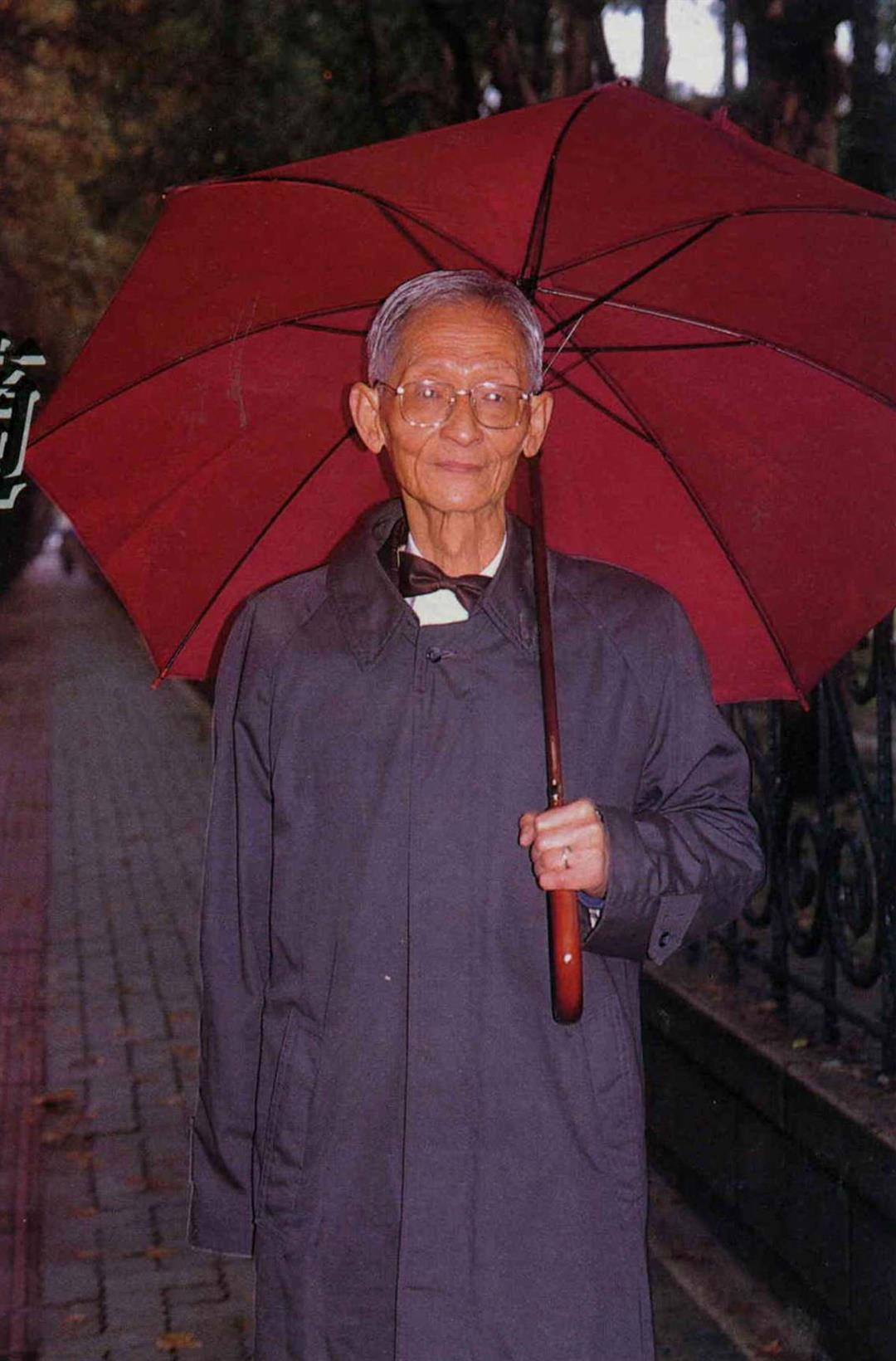

Lao Ssu-kuang on Leisure

orally dictated by Lao Ssu-kuang/edited by Wang Jiafong / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Christopher Hughes

April 1998

Some indication of the emotions implied by the Chinese word for "leisure" (xian) can be gained from the construction of its ideogram, which consists of a moon inside a window. This seems to be somewhat removed from the definition of leisure as just being something that is opposed to work, as found in efficient modern societies. What then are the ideas behind the Chinese concept of leisure? What role does leisure play in Chinese life? Let us ask Professor Lao Ssu-kuang, an expert on Chinese and Western philosophy.

If we want to discuss Chinese leisure, we must start out by understanding its cultural background and the tradition of thought that is most representative of its ethos.

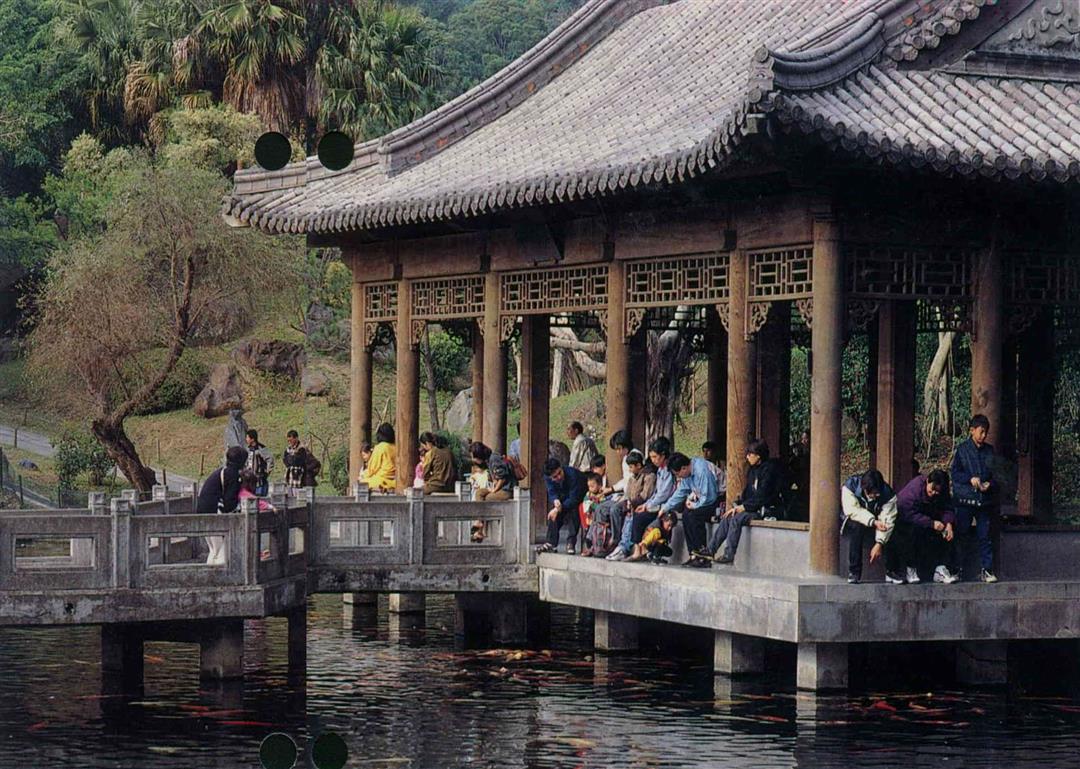

If you are not a fish, how do you know the fish are happy? Zhuangzi advocated "watching transformation" and transcending the material world rather than establishing order or gaining knowledge. This kind of tranquil contemplation is in the realm of the "aesthetic self.".

Three realms of the self

Any discussion of this ethos should start out from the "realms of the self." The most fundamental realm of the self can be called the "constructive consciousness," which involves laying down rules and standards and establishing social order. This in turn demands certain values, as found for example, in the Zhou dynasty culture, which was followed by Confucianism in the world of philosophy. In this realm, the individual is required to perform the constructive functions of transforming nature and ordering human affairs. Speaking in general terms, this can also be called the "moral self."

There is another realm of the self, though, which is not concerned with establishing order but wants to grasp certain knowledge and understand the principles that govern things. Representative of this tradition is the thinking of Socrates and Plato, which has been central to the European tradition right up to the appearance of modern philosophy. This is what we call the "cognitive self."

From an historical perspective, the above two realms of the self seem to be in the mainstream. They arise from the most important affairs of human life, namely how we understand the exterior world and how we establish order. The moral self gives birth to a system of rules, the cognitive self gives birth to scientific consciousness. But human life does have other facets. The most obvious of these is artistic activity, which involves neither the establishment of order nor the grasping of knowledge. Pre-Qin-dynasty Daoism is representative of this realm of the self in China.

If you are not a fish, how do you know the fish are happy? Zhuangzi advocated "watching transformation" and transcending the material world rather than establishing order or gaining knowledge. This kind of tranquil contemplation is in the realm of the "aesthetic self.".

Daoist art

There has been much discussion of Daoism, but most of this has been about the transformed version that developed after the Han dynasty and which had several branches. One of these was the art of Huang-Lao, a kind of strategy of government that politicized Daoist thought, making it into a way of ruling based on the idea of letting society recover its vital energy through rest. Another branch was "religious Daoism."

Religious Daoism is quite different from philosophical Daoism, and has its own separate origins. These can be traced back to the northern coastal culture of China and the practices of medicine men. The spacious and misty marine atmosphere created a very mystical ethos for this school, closely related to the ancient witchcraft traditions of exorcism and healing. This developed into the Dao of longevity and alchemy, and finally into religious Daoism.

The blurring of philosophical Daoism with religious Daoism occurred after the Han dynasty. It seems that all of the religions in the world tend to look away from the present world, and stress the other world. It is only religious Daoism that advocates prolonging the life of the body and wants to directly transform it. This is very special. It also looked to the ancients for support. Although we know that Han-dynasty religious Daoism was very fragmented when it began, by the end of the Eastern Han it had become fully developed, and Laozi and Zhuangzi had been nominated as its predecessors.

If we want to talk about the culture of leisure in Chinese tradition, it is back to these pre-Qin Daoists that we must turn, and not to the religious Daoism that came later.

Life consists of "action" and "rest." As well as striving to make a living, returning home for a break and a chat is really one of the great pleasures of life.

Zhuangzi on leisure

Leisure constitutes another realm of the self, and this is something expressed in Zhuangzi's section on "Unburdened Roaming" (xiao yao you). It is an artistic and emotional realm, and philosophical Daoism gives it a theoretical foundation. Its most important explanatory ideas can be found in the "Inner Volumes" of Zhuangzi, describe how the things of the world, including the human body, all arise from the cycle of birth and destruction, and are determined by natural causes. This process is what Zhuangzi calls "transformation" (hua), which has a connotation of creativity. To Zhuangzi, the foundation of knowledge is actually a game we create for ourselves. We select a few things, create our own theories, and finally come up with a world view. Other people might produce an alternative one.

When you look in detail at this theory, it can become very complex. Put simply, it can be found in Zhuangzi's section "On Ordering Things" (qi wu lun). Here Zhuangzi says that our knowledge about nature and about the truth and falsity of opinion is entirely based on criteria that we choose for ourselves. No matter what people might say, however, the transformation of the world carries on according to its own internal principles.

Take human life for example. From nothing you become something, go through the process of your existence, and are then finally exterminated. This is the natural "Way" of your life. Wanting to make an effort and change things, as in Confucian thinking, is meaningless and unnecessary.

Zhuangzi's main message is thus that all things should return to the "Way" of nature. Human intervention is a mistake and amounts to fruitless labor. The self should thus just transcend bodily sensations and emotions and tranquilly observe the transformation of nature. This is the "watching transformation" (guan hua) that Zhuangzi advocates. In this way, the truly wise person can transcend the objects of the world of change, remaining unaffected by them and refraining from acting on them, as positively advocated in the section on "Unburdened Roaming."

The aesthetic self

So Zhuangzi wants neither to achieve knowledge nor to establish order, only to appreciate nature in the process of transcending one's own existence. This kind of appreciation becomes a kind of "emotional state." When I was systematizing Chinese philosophy, I called this the "aesthetic self," because feelings of transcendence are quite distinct from those of the moral self and the cognitive self. There is no such term in tradition.

This realm of the self obviously does not develop science or establish order. What it can give rise to, though, is art.

Despite getting distorted and mixed up with religion and politics in the Han dynasty, when this philosophy was applied to art it produced a type of emotion that could be enjoyed as a value in itself, not as an instrument for achieving something else.

Chinese painting was originally instrumental, with the portraits and narrative paintings of the Han dynasty being used for moral and didactic purposes. When landscape developed to its peak and used natural scenery as a medium to reveal living emotions, though, it was the Daoist "aesthetic self" that was being expressed.

People often say that when Chinese intellectuals are living a normal, successful life, they become Confucianists with the ideals of setting the country to rights and pacifying the world. When they have to deal with practical affairs and get hold of power, they use Legalism to think up ways of controlling others and consolidating their position. If they are failures, though, they turn to the life of the hermit and become Daoists.

This seems to be saying that Daoism is the retreat of the loser. However, if we make comparisons with other cultures we can be clear that, under the influence of the spirit of the Daoist "aesthetic self," the artistic realm contains another concept of value that is not necessarily a defeatist philosophy.

Kant's sublime

When we are talking about emotional issues, we must be clear that what we are talking about is the "aesthetic self." We are not concerned with moral or objective knowledge here, and not discussing "imperatives" or "the truth." The aesthetic self is not concerned with the realization of responsibility or values. It is linked instead to aesthetic theory.

In the human sphere, apart from seeking knowledge and the good, there is also the quest for beauty. This can be related to our "three realms." There are plenty of theories throughout history for the first two realms, but relatively few successful ones for the third. This is because it is a very difficult subject to discuss.

The three critiques of Immanuel Kant represent a watershed in modern Western philosophy. The Critique of Pure Reason is concerned with problems of knowledge. The Critique of Practical Reason is concerned with questions of morality. The third is the Critique of Judgment, which is about artistic and aesthetic problems.

The arguments in the first two of these critiques are very clear, but the third is laboriously written and far from clear. Here, Kant stresses the idea of the "sublime." By this he means that, as well as there being the kind of beauty that is just a pleasure to look at, there is also a kind of grand beauty that leads people to divine feelings, and has no instrumental nature. In the process, the observer becomes aware of his own limitations and tries to overcome them. A calm sea and a warm sun make a beautiful scene. But in observing a storm, a person transcends the vague idea he has of himself and is led towards divine sentiments. Such is the nature of great tragedy.

Calmly watching and freely wandering

Kant's idea of the sublime touches on the most inner self and develops an awareness of one's limitations, producing a kind of transcendence. But this cannot cover the whole of the realm of beauty. The Chinese idea of leisure is exactly its opposite.

If our lives are limited, apart from understanding these limitations, we must also come to "appreciate" them. The realm of leisure does not seek to transform the world. It allows us to remain within this world and to calmly observe and appreciate it.

You can look at the beauty of everyday life and observe and understand all the transformations of nature, including the sublime element. But you cannot put yourself into them, and must deal with them without any idea of profit and loss. This is the realm of what the Daoists call "unburdened roaming."

Kant analyses the source of beauty in terms of the actions of the inner self. The "unburdened roaming" of the Daoists, though, is more of a symbolic metaphor used to describe the phenomenon. When the Chinese talk about leisure, it is basically this kind of thing.

For example, the stanza "Cock sound thatch roof moon, person trace bridge frost," certainly does not consist of logical language. There are even no verbs. All the words are nouns. But Chinese people can be clear enough about the realm in which it is located. The poems of Tao Yuanming reveal most of all the taste for leisure, but he does not want to justify it, only to express a certain kind of ethos.

Confucian responsibility

When we see the sentiments of leisure as part of Chinese tradition, there is still a question that needs to be answered. How is the enjoyment of leisure related to the other parts of life? How can people find a life of leisure? After all, people do have certain responsibilities and obligations in real life.

The problem can actually be restated as this: How should we arrange the different demands of life?

In terms of tradition, Confucianism moralized art from an early stage, making it a tool of ethics. For example, ritual music is supposed to be for pedagogic use rather than enjoyment. Under the impact of Confucianism, the Chinese gentleman could appreciate leisurely sentiments, but could very rarely talk about them in a positive way.

Song-dynasty Confucianism took relatively little notice of art (with a few exceptions, of course). It thought that the affairs of human life were very serious, and that pursuing leisure was a kind of indolence and waste of life. Cheng Yichuan, for example, felt that all books that were not morally beneficial were superfluous.

The Confucian realm is one of responsibility. Yet even in this limited life, there is still the need for cultivation. So Daoist sentiments of leisure still have a certain significance. This is the meaning of "treasuring life" (gui sheng) in the philosopher Yang Zhu.

Action and rest

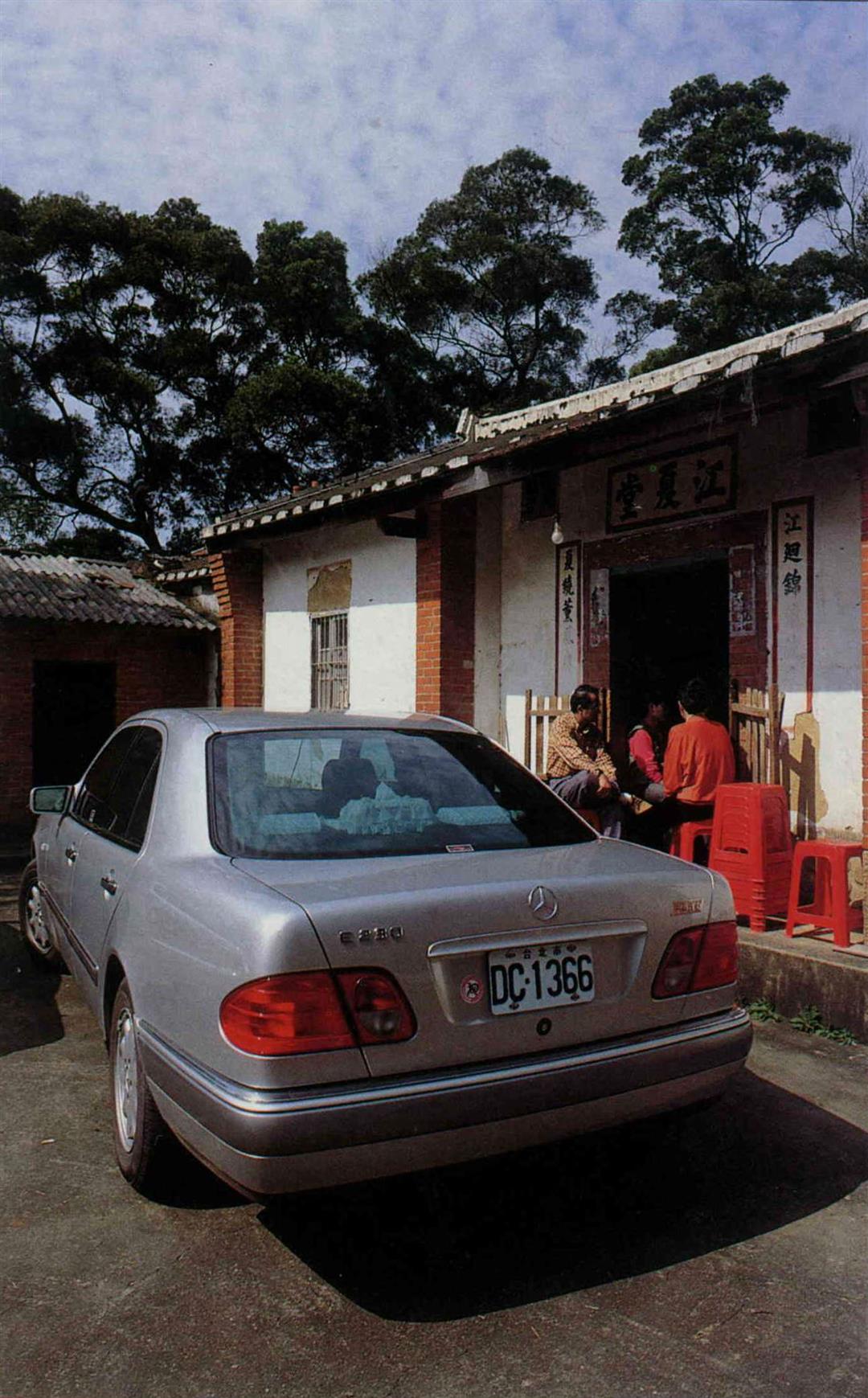

If you do not talk about philosophy but look directly at life, it entails the two aspects of action and rest. The former involves knowledge, order, and responsible ideals. But people cannot live in a perpetual state of anxiety and exhaustion. To maintain a life of sufficient "action" requires a certain amount of cultivation. The stage of "rest" is when you develop vitality and recover the spirit.

It can thus be said that leisure is one of the necessities of life.

Zhuangzi took self-cultivation to extremes. In his section on "The Human World" he talked about a gigantic tree. Everybody was amazed by it, except for a famous carpenter. When his apprentice asked why, the carpenter explained that the tree was of such poor quality that if it was made into a boat it would sink, and if it was used for a column it would be eaten by worms. It was precisely because it was useless that it had lasted to such a great age. If it could have been used, it would have been cut down long before then.

So Zhuangzi thought that anything useful would be made into a tool, and that the self should not be so instrumentalized. It should transcend the material world and roam unburdened. In the end, though, it is the Daoists who provide us with the most extreme example of taking the aesthetic self seriously. The Confucianists stress "self-strengthening without rest." It must be granted that they do also say "the gentleman rests, the lesser person just drops." But that is just referring to death.

p.34

If you are not a fish, how do you know the fish are happy? Zhuangzi advocated "watching transformation" and transcending the material world rather than establishing order or gaining knowledge. This kind of tranquil contemplation is in the realm of the "aesthetic self."

p.37

Life consists of "action" and "rest." As well as striving to make a living, returning home for a break and a chat is really one of the great pleasures of life.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)