“I Don’t Tell Stories. I Don’t Entertain.”—The Films of Tsai Ming-liang

Su Hui-chao / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

September 2014

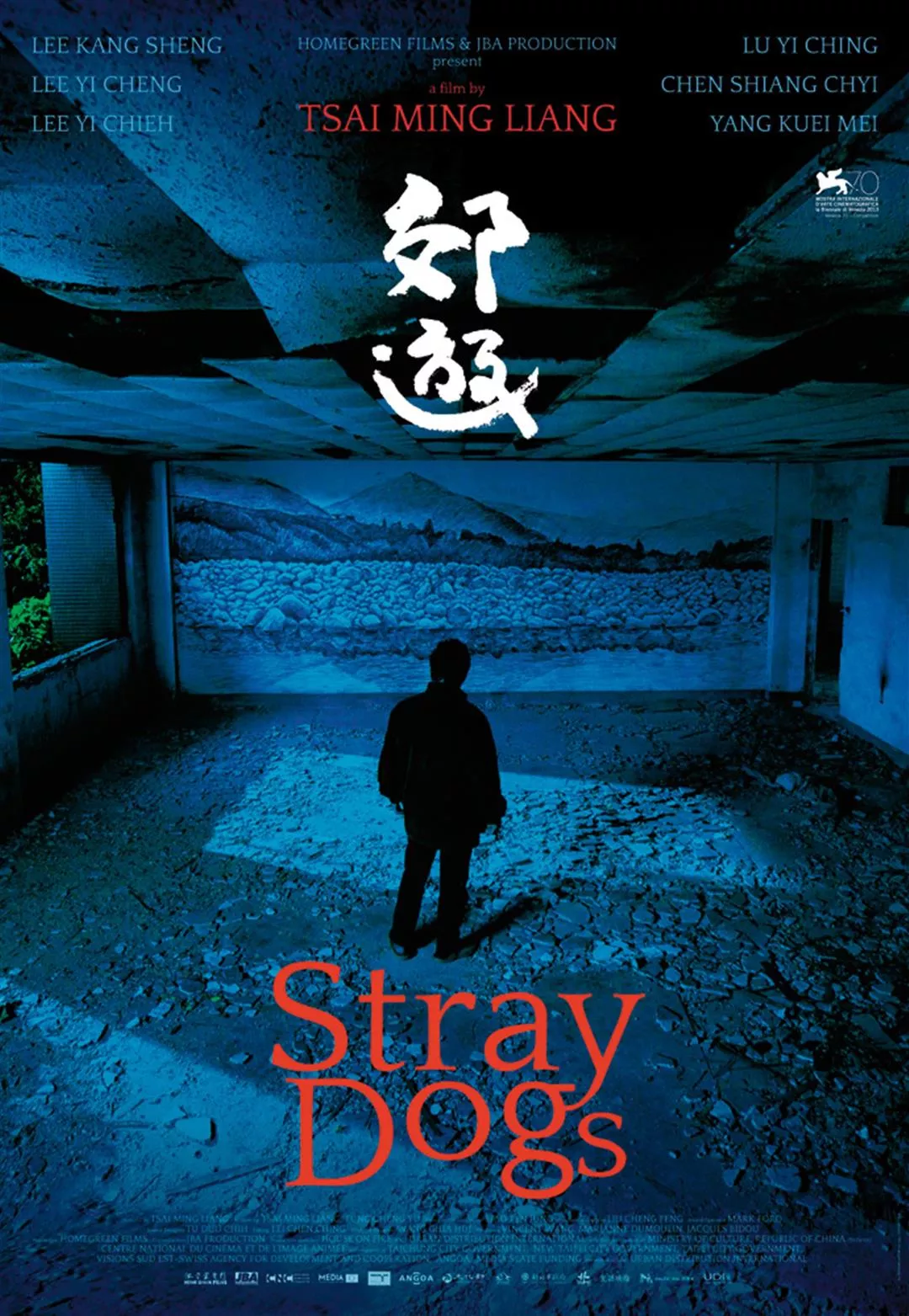

After Stray Dogs picked up the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival and then garnered Golden Horses for best director and best actor back in Taiwan, director Tsai Ming-liang declared that it might be his last film. “I’m fed up with working so hard, and with certain values embraced by this world,” he said.

In July Tsai published a director’s notebook on Stray Dogs. In the book he delves into his own thoughts about making films that neither tell stories nor entertain. And in an interview with Taiwan Panorama he discussed his past, present and potential future.

It was probably more than a decade ago that Tsai Ming-liang first saw a person employed to hold an advertising placard.

The sign was touting some kind of travel product rather than the usual real estate. As cars and pedestrians passed on the busy street, the holder became seemingly as invisible as air, the sign replacing his face and body.

The scene shocked Tsai and filled him with sadness. Had it really come to this, where work becomes a form of standing punishment? Resembling children in “time outs,” these workers were losing their dignity for less than NT$100 an hour.

What he saw he remembered, and a series of question marks lodged in his mind. More than a decade later, in Tsai’s 11th film Stray Dogs, the character played by Lee Kang-sheng becomes a holder of signs advertising real estate. His marriage falls apart, he loses his job, and he has two children living away from home. In one short scene in the film, the character pours out all his indignation and frustration by belting out “Red, Red River.” That scene alone, without even the need for watching the earlier scenes that put it in context, is earthshaking in its power. It’s so heartrending it’s painful.

Of course, Stray Dogs is not simply “the story of an unemployed man.” “A story” or even a screenplay is never at the heart of a Tsai Ming-liang film—and “entertainment” even less so. The familiar conventions of filmmaking, the physically attractive leads, the moving music and complete story arcs are all downplayed, indistinct or even completely non-existent in Tsai’s films.

Tsai’s play The Monk from Tang Dynasty gives speed-obsessed modern people a taste of the “slow” spirit embodied by the Tang-Dynasty monk Xuanzang.

Tsai’s first film, Rebels of the Neon God (1993), which did have a story, was at the vanguard of experimental neo-realism in Taiwanese film and depicted the loneliness and melancholy of youths at the margins of Taipei society. In Vive l’Amour, which came out the following year, Tsai boldly used just three actors without even 100 lines among them. He made frequent use of a telephoto lens for close-ups, and the film lacked a musical soundtrack or any true narrative arc. It is pervaded by a vast sense of loneliness in the world as time slowly turns. Audiences came away puzzled. “Tsai Ming-liang’s style” was born.

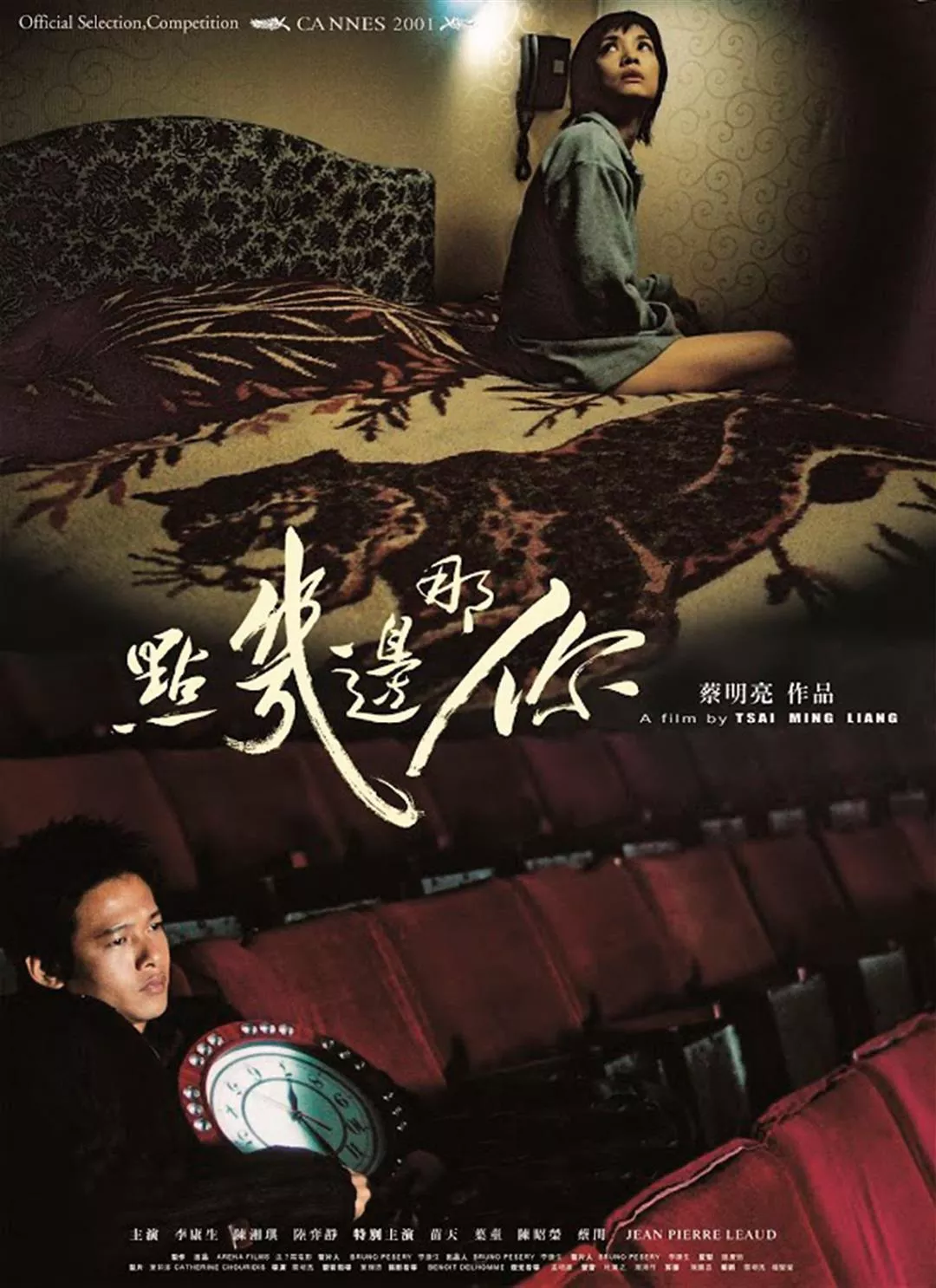

Vive l’Amour won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Then The River, The Hole, What Time Is It There, The Wayward Cloud and Goodbye, Dragon Inn went on to earn Tsai awards at a variety of international festivals. With a high-profile international reputation established, he didn’t need to go looking for money to fund his films. The money found him.

Some people say that if you can stand a film where the actors say nothing for the first 20 minutes, if you can stand an ending where the female lead cries in front of a mirror for six straight minutes, if you can stand shots of a theater with 1000 empty seats where nothing happens, where the only seat filled with a person is then vacated too, where the camera remains completely fixed before quickly revolving around the same exact scene—if you can handle all that, they say—then you have what it takes to appreciate Tsai Ming-liang’s films.

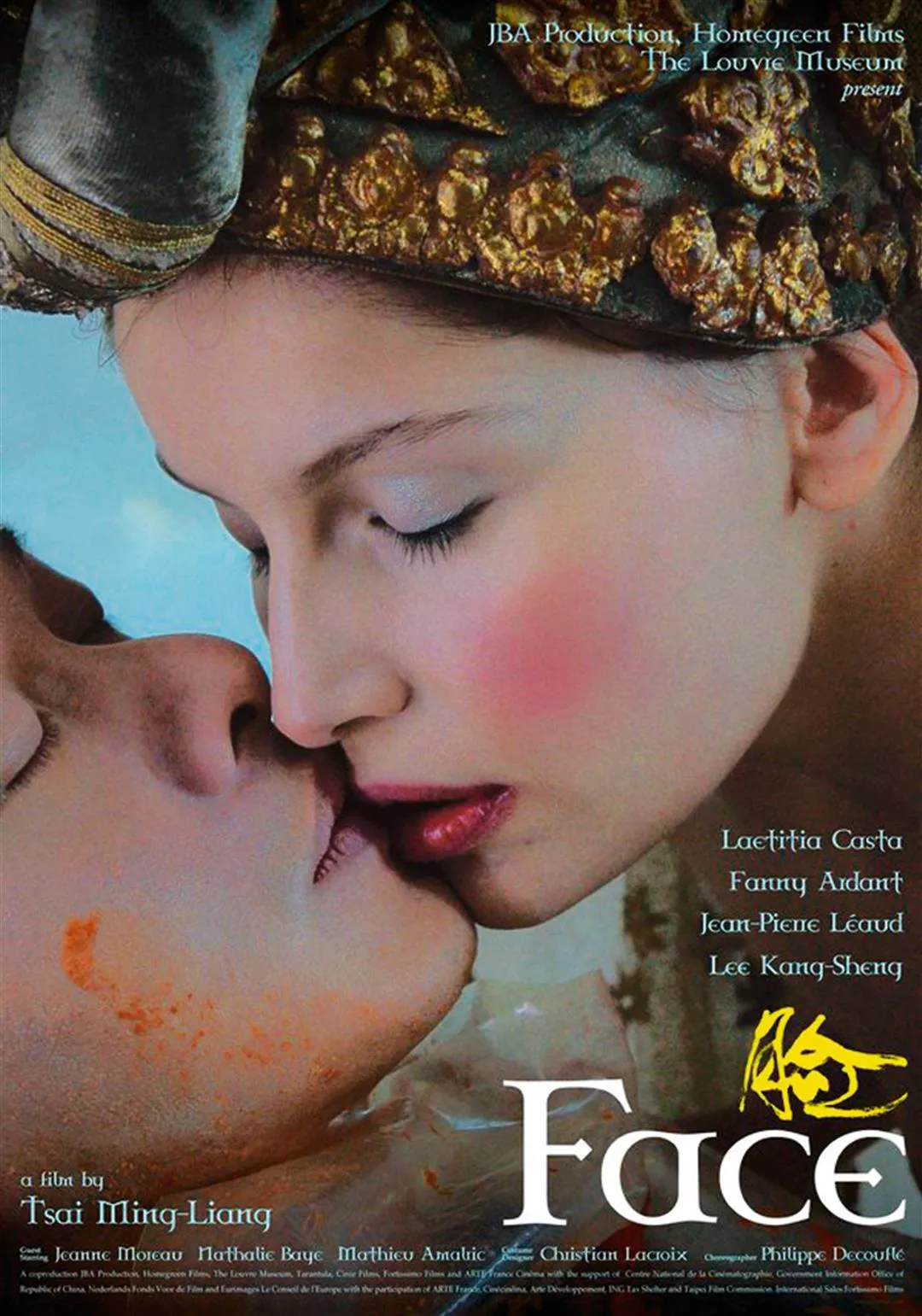

In 2009 Face frustrated audiences even more, driving some to storm out in disgust. The film was shot on commission for the Louvre, which was attracted by Tsai’s conception of filmmaking and overall creative style. Consequently, Tsai determined that his future would be in filming for the collections of fine art museums.

Films of this type, especially by Tsai, require cultural and psychological preparation. Consequently, Tsai accepted the invitation of Chu Anming, head of Ink Publishing, to write a director’s notebook about Stray Dogs, taking the opportunity to answer the public’s questions: “Everyone wants to ask, what is this director—who isn’t popular, and whose films are incomprehensible box-office flops—doing?”

Taking death as its starting point, Tsai’s What Time Is It There? explores the loneliness and alienation of the human condition. An old watch prompts the film to shift its focus back and forth between Taipei and Paris.

Whether shooting films or not, Tsai is a sensitive and unique individual, a true artist.

He was born in Malaysia and still holds a Malaysian passport. His father, who had a noodle stand, was taciturn and severe. But starting at age three, Tsai went to live with his maternal grandparents. The two old persons would take turns bringing him to watch movies. When his father brought him back home because of poor marks at school, Tsai would sit under a mosquito net and dream up stories, imagining that he and his grandfather had escaped deep into the mountains. He wove all manner of detail into those fantasies. Sometimes he’d find them so moving that he’d come to tears.

During high school Tsai began to write essays and submit them for publication. He organized a drama club and wrote radio plays. When he was 20, a passionate youth from the tropics, he came to Taiwan, where he enrolled in the drama department of Chinese Culture University. He watched a lot of films, and Wang Shaudi introduced him to the concept of “living theater.”

In his sophomore year he saw François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows. In it the youth Antoine is arrested for stealing his father’s typewriter. He shares a paddy wagon with a bunch of prostitutes on his way to reform school, as Paris recedes into the distance. As Antoine grips the metal bars of the window, tears roll down his cheeks. At that moment Tsai suddenly understood that people are always engaged in a conversation with their environment and their city. What we hate to abandon is a city or a way of life, not a particular person. Consequently, he understood the “power of cinema,” and understood why shooting films had value beyond reasons of money and vanity: it unfolds before viewers as an artistic medium that provides a mirror of one’s own life path.

Tsai has never shown fear of being an outcast or taking a different path in life. When he was 25 a drama company he had founded put on the 40-minute play A Sealed Door in the Dark. It completely lacked dialogue and was one of Taiwan’s first dramatic works to deal with issues of male homosexuality.

With a style that runs completely counter to the conventions of commercial films, Tsai makes films with an artist’s perspective. It wasn’t until 2013 that his work was recognized with a Golden Horse for best director.

Fate would have it that he would meet Lee Kang-sheng in a gaming arcade. Lee was a youth who didn’t feel like taking the joint entrance exam for university. Beginning with The Boys (1991), a stand-alone drama for television, he would become an integral part of Tsai’s work and featured in his films from Rebels of a Neon God to Stray Dogs, as well as Tsai’s stage plays Only You and The Monk from Tang Dynasty. The most captivating chapter in the director’s notebook on Stray Dogs involves a discussion between Tsai and Lee.

“That face of his—other people didn’t see it but I did. For more than 20 years it’s like I’ve been nurturing some rare and fragile variety of plant, watching it grow from a tender seedling to a stout tree. He’s become irreplaceable. It’s quite extraordinary.” To Tsai, Lee’s face is tangled up in his own memories of his grandfather and his father, and it also bears tracks etched by the slow movement of time. With this face as a launching pad, Tsai’s films have always aspired to break the mold, abandoning all knowledge of film and the things filmmakers have been so dutifully taught. Yet, in that case, what does Tsai shoot?

Stray Dogs uses an extremely simple narrative structure to describe the struggles of an unemployed father. The film shocked audiences and won one award after another at international film festivals.

As far as Tsai is concerned, there are only two important components of a film: the composition of images and the passage of time. The first is really what film is all about, what the art of filmmaking is. Apart from these two components, everything else can be cast aside.

Tsai’s films tend to show what he sees in life through realistic scenes with tight compositions. Life is conveyed by sequences or non-sequences of film segments that depict eating, sleeping, spacing out, defecating, urinating… any action or behavior that Tsai sees. Life is a story that is pieced together. More often than not, it is unintentionally fragmented and involves only a slow process of comprehension. Tsai sees that. The anxiety, the darkness, the cruelty, the desolation—he sees all that too. If life is full of anxiety, his films show anxiety. If the truth is cruel, his films show cruelty.

“So what I’m doing is really very simple: What I see and experience I hope you see. But I can’t force you to know something or to understand. You’ve got to do the knowing and understanding for yourself.”

If someone understands what time is and can quietly appreciate watching the moon in the sky, then Tsai believes such a person can appreciate his films. Appreciate, not understand, like appreciating a painting.

Tsai Ming-liang and Lee Kang-sheng are masters of their professions and good friends. At the 50th Golden Horse Awards they respectively took home the best director and best actor awards for their work on Stray Dogs.

If Stray Dogs really is Tsai’s last film, then The Monk from the Tang Dynasty, a play being performed at the Guangfu Auditorium in Zhongshan Hall, may be the last chance for audiences to approach Tsai.

Tsai has long admired the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang. In Tsai’s estimation, Xuanzang’s exploits were amazing but also subversive, a form of rebellion against the world. He cultivated virtue by walking alone through the desert to India to gather Buddhist scriptures, converting bandits who tried to kill him along the way.

In 2011 the National Performing Arts Center sought out Tsai to hold some one-man shows. He selected three actors with whom he had long working relationships, including, of course, Lee Kang-sheng. Tsai gave him a scenario and told him to act himself, Tsai’s father and Xuanzang. That play is Only You. When Lee spent 17 minutes to cross half the stage as the sole figure on it, the tension that he was able to create so moved Tsai that tears filled his eyes: “For 20 years, I’ve waited for you and this moment.”

Tsai watched Lee walk, slowly, confident and unhurried. That youth he had long worked with had transformed into the monk Xuanzang. The actor moved with Xuanzang’s spirit, slowly and in total resistance to this fast-paced age.

Only You sparked Tsai Ming-liang’s three-year “slow long march” series. Lee Kang-sheng transformed into Xuanzang, wearing saffron robes at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels and the Vienna Festival, before returning to Taiwan for the 2014 Taipei Art Festival. Next year he is going to go to Gwangju, South Korea.

When Tsai asked Lee what he was thinking about when walking, Lee said, “I recite the Heart Sutra.”

Tsai first read the Heart Sutra a long time ago. Recently he has often recited or copied out the Diamond Sutra. When facing illness or facing death, or when boarding an airplane, people often recite sutras to calm themselves. That was the original attraction for Tsai. “The sutras have a karmic pull.” But gradually they came to bring him joy, and eventually he came to a greater understanding of them. He no longer recites them for comfort. “There’s nothing to seek, because everything is illusory. The Buddha even tells us that he isn’t saying anything.”

That’s similar to Tsai’s films: they say everything and they say nothing. They raise no questions and provide no answers. They are flowers reflected in a mirror or the moon’s image on a lake, nothing more nor less than projections of the mind. When Tsai takes this point of view, he fills with a sense of contentment. Malaysia nourished his childhood. Taiwan gave him creative freedom. His films aren’t big money makers, but he has had films to shoot for more than 20 years and has been able to collaborate with like-minded people. He has delved into the core issues of our age. He is also a collector of old things, and has even opened Director Tsai’s Café Galerie. It is if he were living at the edges of a ruined city.

He wants to tell people that if he really doesn’t shoot any more films, please don’t say he has given up the battle and pity him, because he is happily passing his days the way he wants to. If one day he does shoot another film, even a commercial film, please don’t feel that he has degraded himself. Such a move on his part would simply mean that he felt like playing with something new.

“Everything that has marks is deceptive and false. If all marks are not seen as marks, then this is perceiving the Tathāgata.” That is the realm that Tsai is headed toward.

After the Louvre commissioned Tsai to shoot Face, he decided to focus on films for the collections of art museums.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)