Pictures and statues of divinities supply an inexhaustible wealth of material in discussing Chinese forms.

Despite variations over time and place, the forms of the various gods and goddesses--their features, expressions, postures, apparel, and the objects they hold--generally adhere to certain rules. That is because each god and goddess possesses special attributes or duties which must be represented symbolically in the form in which he or she is portrayed.

The Buddha, for example, is invariably shown wearing filthy rags, in contrast to the beautiful garments and precious jewelry worn by bodhisattvas, to signify how he cast away worldly pleasures when he entered the ascetic life.

Ma Tsu has the expression of a kind and loving mother, reflecting her congeniality and attractiveness to believers. while statues of Ming Wang are generally fearsome in visage, to express his power to drive away evil.

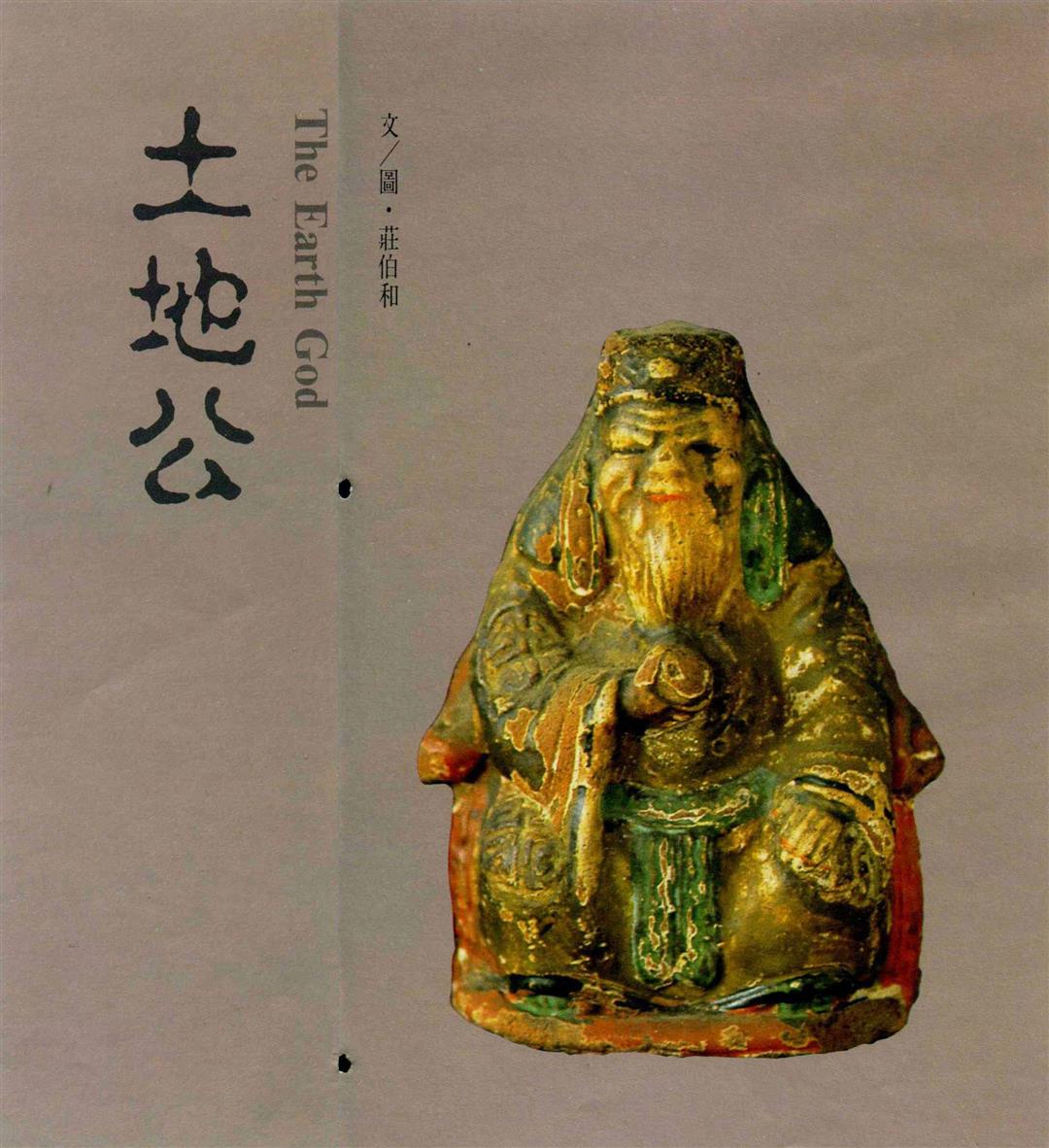

Typical in form also is the image of t'uti-kung, the god of the earth, which is recognizable at a glance to most people on Taiwan, where his worship is particularly widespread.

Man's belief in the divinity of the earth dates back to far antiquity, to the worship of the earth goddess, who was held to propagate life and nourish agriculture. As to exactly when the belief in a male earth god arose, a definitive answer must await further study.

Judged, however, from chapter five of the Sou-shen chi, or In Search of the Supernatural, where Chiang Tzu-wen styles himself the god of the earth, the belief in an earth god existed as early as the first half of the third century. The belief grew in popularity during the fifth century and by the seventh had spread over the whole of China.

Shrines to the god were built in each area of the country, and his name is recorded in a fifth-century Taoist scripture that has been unearthed from the caves at Tunhuang. The belief later entered deeply into the popular consciousness. In the sixteenth-century novel Hsi-yu chi, or Journey to the West, for example, Sun Wu-k'ung, or Monkey, always asks the local earth god to appear and report on what's happening whenever he arrives in a strange place.

As to the prototype of the god himself, opinions differ. Some say he is a deification of Hou Chi, the official in charge of agriculture under the ancient emperor Yao. Others say he originated in Chang Fu-teh, a benevolent tax official of the Chou dynasty who sympathized with the people's hardships and was later honored as a god.

In fact, the earth god is rather low in status. His shrines are small affairs compared with the temples erected to other deities, and if he appears in a larger temple at all it is only in a secondary, supporting role.

But just because of his humble status, the earth god is closer and more accessible to the people. "At each end of the field is a t'uti-kung," the proverb says, indicating the vast number of his shrines that dot thecountryside. Families engaged in business worshipped him on the second and sixteenth of each lunar month, and the second day of the second month is his birthday.

A deep part of popular belief, the earth god is turned to for help in all sorts of circumstances. Securing wealth, a rich harvest, or a prosperous business hardly needs mentioning; he is also asked to help out in curing a disease, gaining a promotion, or changing one's occupation.

As to his form, the earth god is generally pictured as a white-haired, kindly old man, rich in experience, generous with his wealth, and happy to help others in whatever they ask for. He is sometimes shown holding bars of gold and wearing clothes embroidered with the character for longevity.

His wife, who is said to be stingy and to resent his giving away their wealth so freely, is out of favor with the public and is rarely pictured with him in shrines and temples--yet another curious aspect of folk belief.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)