The pioneers of emigration from China to Panama were Chinese migrants of the 1850s who sold themselves into bonded labor on construction of the Panama railway.

Malaria and yellow fever were rampant among the workers building it, and railway coolies of all countries shuddered to hear its name. Approximately 20,000 Chinese laborers worked on the railway and it is said that more Chinese corpses line its course than wooden sleepers. There is still a station on the line called Matachin, whose name means "the dead Chinese."

In 1904, under pressure from anti-Chinese laws passed in the US in 1882, Panama forbade the immigration of Chinese, Turks and Syrians. It was not long however before reduction of the hardworking Chinese labor force began to hamper progress on the Panama canal, so in 1909 Chinese were again permitted to enter the country and expend themselves for the cause of the US-owned Panama Canal Company.

For some the country became their stepping stone to elsewhere in Central and South America. Others stayed on as small traders. The first association that most Panamanians today make with the word "chino" is probably the little Chinese-run corner grocery stores in their country, while the Chinese phrase "chien, chien" is a popular current term there for money.

For over half a century Panama's Chinese were concerned with little more than simply leading a quiet life of hard work. Permanent immigration was not intended. The idea was simply to earn some money and bring a bit of prosperity for the impoverished village back home. The first thought when they did have money was almost always to buy some property near the ancestral home, and find a local girl there to marry and bring back out to Panama. If their children were born in Panama, they would make every effort to send them back home for a Chinese education.

Unfortunately for their ambitions, the 1949 Communist takeover in China saw their home property confiscated, their relatives persecuted and the road home sealed off.

Although history had cut them off from China, Panama was not always a welcoming alternative. Large scale anti-Chinese episodes in 1941 and 1951 led to many local Chinese being stripped of their Panamanian citizenship, and Chinese were banned from practicing in the profitable retail trade, which severely restricted their economic clout.

Fortunately there have been no repeat campaigns allowing the Chinese community to pursue its own health and prosperity in peace. The fruits of the elder generations' labors have rapidly come through in the education of their children, and the lawyers, doctors, business executives and other young Chinese professionals that have emerged in Panama today are their community's new political voice.

[Picture Caption]

Colon station on the Panama railway. Chinese laborers paid a terrible p rice in death and injury for work on building the line. (photo by Vincent Chang)

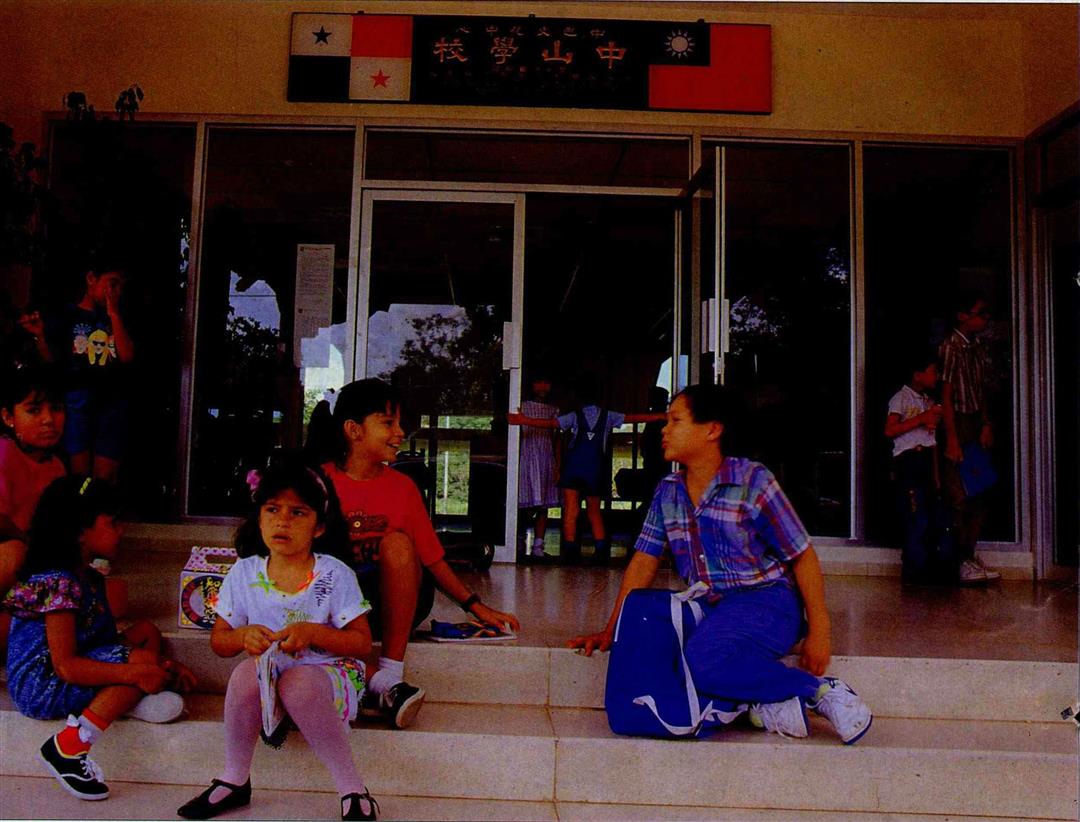

The Sun Yat-sen School, which is a part of the Panama China Culture Cent er, ranges from kindergarten to senior high. There are around 600 Pupils at the school, of whom two thirds are of Chinese origin.