lions are the most common type in Taiwan. To achieve the golden face, gold powder is mixed with natural lacquer and applied to the fabric. But first raised lines are applied to the lion's face, much as a baker decorates a cake, using a decorative caulking material made from the spackle that painters use to fill cracks in walls. This is mixed with hardener and pigments, loaded into a caulking gun and squeezed onto the fabric following the lines of a penciled pre-sketch, thus achieving a raised effect. Only a highly skilled artisan can apply the soft caulking material with the necessary control.

After the decorative material dries, a coat of yellow primer is sprayed on. Yellow is used because it is close to the color of the gold leaf to be applied next. Before the gold leaf is applied, a coat of size is laid down. Drying time for the size must be carefully controlled, as the quality of the gold leaf depends on it. Apply the leaf too soon and it won't go on evenly; apply it too late and it won't adhere.

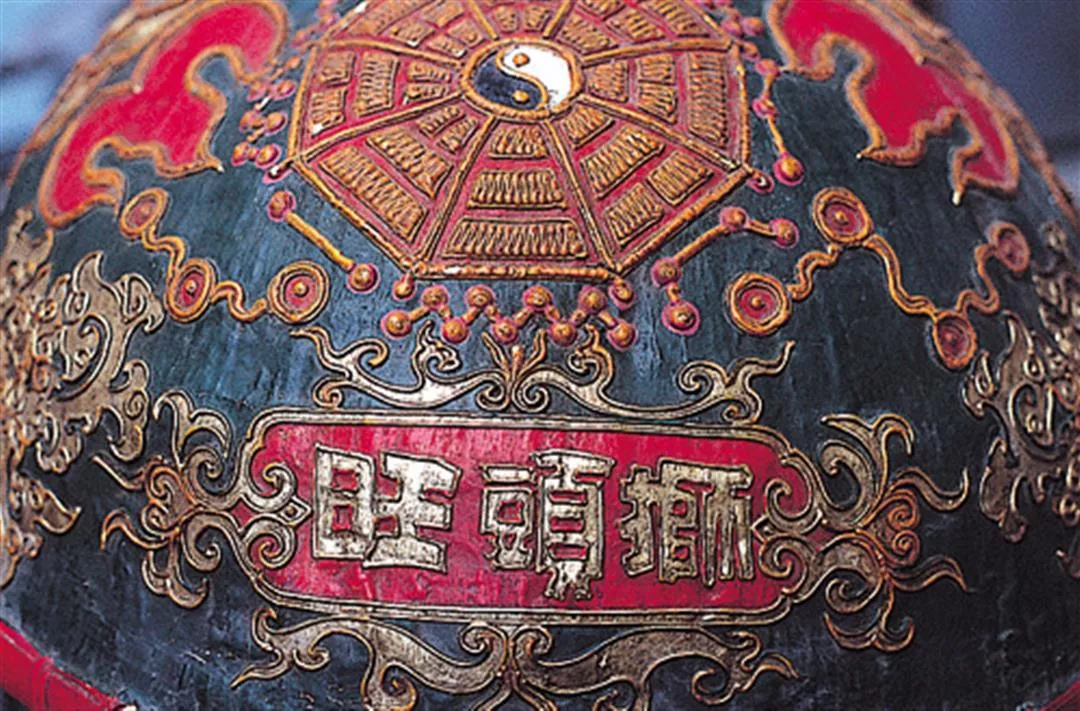

After the gold leaf is down, symbolic designs on the lion head are filled in with a variety of colors. Stylized flames on the forehead are painted red. Behind the flames there is usually an octagonal bagua trigram grid and a black-and-white Yin-Yang symbol. All lion heads feature Big Dipper diagrams on either side of the forehead, sometimes painted on, and in other cases represented by seven coils of hair.

Each symbol has its meaning. The flames represent the lion's imposing power and unbridled yang essence. They show that the lion is a banisher of malevolence. The bagua grid, Yin-Yang symbol, and Big Dipper all advertise the lion's ability to ward off evil and protect the home. A mirror mounted over the flames represents the five-colored mirror that shows the "true colors," good or evil, of whoever looks into it.

When a lion pays a call at a temple, someone of respected stature will burn paper money as an offering, symbolically asking those in charge of the temple to come out and receive their guests. Hung Lai-wang is shown here leading his lion troupe in a performance at Hsiahai City God Temple in Taipei.

Birth of the lionheart

After the painting is completed, the "accessories" are attached. Jute fibers dyed gold, silt green, red, and black, for example, make up the lion's mane. Then the head is sewn to a body made of colored cloth. For an eye-catching flourish, palm leaves are tied in a bunch to serve as the lion's tail. After two or three months, a handmade Taiwanese lion is finished!

After the lion is completed, it's still not ready to go into service. There must first be an "eye opening" ceremony, prior to which the lion's eyes are kept covered with a red cloth. On an auspicious date, sacrificial offerings are prepared and a highly respected Daoist priest is invited to paint in the pupils of the lion's eyes with a red brush. This action is called "introducing the light," and once completed the lion acquires its god-animal spirit.

According to Hung, the most exacting standards call for the eye opening ceremony to be held beside a mountain stream. The mountaintop symbolizes the lion's position as king of the beasts, while the stream signifies that the lion dance troupe will continue to flourish for unlimited generations to come.

Chen Te-an, head of the Tie Yueh Chin Lion Troupe, owns a collection of Hung's handmade lion heads. He is full of praise for the old master's skill: "Many lion heads out there look positively snarling, but Master Wang's have gentle lines. The lion's expression is friendly and alive. The point of an 'auspicious lion' is to make people feel happy. The lion dance is all about bringing good fortune to templegoers."

After the cloth blank is removed from the mold (top), gold powder is mixed with natural lacquer to make a varnish that is applied to the fabric. Putty-based decorative caulking is then applied with a caulking gun. The result is a "golden-faced lion" (bottom).

Fang of the lion

The most eye-catching feature of the lion head during a performance is its metal teeth, which glint in the light when skies are sunny. Hung explains that in earlier times the teeth consisted of two short sabers, with the hilts mounted in the bamboo mouth and the blades protruding outward like fangs. The person manning the back of the lion also wore a pair of stiletto-like weapons at his side.

The carrying of short weapons amid the hustle and bustle of a lion dance stems from historical circumstance. When lion dance troupes first came over to Taiwan from China in the 18th century, brigands roamed the island and ethnic tensions often sparked armed melees and riots. For self-defense, villages typically established martial arts halls where local youths learned combat skills. But there was little spare time in an agricultural society, so the martial arts halls would hire lion dance troupes with expertise in both martial arts and lion dancing. When the locals had free time, they would train with these troupes. It was a fun and healthy outlet, and also provided a source of cohesion in the community; thus lion troupes were ubiquitous in Taiwanese farming villages.

The bad years

When time for a temple fair rolled around, natural rivalries between villages created tension. Martial arts halls from different fighting schools were intensely competitive, and apt to talk trash to each other. Words often led to brawls. On such occasions, the short sabers in the lion's mouth, and the stilettos carried by the lion dancer in the rear, came in extremely handy.

With an air of regret, Hung relates that during Japanese rule anyone caught instigating a melee at a temple fair would be put in custody, which for repeat offenders meant incarceration for 29 days. After the Nationalists took over Taiwan after WWII and declared martial law, lion troupes invited to perform outside the Presidential Palace were not allowed to carry weapons, and any found would be confiscated. Performances by lion dance troupes without weapons were much less interesting.

The Kaohsiung Incident of 1979 threw a political chill over Taiwan. Alarmed Nationalist authorities took every opportunity to crack down on meetings and organized groups of almost any description. They moved with special diligence against homegrown lion dance troupes, as these were very "Taiwanese" and combative by nature. Only too aware of the many people slaughtered in the February 28 Incident, and of other White Terror deaths, lion dance troupes disbanded or changed their names in droves to keep out of trouble. Some even burned their valuable handmade lion heads. The art of the lion dance was under siege.

It was not until the late 1980s, after the Chiang family's reign came to an end and homegrown Taiwanese culture acquired cachet, that people throughout Taiwan again dared invest in revamping the temple-based martial arts halls. Only then did Taiwanese lion dance troupes start to see hopes of a revival. Unfortunately, some underworld gangs have gotten involved in lion dancing and run its reputation into the ground, using temple fair performances as cover for violence. Schools strictly forbid students from involvement in lion dancing, which makes it hard to train a new generation of practitioners.

Hung Wen-ting stresses, however, that lion dancers and other traditional performing troupes are very much a part of popular culture, and the bad reputation they now have is due to the failure of some troupe leaders to instill proper values and attitudes among troupe members.

Explains Hung Wen-ting: "For example, when a lion dance troupe on parade passes by a temple, it's supposed to stop, do a simple performance, and pay its respects, and those in charge generally give a respectful greeting in return." This mutual respect is a standard part of the culture of traditional performance troupes, and no different in kind from the respect people show when socializing at the individual level.

He confidently adds: "In recent years the Taichung County Matsu International Festival has attracted a lot of favorable attention. If the government and private sector can work together to promote the spirit of traditional performing arts, we can difinitely attract tourism."

The Taiwanese-style lion head is thick and heavy. It can only be properly handled by someone with strong martial arts skills, and is categorized as a "martial lion."

Kid with the right stuff

Hung Lai-wang didn't go out of his way to encourage his children to get involved in the life of temple fairs, but Hung Wen-ting, born in 1962, from an early age showed a keen interest in the percussion routines. He listened to his father beat on the drums early every morning at the nearby Yellow Emperor Shrine. It soon became clear that he knew the rhythms by heart, for he began tapping them out himself at all hours of the day on the wooden staircase at home.

The father quietly observed it all, and allowed Wen-ting at age seven to don the suit of a "heavenly general" and proudly beat the drum on a parade float at a temple fair. He would never forget the experience.

After graduating from junior high school, Hung Wen-ting start working as a cook under his uncle, but never lost interest in lion dancing and martial arts. At a temple fair he met Chang Ke-chih, a master of the Southern Shaolin style, who accepted him as a disciple. Employed at the time as a restaurant chef, Wen-ting volunteered for the late shift. Getting off work at midnight, he would hop a bus at Peitou and travel all the way to Chungching North Road to practice martial arts. At the same time he was also learning karate from Kao Chien-lung, and the Taizu Fist boxing style from his father. After finishing his mandatory military service, he began studying Cantonese-style lion dancing and "the 18 martial arts weapons" from Li Jih-sheng, a noted master of Choy Lay Fut kung fu (a Cantonese boxing style).

Being 47 years apart in age, father and son not surprisingly think differently on many issues, despite their shared love of martial arts and lion dancing. The elder Hung heads the Central Lion Dance Troupe, and would have liked his son to succeed him, but Wen-ting opted instead in 1987 to join with a friend of his own generation in founding Fu An Lion Dance Troupe. In 1996 he took charge of the Fu An Lion Hall and started learning from his father how to make lion heads.

"Dad's not the type to sit back and relax. Whenever I'm working on a lion head he will come over and makes improvements." Wen-ting's older sister Ming-chu also notes: "Once Dad sits down and starts modeling a lion head, he won't even take time out to eat until he's turned out something to his satisfaction." This persistence and concentration is what earned Hung Lai-wang a lifetime achievement award from the Taiwan Provincial Government in 1998, as well as a Cultural Heritage Award in the Folk Art category in 2006.

Handmade Taiwanese lion heads, heavy and imposing, are the result of an extremely elaborate production process.

Passing the torch

Wen-ting wants to see his father's art passed on to coming generations, but he's all too aware that simply relying on the old folks to hand down their knowledge, as his father has done to him, is not enough. Educational support is needed too. He began teaching courses a decade ago at elementary schools, civic groups, and lion troupes, and the Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission also sponsors him as a cultural ambassador to Thailand and Malaysia, where he teaches in numerous overseas Chinese communities.

"When I first taught elementary students, I got well-intentioned reminders that students today are pampered, so I shouldn't push them too hard. But in fact, if you just take advantage of the kids' natural playfulness and curiosity, you can get them interested." Under Hung Wen-ting's direction, the students at Taipei's Dong-Hu Elementary School took part in a national folk sports contest in 2004 and won an award for excellence in the lion dance category. Then in 2005, Wego Elementary School in Peitou won a first-class award for lion dance troupes at the same contest.

Hung Wen-ting's own martial arts credentials are impeccable. At the International Kung Fu Masters Performance and Championship in Hong Kong in 2004, he faced down the top masters from all over China to take a pair of gold medals in boxing and weapons.

Hung Wen-ting describes the lion dance as both a calling and an occupational specialty, whereby one studies not only fighting and dancing, but also how to respect heaven and one's fellow man. A child who develops an interest can enroll in a sports academy or apply for athletic admittance to a regular school, and treat it as a specialist skill to be improved.

In a bid to promote lion dancing and place it before an international audience, the Hungs in September 2006 established a lion dance association dedicated to teaching about the art, starting with the basics of painting a lion head. The idea is to give course participants a chance to use their imagination in the process of painting the heads, then gradually move from there to instruction in how to model the clay molds, with the hope that students might take an interest in learning how to do the lion dance, which in the end would lead to promotion of martial arts.

Clay is used to make the mold for the lion head.

Going global

A third-generation Hung is already showing great promise at age ten, having learned the Hongmen fan, zhixian boxing, the Shaolin staff, and the Taiwanese lion drum. Asked why he likes lion dancing and martial arts, Hung Yu-chieh answers in a shy, childish voice: "I just like it!"

His guileless response calls to mind Hung Lai-wang as a boy over 80 years ago, hanging around Master Yi Tu and playing with clay. The sheer fun of it led to the acquisition of formidable technical skills. Over 20 years ago, it was the sheer fun of it that prompted Hung Wen-ting to practice martial arts at all hours of the night. Now, when a member of the third generation comes out with the simple: "I just like it," one can't help feeling hopeful about the future of Taiwanese lion dancing.

For the fun of it, they work on their craft and pass it on. For the fun of it, Taiwanese lion dancing stands a chance of taking its place on a global stage.

All you need is passion.

Lion dancing is somewhat similar to jiao di xi (the "leg contest game"), which was among "the 100 games" of the Han dynasty. It is also mentioned in the New Tang History, written during the Song dynasty by the great Confucian scholar Ouyang Xiu, who wrote: "There are two cymbal players, four dancers, and colorfully decorated lions. Each lion has 12 persons dressed in a distinctive manner."

Scholars have determined that immigrants from southern Fujian brought the lion dance to Taiwan in the 18th century. The earliest style to hit the Taiwan shores was the southern Fujian lion dance (divided into two different schools), followed later by Hakka, Cantonese, and Peking styles.

Southern Fujian lion dancing continued to evolve in Taiwan, splitting into southern and northern styles. The southern style features a mouthless "closed-mouth" lion, while the northern lion has an open mouth. The term "Taiwanese lion dancing" covers both these styles. The Taiwanese lion features a heavy head; solid martial arts skills are needed to handle it properly, thus the Taiwanese lion is a "martial lion." This is different from the Cantonese-style lion that features prominently in the Hong Kong movie Once Upon a Time in China. This latter is more ornate and playful, and the performers can bound with it across the tops of high posts.

Since the 1970s, improved transportation infrastructure has enabled lion dance trainers in Taiwan to traverse the entire island, and the distinction between the northern and southern styles has broken down. The Taiwanese lion dance has been enriched in the process.

In addition to regional differences, Taiwanese lions also differ from one school to the next. Besides the closed-mouth and open-mouth distinction, there is also the matter of which agricultural implement is used in framing the head, thus the existence of fruit-basket lions, chicken-cage lions, wicker-scoop lions, box lions, etc. Some lions have a five-color face (red, black, white, indigo blue, and yellow), and are called "five-element" lions, while "golden-face" lions have a face painted primarily in gold. Golden-face lions are the most common type today, partly because they are used by many different schools, and also because gold is a symbol of wealth, status, and good fortune.

(Kuo Li-chuan/tr. by David Mayer)

The extremely ornate Cantonese-style lion head features a sharp sense of depth, and looks quite playful.

Hung Lai-wang (a.k.a. "Lion Head Wang") is determined not to let Taiwanese lion dancing fade into oblivion. He is a highly respected figure in both the religious and artistic communities.

The cloth blank is made by sticking pieces of cheesecloth to the clay mold.

Hung Lai-wang's youngest son, Hung Wen-ting (left) has carried on in his father's footsteps, establishing Fu An Lion Dance Troupe. A formidable martial artist, Wen-ting has taken gold medals in boxing and weapons at the International Kung Fu Masters Performance and Championship in Hong Kong.

The clay for the lion head model is refined from "Peitou soil," which is taken only from Kueitzu Hollow in the Tatun Mountains. The texture of the clay is very smooth, and feels oily to the touch, which is why it's colloquially referred to as "oil clay."

The stylized flames on the lion's forehead are filled in with red coloring, and represent the lion's imposing power and unbridled yang essence.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)