Lin Ching-lan: Dancing to Her Own Beat

Liu Yingfeng / photos The Lin Jing Lan Dancers / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

May 2016

Dancer Lin Ching-lan, 29, who was born with a severe hearing impairment, lives life dancing to her own beat.

She performed at the Taipei Deaflympics in 2009 and was crowned Miss Deaf Asia at the Miss–Mister Deaf Asia pageant in 2015. Early this year, Lin, pretty and fine-featured, signed with SK-II skin care products, joining luminaries such as actress Tang Wei from mainland China.

To outsiders hers is an illuminating and inspirational story, but in Lin’s own eyes it’s quite a bit simpler than that: It’s all about hard work and the determination to remove the labels that society puts on deaf people. She wants to show that what other people can do, she can do too.

Lin’s dance studio is an unremarkable apartment in Sanchong belonging to her grandmother, which Lin has renovated. There she ties her hair back into a ponytail and starts a regular Tuesday rehearsal with a group of six or seven other deaf people. When she turns on the music, she gathers her focus, not to listen to the melody, but to carefully feel for the rhythm that the sound waves transmit via the floor. Through the soundproof glass door, an onlooker without previous knowledge would never guess that Lin was someone who had been deaf from a young age.

Feeling rhythms from the floor is a dancing skill that Lin discovered while competing in a dance contest when she was a college junior.

As the competition neared, Lin increased the time she spent practicing. Yet, despite her best efforts, she couldn’t keep up with the beat. She found it all very depressing. Her mother consoled her: Dancing should be about having fun, not competing. With that change of perspective, Lin felt much more relaxed when she went to the performance venue and prepared to rehearse. The sound system that was set up transmitted a strong beat, shaking the floor ever so slightly. She danced with it, surprising herself by keeping the beat throughout the performance.

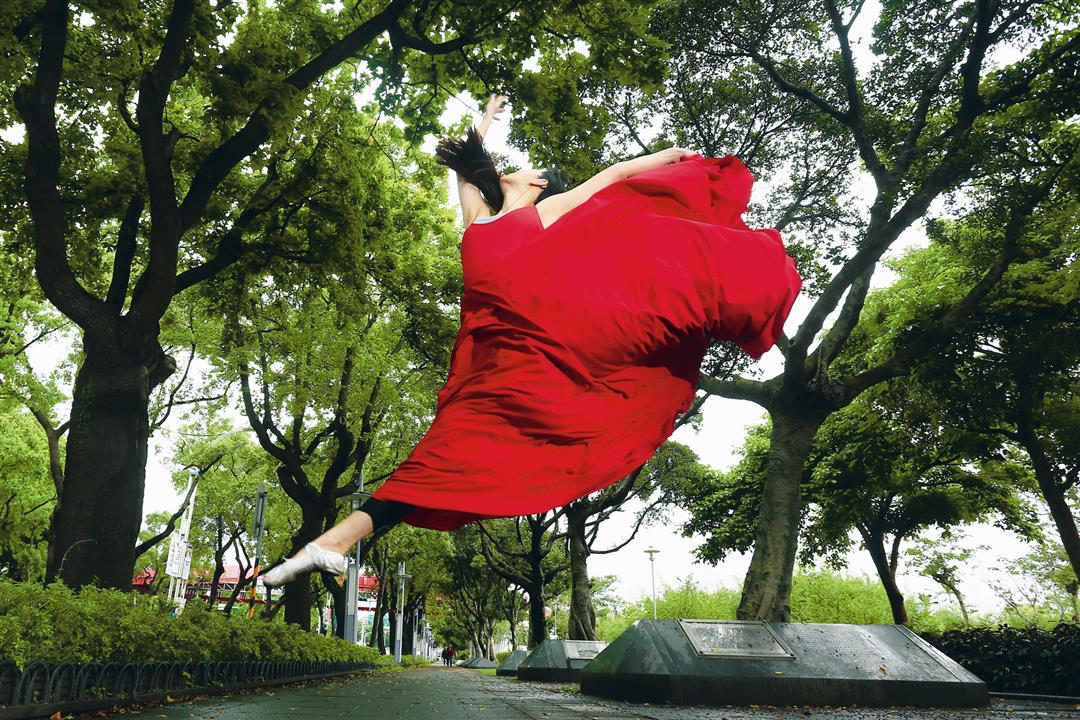

Her eyes focused as she feels with her feet for the beat, Lin is able to stay in rhythm. Just by looking at her dance, no one would ever guess that she was hearing impaired. (photo by Jimmy Lin)

“Listening” with her feet

Lin has been dancing for a long time, but it wasn’t interest that initially sparked her participation. Rather, it was a means of improving her health. Her kindergarten teacher recommended she start dancing to get into better shape, and once she started, she kept at it for over a decade.

Looking back, Lin thinks she was a pretty clueless dancer when young. It wasn’t until she was in college and was invited to choreograph a dance by an older student that she began to feel a sense of accomplishment and true passion for dance. Although it was only a short piece, the creative experience was deeply rewarding.

Long Chia, who has worked with Lin for four or five years, knows for sure that it hasn’t been easy for Lin. Lin’s hearing impairment is severe. “Whereas other people can listen to music and practice dance, I have to use my eyes to capture the beat and learn the moves,” Lin says. A dance that others can learn in a week might take three or four times as long for a hearing-impaired person. And in addition to the hardships she endures today, Lin also holds unhappy memories from studying dance as a child.

She experienced a lot of hurtful unfriendliness back then—perhaps, she thinks, because people didn’t understand the hearing impaired, and didn’t know how to interact with them. At any rate, the experience made her want to make a contribution on behalf of all deaf people. In 2011 she founded her own dance company, hoping to provide a relaxed and happy dancing environment for the deaf.

Many of the other members of the company are likewise deaf. Some of them initially lacked confidence, but as they gained opportunities to perform, their faces brightened and they took to moving more energetically on stage. Long Chia notes that one shy member of the group, Huang Xiaobu, at first just helped out by taking photos for the group. But then, with the encouragement of her mother and others, she joined the company and started to dance herself.

In addition to establishing a deaf dance company, Lin has even gone so far as to head south to Taichung week after week to teach dance to deaf children. One class went on for four months, and then in the last session Lin discovered that a student that had regularly come to every class was missing. It was only after she asked why that she learned that the students’ parents couldn’t afford the tuition. Lin thus learned that the families of many deaf people may find even reasonable fees a heavy economic burden.

According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan currently has 120,000 hearing-impaired people, comprising roughly 10% of the nation’s disabled population. Cochlear implants cost tens of thousands of NT dollars, and the parents of many hearing-impaired children are deaf themselves. “Making ends meet for basic necessities is tough enough—never mind having the financial wherewithal to pay for their children’s dance lessons.” Consequently, Lin has kick-started the “Crescent Moon Plan.” Phase I involves Lin and her partners going on tour to raise funds to support dance education for the deaf.

(photo by Jimmy Lin)

Competitive and eager to make a mark

“Is dancing hard work?” Carefully reading the lips of those who ask this question, Lin always answers no.

The eldest of the children in her family, Lin was always stubborn and competitive growing up. She often argued with her parents about whether she should wear a hearing aid. When she grew older, her mother expressed the wish that she start working right after high school. But Lin was firmly opposed to the idea, and enrolled in National Taitung University, far from home.

When Lin speaks, she enunciates every word very clearly. Chia, who is responsible for arranging the company’s performance schedule, notes that it’s not easy for the deaf even to learn just basic pronunciation, but Lin has gone far beyond that, expending much time and energy to study lip reading, diction and articulation. During practices, Lin will want the dancers to practice over and over even a simple flag-waving motion, until they get it precisely. Lin’s mother, who studied dance for many years, recalls, “One time I tried copying the way that they were moving their arms, and I found it exhausting.”

Lin makes such demands of herself because she wants people to stop putting negative labels on deaf people. She hopes to prove that she and the members of her company are on stage because of their expertise, not because of the sympathy they evoke. Chia once asked her: If she had her life to do again and was given the choice of whether or not to be deaf, how would she decide? Without hesitating, Lin chose deafness: “If I’d had normal hearing, I wouldn’t have worked so hard!”

(photo by Jimmy Lin)

(photo by Jimmy Lin)

Last year Lin launched the Crescent Moon Plan, which provides deaf children with the financial means to experience the joys of studying dance. Below, Lin teaches a class of hearing-impaired children.

in was crowned Miss Deaf Asia at the Miss–Mister Deaf Asia pageant in 2015. The award has brought her international attention.

Lin and the members of her dance company have traveled to France, India, and Singapore, where they performed with great confidence and panache.

Lin and the members of her dance company have traveled to France, India, and Singapore, where they performed with great confidence and panache.

Fearless in the face of obstacles, Lin keeps moving as a means of self-affirmation, feeling the beautiful beat of life.

Showing true grit, Lin Ching-lan is determined to tear off the labels that society places on deaf people. She wants to prove that if other people can do something, so can she. (photo by Jimmy Lin)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)