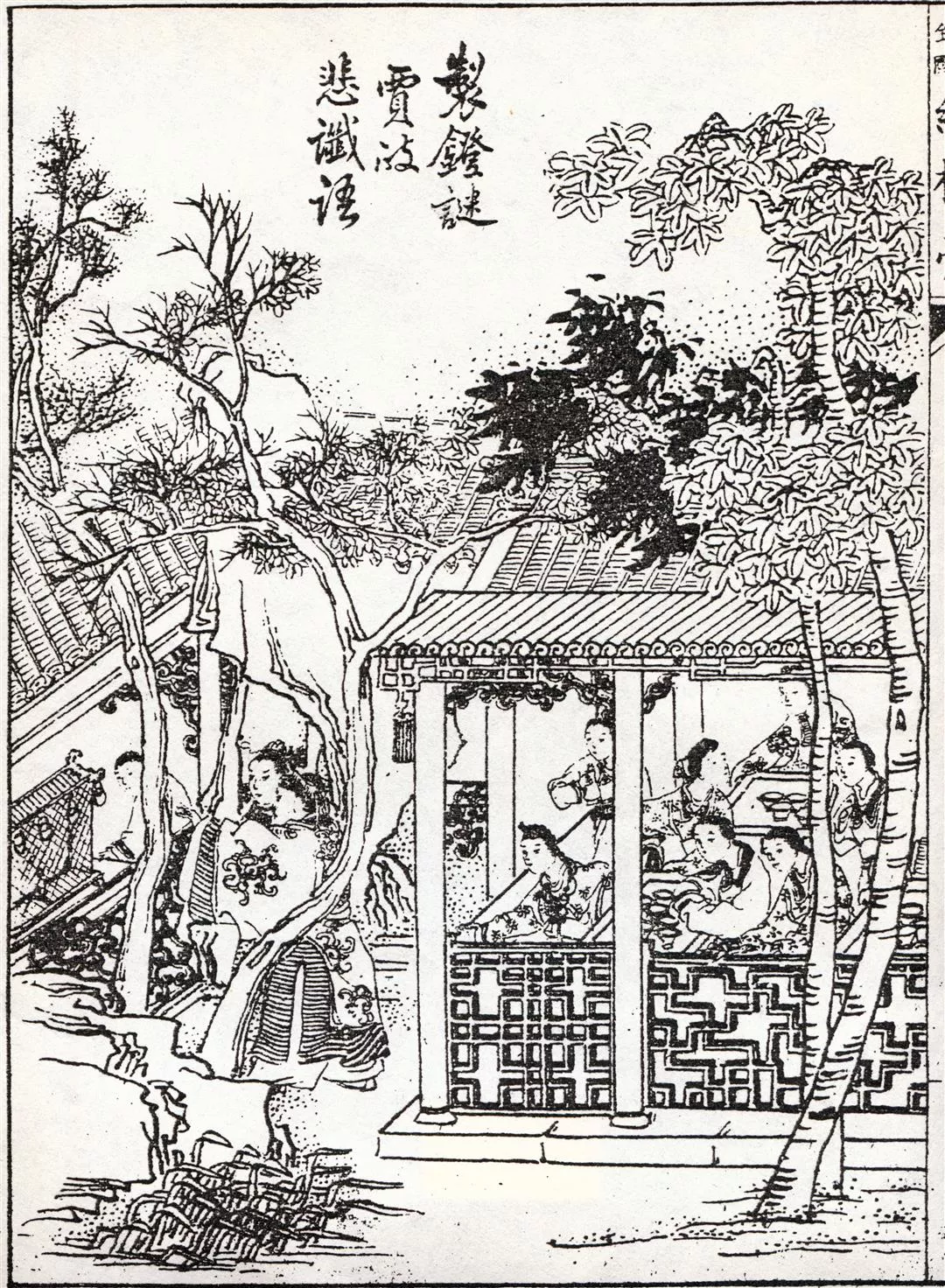

This illustration of a scene of riddle guessing on the Lantern Festival appeared in a late Ching dynasty picture book. (photo courtesy of Yin Teng- kuo)

On the Lantern Festival (15 days after Chinese New Year's), besides eating sweet rice dumplings, setting off fireworks, enjoying the colorful decorated lanterns, and watching the dragon parades and lion dances, Chinese gather in the evening at temples and schools to guess at ingenious riddles hung from lanterns, the so-called "lantern riddles."

Riddles are not, of course, limited to the Lantern Festival. Generations of Chinese children have puzzled themselves over "a thousand threads, a million threads; into the water, they can't be found'' until, after hints and prompting from parents or teacher, they finally come up with "rain." And when first- and second-graders are taught to write, they learn little riddles to help them remember the shapes of the characters.

Riddles even appear in folk songs, such as the popular Taiwanese ditty that goes--

Bite the head

Grab the waist

Light the bottom

And have a taste.

The answer: "smoking a cigarette."

Riddles are always fun, but on the festive, poetic evening of the Lantern Festival, they really come into their own. In every city and town, at any public place, but especially in front of temples, row after row of lanterns with riddles hang in the night air fragrant with the scent of incense and sulfur.

Whether the prizes are generous or meager, the riddles are sure to attract swarms of the hopeful. Not a few come prepared with copies of the Analects, Mencius, the Three Hundred Poems of the T'ang Dynasty, or other reference books, hoping to return home loaded with the spoils of victory or at least not go away empty-handed. Others just come to watch the fun.

Riddles have, in fact, fascinated the Chinese for millennia. When the people of the Shang overthrew the despotic last ruler of the Hsia dynasty in the 16th century B.C., they veiled an allusion to him in a riddle as a secret rallying cry. And a line in the fifth-century work of literary criticism The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons says, "Riddles, by mixing up words, create puzzlement." Riddles based on the structure of Chinese characters appear first in another fifth-century work.

The practice of rewarding a prize to the person who guesses a riddle correctly goes back at least as far as the Emperor Kao Tzu of the Northern Wei dynasty (386--534). He once raised his cup and said--

Three, three across;

Three, three up;

Whoever guesses

Gets a gold cup.

The cup went to a minister who correctly guessed the Chinese character the emperor was describing.

One of the most famous riddles in history appears in an anecdote about Ts'ao Ts'ao, the machiavellian general of the Three Kingdoms Period (220--265). Riding along with his officers, Ts'ao Ts'ao came across a memorial stele inscribed with a famous elegy. Underneath the elegy were eight puzzling Chinese characters.

When Yang Hsiu, one of Ts'ao's subordinates, said he understood their meaning, the general replied, "Don't tell me. Let me think."

Ten miles down the road, Ts'ao Ts'ao came up with the answer. The eight characters, by an ingenious play on their meanings, shapes, and sounds, could be recombined into four other characters saying, "Excellent writing!"--words in praise of the elegy on the stele.

Ts'ao Ts'ao sighed, "Yang Hsiu is cleverer than I am by ten miles!"

Riddles and lanterns were first brought together during the Sung dynasty (960-- 1279). A Sung writer mentions witty poems containing hidden meanings written on silk lanterns to amuse passersby. The name "lantern riddle" originated around that time.

By the time of the Ching dynasty (1644--1911 ), riddle guessing on the night of the Lantern Festival had become extremely popular, and lively scenes are often depicted in contemporary poems and novels. Chapter 50 of the Dream of the Red Chamber describes the fun had by the young mistresses of a wealthy family in thinking up riddles for the Lantern Festival. The author created many original riddles for the chapter, some of which, left without a solution, continue to perplex scholars today.

Lantern riddles come in different categories. The most common are little rhymes that give clues to the structure of the Chinese character to be guessed. A simple example:

Four tall mountains

Top to top;

One river down,

One across.

The answer is field. Look at the characters for mountain 山, river 川, and field 田, reread the riddle, and see if you can understand why.

Riddles with literary allusions are also common. The answer is frequently a quotation from the classics, a line of poetry, or a character or title from a novel or play. The riddle, containing plays on sound or meaning, may itself be a poem.

But riddle material is scarcely limited to character puzzles and literary allusions. History, geography, plants, animals, names, current events, popular songs, TV shows, slang, English, and mathematics all may be used. Some answers do not even involve words at all, but actions.

If riddle guessing is such an art, how can the average person hope to succeed?

"Don't be discouraged," Hsu T'ien-ho, a member of the Kaohsiung Riddle Society says. "Quick wits are important, but so is collecting material. The more you have, the higher your rate of success." Beginning by working a riddle a day, Hsu found himself collecting reference material from the classics, poetry, place names, the movies. . . and organizing it by category into reference books. His friends call him a riddle nut.

Chang Kuo-nan, a mathematics professor at National Taiwan University and a fan of riddles for over 30 years, has another opinion. "The key to solving riddles is nothing more than 'thinking crooked'," he says. Working riddles is a kind of "mental exercise" that strengthens intelligence and comprehension, he believes.

And it is fun. Taiwan now has over more than 10 riddle clubs, according to the latest count, over 1000 members. Members get together weekly or monthly to work riddles, make riddles, and even put out books about them.

But it is at the Lantern Festival that the riddlers really put their talents on display. Some construct riddles, hang up lanterns, set up booths, and help out with the prizes. Others enter the fray personally for a chance to show off.

Expert or no, young or old, Chinese love riddles. And they will be out in force on the evening of February 23rd this year, crowding around the lanterns, hoping to crack the clues, take home a prize, and win a little piece of glory.

Riddles today are usually written on posters and displayed from platforms, not pasted to lanterns as in the old days.

A pavilion displaying riddles is shown on the left of this illustration from Chapter 22 of Dream of the Red Chamber.

While adults concentrate on the riddles, these little tikes, too young to understand, can only appreciate the lanterns. (photo by Wu Che- ching)

The gorgeously dressed women in this painting from a Ching dynasty picture album have taken their children outside to play with lanterns on the Lantern Festival. (photo courtesy of National Palace Museum)

Decorated lanterns give the festival a special, poetic air.

Divers and sundry riddle books represent the fruits of labor of devoted fans.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)