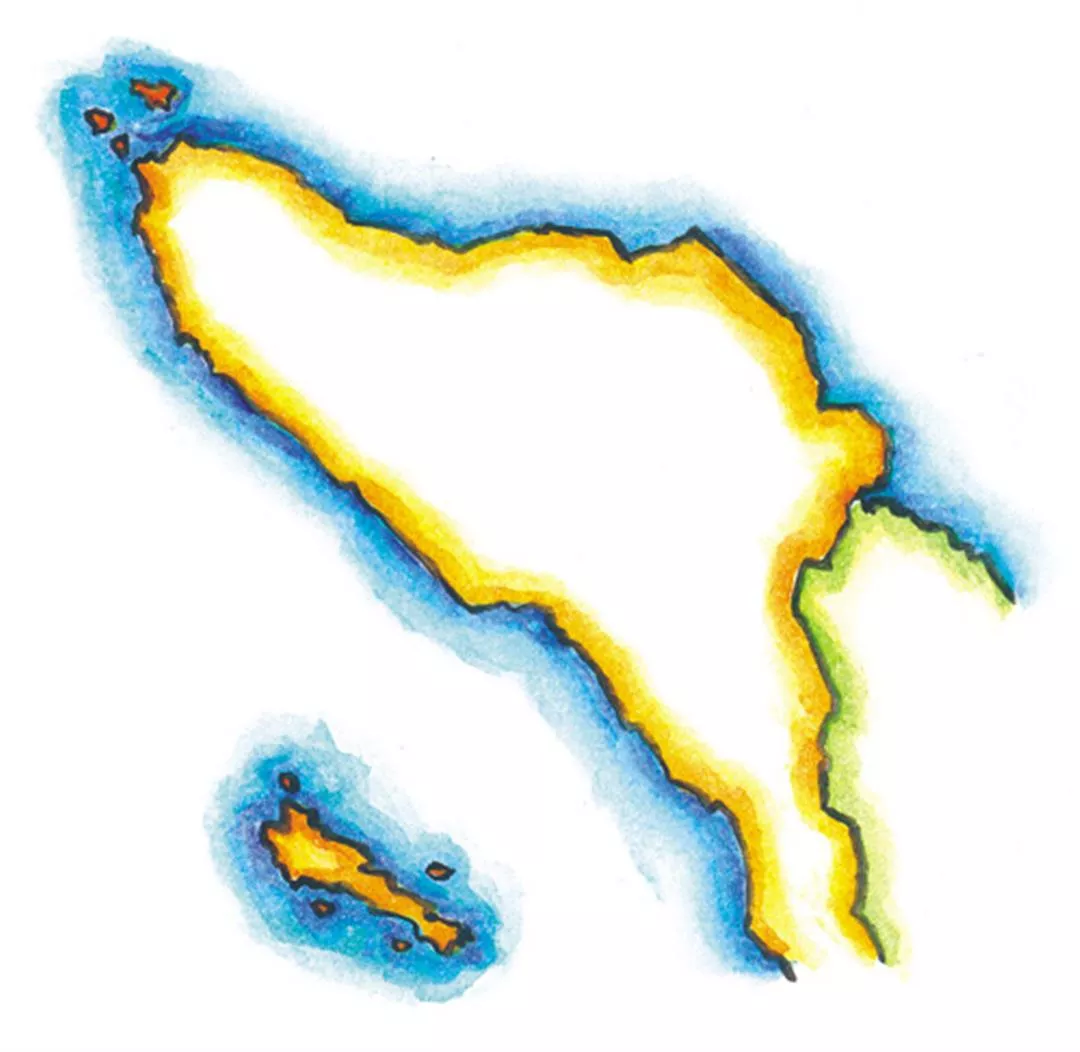

Aceh is no murderous and rebel-lious wild, / Aceh is no poor, xenophobic hinterland, / She was once Mecca's civilized porch, / She was also a rich and flourishing frontier.-Lin Cheng-hsiu

As Lin Cheng-hsiu, vice chairman of the New Taiwanese Cultural Foundation, describes in the excerpted poem above, written as the Aceh Peace Treaty was being signed on August 15, 2005, relief organizations from around the world flooded Aceh in the wake of the tsunami. This influx of foreign relief workers helped lift the veils of mystery from Aceh, and generated sympathy among many international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for the Free Aceh Movement that had been battling the Indonesian government for nearly 30 years.

Formed in Sweden in 1976, the Free Aceh Movement grew out of the many guerilla wars fought in the region since the 1950s. What has driven the more than 50 years of bloodshed in Aceh? How long can the current ceasefire, wrought by the tsunami, last?

The sky over Banda Aceh is still dark at a bit after 5 a.m., but early morning prayers at the Baiturrahman Mosque are already marking the start of the day in Aceh's provincial capital.

The revered mosque was left largely unscathed by the tsunami that leveled half the city in 2004. Towering above the mud and debris, the mosque saved around a thousand local residents who sought refuge within its walls. It also served as a source of comfort and hope to the community. In the wake of the disaster, wave after wave of Muslim faithful came here to weep and pray for lost loved ones, finding in their devotion the strength to carry on.

Many in Aceh say, "It was a test given us by Allah." But they do not speak against God. Instead, they think the tragedy was perhaps a punishment for the years of bloody warfare. Now, the people of Aceh's devotion to Islam is helping them bear their trials, just as in days past their faith carried them through many glorious battles.

Banda Aceh's vast farmlands produce plump, juicy papaya and coconut, but the life of its typical laborer is very hard.

Aceh Province covers approximately 570,000 square kilometers. Its more than 2,300 mosques and nearly 10,000 prayer rooms and prayer halls provide its 4 million residents, approximately 98% of whom are Muslims, places for worship. Even Banda Aceh's public spaces, including the airport and restaurants, include quiet prayer halls. Five times every day, locals set aside their tasks, take off their hats and shoes, and pray.

The signs of conservative Muslim culture are everywhere in Aceh: Women wrap their entire bodies in clothing and cover their faces with veils in spite of the sweltering heat. Men's slacks reach at least to their knees. Unmarried men and women can only meet when accompanied by others. After completing primary school, many children are sent away to religious boarding schools to study the Koran.

Perhaps because of Aceh's strongly religious character, outsiders often blame its independence movement on religious conflict. "This oversimplifies the complexity of Aceh issues," says Chen Li-fu, an assistant professor of political science at Aletheia University who is one of the few Taiwanese academics to study Aceh's separatist movement. Chen says that mainstream Western scholarship contrasts Aceh's ties to fundamentalist Islam and the pro-Western stance of Indonesia's government. It therefore sees the Aceh conflict as a clash between modern Western civilization and ancient Islamic culture. But when one recognizes the fact that Indonesia is the world's largest Muslim nation, it becomes clear that the conflict is not, at its heart, a religious one.

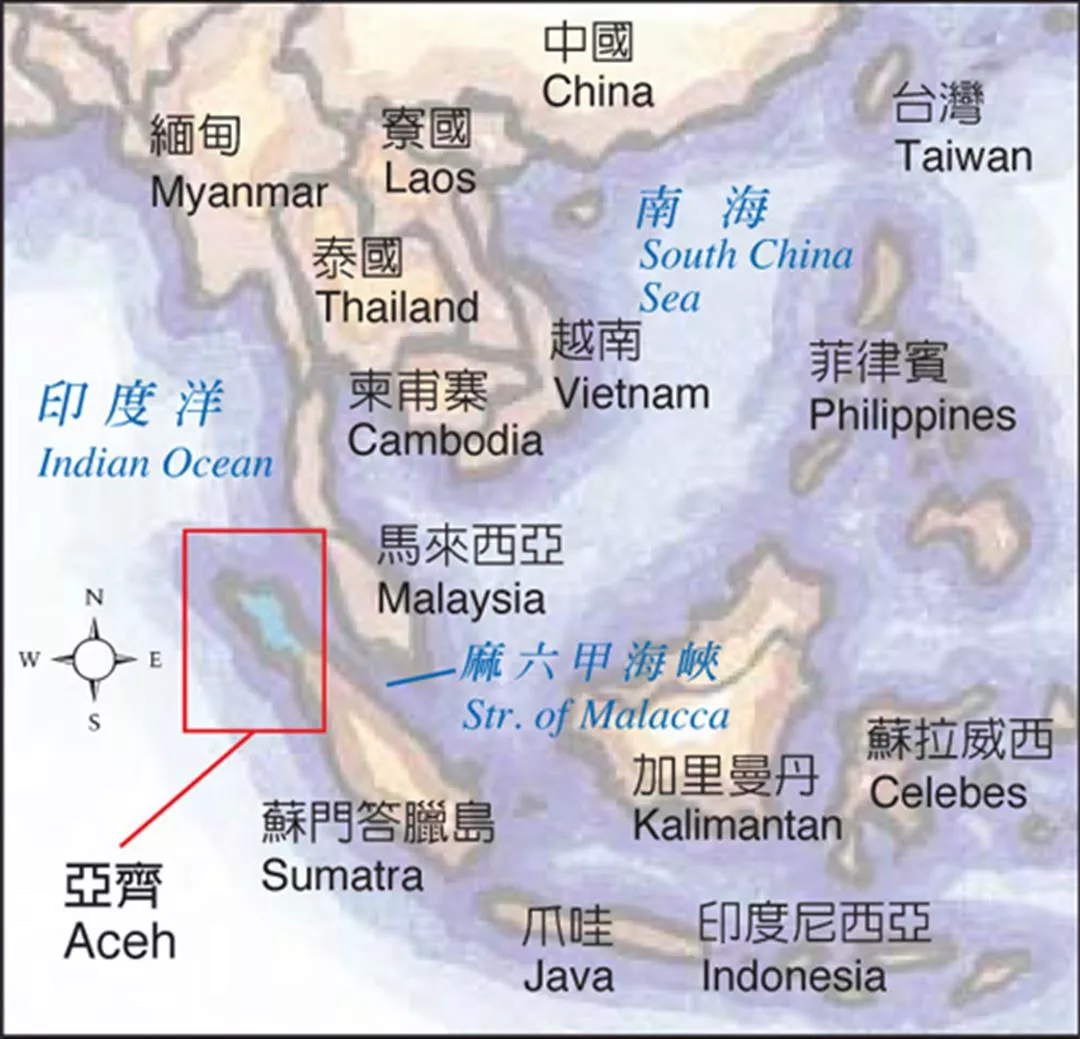

"Aceh's history and its political relationship to Indonesia make plain the reasons the province is seeking independence," says Chen. He explains that Indonesia as a nation is a product of the imagination of the colonial-era Dutch, who were a major maritime power in the 17th century. The Netherlands took the territories they controlled-independent kingdoms with long histories such as Java and Sumatra, indigenous tribes of various sizes, and pirate-controlled islands, and lumped them all together into the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). The Dutch went even further, creating an Indonesian language based on Malay to create a sense of unity and to promulgate laws, thereby laying the foundations for the modern state.

Aceh in northwest Sumatra remained independent for much of the nearly 300 years during which the Dutch controlled what was to become present-day Indonesia. The battle for Aceh, which commenced in earnest during the final stage of the Dutch unification of Indonesia, lasted 40 years. The Dutch finally extended their control into the province in 1912, but at a heavy cost.

With the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1939, the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies. Aceh took advantage of the turmoil to break free of Dutch rule, running the colonialists out in only four days. "The Acehnese were under Dutch control for only 30 years. There wasn't much time to brainwash them, so they never came to think of themselves as 'Indonesians,'" explains Chen.

Part of the reason Aceh was able to remain independent while the Dutch were conquering the rest of Indonesia was that its sultanate was built upon a strong military and economic foundation.

Aceh has abundant natural resources, including crude oil, palm oil and coffee, but is among Indonesia's poorest provinces. The Free Aceh Movement formed in large part to address the economic fleecing of the province.

"A 'sultan' is a ruler under Islamic law," says Chen. "The word means 'protector of Islam." Chen explains that Islam spread from the Middle East to India in the 7th century, spreading rapidly along maritime trade routes and river valleys. The spice trade then carried Islam across the Bay of Bengal to Indonesia. Aceh, which was the nearest point to India on these trade routes, became an important base for Muslim missionaries from Iran, Turkey, and India.

After reaching Aceh, Islam continued to spread eastward, establishing footholds in Sumatra, Malaysia, southern Thailand, Borneo, and the Philippines. Known for centuries as "Mecca's porch," Aceh is clearly an important part of the Muslim world.

"We don't know exactly when Islam came to Aceh," writes Liu Ching-yun, an alumnus of Tamkang University's Graduate Institute of Southeast Asian Studies who wrote his master's thesis on Aceh's separatist movement. "But by the 13th century, Aceh had already established a sultanate." The sultanate wasn't very powerful in its early years, but that changed in the 16th and 17th centuries, when its strategic location helped it displace Malacca as the hub of East-West trade. It then used its economic and military might in a "holy war" to create an Islamic kingdom spanning the Straits of Malacca. During the golden age of sea power, Aceh signed friendly agreements with Britain, then a major maritime power, and had official exchanges with nations including the US and France. "These agreements show that the Aceh sultanate was an independent, sovereign nation widely acknowledged by the international community."

Deep-rooted in the people of Aceh is an acute sense of the province's glorious history and a devout belief in Allah. They fought shoulder to shoulder with the Javanese to throw off the Dutch yoke after World War II, thereby helping to bring the nation of Indonesia into being. When Sukarno then declared Indonesia a secular republic rather than a Muslim nation in 1950, they felt cheated and refused to be part of it.

"The people of Aceh feel they were betrayed," says Chen. They contributed the most to the war for independence from the Dutch, but all they got from the new government, whose power base was Java, was Indonesian citizenship. Aceh's request to be independent was rejected and its use of Islamic law prohibited. In 1953, military resistance to Indonesian rule broke out across virtually the entire province, and guerilla conflicts large and small raged for decades.

When the Indonesian government began also ravaging Aceh's economy in the 1970s, the Free Aceh Movement took the stage.

Chen says that when Suharto, a military strongman, took over the Indonesian government in 1965, he emphasized foreign investment, prioritized economic development, made the military into a force for stability, and stocked his party with bureaucrats and soldiers. Indonesia's industrial output rose dramatically in the 1970s and the country prospered. But these businesses were all under the control of foreign investors, corporations with military ties, and ethnic Chinese, and none of the benefits of development trickled down to ordinary citizens.

During Suharto's 33-year reign, his family's privileges extended far and wide, and Javanese ended up with disproportionate control over the nation's resources. For example, when the oil and gas industry came to Aceh, they gave most of the oilfield management positions to Javanese, and relegated the Acehnese to menial work. The Acehnese were still more upset when the industry's large foreign-exchange earnings were used to develop Jakarta, not Aceh.

Liu writes in his thesis that Aceh is among Indonesia's richest region in terms of natural resources-it produces large amounts of natural gas, palm oil, coffee, and rubber-but the Acehnese themselves are among Indonesia's poorest people.

"Our educational standards have fallen," says Sayed Husaini, a former guerilla now resident in of one of the communities the Tzu Chi Foundation has built in Indonesia. "Kids have no idea how advanced the rest of the world is." Husaini says he knows many Acehnese have been very successful in business outside of Aceh and wonders why the hardworking, intelligent individuals who remain must endure such poverty and backwardness in their own land. The unfairness of the situation motivated him to join the Free Aceh Movement. It also explains how the movement grew from the 70-some intellectuals who were its original members to more than 5,500 official members and 30,000 guerillas in 2003.

After laying down their arms, some of the Acehnese guerillas moved into Tzu Chi's Great Love villages. Said Muhammad (second from left), a spokesperson for the Free Aceh Movement, had heard good things about Tzu Chi and went to see for himself. Also pictured are Tzu Chi volunteer Aida Angkasa (far left), former guerilla Sayed Husaini (third right) and two other former guerillas (far right and second right) who now live in the village.

"After the tsunami, Aceh had to accept peace," says Chen. He explains that the disaster destroyed so much of the provincial infrastructure and killed so many Acehnese residents and resistance fighters that the public had nothing left with which to support the movement.

Peace talks went smoothly after the tsunami. Since the ceasefire was signed in Helsinki in August 2005, the province has begun taking steps towards autonomy. Though it has abandoned its pursuit of diplomatic and military sovereignty, it is running its own administration within its borders-promulgating laws made by Aceh's own legislature and establishing its own Islamic courts. However, oil remains an issue. With oil prices soaring, nations around the world are racing to get their hands on oilfields. The situation is no different in Indonesia, OPEC's only Asian member. Aceh's oil resources have thus become a source of problems and introduce a new variable into its pursuit of autonomy.

"On a more positive note, the tsunami made the world more aware of the Aceh issue than it has ever been before," says Chen. In the past, the West was largely indifferent to the problem, forcing the Free Aceh Movement to seek support from the Middle East. This resulted in its members being labeled radical Muslims, and, after 9/11, "international terrorists." "They really were smeared," says Chen.

The aid that the international community, human-rights organizations, and NGOs have provided to Aceh has brought with it Western notions of democracy and human rights. It has also shone a light on the Aceh conflict. As the destruction wrought by the tsunami fades into memory, will the Indonesian government and Free Aceh Movement continue to seek diplomatic rather than military solutions, thus sparing this troubled land more bloodshed? Will they work together to bring it the fruits of real peace and prosperity? The Acehnese and the world are praying that they do.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)