No Regrets: Author Lucy Chen Reflects on an Extraordinary Life

Su Hui-chao / photos courtesy of Lucy Chen / tr. by Josh Aguiar

January 2011

Author Lucy Chen's keen eye has witnessed social upheaval on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. During the February 28 Incident of 1947, she saw her teacher taken away never to return. Her and her husband's idealism prompted them to leave the staunchly anti-communist atmosphere of Taiwan to support the socialist revolution in mainland China, where they encountered the nightmare of the Cultural Revolution.

Now just past 70, the age at which Confucius famously said he learned to follow his heart's desires, Chen has published a brave autobiography that shows her pen has lost none of its former incisiveness.

On November 15, 2010, Lucy Chen's birthday, the Hong Kong Literary Reportage Association held its inaugural international conference on Chinese-language literary reportage. Lucy Chen (Chinese name Chen Ruoxi, also transliterated as Chen Jo-hsi) was one of several experts invited to attend, and she presented a brief paper inspired by her short story "Jingjing's Birthday."

"Is my work even literary reportage?" was the question lingering in her mind as she initially considered whether or not to attend the event. She had never set out to write anything in the genre, and was not particularly interested in presenting. After publishing a Buddhist work, Hui-xin-lian, in 2000, she vowed to give up writing entirely. Her autobiography, No Regrets, published in 2008, seemed to suggest that she was prepared to hang up her quill for good, though she has since written an article on the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo.

Her apartment on Chaozhou St. may not be a palace, but it's a comfortable place for her to read, write, and relax. It is also a space where Lucy Chen can feel the presence of young Chen Xiumei, her former self, who once declared her intention to live life alone.

"Writing belongs to my past. Now I'm more concerned with living," laughs Chen, who rents an old apartment on Chaozhou Street in Taipei. The edifice that is her life is built on a foundation of words, beam after literary beam whose weight has lessened over time, leaving behind only laughter.

While contemplating whether to attend the conference, she reread her short story "Jingjing's Birthday," which was originally published in Hong Kong's Ming Pao newspaper in 1976.

Reexamining her work in detail made her realize that, with the exception of the conclusion, it was unquestionably a work of literary reportage, "because all of the details of the story are taken from actual occurrence."

Chen's works are like excavators drilling away inexorably at hidden veins of truth. Life is an amazing intersection of fate and chance. At 18, Chen aspired to the journalistic profession because she wanted to "illuminate truth and expose the dark underbelly of society." But her dreams to study journalism at the university level were derailed by circumstance. Conveniently located National Taiwan University had no journalism department, but National Chengchi University, which did, was too far away to commute, and the family couldn't afford to pay for accommodations close to campus. In the end, NTU was the only viable alternative. When the entrance exam test results were promulgated, she had earned a berth in NTU's Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures. Even still, she was hard pressed to find someone to loan her tuition money, though later she was able to achieve financial independence by tutoring and through the publication of her stories.

Concerned about the long-term health of Taiwan's ecosystems, in 1996 Chen took to the streets to protest the construction of a fourth nuclear power plant.

Lucy Chen was born on November 15, 1938. Her official birth-certificate name was Chen Zhuzi, but it was eventually changed. When she was in third grade at Xin'an Elementary, not long after her family had moved to Yong-kang St. in Taipei, the government initiated a program designed to eradicate any lingering traces of Japanese cultural influence in Taiwan. Schools forced girls whose names bore the Chinese character "zi" (pronounced ko in Japanese), which means "child" and is frequently encountered in Japanese girls' names, to find more suitably Chinese-sounding replacements. Chen herself decided on her new name: Chen Xiumei.

Chen's rebirth as Chen Ruoxi took place during her years at NTU. Little did she realize then that that name would someday be shrouded in controversy after she defected to the communist mainland, or that her story "The Execution of Mayor Yin" would shock Chinese readers the world over.

She chose the name Chen Ruoxi because of its gender neutrality, and because she wanted to challenge stereotypes and become a voice for women.

She was born into a working-class family. Her father was a carpenter who was only semi-literate. Her mother was taken in by the Chen family before she was three years old as an intended future bride. Her mother's life read like a classic folktale of a young maid enduring hardship and abuse at the hands of a severe future mother-in-law. Having endured the toil of growing up amongst a family not her own, she adamantly refused to see her daughter raised by a landlord family. Chen's father was open-minded about his children's education, figuring that they should be allowed to go as far as their test scores took them. After elementary school, her brother, the oldest son, went off to work at the Taiyang Mining Company. Chen's academic brilliance, on the other hand, could not be denied, as she conquered each challenge on her ascent from Taipei First Girls' Junior High School through Taipei First Girls' High School all the way to NTU.

Chen's time at NTU was a period of great intellectual ferment. She and her classmates' nurturing of one another fostered a lively and creative academic culture. In this picture from 1962 we see Chen (right), Ouyang Zi (second from right), and Yang Meihui (third from right) at the Fu Garden on the NTU campus.

The massacre of February 28, 1947 took place when she was nine years old. Like the majority of Taiwanese, the lesson that her father drew from the tragedy was "stay away from political affairs," and this was exactly how he admonished his children. Steering clear of all things political, young Chen spent hours at the stores that rented books, squatting on the ground as she devoured comics and serial novels. After finishing junior high school she became infatuated with martial-arts epics and literary novels. She read through all the famous works of Western literature at the library and began submitting her own stories for publication to earn some spending money. At that time there was a girl in her class, Chen Zhe, who was an avid reader of novels, and they soon became fast friends. When Chen Zhe created a scandal by having an affair with a teacher, Lucy Chen courageously went to her friend's house to plead her friend's case. Chen Zhe later achieved household name status as a romance novelist writing under the nom de plume Qiong Yao.

Lucy Chen's class in foreign languages and literature at NTU was an amazing concentration of talent the likes of which had neither occurred before that time nor has since. Many of that year's graduates went on to enjoy distinguished literary careers, such as Bai Xianyong, Wang Wen-xing, Li Ou-fan, Guo Song-fen, and Hong Zhi-hui (Ou-yang Zi). During that time, the Literary Review edited by Hsia Chi-an was widely recognized as the preeminent belles-lettres periodical. One of Chen's stories, "Weekend," originally written as a school assignment, was published in the Review thanks to the endorsement of her instructor, Ye Qingbing. After that taste of success, Chen redoubled her efforts, producing "Uncle Qinzhi." "The reason was that the money for one story was equal to a whole semester of tutoring tuition."

Though faded with age, this photograph contains a wealth of sentimental value. In it, the young Lucy Chen (right) in a white top and black skirt, poses with her classmate Ouyang Zi (left) and two sisters of Ouyang's on the campus of the Taipei First Girls' Junior High School. Chen and Ouyang travelled a long road together that began in junior high school and concluded at NTU.

When word got out that Hsia Chi-an was planning to leave Taiwan, Bai Xianyong proposed founding a new magazine in the mold of the old Literary Review, but with an increased emphasis on contemporary writing, ergo the name Modern Literature. The new periodical honored the legacy set in motion by the old, but further used literature as the vehicle to expose modern strains of thought evolving in the US and Europe to a readership living in a tightly controlled authoritarian society. For Chen personally, the magazine furnished an arena in which she could give play to her more experimental impulses, notably her existential story "Balinese Journey."

That particular story was a watershed in her evolution as a writer.

Some writers write only for themselves and place little importance on how well their audience understands their work. Chen knows clearly that she doesn't fit this type at all, and writing "Balinese Journey" was the experience that provided the enlightenment. She had never intended to write anything overly opaque, so when she learned of how her readers struggled with this particular work, she gladly put modernistic technique behind her to return to the familiar sights, scenes, and humble characters of her childhood in her subsequent works, "Spirit Calling" and "Xinzhuang."

"Xinzhuang" is the tale of an unfaithful wife. French professor Li Lie-wen was so taken by the story that he insisted that his student Hong Zhi-hui pass on his best wishes to the author.

The great Lu Xun said that literature is about life, and that prose is the knife that slices at the status quo in order to expose the dark face of society. As a young woman, Chen's waifish exterior concealed a formidable spirit, uncompromising and blessed with tremendous strength of purpose. She worshipped Lu Xun. Personality determines a writer's style; it also shaped her future decisions.

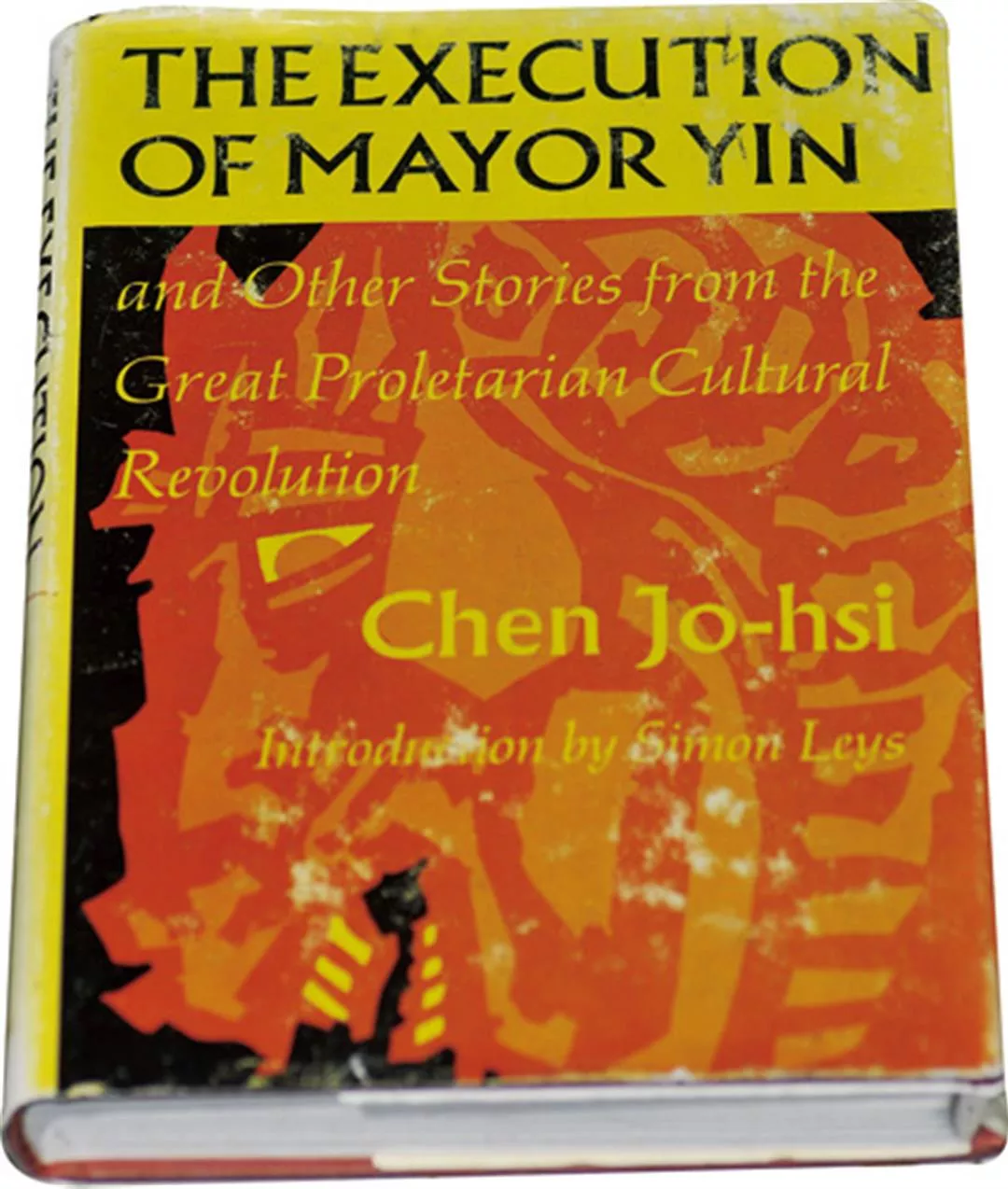

The Execution of Mayor Yin was released in English translation in the US.

Literary critic Ye Weilian has divided Chen's literary output into two periods, the first being 1958-1962, during which she published in Literary Review and Modern Literature, and the second beginning 11 years later when she published the spine-tingling Mayor Yin stories.

Ye believes that no other short story writer's work can be sifted so definitively into completely contrasting stylistic periods. The early works are "emotionally charged, the language given to hyperbole, with an emphasis on excitement. The progression of plot shows the influence of unrestrained subjectivity and sporadic volatility churning up from the author's id." Eleven years later, however, Chen's style had undergone complete transformation: "Every word is welded to a concrete, objective reality, much like a work of journalism-all traces of subjectivity have vanished. In the whole of Chinese modern literature, no other body of individual work has undergone such a remarkable sea change."

In other words, Chen's second period reveals the work of an objective observer using the short story form to capture reality. What life experiences, what kind of psychological transformation, could induce such a seismic shift in style?

The story is rather involved. After graduation, Chen headed off to Johns Hopkins University in the US for further study, during which time she drew inspiration from reading Hemingway, Faulkner, Steinbeck and other American authors.

She never intended to stay in the US; her plan had always been to return to Taiwan immediately after obtaining her master's degree. But after meeting PhD kinesiology student Duan Shi-yao, she felt a new set of priorities take hold.

The Execution of Mayor Yin, republished by Chiu Ko in 2000, is a shining example of Chen's "literature that expresses life" credo. The stories in the collection provide snapshots of life during the Cultural Revolution and of the futility experienced by ordinary people laboring under a short-circuited political system.

For the most part, Chen is a collected individual not given to compulsion, but a streak of idealism lights her core. Idealists are often attracted to the egalitarian message of socialism, and this was true of both Chen and Duan. United by their love and shared ideals, the couple married and delved deeper into the works of Marx, Lenin, and Mao. Their devotion grew to the point that they were ready to make a monumental leap of faith, and on October 16, 1966, as the flames of the Cultural Revolution burned deadly white, the couple departed for China.

Prior to their "return" to China, they had heard the stories of writer Lao She humiliated by Red Guards to the point of drowning himself in a lake, but they were certain that some misunderstanding had played a role in the tragedy. And when customs confiscated five books of paintings, their stamp collection, and travel slides, they were prepared to accept that those articles were symbols of a decadent bourgeois existence they were prepared to leave behind in order to recreate themselves.

Seven years later, due in part to the Diaoyutai Islands protests but mostly because she "didn't want her children to hate her," Chen, her husband, and the two children born to them under the red flag left China, settling at first in Hong Kong before relocating to Canada and ultimately the US. While making their escape they experienced enough danger to pack any decent thriller.

In Hong Kong, she felt lonely and confused. The future was clouded with uncertainty. It had been 11 years since she had last written anything-"I was sure that I would never write again in this lifetime." But the experiences of the Cultural Revolution that weighed so heavily on her heart reanimated her pen, and the collection of stories highlighted by "The Execution of Mayor Yin" and "Jingjing's Birthday" spilled forth one after the other.

So many of her friends in China had suffered injustices that they couldn't talk about, grievances that they buried within them. Chen made it her job to speak on their behalf. Real life situations and experiences provided the material; all that was needed was to supply the characters and expand upon the plot in a logical way. "From there, it's up to the reader to contemplate," she says. The Execution of Mayor Yin fully bears out Chen's realistic credo of "literature that expresses life." Her subsequent long works Return, Breaking Out, Paper Wedding, and Hui-xin-lian all reflect this aesthetic.

In 2008, at age 70, Lucy Chen published her autobiography, No Regrets.

Reflecting back on a period of her life that has since become the stuff of legend, Chen says: "In the seven years that I spent in the mainland, I don't think I accomplished a single thing. As a farmer, I wasn't even cultivating enough to feed myself; as a teacher-well, what could I accomplish in that environment? Looking back I can say that the only substantial gain was a deeper understanding of my countrymen. I used to take being Chinese for granted, an unchosen fact of my birth. But those years revealed to me the tragic- stoicism of the Chinese people, their charm and their dig-nity-qualities that no government, no matter how authoritarian, could ever eradicate."

Back in the capitalist world, Chen lived in Canada for five years, earning hourly wages packing gramophone records and then working as a bank teller. She later relocated to San Francisco with her husband. Her open, inclusive nature made their home in Berkeley a magnet for men and women of letters from throughout the Chinese-speaking world, a kind of hostel for intellectuals.

In the meanwhile, the stories set in the Cultural Revolution had swept Hong Kong and Taiwan like a tornado. Moreover, The Execution of Mayor Yin had been released in Japanese and English translations, making Chen a darling of the literary world. Time Magazine and The New York Times both ran reviews of the stories, and in their wake came invitations to lecture at major universities throughout the United States. The exposure also raised the international profile of contemporary Taiwanese literature.

Though she had made her home in so many places, Taiwan was still the place that mattered most.

After the Formosa Incident of 1980, Chen returned to Taiwan with a petition signed by 27 overseas Taiwanese authors and scholars to present to President Chiang Ching-kuo. After an intensive effort, the president finally issued a sympathetic statement: "If even one person is wronged, then my heart will not be at ease."

On the plane back to the US, Chen's head was a web of tangled emotions. She reflected that in those 18 years away Taiwan had changed so much. So had her family. Everything in Taiwan seemed to be a world apart, and she was stricken with a feeling of shame that hadn't done anything to help her native land.

Feeling that she owed an unpaid debt to her country, she was eager to make amends. She figured the best way to fulfill her obligation was to work in Taiwan. At this juncture, the owner of the Taiwan Times, Wu Jifu, came to San Francisco to launch the Far East Times, and he asked Chen if she would be interested in taking the helm of the op-ed section. Chen gave him an unequivocal yes, but she soon found that many took umbrage at her unfettered candor. The daily strain of balancing her ideals with practical realities had become unbearable, but, as it turned out, the periodical went under after just 19 months, and she found herself once again contemplating a future home in Taiwan.

"Writing belongs to my past-now I'm more concerned with living." As she revisits the long and lonely corridor of NTU's College of Liberal Arts, she is overtaken by the slipping away of time, her usual laughter giving way to quiet reflection.

Her yearning for home was a constant obsession.

August, 1995 was a time of great uncertainty in Taiwan. While record numbers of Taiwanese were intimidated into emigration by PRC saber-rattling, Chen finally made her long-awaited return home. Back in Taiwan, she busied herself with teaching, writing, travel, and lecturing. She held posts as "author in residence" at various universities, visited temples and was active in the movement to modernize Buddhism and give it a uniquely Taiwanese face. She was involved in associations for women writers and senior citizens' clubs, as well as participating in conservationist efforts. Her life was eminently satisfying except for the fact that her husband, Duan Shi-yao, continually clamored for her to return to the US. Ultimately, she had to choose between Taiwan and her family, so she did what many would find heartless: she severed her ties with her family to remain in Taiwan. With her attorney son acting as witness, she finalized her divorce with her husband.

Life defies expectation. Here at the dusk of her life, Lucy Chen found herself once again face to face with Chen Xiu-mei, the young woman who once declared her intention to live alone.

The apartment on Chaozhou St. is big enough for a sole occupant. Though a bit spartan in its amenities and lacking in any conspicuous decorations, she finds it perfect for the simple life she wishes to lead.

In this same apartment she wrote her autobiography, No Regrets, which, despite having 50,000 characters worth of "controversial" content excised by the publishers from the original 230,000 characters, still attracted an enthusiastic readership on account of its unpretentious style. She has heard that Wang Wen-xing, her old classmate, was not amused by the descriptions of the amorous liaisons of his youth, and for this she feels some regret.

She is most deeply gratified to know, however, that readers on both sides of the Taiwan Strait have found her book to be thor-oughly riveting and indispensible.

She scours the paper every day for newspaper clippings that interest her, and is most concerned with gender issues. She'll read Qinqiang by mainland author Jia Ping'ao, complaining all the while that the writing is cheap. She's been distancing herself from the metaphysical preoccupations of Buddhism in favor of the vibrant social camaraderie of Christianity that injects light into her mundane existence. She's "adopted" a dolphin, campaigns for wilderness conservation. She's opposed to the Su'ao-Hua-lien Highway project, and finds the anti-mainland vitriol so common amongst Taiwanese today to be quite alarming.

"Life first and foremost" is the mantra of the 72-year-old Lucy Chen. She's long ceased to be the Chen Ruoxi who penned The Execution of Mayor Yin all those years ago-many times she forgets she's ever been a writer. Her focus today is simply to live well, laugh often, and enjoy the freedom of her silver-haired golden years.

This is the 2010 Hong Kong edition of the novel Huixinlian.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)