New Perspectives:The 60th Anniversary of the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty

Teng Sue-feng / photos courtesy of the Academia Historica / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

September 2012

August 5, 1952 was an important day for the ROC: On that date the Treaty of Peace between the Republic of China and Japan (a.k.a. the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty or the Treaty of Taipei), which had been previously signed at the Taipei Guest House by ROC Minister of Foreign Affairs Yeh Kung-chao and Japanese representative Isao Kawada, took effect with the exchange of instruments of ratification between the two governments. It was a watershed moment in East Asia’s transition from conflict to peace, and it established a place for the ROC in the international community following the ROC government’s relocation to Taiwan.

For a long time controversial questions about sovereignty over Taiwan have confounded the nation’s people, and consumed much national energy. The issue has huge importance for questions on the status and future of the ROC. To mark the 60th anniversary of the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, the Academia Historica and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs co-sponsored an exhibition and symposium at the Taipei Guest House. This article presents some of the views expressed by the scholars and officials in attendance.

“For a country that was the earliest to be at war with Japan, had fought the longest, and had contributed most to the defeat of Japan, to now be excluded from the peace talks between the Allies and Japan was simply too much to bear!” It was with these words, based on his reading of the recently released diaries of Chiang Kai-shek, that Academia Historica director Lu Fang-shang described the sense of injustice that Chiang experienced in the time leading up to the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco.

In 1951, 48 allied nations including Britain and the US were preparing to sign a peace treaty in San Francisco with the defeated Japan in order to establish Japan’s responsibility for the war and its status in the post-war world. The ROC government had decamped to Taiwan, and was facing many difficulties. In the region, the Korean War was raging, and the Soviet Union and Communist China looked covetously upon Taiwan. Britain, the USSR and many other nations that had already switched diplomatic recognition to Beijing were calling for the Chinese Communists to come to the signing. But the US, which was trying to contain the expansion of communist power following the outbreak of the Korean War, insisted that they should not attend.

Eventually, Britain and the US reached a compromise: Neither mainland China nor the ROC on Taiwan would participate in the peace talks.

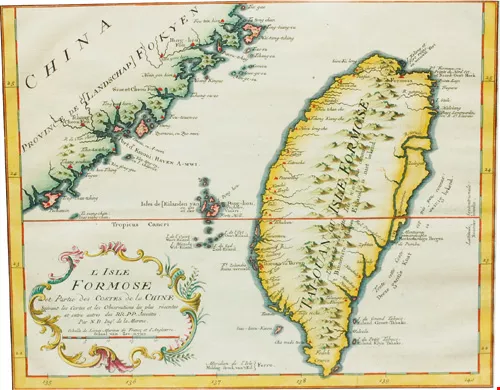

Ancient maps tell the story of Taiwan. On this 18th-century Western one, details of the rarely visited east coast are scant, but in the west of the island many place names are clearly marked.

On June 15, 1951, three months before the peace talks opened in San Francisco, Chiang Kai-shek received news that both the mainland and Taiwan were to be shut out of the talks—and Japan would be allowed to choose the government with which it would sign a peace treaty. Enraged, Chiang viewed the decision as an extraordinary humiliation, describing it in his journal as a “violation of international good faith.” Immediately, he issued a strongly worded statement that stressed that any treaty containing discriminatory articles would not be accepted.

Insisting upon the preconditions of national dignity and international equality, the ROC actively strove to sign a treaty with Japan before the multilateral treaty that had been signed in San Francisco would enter into force. However, there were many points of difference between the ROC and Japan.

In early April of 1952, the talks with Japan hit an impasse, and the ROC asked the US to intervene. The Americans informed Japan that if the US president did not ratify the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Japan would be unable to return to the ranks of sovereign nations. At this, Japan finally relented and sent emissaries to a signing ceremony with the ROC at the Taipei Guest House, which occurred just seven hours and 30 minutes before the Treaty of San Francisco entered into force.

At this critical juncture, Chiang Kai-shek wrote in his diary: “By signing before the San Francisco multilateral treaty takes effect tomorrow, the ROC government will regain some of the standing that it has lost in the international community. After falling for so many years, our nation may have reached a turning point and will start to move in a positive direction.”

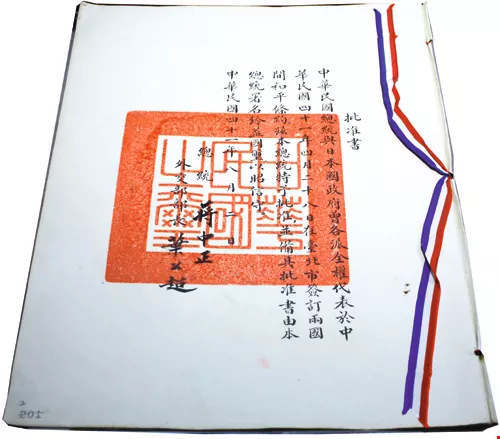

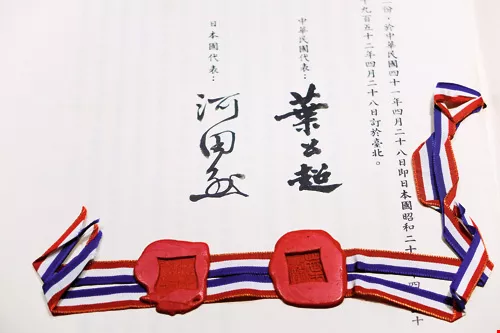

On August 2, 1952, Chiang Kai-shek formally approved the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, which took effect on August 5. The ROC’s instrument of ratification is shown at left.

When the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty was signed and took effect, it formally ended the state of war between the two nations. From a legal standpoint, it also confirmed that Taiwan and its appurtenant islands were being returned to the Republic of China.

Article 2 read: “It is recognized that under Article 2 of the Treaty of Peace which Japan signed at the city of San Francisco on 8 September 1951..., Japan has renounced all right, title, and claim to Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (the Pescadores) as well as the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands.” Article 10 stated: “For the purposes of the present Treaty, nationals of the Republic of China shall be deemed to include all the inhabitants and former inhabitants of Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (the Pescadores).”

Over the past few years, some people have called into question the meaning of Japan’s “renouncing” its claim to Taiwan and Penghu without stating that these were being “returned” to the Republic of China. As a consequence, they have argued that the future of Taiwan was left unsettled. But is there any legal grounding for this argument? It’s worth discussing.

In history, events that relate to sovereignty or transfer of sovereignty over Taiwan include the following:

(1) In 1895, after the Qing Empire lost the First Sino-Japanese War, its representatives signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki with Japan, which ceded the Liaodong Peninsula, Taiwan and Penghu to Japan “in perpetuity.”

(2) In 1943 the leaders of the ROC, the US and the UK issued the Cairo Declaration, which demanded that “all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China.”

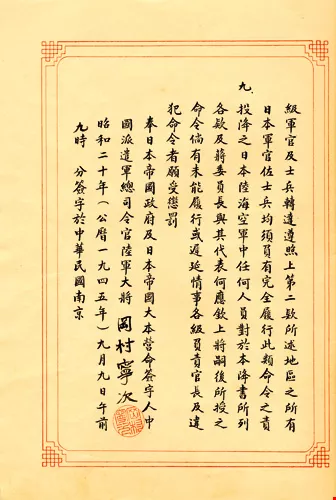

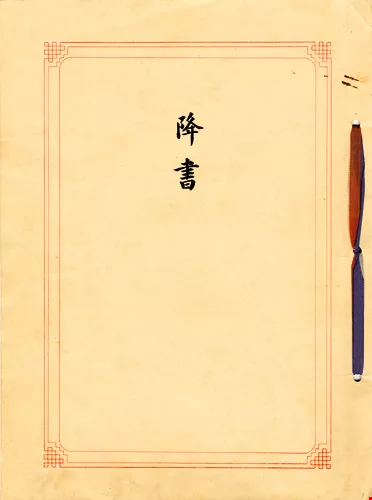

(3) In 1945 the ROC, US and UK issued the Potsdam Declaration. Article 8 states that the terms of the Cairo Declaration must be carried out. On August 14, 1945, the Japanese emperor accepted the Potsdam Declaration. On September 2, aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Japanese representatives signed the Instrument of Surrender, including acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration.

(4) In September 1951 Japan signed the Treaty of San Francisco, and in April 1952 it signed the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty.

National Chengchi University law professor Chen Chun-i pointed out at the symposium that after the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty was concluded, various domestic Japanese legal rulings held that Taiwan was part of the ROC. For instance, in Japan vs. Lai Chin Jung in 1959, the Tokyo High Court ruled: “At the very least it can be determined that from August 5, 1952, after the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty took effect, and as a condition of the treaty, Taiwan and Penghu were returned to the ROC, and the people of Taiwan took on Chinese citizenship under the laws of the ROC. They naturally lost their Japanese citizenship on becoming ROC citizens.”

On August 2, 1952, Chiang Kai-shek formally approved the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, which took effect on August 5. The ROC’s instrument of ratification is shown at left.

The issues of identity have caused much turmoil among the nation’s people for half a century. New understanding about these issues was included in the nation’s senior-high-school history books in September.

Lin Man-houng, former Academia Historica director and now a research fellow at Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History, explained that there were two distinct periods in how textbooks in Taiwan discussed the return of sovereignty over Taiwan: From 1957 to 2006 they described the Cairo Declaration as having established that sovereignty over Taiwan belonged to the ROC. However, Lin pointed out, in fact it was the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, not the Cairo Declaration, that superseded the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Then the history textbooks in use from 2006 to 2011 made the case that as the ROC was not a signatory to the Treaty of San Francisco, although Japan had indeed renounced its sovereignty over Taiwan, no other nation had been designated to assume that sovereignty. On this basis it was argued that the island’s future should be left to its people to decide.

Lin Man-houng pointed out that Article 2 of the Treaty of San Francisco required Japan to “renounce all right, title and claim” to Korea, Taiwan, the Pescadores (Penghu), the Kurile Islands, Antarctica, and the Spratly Islands. Article 4, on the other hand, required Japan to make “special arrangements” with the “authorities presently administering” the areas mentioned in Article 2.

“Article 26 requires detailed reading,” said Lin. “In it Japan declares its preparedness to sign a bilateral peace treaty with any nation that it had fought against that was not a signatory to the Treaty of San Francisco and that adhered to the spirit of the United Nations, on substantially the same terms as in the Treaty of San Francisco. That article laid the groundwork for a separate bilateral treaty to be concluded between Japan and the ROC. That treaty—the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty—gave legal embodiment to the Cairo Declaration.”

There are people who argue that when Japan established diplomatic relations with the PRC, Japanese prime minister Masayoshi Ohira repudiated the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty in a press conference. But Lin pointed out that just as the Cairo Declaration could not override the Treaty of Shimonoseki, once the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty was signed, only the ROC had the authority to deal with the issue of Taiwan’s sovereignty. Consequently, the 1978 Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Japan and the PRC could not bring about any further transfer of sovereignty over Taiwan.

“International treaty provisions include those currently being implemented, and those whose implementation is already complete. Those that are in progress can be terminated, but those already completed cannot.” Thus after the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty took effect, only the ROC had the right to make any further disposition regarding sovereignty over Taiwan. Assertions that Taiwan’s status was left undetermined had no basis in law, said Lin.

Nanjing, September 1945: ROC Army commander-in-chief Ho Ying-chin accepts Japan’s Instrument of Surrender, signed by Japanese expeditionary force commander Yasuji Okamura.

Today, the purpose of taking another look at the meaning of the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty with strict attention to legal principles is to understand the inextricable ties that bind Taiwan to the Republic of China and to provide the ROC with a wider international space in which to maneuver.

Addressing the symposium, Minister of Foreign Affairs Timothy Chin-tien Yang stated that the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty had laid the foundations for 60 years of friendly relations between the two nations. A recent public opinion survey in Japan had revealed that as many as 91% of Japanese believed that Japanese relations with Taiwan were good, 67% felt close to Taiwan, and 84% believed Taiwan was trustworthy. And in Taiwan the destination to which the greatest numbers of people would like to travel was Japan. These attitudes reflected the deep sense of friendship between the two nations’ peoples.

President Ma Ying-jeou, in his address, noted that in the last four years the ROC government established a representative office in Sapporo and signed the first ROC-Japan investment agreement in 60 years, to spur economic development. Japan’s National Diet also passed a bill governing the display of foreign art works, allaying concerns about what could happen to works exhibited there from the National Palace Museum collection. And after last year’s devastating earthquake and tsunami in northeastern Japan, the Taiwanese public contributed unstintingly to relief funds, donating a total of NT$6.6 billion (about ¥20 billion)—more than the other 93 contributing nations combined. Consequently, the two sides specially issued a “Declaration of Deep Friendship.” Ties between the two nations would only grow stronger in the future.

The vastly different opinions on the history of shifting sovereignty over Taiwan have been in part related to the different memories that ethnic groups in Taiwan have about Japanese rule and the Sino-Japanese War. Let us hope that with dialogue and an objective view of history, the next generation will have a clearer understanding about these issues of national identity.

After representatives from the ROC and Japan signed the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, they posed for photographs at the Taipei Guest House. Relations have remained friendly in the more than half a century that has passed since.

In April of 1952 ROC Minister of Foreign Affairs Yeh Kung-chao and Isao Kawada, representing the Japanese government, signed the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, formally ending hostilities between the two nations.

Nanjing, September 1945: ROC Army commander-in-chief Ho Ying-chin accepts Japan’s Instrument of Surrender, signed by Japanese expeditionary force commander Yasuji Okamura.

In April of 1952 ROC Minister of Foreign Affairs Yeh Kung-chao and Isao Kawada, representing the Japanese government, signed the ROC-Japan Peace Treaty, formally ending hostilities between the two nations.