"When over 90% of mainland directors still don't know how to shoot commercial films, this is the last chance to enter the mainland market." That's the advice that Hong Kong executive producer Ng See-yuen gives to the Taiwan film industry.

The bad news is that the advice doesn't really help Taiwanese directors-since 95% of them can't shoot commercial films.

But the good news is that Taiwan currently has at least four films being shot with budgets of over NT$60 million. Could this represent a turning point? Perhaps Taiwan-made films will once again find themselves in the favor of mass audiences.

Yet if big-budget productions aren't targeting the greater Chinese-speaking market, then how can they recoup their investments? Do co-productions with mainland film companies provide a way for the Taiwan film industry to move from a narrower focus on the domestic market toward setting its sights abroad?

The Taiwan film industry performed better in 2008 than in any year during the previous decade. Apart from the tremendous success of Cape No. 7, which grossed NT$520 million and accounted for 65% of all box-office receipts for Taiwan-made films that year, Winds of September, Orz Boyz and other smaller films also did well, giving many people optimism about the future of film in Taiwan.

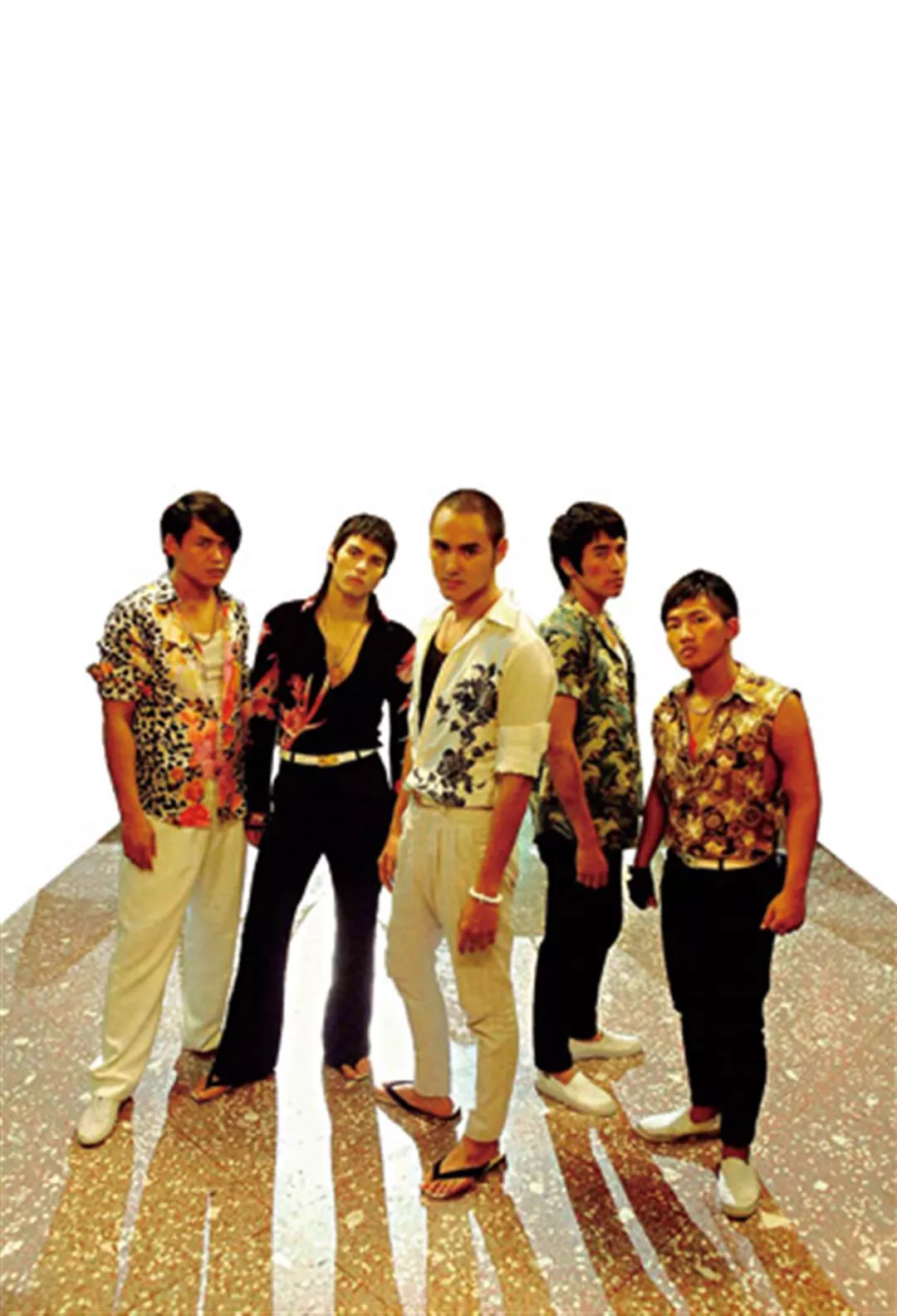

Production on Monga wrapped up at the beginning of November. The film is set in Taipei in the 1980s at a time of great ethnic strife between native Taiwanese and mainlanders who had come over with the KMT after the fall of mainland China to the communists in 1949 at the end of the Chinese civil war. It depicts the friendship of gangsters living in the Wanhua neighborhood. To increase the film's popularity, Mark Zhao, who recently won a Golden Bell award for Black & White, was cast alongside television idol Ethan Ruan. America's Warner Pictures, moreover, has given the film substantial support for distribution. Going the route more typically taken by a Western blockbuster in Taiwan, they've made 100 prints of the film for distribution here. (Typically only 40 copies are made of domestic films). Hoping to create a sensation, they plan on putting them in theaters all at once.

Television director Tsai Yueh-hsun's exquisite Black & White, whose cast was chock full of young idols, is also being turned into a film at an estimated cost of NT$150 million. And the epic blockbuster Seediq Bale that is being shot by Wei Te-sheng, the director of Cape No. 7, has attracted even more attention. The drama is something like a combination of 300, which is about a small force of Spartan warriors battling a huge army in ancient Greece, and Braveheart, which tells of the Scots defeating outside invaders. Costing about NT$500 million to shoot, Seediq Bale is a red-blooded account of Aboriginal resistance to the Japanese army.

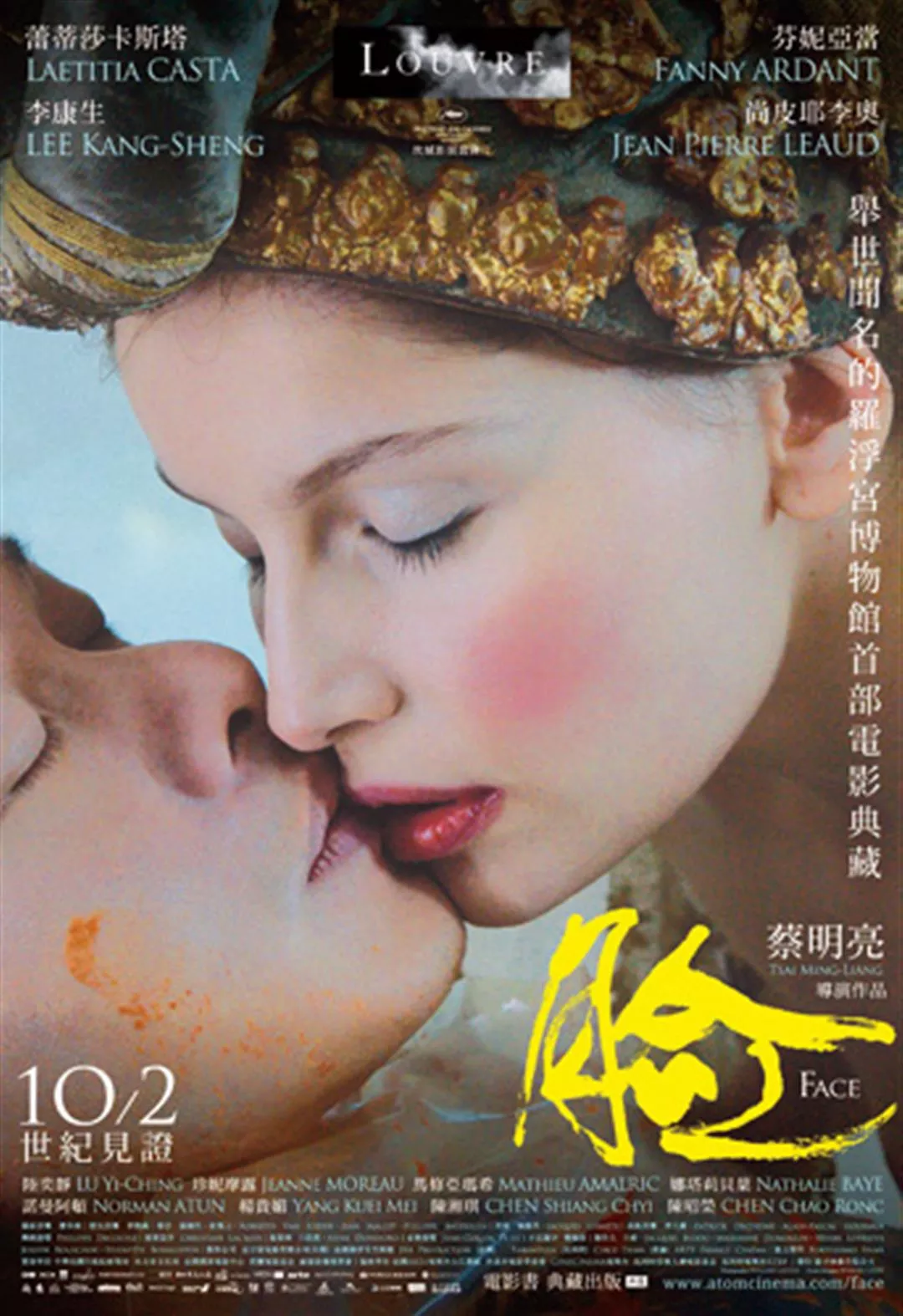

Tsai Ming-liang, a well-known Malaysian-born overseas Chinese director who is based in Taiwan, was invited by the Louvre to make a film there. He spent three years on a budget of NT$200 million to shoot Face, which describes the complicated mix of love and hate in the relationship between St. John the Baptist in da Vinci's portrait and Salome. The film is a different example of a transnational co-production involving the Taiwan film industry.

A battle for survival

Big productions can attract large audiences, but if these films are only shown in Taiwan, how can they recoup their investments?

In 2008 418 films-Chinese-language and Western-were shown in Taiwan. The total box-office take was NT$4.9 billion, which represented growth of 4.7% over 2007. Hollywood productions accounted for 70% of this sum, and Chinese-language films-comprising domestic films and co-productions-accounted for 12%. There is, moreover, a pronounced M-shaped curve experienced with Chinese-language films: Whenever big productions such as Red Cliff and The Warlords are screened, other Chinese-language films, as well as foreign art films, are squeezed out.

With ticket sales on the mainland setting one record after another, the Taiwan film industry is starting to face the music: "The future of Chinese-language film lies in mainland China." Can the Taiwan film industry turn from locally oriented productions to making films for export-aiming for the mainland and then radiating from there to Asia as a whole?

The top-grossing film made in Taiwan during 2009 was Hear Me. Three years ago well-known producer Peggy Chiao began to plan a series of films by young directors who had submitted excellent scripts. Hear Me is one of these films, and it cost NT$16 million to make. Although that's not much, raising the money was tough. It wasn't until the organizers of the Taipei Deaflympics felt that the film was a good match for the games that the last bit of financing came through in 2008. After hitting screens, the film relied on word of mouth to get going, and eventually it took in NT$25 million.

After splitting Hear Me's box-office receipts with theaters at the established rate, Chiao was lucky to come away with NT$10 million. DVD sales contributed less than NT$1 million. But she had spent NT$6 million just on publicizing the film. So although the film was the local box-office champion of the year, it still ended up making a loss. "In Taiwan the film industry and culture are both perishing. Better to exercise your right to creative expression in another market."

Chiao, who is very familiar with trends at international film festivals, says that over the last couple of years, the style of Taiwanese films has become too repetitive. There's no innovation. With new waves of films from Korea, Southeast Asia, and Latin America being discovered one after another, films from Taiwan are no longer the darlings of international film media like they were 10- some years ago. "Right now, the film industry is fighting for its life. At this time of crisis, the mainland market may be the only option remaining."

About gangsters in 1980s Taiwan, Monga has been attracting the most buzz among Taiwan-produced films released in 2009.

A convenient outlet for export?

Take 2008's Cape No. 7. Despite having a lot of cultural content that doesn't resonate on the mainland, and despite the pirated editions being sold for RMB5 on mainland streets, the film nonetheless achieved a take of RMB23 million at the box office there. That's the equivalent of more than NT$100 million. It would have been a great shame to forgo that money.

What's more, the mainland also has different regulations governing the split of revenue for foreign as opposed to domestic films-and joint productions are considered domestic films. Foreign film companies can only get 17% of profits, whereas for a joint production, the film company can earn 43%. If Taiwan film companies don't work with mainland companies to shoot films, then the films can only go to the mainland under the quota given to foreign films. How can Taiwan be successful competing for the 50 spots granted to foreign films? Going that route will only add to the difficulty of exporting.

It appears that one can't fight the trend: The mainland market simply looks too tempting. Still, many film people in Taiwan are worried about what the future holds.

"If the Taiwan film industry isn't strong enough, will it be swallowed up?" So asked Li Lieh, the executive producer of Monga, at the 2009 Chinese-Language Film Production Forum. Quite a few fledgling Hong Kong directors there expressed their envy of Taiwan's directors for the freedoms they enjoy. Distributors are calling most of the shots on Hong Kong productions, they said, so Hong Kong filmmakers enjoy less and less creative freedom.

Li admits that she once went to the mainland to try to raise money, but the investors she found all wanted to revise the script. It was going to be very hard to work with them otherwise. She and director Niu Cheng-ze struggled with the issue for a long time, but they felt strongly: "If we change the script, it will no longer be our creation." The two filmmakers are gamblers by nature, and they bet everything on its appeal to audiences in Taiwan. They hoped that by relying on their own powers to go big, they would end up with more bargaining chips with which to tackle the Chinese market if they succeeded.

Among local productions released in 2009, Hear Me has been the top box-office performer. It describes the "silent" affair of a deaf competitive swimmer. With a refreshing and unique style that stresses the power of love and communication, the film bears beautiful testimony to the spirit of youth.

A trap: cultural unfamiliarity

Kevin Chu has made money on the mainland and also been cheated there. He was one of the first Taiwanese directors to film in the mainland and to work with mainland film companies.

In 2004, he worked with Eastern Broadcasting Company to shoot the television movie Two Birds with One Stone. The mainland company bought the rights to it for RMB1 million. After it was turned into prints, it was shown at 300 theaters there. When Chu went to the theater, he almost fainted. Dusty and dark when projected on screen, the quality was horrible. Rather than Dolby, the audio sounded like it was coming from a transistor radio. Nevertheless, even under those circumstances, the film was able to gross RMB20 million.

Back then, the Taiwan film industry had hit hard times. Those economic circumstances, combined with cordial invitations from mainland film companies, lured him into executive producing on joint productions. In 2005 he hired the Lin Helong, a director of teen idol films, to shoot Wolf, which was filmed at a cost of about RMB1.8 million. Under the deal he signed, his mainland partner first issued a RMB100,000 deposit. But when they had finished filming, his partner refused to pay the rest of what he owed: "Right now the film industry is experiencing tough times," he said. "There's no money."

Chu considered his options: Under the circumstances, why shouldn't the two cancel their agreement, so that Chu could look to sell the work to someone else. But the other side wasn't amenable. Fearing the trouble that might ensue, Chu eventually accepted selling the film to his original mainland partner at a discount of 50%. It was only later that he learned that the other party was only a low-ranking manager for a film studio in Zhejiang. He was just speculating.

Even with that setback, Chu had already caught a glimpse of the tremendous potential in the mainland market.

The white sneakers, flip-flops, and flowery shirts worn by the cast of Monga, including leads Ethan Ruan (center) and rising-star Mark Zhao (left), create a look that is eye-catchingly gauche.

The blockbuster strategy

In 2007 Taiwan's Government Information Office (GIO) promoted its "strategic film" plan, increasing the amount of assistance given to medium-sized and major film productions (about two to three films a year). Films with a budget of at least NT$30 million can receive a subsidy as high as 30%. In 2009 the definition of a large-budget film was raised to NT$80 million, and the government is encouraging the film industry to form joint productions with film companies in Hong Kong, China and other Asian nations so as to spread the investment risk.

Kung Fu Dunk, which cost US$10 million to make, received a NT$15 million grant from the GIO. With financial backing from Taiwan's Chang Hong Channel Film and Video, and Hong Kong's Emperor Entertainment Group, the film took a rather ordinary story of a man using his basketball skills to help him find his family, and then added some exaggerated slapstick humor, some special effects and an appealing lead: the superstar singer Jay Chou. The film ended up coming away with NT$30 million at the Taiwan box office. That wasn't enough to break even, but the film also earned RMB200 million on the mainland, and US$4.3 million (about NT$140 million) from selling rights to other foreign markets, such as Japan, Korea and Hong Kong.

In 2009 Kevin Chu once again used Jay Chou and paired him with Taiwan beauty Lin Chiling to shoot The Treasure Hunter, which was about a couple that was deeply in love but frequently butted heads. The exterior shoots were filmed in the desert at Yingchun in Ningxia Province. With tornados, dust storms, oases and other unusual images, the cost of filming rose to NT$400 million. It is hitting the screens in China at the end of December 2009, and will be up against some other big productions, including Bodyguards and Assassins, on which Peter Chan was executive producer, and Zhang Yimou's Amazing Tales: Three Guns. It will be a full-on confrontation between works produced in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Monga's director Niu Cheng-ze (center), who came to directing after being a child actor, made a cameo appearance in the film. It helped soothe Niu's itch to act again.

Big financing, big trouble

Kevin Chu, who specializes in comedies, is Taiwan's most representative director of commercial films. It's easy for him to raise money. But how should other directors, who might have a strong art-film sensibility or who might be unfamiliar with the dramatic pacing of commercial films, take the first step in raising funds?

Director Wei Te-sheng's second dramatic film Seediq Bale is costing NT$500 million to shoot. Although it has received a subsidy from the Government Information Office of NT$160 million because of the outstanding box-office performance of Cape No. 7, and although it has also received some private financing from investors in Taiwan and Hong Kong, it still has a budget deficit of NT$200 million that makes Wei very nervous.

Calculating carefully, he determined that even if he achieves another box-office "miracle" in Taiwan with receipts of NT$500 million, because of the 60-40 cut favoring theaters, he will reap only NT$200 million. After subtracting actors' cuts and production costs, the film could still lose money. Because the production costs are so high, Seediq Bale has required a cross-strait joint production. The response that the mainland audiences will have to Aboriginal Taiwanese fighting the Japanese remains to be seen.

On the other hand, Black & White, which was adapted from a television show that was a hit with critics and audiences alike, has money in the pipeline. Double Edge Entertainment, which is handling the executive producer role, announced in September that it had successfully drawn up a co-production agreement with the mainland's China Film Group. CFG even agreed to put up 60% of the money, but a precondition was that the script had to pass their inspection.

Says Double Edge's head of production, Wolf Chen: "You won't understand all the 'ins and outs' unless you talk to them." For example, this drama of good versus evil features a criminal gang known as "Heaven's Group." But for the film version, the production company thought that the only truly "evil groups" left in the world were in North Korea, so they considered giving the gang a North Korean background. But as soon as their mainland partners heard that idea, they were vigorously opposed because North Korea is an ally of mainland China and could not be criticized. Then, in order to strengthen the plot's connection to China, Double Edge thought it would be better to add a character from the mainland police to come and help crack the case, but its mainland partner nixed that idea, because were such a figure to appear, the film would have to first be sent to the Ministry of Public Security before going to the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television. It would add a lot of potential hassles.

Shooting for Seediq Bale, the second film by Cape No. 7's director Wei Te-sheng, began on the 79th anniversary of the Wushe Incident, which is depicted in the film. The production crew and members of the Seediq Aboriginal tribe together pray that all goes smoothly on the production.

Victory goes to the creative

In order to grab a share of the market, Taiwanese directors need to practice their skills at controlling a big-budget production. But many observers don't recommend that Taiwanese directors immediately shoot large-scale productions because of the risk involved.

From investors' standpoint, finding more investors to spread the risk would be worthwhile. The problem is: what kind of film do you have to shoot to make money in the mainland? What exactly does Taiwan have to sell?

After The Warlords, many predicted that people would tire of big-production period-costume films. But Hong Kong director Peter Chan rejects this view, saying, "Chinese culture and history are the common assets of mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The costumes refer to the era; they don't define the film type. Costume productions can be ghost films, romances, thrillers, detective stories, and so forth. There are at least 18 different kinds of film that you can do in costume."

Having shot films in China for five years, Chan understands that "Big productions aren't just favored on mainland China; audiences all around the world love to watch them. Nowadays watching films has become a kind of spectacle. Art films you watch on DVD, but blockbusters full of special effects you watch in cinemas."

But some film people see things differently. "There has been a trend toward shooting big budget, big-cast productions," acknowledges Peggy Chiao, who founded the Graduate Institute of Filmmaking at Taipei National University of the Arts. "But having such large sums of investment money available may end up limiting the kinds of material chosen, so that the types of film being shot become narrower and narrower." Chiao recalls that a few years ago various European film people, especially the French, were howling in protest about the "bourgeois" and "vulgar" blockbusters coming from Hollywood. Films should not put so much emphasis on production values that they destroy all room for small and medium-budget films, which have value as cultural representations.

Although historical films with casts of thousands and action-packed kung-fu flicks are popular in China, urban comedies directed by Feng Xiaogang also do well at the box office there. Yet because of cultural and linguistic differences, they are rarely successful in Taiwan.

"Taiwan filmmakers often confuse 'creativity' with 'innovation," says Wolf Chen, Double Edge's head of production. Chen contends that creativity involves standing on someone else's shoulders and then developing farther. For instance, Hollywood likes to buy the rights to best-selling classic novels and then update them to be extremely current-because the governing logic of commercial films is: "You've got to get people to shell out to go to a movie theater."

Among local productions released in 2009, Hear Me has been the top box-office performer. It describes the "silent" affair of a deaf competitive swimmer. With a refreshing and unique style that stresses the power of love and communication, the film bears beautiful testimony to the spirit of youth.

A marathon

No matter what Taiwan filmmakers shoot, the guiding principle should be: Don't mess with your own approach just because you want to do a joint production with a mainland film company.

"Joint productions with mainland companies just represent a new option!" says Yeh Jufeng of Ocean Deep Films. Whether producing a film entirely in Taiwan, or working on a co-production with mainland Chinese, Europeans or Americans, each of these options just represents one choice. The scale of the film depends on how much money you raise; but the depth and feel of the work should remain the most important thing.

Yeh, who has been an executive producer for many new directors in Taiwan, says we shouldn't criticize new directors for always describing their own youth. New directors have to shoot their first films on GIO grants of just a few million NT dollars. "Could they shoot a ghost film on that?"

Although she appreciates creative talent, she nonetheless feels that many Taiwanese directors seem too willing to stay in Taiwan and shoot music videos, commercials, shorts and corporate introductions, vainly enjoying the prestige that comes from saying they are directors. They aren't willing to condescend to be an assistant director and go participate in and learn about making a big picture. That kind of attitude and approach has got to be changed.

Yeh spent eight months with director John Woo shooting Red Cliff. She was the lone representative of Taiwan in the production crew of 800. She was responsible every day for the money for food and drink, and for the schedules of 120 vehicles and 120 drivers.

The preliminary preparations for Red Cliff and the size of the production opened up a new world for Yeh. For instance, the crew built Cao Cao's castle on a field outside of Beijing that they rented for three years. In the first year, they used earth to cover the field, making it gradually level. In the second year, they built the sets, and in the third year they returned it to its original appearance. There couldn't be any delays.

Beijing Mandarin, Shanghainese and Cantonese were all used at work. But a certain amount of cultural and linguistic barriers engendered feelings of loneliness. Yeh wanted to bring some people from Taiwan over with her, but, she noted, "If you bring your own people over, they've got to be up to it. They can't be lethargic or indecisive. They've got to be diligent and able to suffer hardships. And you've got to be able to withstand some sarcasm occasionally directed your way. Sometimes you just have to grin and bear it because you're a guest in someone else's land." Thinking it over, she decided just to go by herself.

Cross-strait co-productions have opened up a new sales door for Taiwanese films, but it's still a big question as to what kinds of films will be produced as a result. Whether in terms of talent, financing, creativity or marketing, one thing is for sure: making a film isn't a sprint but a marathon. Those working in Taiwan's film industry need to ask: Are we ready?

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)