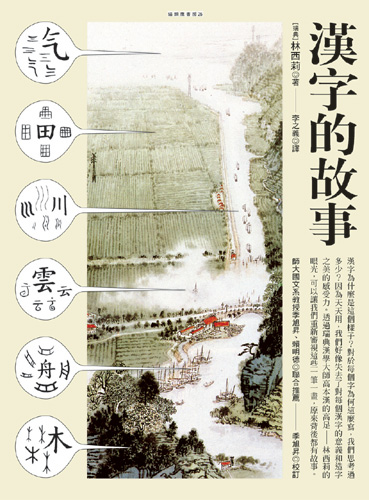

In Defense of Traditional Chinese Characters

Hsiao-yun Kleber-Chang, Germany / tr. by Paul Frank

June 2006

Recently, a news report was widelycirculated among Chinese-speaking people around the world: starting in 2008, the United Nations would cease publishing its Chinese-language documents in both simplified and traditional Chinese characters and would only use simplified characters. In no time, concerned supporters of traditional characters protested the proposed policy change by signing online petitions and distributing e-mail chain letters.

To everyone's surprise, soon afterward a spokesman for the UN Secretariat declared that he knew of no such plan, because since 1971, when the People's Republic of China took over the Republic of China's seat at the UN, all Chinese-language documents and publications produced by the UN had been written in simplified characters. Reports that the UN uses both types of Chinese characters were wrong.

The news originated with Chen Zhangtai, director of the PRC Ministry of Education's Institute of Applied Linguistics. Taiwanese scholars and foreign ministry officials agree that it is worth exploring why Chen chose to spread this piece of "news" at this particular juncture.

Cecilia Lindqvist, a Swedish sinologist with a deeper knowledge of Chinese characters than most Chinese people, follows the great sinologist Bernhard Karlgren in calling traditional characters yuanti zi ("original-form characters"). In Taiwan, the Chinese translation of her China: Empire of Living Symbols enjoyed ten printings within a month of its publication earlier this year.

Professor Roderich Ptak, head of the Institute of East Asian Studies at Germany's Munich University and a long-time observer of cross-strait relations, conjectures, "Perhaps China thinks the time has come to unify the Chinese-speaking world in script as well as in other respects. This may have been a way to put out feelers and announce its intentions."

Stoking the China fever that has gripped the world following two decades of dramatic economic growth in China, the PRC government is exporting large numbers of Chinese language teachers and teaching materials. It is by now beyond dispute that simplified Chinese characters can be seen everywhere and that the use of traditional characters is on the wane. Traditional characters have always been used in Hong Kong, just as they are in Taiwan, but Hong Kong's return to China in 1997 shifted the balance from traditional to simplified characters even further. Many scholars worry that if the current trend continues, overseas Chinese communities and sinologists around the world will soon be using simplified characters. They also fear that surrendering to this reality, the next generation of Taiwanese will also go simplified.

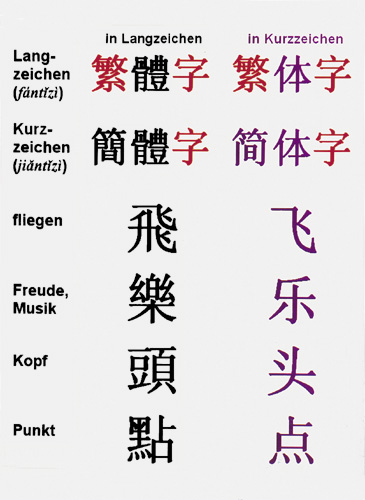

Although simplification was seen at the time as cultural vandalism, Western observers see specific reasons for it having become official policy. After the Chinese Communists established a "proletarian state" in 1949, they faced the challenge of indoctrinating hundreds of millions of illiterate workers, peasants and soldiers in short order. To this end, in 1956 the government launched a campaign to introduce simplified characters. The State Council issued a number of lists of simplified characters, eventually comprising the 2,236 that are in general use today. During the 1967-69 "Smash the Four Olds" (ideas, culture, customs and habits) campaign at the height of the Cultural Revolution, fanatics around the country created all sorts of characters that were simplified to various degrees. Fortunately, after the Cultural Revolution the government prohibited their use.

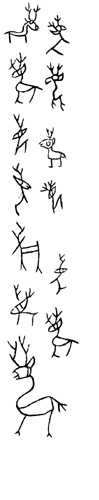

Many pictographs represent animals. The pictograph lu, meaning deer, shown above, developed from depiction such as those at right, of a deer with a dignified bearing and big, inquisitive eyes.

As defined in the PRC, characters were simplified according to nine principles:

1. Retaining an outline of the original shape, e.g., 龟for 龜(gui, "tortoise; turtle") and 虑for 慮(lu, "consider").

2. Adopting a partial feature of the original character and leaving out the rest, e.g., 声for 聲(sheng, "sound") and 医for 醫(yi, "medical doctor").

3. Replacing a component on one side of a character with a simpler component with fewer strokes, e.g., 拥for 擁(yong, "embrace") and 战for 戰(zhan, "war").

4. Replacing a phonetic component with a simpler one, e.g., 惊for 驚(jing, "surprise, alarm") and 护for 護(hu, "guard").

5. Merging two characters into one, e.g., using 里(li, "village"; "Chinese mile") for 裏(li, "inside") as well as 里, and 余(yu, "I, me") for 餘(yu, "surplus") as well as 余.

6. Adopting stroke patterns based on the cursive style of calligraphy, e.g., 专for 專(zhuan, "special"), 东for 東(dong, "east"), 车for 車(che, "wheeled vehicle") and 转for 轉(zhuan, "turn, rotate").

7. Adopting a character's ancient form or a self-explanatory character or associative compound (ideographic character), e.g., 众for 眾(zhong, "crowd"), 从for 從(cong, "follow") and 网(wang, "net") for 網. These ancient-form characters are simpler in graphic structure and accord with the principles of character creation. It is thought that in ancient times they were replaced by more complex forms to give them a more attractive appearance.

8. Replacing a complex components on one side of a character with a simpler symbol, e.g., 鸡for 雞(ji, "chicken"), 欢for 歡(huan, "happy") and 难for 難(nan, "difficult"). In all three cases, the left-hand component has been replaced by 又.

9. Adopting ancient characters, e.g., 圣for 聖(sheng, "holy"), 礼for 禮(li, ceremony"), 无for 無(wu, "without"; "nothingness"), and 尘for 塵(chen, "dust").

Since the launch of China's reform policy in 1978, people worldwide have become increasingly familiar with simplified characters. To boost confidence in simplified characters, the Chinese government recently invited famous centenarian linguist Zhou Youguang to utter the following endorsement: "The popularity of simplified characters demonstrates that simplification was a step in the right direction and has won the approval of most people around the world." In addition, because modern people are forever seeking speed and simplicity, simplified characters seem at first blush to meet the needs of the times. But leaving aside political considerations, from a purely cultural perspective simplified characters have their limitations.

Many pictographs represent animals. The pictograph lu, meaning deer, shown above, developed from depiction such as those at right, of a deer with a dignified bearing and big, inquisitive eyes.

I remember that when I was in high school, my Chinese language teacher would fly into a rage whenever the subject of the PRC's simplified characters came up. He would curse the Chinese Communists as irresponsible wastrels who had squandered the precious historical treasures bequeathed by our ancestors.

That may be laying it on a bit thick, but traditional characters do create an overall aesthetic impression that simplified characters cannot match. For example, any attempt to write Chinese calligraphy with simplified characters produces misproportioned and very unsightly characters.

The increasing use of computers and simplified characters is fast eroding the Chinese cultural heritage. To make matters worse, simplified characters have simply done away with a large number of perfectly good words. No distinction is now made between 胡 (hu, "reckless") and 胡 (hu, "whiskers") with 胡 being written for both of these distinct meanings. Even family names of ancient pedigree have been bastardized. The surnames 傅 (Fu, which also means "teacher") and 蕭 (Xiao, which can mean "respectful" or "serious") are now sometimes written as 付 (fu, "to pay") and 肖 (xiao, "similar")!

Han Xiu, a writer who lives in the US, was born and raised in mainland China, but she has nothing good to say about simplified characters: "When they don't lop off the head they lop off the tail; or else they are missing an arm or a hand or a foot. Homophones whose distinct meanings are clear in traditional characters are lumped together as a single character. What you get is page after page of wrongly written characters. They are a sorry sight."

Nonetheless, Hans van Ess, a well-known sinologist at Munich University, thinks that given international realities, it is natural for the UN to use only simplified characters. After all, Taiwan has no seat and no voice in the UN. Nothing much can be done about this brutal fact. Moreover, publishing separate editions in traditional and simplified characters would cost time and money. No company, organization or agency can afford to do so. Van Ess finds this very regrettable, because it greatly harms Chinese culture. Therefore, he and Professor Ptak insist that students in the Chinese department learn traditional characters which give them direct access to the Chinese classics in their original form. From a sinologist's perspective, a familiarity with traditional characters is a basic prerequisite for engaging in scholarly work.

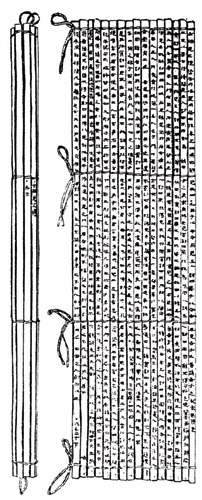

The gradual historical development of Chinese characters--such as ce ("book") from a pictograph of bamboo slips bound together with string, to a mature character with a complex stroke pattern--is no longer apparent in today's characters.

According to Hong Kong political commentator and acclaimed novelist Louis Cha, traditional characters are the quintessence of Chinese culture and a treasure of world civilization. To protect them from the threat of extinction posed by simplified characters, Cha has urged the Taiwan government to apply to have them granted "world cultural heritage" status and to demand that the international community face up to this serious cultural crisis.

It may sound bathetic, but there is no turning the tide. A little over 30 million people around the world use traditional characters, compared to 1.3 billion who use simplified characters. Moreover, because the Chinese government wields ever greater political and economic influence, many worry that traditional characters will be competed out of existence or, like Latin, become an exclusive script understood only by scholars, professors and experts.

In the past Hong Kong used traditional characters, but given the growing influence of the PRC since the 1997 handover, Hong Kong may soon capitulate. If it does, Taiwan will become the last bastion in the defense of traditional characters. The PRC government views Taiwan as the chief obstacle to the simplification of Chinese characters. It even suspects that many Hong Kong people have not accepted simplified characters because they have come under the sway of Taiwan, and argues that in resisting simplified characters, Taiwan is confusing script reform with politics.

Scholarship rigorously seeks truth from facts. Scholars inquire into reality as it really is and cannot answer questions based on received dogmas, the conformism of the majority or the notion that might makes right. Therefore, most members of the international sinological community do not accept the wholesale adoption of simplified characters.

Professor Ptak says, "Although our departmental library contains classical works published in simplified-character editions, we cannot give up traditional characters. I expect students in the Chinese department to continue to use both kinds of characters and to have a good grasp of both. Unless they are able to read classical works and pre-modern primary sources, how can they pursue scholarship? Whereas simplified characters have a history of a few decades, Chinese culture has a history of thousands of years. Most international research in sinology focuses on the history that preceded the invention of simplified characters." Because many simplified characters violate established principles of character formation and have no logic or rule behind them, Professor Ptak cannot bear the sight of them. He is firmly opposed to the simplification of Chinese characters.

In fact, many China scholars Professor Ptak is in contact with feel the same way. Professor Ptak says, "In some cases simplification is of no importance, but some characters really cannot be simplified!" The trouble is that over the past 50 years, simplified characters have become a matter of habit and face for the Beijing regime. It would be virtually impossible to revert to traditional characters. The ideal solution would be to let politics be politics and scholarship be scholarship. Experts on both sides of the Taiwan Strait could come together to consider the issue on its merits and find a compromise. Let characters that can be simplified be simplified but preserve the original form of characters that cannot be simplified or have been unreasonably mutilated by simplification. The alternative will confuse foreigners and leave Chinese people unable to read their own classics, which would be a great loss. A serious cultural rupture is already evident in China. Most young people are unable to appreciate calligraphy and paintings by famous artists of past dynasties.

The gradual historical development of Chinese characters--such as ce ("book") from a pictograph of bamboo slips bound together with string, to a mature character with a complex stroke pattern--is no longer apparent in today's characters.

To a professor of sinology, traditional characters are no stumbling block, but foreign students of Chinese moan that "going from traditional to simplified is easy but going from simplified to traditional is hard." When one student, named Ute, entered the sinology department she was very glad to discover simplified characters. She felt the structural complexity of "long-form" characters made them intimidating, and "short-form" characters were much more convenient. A couple of years later, when her professors required her to learn traditional characters, she complained that she could not cope with them.

Are simplified characters that convenient? Many German students of Chinese report the following experience: "When you start learning simplified characters, you are pleased to find they have fewer strokes, which saves trouble. But later you discover there's no real advantage to simplified characters because too many of them are alike and you get them confused. Or else there's one character with several completely unrelated meanings. It's very confusing." For example, the syllable mian in the words 麵包 (mianbao, "bread") and 麵條 (miantiao, "noodles") is traditionally written with the character 麵, which means "flour," but in the simplified script it is written with the character 面, meaning "face" and is traditionally reserved for the word 臉面 (lianmian, "face"). The syllable song in the words 輕鬆 (qingsong, "relaxed") and 松樹 (songshu, "pine tree") is traditionally written with different characters that indicate the two distinct meanings, but in the simplified script it is written 松 in both cases, thus eliminating the distinction. Deprived of their original meaning and internal logic, Chinese characters are insipid.

Just when simplified Chinese characters seem to be taking over the world, a Chinese translation of China: Empire of Living Symbols by Swedish sinologist Cecilia Lindqvist has been published in Taiwan. Tracing the origin of Chinese characters from their beginnings as inscriptions on oracle bones and ancient bronzes, this book is a timely shot in the arm for champions of traditional characters. Highly praised by the Western sinological community, it was quickly translated into English, French, German, Norwegian and Finnish, and has sold 850,000 copies. Lindqvist has enabled those of us who use Chinese characters every day to see and appreciate our own script with new eyes.

Compared to the aesthetic perfection of traditional characters, simplified characters look like they are missing an arm or a leg.

In sum, both Professor Ptak and Professor van Ess hope that Taiwan will stick with traditional characters. Van Ess says, "Once you have learned traditional characters, it's easy to recognize simplified characters; going the other way round is more difficult. Taiwan ought to be glad that it enjoys this advantage." Sounding a note of optimism, van Ess says that although political factors play a role in the contest between traditional and simplified characters, politics is a fickle business and there is no such thing as forever. Chinese dynasties have come and gone; the next political party or leader that rises to power could quickly make a major change of policy.

Although the position of simplified characters seems unshakable, in recent years there has been a quiet traditionalist trend in the mainland. Some academic treatises (particularly in literature and history) are now published in traditional characters; it has also become fashionable for shop and restaurant signs to be written in traditional characters. Among young social climbers visiting cards printed in traditional characters are all the rage, because they give the impression that their owners are better educated and a cut above the rest.

In fact, since the Chinese government initiated its reforms it has not launched any more campaigns to "Smash the Four Olds" or "Overthrow the Confucian Shop," and has begun to stress China's traditional culture. It is therefore unlikely that traditional characters will be abandoned altogether. Van Ess reasons, "The main advantage of simplified characters is that they are easier to learn and quicker to write. But people no longer write by hand. Now that everyone uses computers, what possible advantage is there to simplified characters?"

For this reason, van Ess suggests that Taiwan ought to quickly develop easier input systems that will facilitate the use and spread of traditional characters. Unable to think of a good reason to support simplified characters, he concludes: "Traditional characters are not dead yet."

Professor Ptak is also hopeful of a return to traditional characters. He takes a historical perspective: "Writing systems and language change over time and space. Chinese characters have in fact undergone a gradual process of simplification over millennia. Overly complex and difficult characters are used less and less. A few years ago, the German authorities launched a major new spelling reform, but they soon discovered it was no good, and are now fast reverting to many of the old spellings. As people use by turns traditional and simplified characters they will perhaps find a balanced and reasonable middle way." Ptak adds, "Besides, fortunes change. Germany has recently witnessed a revival of interest in learning Latin. The day may come when those who insist on using simplified characters will realize that traditional characters have the strength of history behind them."

Seeing these sinologists' unswerving confidence in traditional Chinese characters is truly gratifying. But we have to do our part too. It would be disgraceful if the day came when we had to rely on foreign sinologists to defend our own culture!