Taiwan's Master of Distemper Painting: Lin Chih-chu

Kuo Li-chuan / photos courtesy of Hsiung Shih Art Monthly / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

September 2006

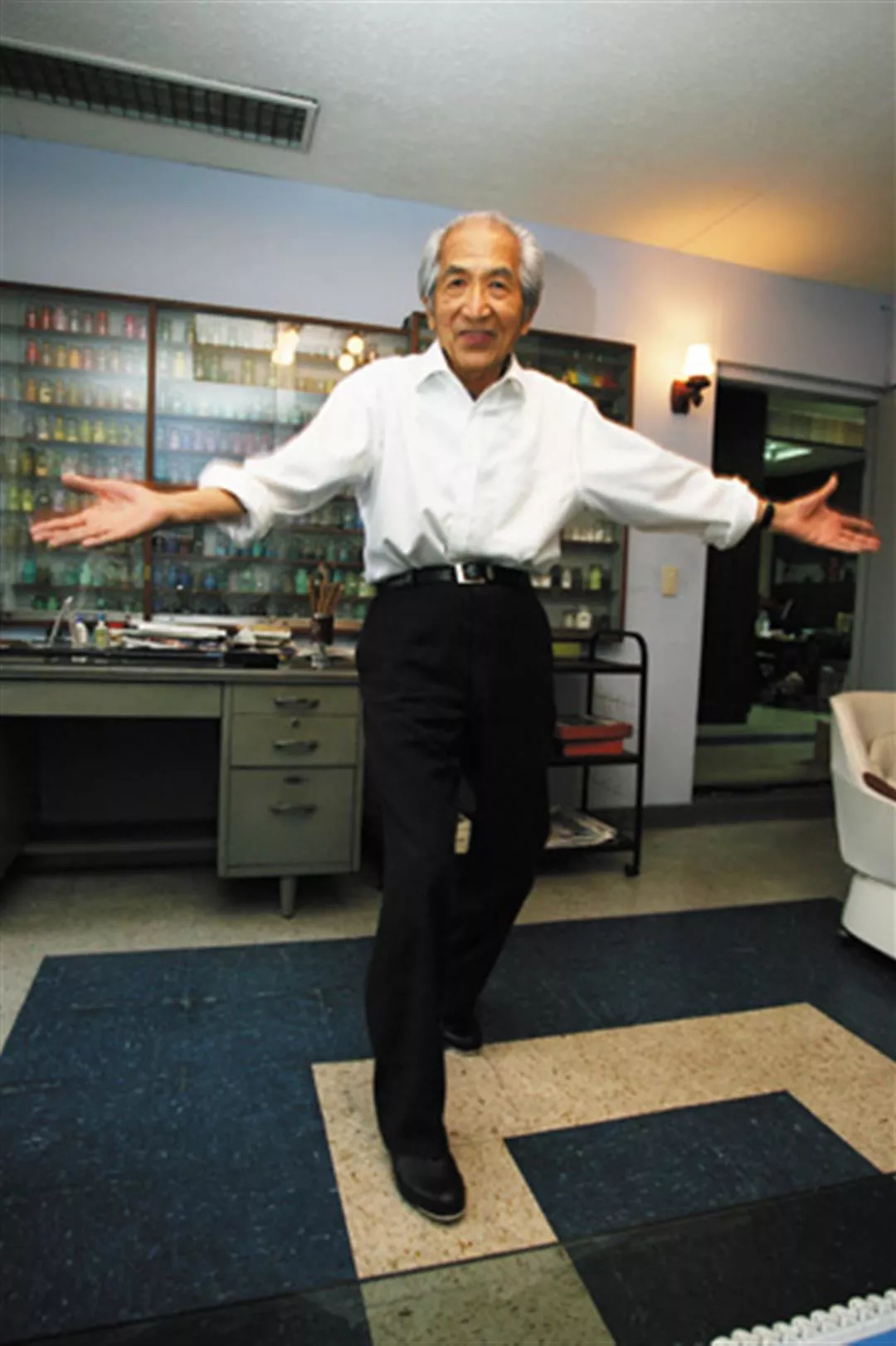

Honored as Taiwan's "master of dis-temper painting," Lin Chih-chu has devoted his life to extending the legacy of this noble and singularly beautiful genre. Made by heating glue, mixing in pigment, and then spreading the mix in layers on silk, works in distemper (or glue tempera) attain a colorful exuberance that is rare in Chinese painting. Lin's own distemper paintings show meticulous attention to composition and color. Their elegant aura has earned him a reputation as a "magician of color." But this 90-year-old painter has more up his sleeve: when he recently received a National Cultural Award, he brought the house down by tap dancing.

At his Japanese-style residence on Liuchuan West Road in Taichung, Lin's studio table is covered with containers of natural minerals, chemicals, clays and other materials. Here Lin makes a detailed explanation of Autumnal Colors, one of his newest works:

"In this still life, the visual focus is on these three red persimmons, which I have painted in fine detail. The angles and colors of the fallen leaves serve to emphasize the main subject. They can't be too dominant or too weak. The leaves have a rough surface texture, so I've added some minerals to the paint to get that across. Where the leaves meet, there is a crisscross of vertical and horizontal lines, which gives a sense of depth. For a contrast of dark and light, most people think that you should add black to show darkness. But I don't use it because in a scene lit by sunlight there is no black, only dark shades of color...."

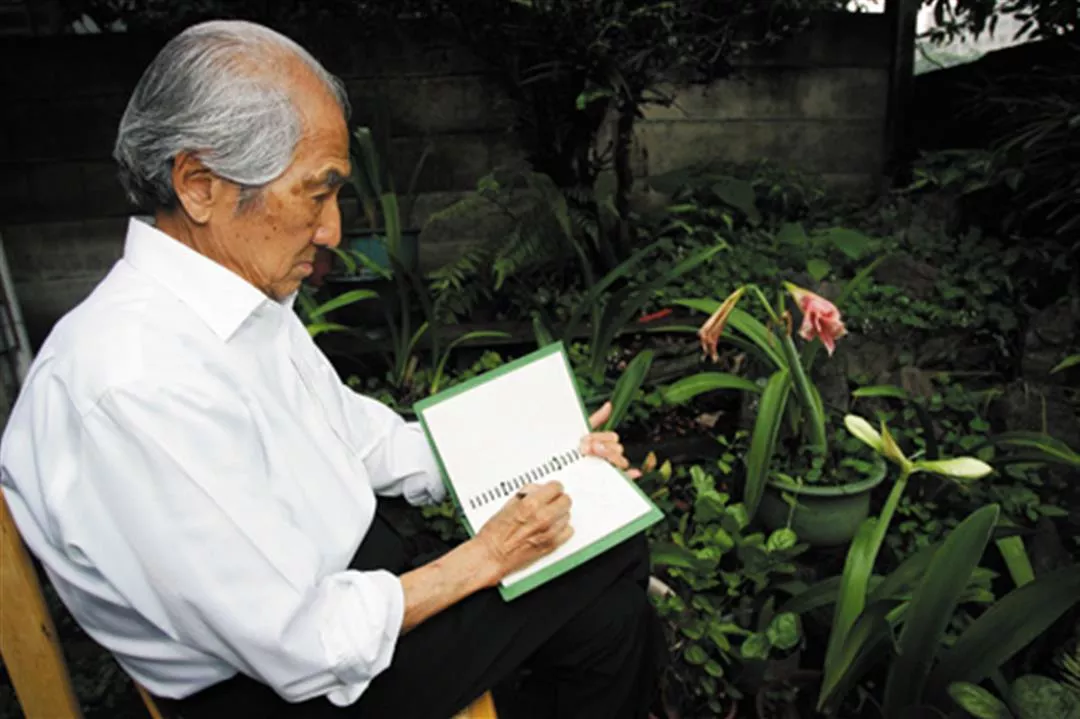

Outside the window sparrows twitter under a mango tree. Lin loves to paint flowers and birds. For a view of birds in their natural environment, he specially stuck up a piece of white paper in the window of his studio, cutting two removable slits to serve as eyeholes. So as to get realistic views of the caged birds in his garden, he opens the eyeholes and quickly sketches the birds, which are never aware that they are secretly being watched. Then he closes the eyeholes. Through the whole process, the moods on both sides of the window remain totally carefree.

Lin's relaxed demeanor stems--apart from his innate love of nature--from his upbringing and education. He suffered far fewer hardships than most Taiwanese painters of his generation.

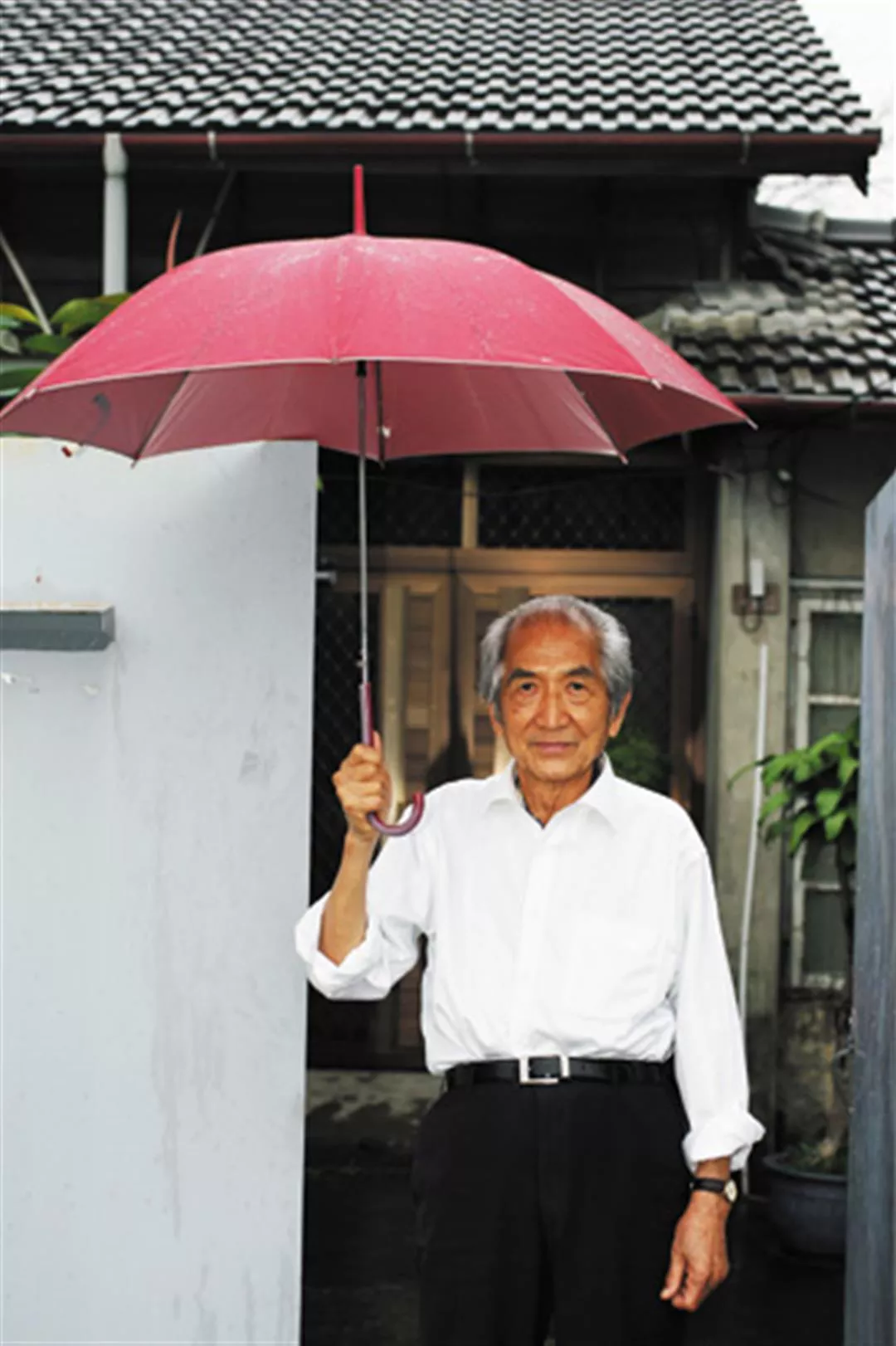

When Lin got a job teaching art at National Taichung Teacher's College in 1946, he moved into this Japanese-style residence on Liuchuan West Road in Taichung. Although he left for the United States upon his retirement, he still lives here when he returns to Taiwan to visit.

Little overseas student

Lin was born in 1917 in Shangfung Village of Taya Township, Taichung County to an affluent farming family. His father Lin Chuan-fu was a major landlord and the first mayor of Shenkang Township during the Japanese era. Their home--Fucu or "house of wealth"--was a sanheyuan courtyard compound that blended Chinese and Western architectural styles. The raised ridge and upturned eaves of the roof, and the pillars, beams and walls of the house, were all exquisitely worked and beautifully painted. From a young age, he enjoyed leaning over the compound's railings and watching the birds and flowers.

In 1923 Lin began his studies at the Taya public school. When he was about ten, he would draw separate, slightly changing images of people on the empty corners of the pages of his textbooks. By then moving his thumb along the outside corner of the book, the individual drawings appearing in rapid succession would look like a single moving image.

"Every morning, I would awake among the collective song of Japanese white eyes, Chinese bulbuls, and oriental turtle doves, and through the seasons I would smell the different flowers in bloom. I would think that I wanted to create something as beautiful as the blooming flowers and the gyrating calls of the birds--that I would paint."

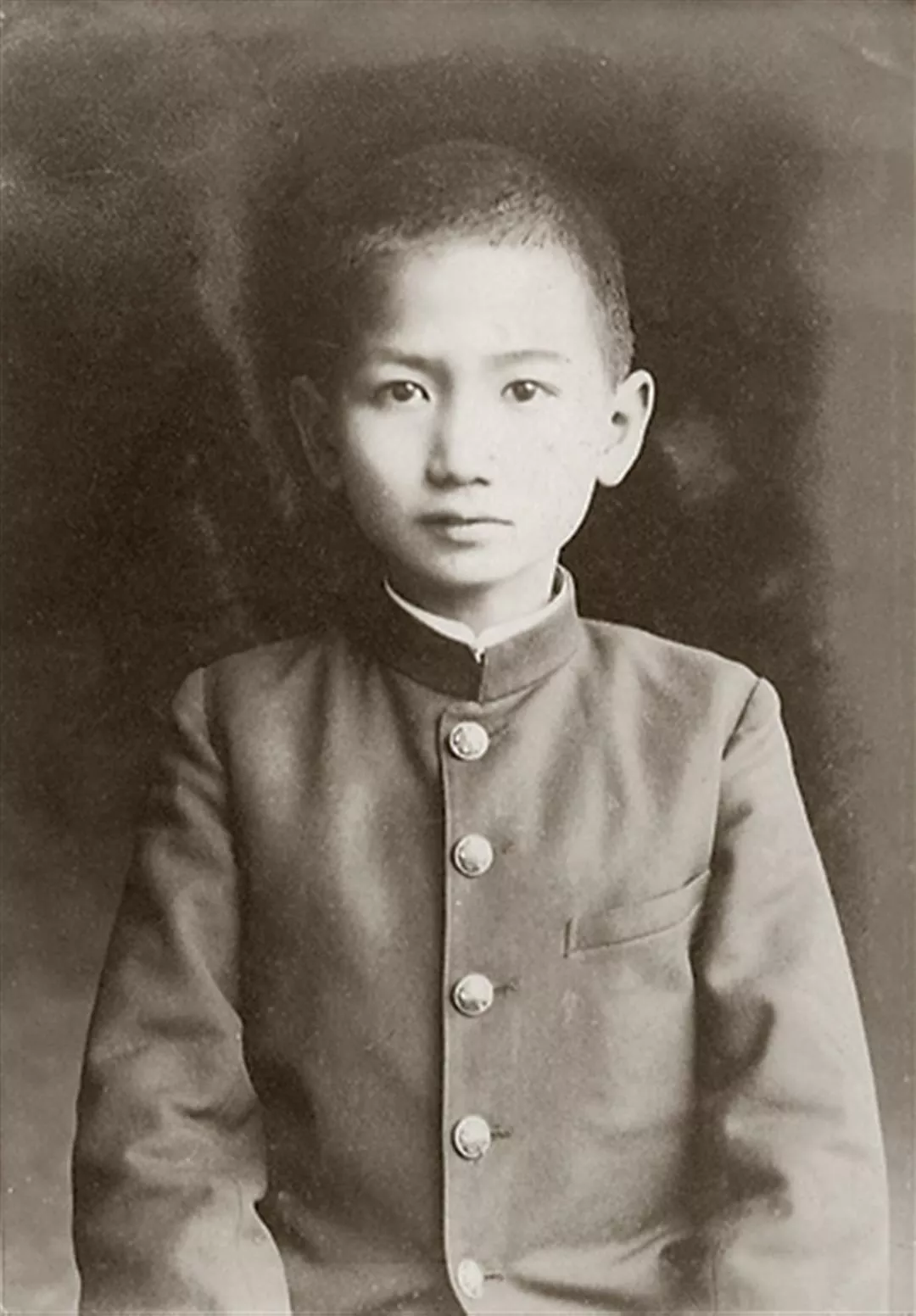

During the Japanese era, talented Taiwanese typically studied medicine or law. Lin's father stressed education to his children, and hoped Lin Chih-chu would become a doctor. To get a head start, he was sent to Tokyo for his studies at the tender age of 12. When Chih-chu boarded the steamship Yamato Maru, embarking on his life journey, his father didn't realize that his much-loved third son was in fact embarking on a life voyage that would lead to a career in art.

He completed his elementary education at a school in Tokyo and the following year passed the entrance exam for a Japanese junior high school. At the completion of junior high school, Lin faced a major decision: Take an exam for medical school in accordance with his father's wishes, or follow his own heart and test for art school.

"If I became a doctor, I would have to be in the hospital from morning to night and face sad-faced patients day after day. It was an unappealing way of making a living!" It was then that Lin decided to pursue a career in art.

Lin, who has led a charmed existence and is a connoisseur of life, enjoys tap-dancing. When he was given a National Cultural Award this year, his routine brought the house down.

The old sharecropper

In 1934 Lin passed the entrance exam for the oriental and Western painting department of what is today Musashino Art University. At the time the department had four professors: Togyu Okumura, Hoshun Yamaguchi, Aritsune Hattori and Sokyojin Kobayashi. In turn they would each teach the students a week at a time. In order to strengthen his ability to draw from nature, Lin, starting freshman year, would complete a drawing of a different plant ever day. He also kept a pocket-sized sketchpad with him wherever he went, and he would sketch during his commute.

Apart from painting, Lin also had a great love of Western literature. Tolstoy gave him deep insights into the nature of human existence. Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky's compassionate and forgiving exploration of human nature, struck an even deeper chord with Lin, who displayed a strong moral sense from a young age.

Lin was deeply influenced by the respectful way that his father treated people, and this "third young master" (as servants called the third male child of a wealthy family) early in life came to understand the hardships borne by the middle and lower classes. During summer vacation when he was 17, he came back from Japan to visit his family. One day, when he was walking along the narrow embankment between paddy fields, an old sharecropper approached from the other side. When they almost met, the old man deftly placed one foot onto the wet ground and turned his body at an angle to allow Lin to pass. But this "third young master" had none of a landlord's sense of entitlement. He only thought: "Can it be right for the elder to make way for the junior?" So he too put one foot down in the water and twisted his body aside as he squeezed past the old man. At first the old farmer seemed taken aback, but then his smiling face radiated approval and appreciation. That smile imprinted itself in Lin's mind.

Three exquisitely rendered persimmons were the focal point of Lin Chih-chu's recent work Autumnal Colors. Lin added some minerals to the leaves so as to better capture their rough texture.

A student of Kodama Kibou

His compassionate nature and exposure to literature prodded in Lin a concern for society's vulnerable that was revealed in his art. In the 1935 work The Remains of the Day, he painted back alleys and dilapidated old buildings that normally wouldn't attract people's notice, using a drab color scheme to depict the life of the poor. At a school ball, he and classmates wore beggars' clothes, parodying the upper classes for their oppression of the poor and their ugly pursuit of filthy lucre.

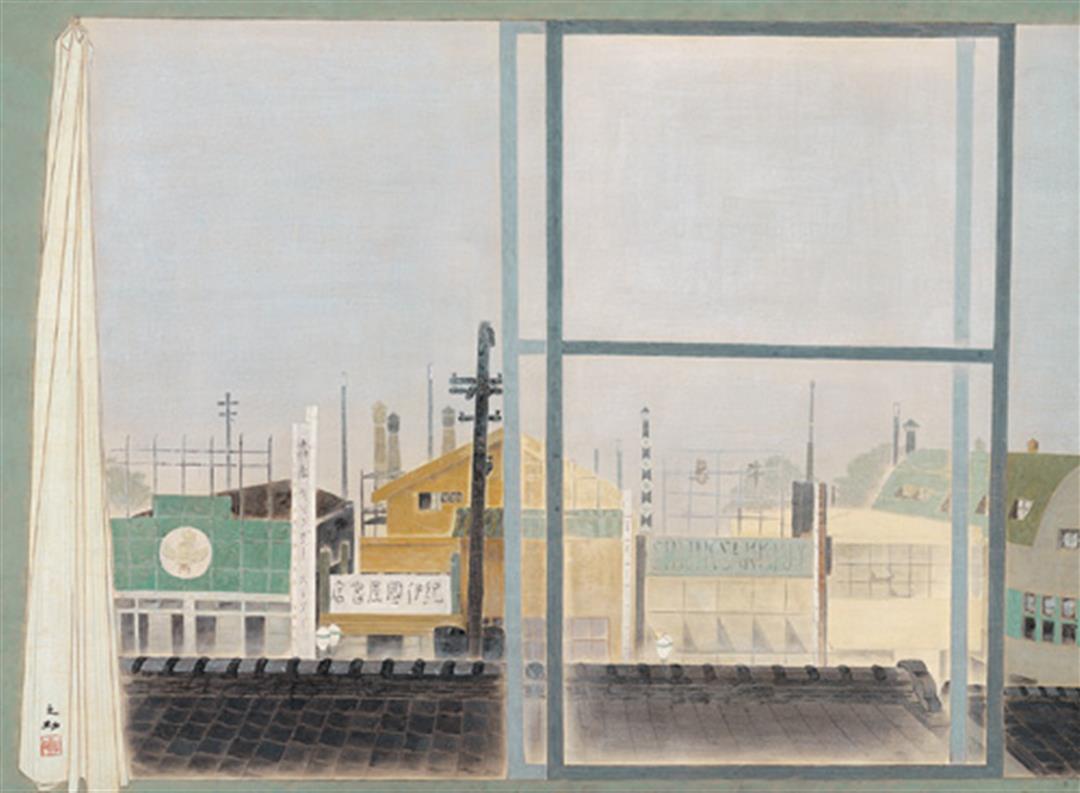

During his time at art school, most of his work drew from scenes that he was familiar with in life. He painted his 1937 work Shinjuku Panorama at Nakamuraya, a famous restaurant that offered good views of the streets of the Shinjuku neighborhood from its second floor. In the following year's Dusk, Lin painted the central courtyard of the house next door to where he lived. It was selected for the second Shinkou Exhibition of Japanese art.

After Lin graduated in 1939, the famous Japanese painter Kodama Kibou (1898-1969) took him on as a student at the recommendation of Lin's friend Chen Yung-sen. Although Kodama's academy was a private institution, his students were all set on becoming professional painters. Highly motivated and self-disciplined, they placed high expectations on themselves.

Not long after Lin entered Kodama's academy, his work Rice Shop was accepted for the 26th Nisshoin Exhibition, and was sold to a famous restaurant "Art Talk Garden" for ¥150, which was about half of a teacher's annual salary. The same year, his painting Short Break won a prize in the Kodama Kibou Academy's fourth annual awards. Although these works were similar in theme to what he had produced at his previous school, they showed more refinement, control and cleaner lines.

In the spring of 1940, Lin returned home to Taiwan on vacation, at which time his mother took upon herself the role of matchmaker. She arranged an elegant meeting between him and Wang Tsai-chu over a game of chess. It was love at first sight and the two were promptly engaged.

Recalling that game of chess that took place more than half a century ago, Wang says: "Ever since I was a little girl I had revered painters. I was attracted by artists' colorful and creative lives. When I was in Japan early in my marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Kodama warned me that a wife of a painter needed patience and determination to endure hardships. But because Chih-chu is so considerate and optimistic, I feel as if I've been under his protective care all my life."

Born to the gentry, Lin was sent off to study in Tokyo when he was just 12. His father hoped he would study medicine and become a doctor.

"Cool Morning"

After becoming engaged, Lin returned to Japan. Feeling greater pressure to establish himself in his career with his impending marriage, he decided to challenge himself by participating in an art competition sponsored by the Japanese government. Because 1940 was the 2600th year of imperial rule in Japan, the exhibition that year was known as the "2600th Year Celebratory Exhibition," and it was expanded in scope.

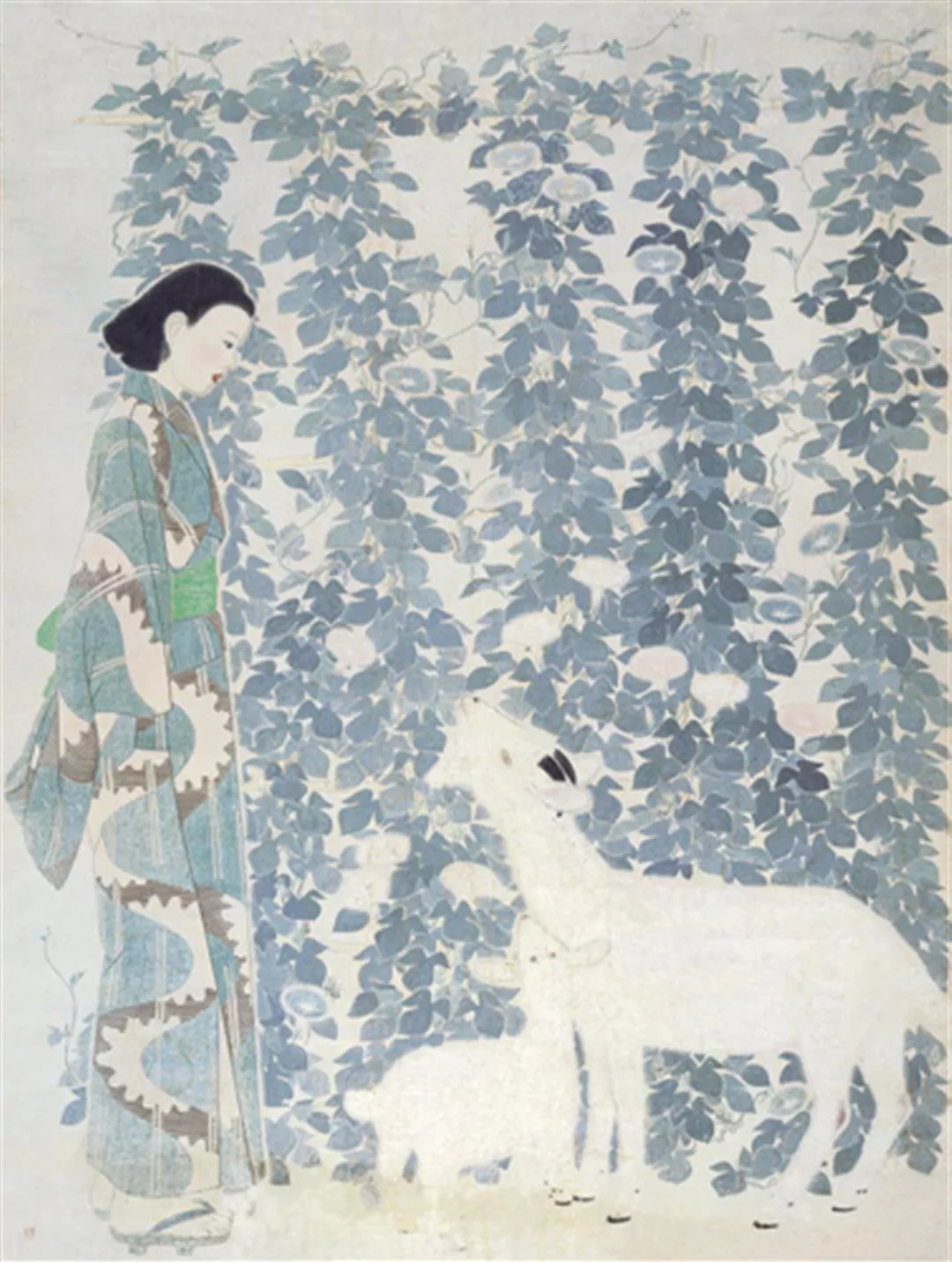

After deciding to participate in the competition, Lin struggled for many days without being able to come up with a suitable subject or design. One day, he woke up early in the morning and put on a coat to go out for a walk. The scene that greeted him as he stepped out the door he found deeply compelling: Gentle daylight filtering through the light morning fog, softly illuminating the trellis of morning glories. The pink and purple of the blooms and the bright green leaves of the trees were suffused with a layer of light gray, giving them an otherworldly beauty. Immediately he ran to his studio to paint. He then decided to paint two white goats next to the trellis, and inserted his fiancee into the composition as the central figure.

"The preparatory sketches for Cool Morning took one month to prepare, and application of the colors took two. In the morning I'd drink miso soup, and in the afternoon I'd drink more of the soup with white rice. That's what I had day after day." He spent the summer sweating in a small rented room. When he encountered difficulties, he would dress up and go to a favorite restaurant to enjoy a fine meal. Spirits lifted, he'd then return to the studio to paint. After a while, friends who saw him dressed in his finest clothes would know that his work wasn't going well, whereas if he left his house for a bite to eat while whistling, dressed casually with messy hair, then all was going smoothly.

After a summer's hard work, Cool Morning was finally completed, and Lin hired a truck to move the painting, which was about three meters high and two meters long, to the exhibition. He then happily packed his luggage and returned to Taiwan to prepare for the wedding. Before departing he figured that the selection committee would probably make their decision while he was in Taiwan, so he asked his landlord, who ran a rice shop, to send him a telegram when the notice came to tell him whether he was selected or not.

Much to Lin's surprise, the landlord laughed at the chutzpah of this youth who had just graduated from art school to suppose that he might be selected as one of the winners of the competition and joked: "If you're selected, I'll walk backwards all the way from my shop to Shinjuku." On the day before his wedding, Lin received the landlord's telegram that his work had been selected. It was the ideal wedding present. Even now, 60 years later, Lin gets very excited in the retelling of this incident.

In 1965 Lin opened Peacock Coffee on Kuangfu Road in Taichung. Ever attentive to coordinating colors, he made a special trip to Tokyo to purchase the establishment's coffee cups, which he still treasures today.

Passing the torch

In December 1941 Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, and subsequently FDR ordered the freezing of Japanese assets in the United States and the plan to put people of Japanese ancestry into internment camps. It was a nervous time, and Lin's Taiwanese friends and family begged Lin and his wife to return to Taiwan. Even though Kodama Kibou urged him to stay and continue working to advance in the Japanese art world, Lin decided to accompany his pregnant wife home.

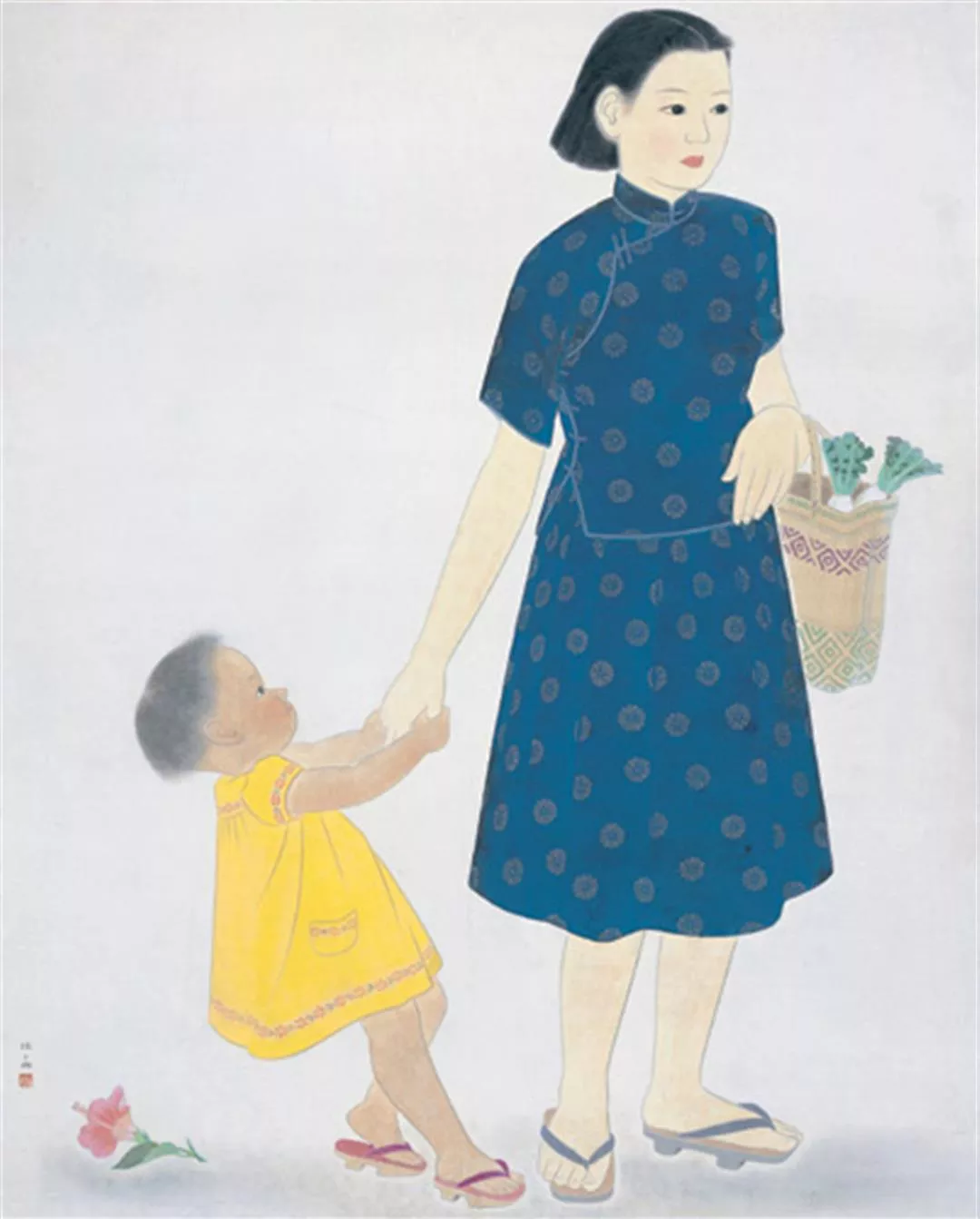

Upon his return, he began to plow the fields of Taiwanese art. He decided to test his mettle by participating in the Taiwan Governor-General's Exhibition, and in consecutive years Mother and Child and Good Day took first prize honors in the Japanese art category. He also won the exhibition's overall award.

Yet with World War II raging, people's financial wherewithal was limited. Though he was a child of the gentry, the policy of rationing forced him to roll up his sleeves, don a farmer's hat and plant rice. Because it was so unusual for a landlord to work the fields, a Japanese newspaper even came to interview him. Lin would farm from sunup until sundown. And he brought fields and wilds, scenes of farmers at work, and waves of golden rice into his art.

After the war, Lin moved to Taichung, and in 1946 got a job teaching art at Taichung Normal College. Because painting in distemper wasn't in Taiwan's fine arts curriculum, he taught drawing and watercolors instead.

Through the 34 years of his teaching career, up until he retired in 1980, Lin would pass along distemper painting techniques when he came across particularly talented students. Apart from not charging tuition, he would also provide them with the use of expensive pigments, painting equipment, and a painting studio. Master and student would spend hours researching the genre, which has complicated techniques that are very time consuming. Among the many talented students he taught were such figures as Huang Teng-tang, Chen Shih-chu, Lin Hsing-hua, Shih Hua-tang, and Liao Ta-sheng. They would all go on to establish themselves as successful artists with their own styles.

There's a brush in this can to meet any need of a distemper painter.

What's in a name?

For the 1946 Taiwan Provincial Art Exhibition, Lin secured the job of judge of the Chinese-style paintings. At the time paintings in distemper, though called "dong yang hua" ("eastern ocean," meaning Japanese, paintings), were included in the category of "Chinese painting" alongside traditional ink-wash painting. This ignited decades of controversy in Taiwan art circles about what constituted true Chinese painting. Later, for the fifteenth year of the provincial competition, Chinese painting was divided between "Section One" for traditional ink-wash painting on scrolls, and "Section Two" for framed works, including realistic paintings in distemper.

This form of distemper painting the Japanese had borrowed from the fine-brushwork, colorful paintings of Tang-dynasty China. The methods and style belonged to the northern school. Although quite different from the southern school, which made rather restrained use of color, the northern school was nonetheless part of the heritage of Chinese painting. But after the end of World War II, a great many ink-wash painters moved to Taiwan from the mainland who believed that distemper paintings were "Japanese and not authentically Chinese." They didn't allow painting in distemper to be included in fine arts curricula. This touched upon sensitive areas about "who favored China" and "who favored Japan" and about "the natives who had been colonized by the Japanese" and "the post-war conquerors from China."

At the 28th annual exhibition, the organizers suddenly cancelled "Section Two" of Chinese painting, and refused to accept works in distemper. It caused a big stir, and prompted a lot of debate within the native Taiwanese art world about what to call this style of painting. Some advocated changing the name from "dong yang hua" to "new Chinese painting" or "modern Chinese painting." It was hotly argued.

In 1977, in order to get around the issue of a proper name, Lin began to use the Western method of basing the categories around materials. Just as there was "oil painting" (which used oil paints) and "watercolors" (which used water based paints), for painting in distemper, which employs glue, Lin chose the phrase "jiao cai hua" or "glue-color painting." The terminology was gradually accepted by the island's art community, thus resolving a major controversy in the history of Taiwanese painting.

After establishing the Central Taiwan Fine Arts Association in 1954, in 1981 Lin established the Taiwanese Distemper Painting Association, which helped to further secure the status of distemper painting in Taiwan. This eventually had an impact on the provincial competition. In 1982 they eliminated the Chinese painting division in favor of "ink-wash painting" and "distemper painting." Lin's fight on behalf of the genre had finally borne fruit.

In 1985, Tunghai University in Taichung hired Lin as a professor of painting in distemper. For the first time in the 100 years of the art in Taiwan, it had formally entered a university fine arts curriculum.

In 1941 Lin returned from Japan and began plowing in the Taiwanese art circle. In 1943 his Good Day won the Sixth Annual Taiwan Governor-General's Exhibition in the distemper category, which was called "eastern ocean" or Japanese-style painting.

Leaving the ivory tower

Apart from actively promoting the art of distemper, in the 1950s Lin established Chinglung Publishing in order to strengthen art education. It stood at the forefront of a trend to get artists to edit and publish elementary art textbooks.

"True artists have to take upon themselves the work of cultivating an appreciation and concern for art among the general population." For a set of children's art textbooks, he wrote every word and personally selected sample works from provincial children's art exhibitions.

Lin published junior high school and high school textbooks. And this difficult and far-reaching work to broadly sow the roots of art also garnered the support of fellow faculty members, including Wang Erh-chang, Cheng Shan-hsi, Chang Hsi-chin, and painter friends Yang San-lang, Ma Shui-lung, Hung Jui-lin, and Lin Yu-shan, who all contributed model works for the books.

In 1967 Lin also led fashion by leaving the purely academic realm of the ivory tower and accepting a job at Shih Chien College of Home Economics (now Shih Chien University) to teach coursework in "color education" for 11 years. During this period, he wrote Matching Clothing Color and Colors and Matching Colors. These books employed lively layouts, so that readers could at one glance immediately understand aesthetics of color in fashion. And by introducing conceptions of "like colors," "matching colors," and "complementary colors," he gave readers a means to apply these ideas flexibly in their own lives.

The birds and flowers in a Japanese-style residence make fitting subject matter for this old painter.

A life of good fortune

Among the various ways that Lin Chih-chu brought art into everyday life, his running of a coffee shop most attracted people's notice. A coffee lover, he needed only to catch a whiff of brewing coffee to find his spirits lifting. So as to bring back to his homeland the coffee house culture that he experienced in Tokyo, he opened Peacock Coffee on Kuangfu Road in Taichung in 1965.

At a time when Taiwan's society was still closed and conservative, Peacock Coffee was like a breath of fresh air. Works of art adorned the walls, and carefully selected music played on the stereo. Lin and his wife had even specially chosen the coffee cups, which they brought in from Japan after much thought about matching colors. The cups were white on the inside and blue on the outside and the saucers were blue; both of them had a gold pattern of plants and flowers.

"When the white-inside, blue-outside coffee cups were eight-tenths full, the extreme contrast of blue and brown accentuated the contrast of color and light and naturally drew people's eyes," Lin recalls in great detail. "A dividing band of white around the mouth of the cup made the color of the coffee appear even more beautiful by heightening the contrast with the gold. It made the coffee look richer and more delicious."

With an owner so attuned to aesthetics, it was no wonder that Peacock Coffee was, up until it closed in the late 1970s, the cultural venue most representative of greater Taichung. It was the central Taiwan equivalent of Stars Cafe on Taipei's Wuchang Street.

Although the Lins have been living in the United States for many years, they return to Taichung every year to catch up with old friends. Lin's wife Wang Tsai-chu warmly welcomes guests and at the same time plays the role of database. When trying to put a date on past events, Lin time and again turns to his wife to make certain.

"He's a very impatient person since he uses all his patience in his art," says Wang, who has an elegant air about her. "To make an analogy to musicians, I would say that he definitely isn't the fierce and serious Beethoven, but rather someone more akin to the leisurely Felix Mendelssohn."

There is a sudden cloudburst, and willows on the riverbank blow wildly in the wind. But inside there is a clear rhythm. Lin puts on just-purchased tap shoes, his hand clutching a gentlemanly cane, as he concentrates on the beat and lithely taps out his routine. Romantic, elegant, and happy, Lin's very presence brings joy to this old studio, as have his life of good fortune and the luscious colors of his distemper paintings, from which people find it so hard to turn their eyes.

With its carefully considered color scheme and lively composition, Lin's 1996 work Lichun exudes elegance.

Lin's studio is cluttered with all manner of natural, chemical and mineral pigments.

From a young age, Lin had an understanding of the hardships endured by the middle and lower classes. While attending Musashino Art University, Lin (second from left) and classmates wore beggars' rags to a formal school celebration, ridiculing the upper classes for their ugly pursuit of mammon.

Cool Morning, a composition that centered on Lin's fiancee, was entered in a 1940 exhibition celebrating 2600 years of imperial rule in Japan.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)