Once Again Upon a Time-Ginza in Taipei

Kuo Li-chuan and Teng Sue-feng / tr. by David Smith

July 2011

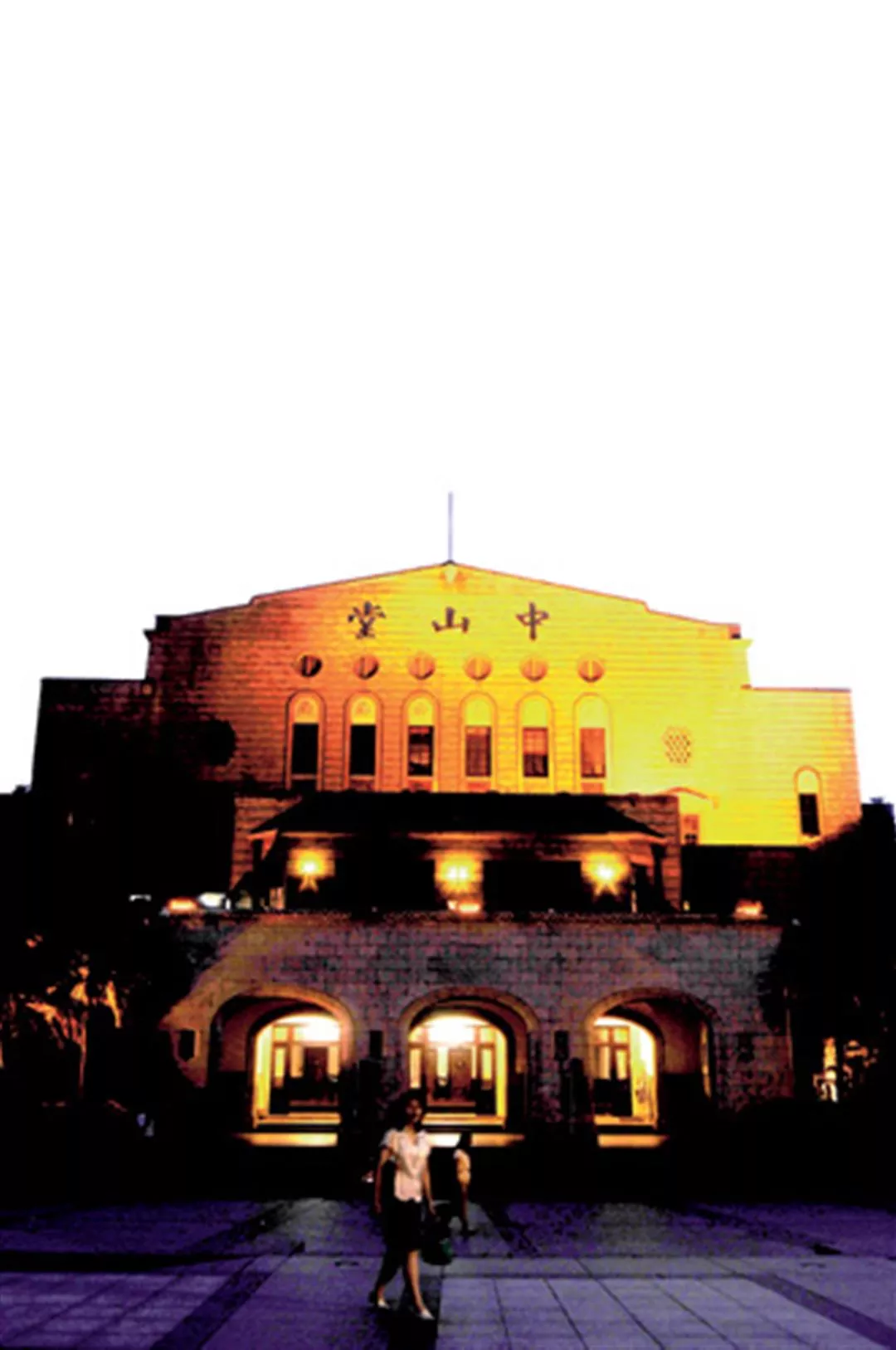

If you happened to be walking along the busy streets of Taipei this past May through the plaza at No. 98 Yan-ping South Road, not far from the Xi-men-ding district, your attention would almost certainly have been drawn to the huge banners announcing the beginning of two exhibits-"The Story of Zhong-shan Hall-A Permanent Exhibition" and "Tai-pei -Ginza-A Century of Memories"-being held at Zhong-shan Hall, a Class 2 Historical Site redolent of memories for Taiwan's elites and the hoi polloi alike. The site has witnessed many a political and intellectual sea change in Taiwan over the decades.

This historic building has now stood silently for 75 years and been through both heyday and oblivion. Today it is making a comeback as a cultural center.

Zhongshan Hall is located in a district that was called "Sa-kae-cho" during the Japanese colonial period, otherwise known as "Tai-pei Ginza" because it was the flourishing heart of old Tai-pei. The district included streets known today as Heng-yang Road, Bao-qing Road, and Bo'ai Road. In those days, Bo'ai Road was lined with big fabric shops. Also in the neighborhood were Ki-ku-moto (Taiwan's first department store, housed in a building used today by Cathay United Bank), the Taiwan Daily Newspaper (later known as the Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News), the Bank of Taiwan, and the Governor-General's Office (now the Presidential Office Building).

History follows a path chiseled out by the circumstances of the times, and so Zhong-shan Hall underwent many a transformation over the years.

In the late 19th century, the Qing authorities built a wall around the city of Tai-pei. Taiwan's first provincial governor, Liu Ming-chuan, came to Taiwan and set up his government headquarters at the Taiwan Provincial Administration Compound, on the same site that would later be home to Zhong-shan Hall.

Zhongshan Hall has finally returned to its original function as a cultural center.

It was here, after the Japanese entered Tai-pei in 1895, that the ceremony took place in which China handed Taiwan over to Japan. The compound then served as the temporary Office of the Governor-General, until the construction of a permanent one was completed in 1919.

In 1928, to commemorate the accession of Emperor Hirohito to the throne, and to provide a venue for cultural activities, the Japanese made plans to demolish the temporary Office of the Governor-General and build a new structure on the site, but part of the compound was moved outside the city walls (to the site of present-day Taipei Botanical Garden) and rebuilt in the style of a traditional Taiwanese san-he-yuan structure.

It is no longer known how exactly the original Taiwan Provincial Administration Compound was laid out, but the Provincial Administration Compound Museum now on the grounds of the Tai-pei Botanical Garden measures seven archways wide along the front, and runs three courtyards deep. Indoors, the compound features an impressive row of columns, with a moderately curved roof ridge and short flying eaves. It was a building of elegant simplicity.

The Taipei Assembly Hall that the Japanese were preparing to build was to be a public activity center. Its function, in other words, would be much like that of the cultural centers now found in counties and cities throughout Taiwan.

Work on the Taipei Assembly Hall commenced in 1932. With the hall only partially complete, the authorities chose it as the venue for a Taiwan Expo in October 1935 to celebrate 40 years of Japanese rule in Taiwan. It was a massive event, on the scale of the international expositions of the West, lasting two months. The Assembly Hall was finally completed in November 1936. The four-year project, which cost ¥980,000 and employed the services of 94,500 people, was one of the most modern of the public buildings constructed during the Japanese colonial period.

In 1945, in connection with the Surrender of Japanese Forces in the China Theater, Japan handed Taiwan over to the Republic of China in a ceremony held at Zhongshan Hall (upper right). As Rikichi Ando (above), the last Jap-an-ese governor-general of Taiwan, signed the Instrument of Surrender inside the hall, multitudes congregated outside, filled with the excitement of victory. In the 1950s, Chiang Kai-shek (left) chose Zhongshan Hall as the venue when he met with a large group of soldiers decorated for heroic achievement in adversity.

The Taipei Assembly Hall was designed by Kaoru Ide, chief of the Construction Section of the Taiwan Governor-General's Office, and the Japanese architect who worked longer than any other in Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period-. He was a leading light among a second generation of Japanese architects to study in the West. Other important works by Ide include a Presbyterian church on Zhong-shan South Road, as well as the old library and the College of Liberal Arts at National Taiwan University.

The completed Taipei Assembly Hall was a four-story steel-frame building covering a site of 1,237 ping (roughly 4,082 square meters), with a total floor space of 3,185 ping. In broad profile, it looked a bit like a bunch of building blocks stacked one upon another. Viewed from the south, it looked rather like the Taipei World Trade Center of a half-century later. For masonry, the builders employed steel-reinforced concrete, which was surfaced with light-green tiles, described as "national-defense green" in color because a militaristic Japan often chose tiles of this sort for defensive purposes as it aggressively expanded its territory.

Lee Chien-lang, a professor in the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at Chinese Culture University, explains the significance of the "national-defense green" tiles. The best-known examples of structures faced with tiles of a "national-defense color" are the dark red buildings at National Taiwan Normal University and the yellow-brown buildings at National Taiwan University. The facing tiles on the buildings featured a ridged surface designed to prevent the tiles from reflecting light in a manner that would aid bombers in the event of an aerial attack.

But while the exterior of the Taipei Assembly Hall presented a monotonous color scheme, the architecture itself was quite varied in style. Kaoru Ide provided the big building with a huge, Greek-style gabled facade and a Spanish-style portico. To these and other Western elements, he added such Asian touches as glazed roof tiles, corbel brackets, diamond-patterned fang sheng air vents, Taiwanese-style red ceramic tiles, Japanese wooden windows, and domed ceilings modeled after those found in Islamic mosques. The architect was clearly intent on breaking away from the imitation of European styles that had been very much in vogue ever since the Meiji Restoration.

The 2,000-seat auditorium in the -newly built Taipei Assembly Hall was often used to put on Japanese kabuki theater. In the year of its completion, the widow of Taiwanese sculptor Huang Tu-shui donated his Water Buffalo sculpture to the Assembly Hall, and the bas-relief work was installed on the wall of the central staircase. It was the first time ever that a work by a Taiwanese artist had graced a government building.

By today's standards, Zhong-shan Hall doesn't look all that imposing, but Lee Chien-lang stresses that when the Japanese authorities rolled out their urban development plan for Taipei in 1932, they were hoping to build a city totally unlike the cramped districts of -Meng-jia, Cheng-nei, and Da-dao-cheng. The plan called for a new city of 600,000 to grow eastward from the banks of the Dan-shui River. "The ambition of the authorities was quite evident, given that Taipei only had a population of 200,000 at that time."

Designed by the Japanese architect Kaoru Ide, Zhongshan Hall is a patchwork of architectural styles from both the East and West, including Taiwanese-style air vents featuring a diamond-grill pattern. The archway over the front entrance is decorated with a heraldic decoration.

Then Japan was defeated in war in 1945 and Taiwan was returned to Chinese rule. It was at the Taipei Assembly Hall that Chen Yi, Chief Executive of Taiwan Province (acting on behalf of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, Supreme Commander of the China Theater), accepted Japan's surrender from Ri-ki-chi Ando, Commander of the Japanese Tenth Area Army in Taiwan. Later that same year, the Taipei Assembly Hall was officially renamed Tai-pei Zhong-shan Hall.

Unfortunately, just a bit more than one year after the Nationalist government took over the administration of Taiwan, tension and mistrust between the new rulers and the local populace led to the 228 Incident.

As violence spread, local elected representatives and intellectuals in Tai-pei gathered in Zhong-shan Hall and established the "228 Incident Response Committee." Members called for a peaceful resolution to the conflict, and Zhong-shan Hall became an island-wide political focal point.

Professor Chen Fang-ming of the Graduate Institute of Taiwanese Literature at National Cheng-chi University, who has authored an article on the history of the Tai-pei Assembly Hall and Zhong-shan Hall, explains: "The committee put forward 42 political demands focusing primarily on Taiwanese self-rule and the institution of democratic politics. They called for freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of association, and demanded an end to the system of government monopolies over selected goods." However, the call from Zhong-shan Hall for local self-rule elicited a hostile response. A bloody massacre ensued, and few of those present at the gathering got by unscathed. In the post-war period, Zhong-shan Hall came to symbolize centralized power.

From the tumultuous 1950s and 60s until the end of martial law in 1987, Zhong-shan Hall was where the National Assembly met, the Legislative Yuan convened, and foreign dignitaries were received. Notable visitors included US vice-president Richard Nixon, South Korean president Syng-man Rhee, and South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem. In addition, Zhong-shan Hall saw the signing of the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty and the inaugurations of the second- through fifth-term presidents of the ROC. Because so many important historic events have taken place at Zhong-shan Hall, the Ministry of the Interior named it a Class 2 Historical Site in 1992.

In 1945, in connection with the Surrender of Japanese Forces in the China Theater, Japan handed Taiwan over to the Republic of China in a ceremony held at Zhongshan Hall (upper right). As Rikichi Ando (above), the last Jap-an-ese governor-general of Taiwan, signed the Instrument of Surrender inside the hall, multitudes congregated outside, filled with the excitement of victory. In the 1950s, Chiang Kai-shek (left) chose Zhongshan Hall as the venue when he met with a large group of soldiers decorated for heroic achievement in adversity.

However, the building at that time served mostly political purposes, with just a few exceptions. It was a transitional period in which the power of the general public was only gradually coming into play. Performance halls capable of seating really big audiences had not yet been built, so the aging Zhong-shan Hall still retained some of its cultural significance.

After its establishment in 1973, Lin Hwai-min's Cloud Gate Dance Theatre put on a show to a packed house at Zhong-shan Hall. The occasion turned out quite memorable, most notably for Lin's departure from local custom by asking the audience not to snap photos, and his immediate halt and restart of the performance when someone in the audience disregarded his request! Then in 1975, the folk singer Yang Hsien held a concert at Zhong-shan Hall, where he sang nine songs consisting of lyrics adapted from the poetry of Yu Kuang-chung. All the songs he performed at the hall were later released in a best-selling album. In 1982, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a Russian exile and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, gave a speech at Zhong-shan Hall entitled "To Free China." Taiwan was still under martial law at that time, and few in the audience could understand Russian, so those in the auditorium must have been feeling a complex mix of emotions as they followed the subtitles and contemplated the words of the philosopher.

Today, the plaza outside the main entrance to Zhong-shan Hall is festooned with multicolored lights, and nearby Heng-yang Road and Zhong-hua Road teem with pedestrians and vehicles. Cafe Astoria on Wu-chang Street, since serving its first cup of coffee in 1950, has played host to literary luminaries such as Kenneth Pai, Huang Chun-ming, and Chou Meng-tieh, who met here and found inspiration for many a work of literature.

With the power base of the authoritarian regime beginning to crumble, the National Assembly moved its meeting place in the late 1980s to Chung Shan Hall on Yang-ming-shan. After that, Zhong-shan Hall sloughed off its political associations and became a purely cultural venue.

The auditorium at Zhongshan Hall features the famed Water Buffalo sculpture by the Taiwanese artist Huang Tu-shui. It was the first time ever that a work by a Taiwanese artist had graced a public building.

After several renovations in the 1990s, Zhong-shan Hall's path to revival came into focus, with the building's administrators redefining it as a center for cultural activities and the performing arts. The semicircular plaza outside the building has been the venue for poetry festivals, tap dance, folk music performances, and much more. Local residents often come to the plaza with family and friends to relax there in the evening.

After the Taipei Chinese Orchestra moved out of Zhong-shan Hall in 2010, the Tai-pei City Government spent NT$30 million on another renovation project, and the building just reopened to the public this past May. In order to re-establish the building as a Tai-pei cultural landmark, Zhong-shan Hall reopened with a special exhibit entitled "Tai-pei Ginza-A Century of Memories," in which the antiquarian Zhuang Yong-ming draws upon his massive collection of maps, postcards, matchboxes, and other household items from different historical periods to take visitors on a journey back in time to get a glimpse at some of the nitty-gritty details of life over the past century in Taipei.

A primary locus of political power during the late-Qing and Japanese colonial periods as well as the first few decades under the ROC, Zhong-shan Hall now looks back upon its history from the perspective of its new identity as a symbol of local culture. As such, it provides an excellent example of how the meaning and function of a given space can change over time.

In 1945, in connection with the Surrender of Japanese Forces in the China Theater, Japan handed Taiwan over to the Republic of China in a ceremony held at Zhongshan Hall (upper right). As Rikichi Ando (above), the last Jap-an-ese governor-general of Taiwan, signed the Instrument of Surrender inside the hall, multitudes congregated outside, filled with the excitement of victory. In the 1950s, Chiang Kai-shek (left) chose Zhongshan Hall as the venue when he met with a large group of soldiers decorated for heroic achievement in adversity.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)