A dolphin smiles impishly as it frol- ics near our boat. Like some sort of sea sprite, it beckons us away to its enchanted waterworld....

The dolphin-viewing boat rides operated off Taiwan's east coast are an unforgettable pleasure, but a trip to see the dolphins off our west coast shows a tragically contrasting picture.

The population of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) living along Taiwan's west coast has dropped below 100 due to over-development along the coast that has diminished their habitat and food sources, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified these dolphins as critically endangered (CR), one step away from extinction in the IUCN classification scheme.

To make matters worse, Kuokuang Petrochemical Technology Co. is making plans to invest NT$400 billion in a complex to be built on a 2,800-hectare land reclamation project along the coast in the Changhua County townships of Dacheng and Fangyuan. These coastal waters are a passageway for the endangered humpback dolphins, which live and feed there as they move along a north-south path parallel to the coast. Industrial developers pledge to protect the humpback dolphins and minimize harm, but environmental groups, concerned over the ever-shrinking habitat of the dolphins, have launched an "environmental trust" to solicit participation in a project to buy up the Changhua County coastal wetlands. Calls to save this important habitat are growing.

How are the humpback dolphins doing today? A government pushing hard for economic development finds itself in a tug-of-war with private citizens and international wildlife conservation groups concerned about the dolphins. How do we strike a proper balance between the welfare of the dolphins and of the environment, on the one hand, and the future of Taiwan, on the other?

The streets of Taipei on June 9 bake under a glaring sun. Meanwhile, on the fourth floor of the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA), simmering passions threaten to set the conference room aboil. A meeting of experts has been called to assess how plans by Kuokuang Petrochemical to build a coastal plant are likely to affect a population of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins there, and how to best deal with the matter.

Before the experts start discussions, the public has a chance to speak. Representatives of the fishing industry are furious that overprotection of the dolphins leaves fishermen with nothing to catch, while local residents complain that blocking the plans of Kuokuang Petrochemical would prevent the firm from providing tens of thousands of jobs and make it impossible for the moribund rural economy to spring back to life. Environmental groups, on the other hand, warn that habitat destruction will doom the humpback dolphins of Taiwan's west coast to extinction.

Ironically, it is only in the last year or two that most people in Taiwan even became aware that there were "pink dolphins" (i.e. humpback dolphins) off Taiwan's coast, and scientists only began studying them seven or eight years ago, in sharp contrast to the situation with the bottlenose dolphins and spotted dolphins off Taiwan's east coast. Yet just as we are starting to know and study these peculiar-looking humpbacks that may well be an independent population unique to Taiwan, it appears that they may be on the verge of extinction.

Professor Chou Lien-siang of National Taiwan University's Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, has studied cetaceans for 20 years and is known affectionately as "dolphin mama." According to Chou, there are currently around 6,000 Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins worldwide, found in shallow coastal waters off China (south of the Yangtze River), the Indian Subcontinent, and East Africa. They do not usually venture into water any deeper than 20 meters.

Chou first learned of humpback dolphins off the coast when she surveyed fishing villages 20 years ago. In the course of the survey she ran across records of humpback dolphin strandings. It wasn't possible to study them systematically in the past due to the huge expense of studying them at sea, which is five times more costly than studying animals that live on land. A lack of sufficient funds at the Council of Agriculture posed an obstacle to study of these dolphins, which meander constantly up and down the west coast, seldom staying long in any one place.

The first seaborne survey of the humpback dolphins in Taiwan was carried out in 2002, though the impetus for the research was not local. Scholars studying the humpback dolphins in Hong Kong were wanting to know more about the ones on this side of the Taiwan Strait, and so funded research by Dr. John Y. Wang, a Chinese-Canadian cetacean specialist who works in Taiwan and is the co-founder of the Formosa Cetus Research and Conservation Group. Wang found small populations of humpbacks off Miaoli, Taichung, and Changhua. Environmental groups in Taiwan subsequently raised money to support further research that produced a population estimate of only 99 humpback dolphins. Activists responded by establishing the Matsu's Fish Conservation Union ("Matsu's fish" is what fishermen in Kinmen and Xiamen call humpback dolphins). This group began training volunteers and sought to raise public awareness of the dolphins' plight.

Throughout this same time period, the government was moving forward with plans for several major economic development projects all concentrated near important habitats of the humpback dolphins, including a thermal power plant in Changhua, Kuokuang Petrochemical's eighth naphtha cracker (with financial backing from China Petroleum Corporation), Phases 3 and 4 of the Central Taiwan Science Park, and the Dadu Weir Project (Fig. 2). Environmental groups frequently have attended environmental impact assessment meetings at the EPA to argue their case and stage protests. Their activities have caught the government's attention, and the Council of Agriculture has budgeted funds for expanded research by a team led by Chou Lien-siang. She won additional funding from the Taiwan Power Company (Taipower) and Kuokuang Petrochemical for further surveying that finally yielded a relatively thorough understanding of the humpback dolphins' ecology.

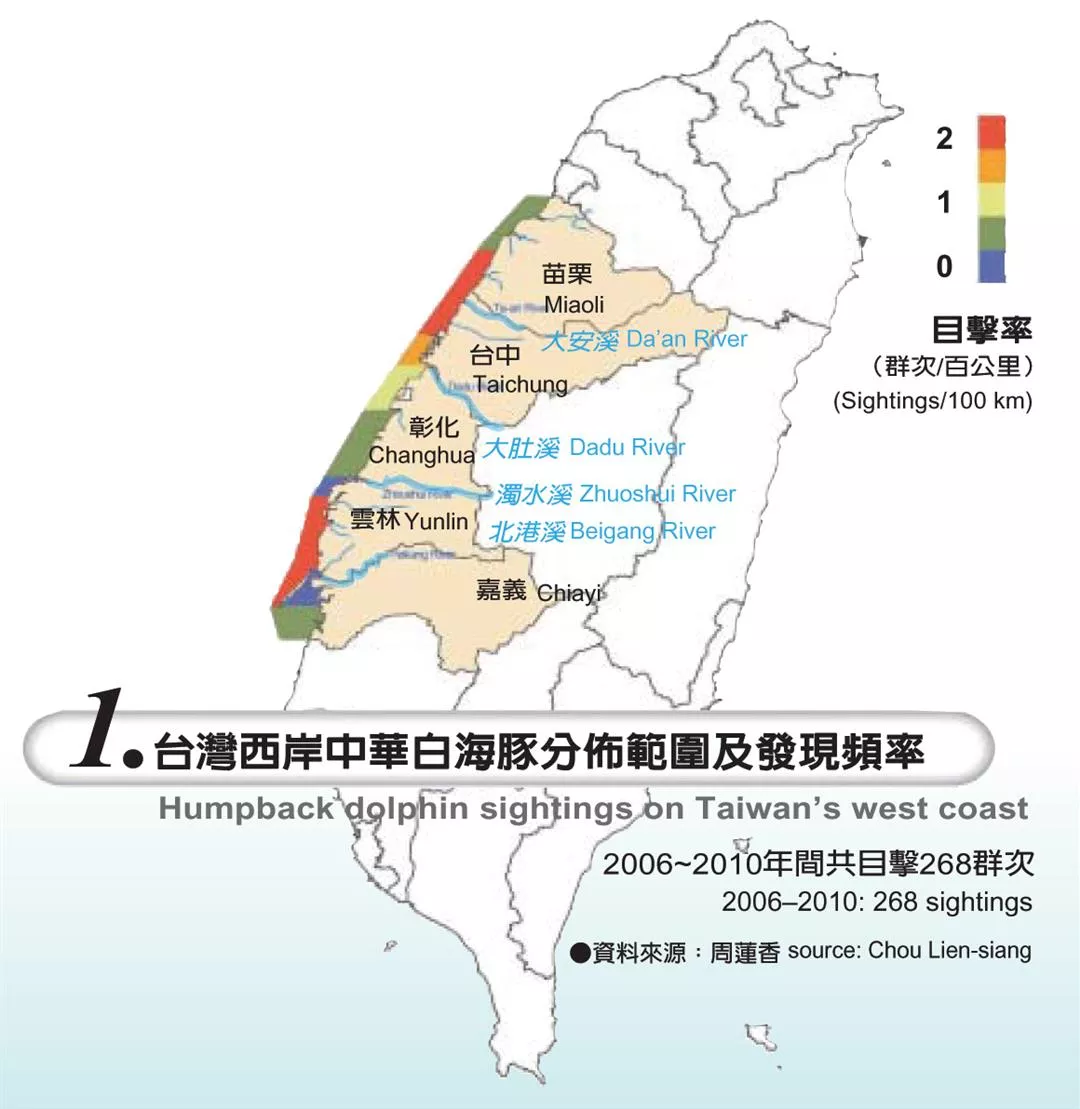

Humpback dolphin sightings on Taiwan's west coast

Most dolphins are either gray or black in color, but as the Indo-Pacific humpback matures it turns either white or pink, with dark speckles, and features a camel-like hump under its dorsal fin. Its unique appearance sets it apart from all other types of dolphins.

After four years of surveying, Chou has found that Taiwan's humpback dolphins range from the Miaoli County fishing port of Longfeng in the north to Tainan County's Jiangjun fishing port in the south, and spend their time in water averaging 7.6 meters deep and three kilometers from shore. Their range is thus a narrow band extending some 200 kilometers from north to south, including two main "hotspots" for hunting and social activity. One hotspot extends from southern Miaoli to northern Changhua, while the other runs from Yunlin to the Waisanding barrier island at the border of Yunlin and Chiayi counties (Fig 1).

Says Chou, "We've conducted 70 surveys per year in recent years and taken a total of over 40,000 photos, which we use to identify individual dolphins. On that basis, we estimate a population of 84 to 86 humpback dolphins on the west coast."

Chou explains that the standard international practice in surveying small dolphin populations is to take a photo whenever one is spotted and note the place and time of the sighting and the dolphin's behavior at the time. The photos are then used to identify individuals and analyze how they behave in different areas.

Having compared the overall sighting rate for Taiwan's humpback dolphins (three populations per 100 kilometers) and the sighting rate along the Changhua coast (0.46 populations per 100 kilometers), and based on analysis of Changhua coastal behavior records, Chou has concluded that the humpback dolphins off the Changhua coast are mostly just passing through. In the waters near the proposed Kuokuang Petrochemical complex, she has only once spotted a dolphin feeding.

"Our last two years of surveys indicate that most of the dolphins stay generally put in one of two 'hotspots,' one north and one south, while only about 30% of them, or some 25 dolphins, roam north and south. Southern Changhua is an important passageway for them."

Tsai Chia-yang, director of Changhua Coast Conservation Action and a long-term observer of the Changhua coastal ecology, is less than sold on the idea that dolphins are mere passersby off the southern part of the Changhua coast (site of the proposed Kuokuang Petrochemical complex). Tsai points out that the intertidal zone is fully six kilometers wide at this part of the coast, and it is quite possible that humpback dolphins may take advantage of the tides to herd fish into the shallows and feed on them, which wouldn't be observable to someone on a boat six or seven kilometers away. Moreover, the mouth of the Zhuoshui River is rich in nutrient salts, and ought by all rights to be an ideal feeding ground for the humpback dolphins. Further study is needed to determine whether humpback dolphins feed and live at the mouth of the Zhuoshui River.

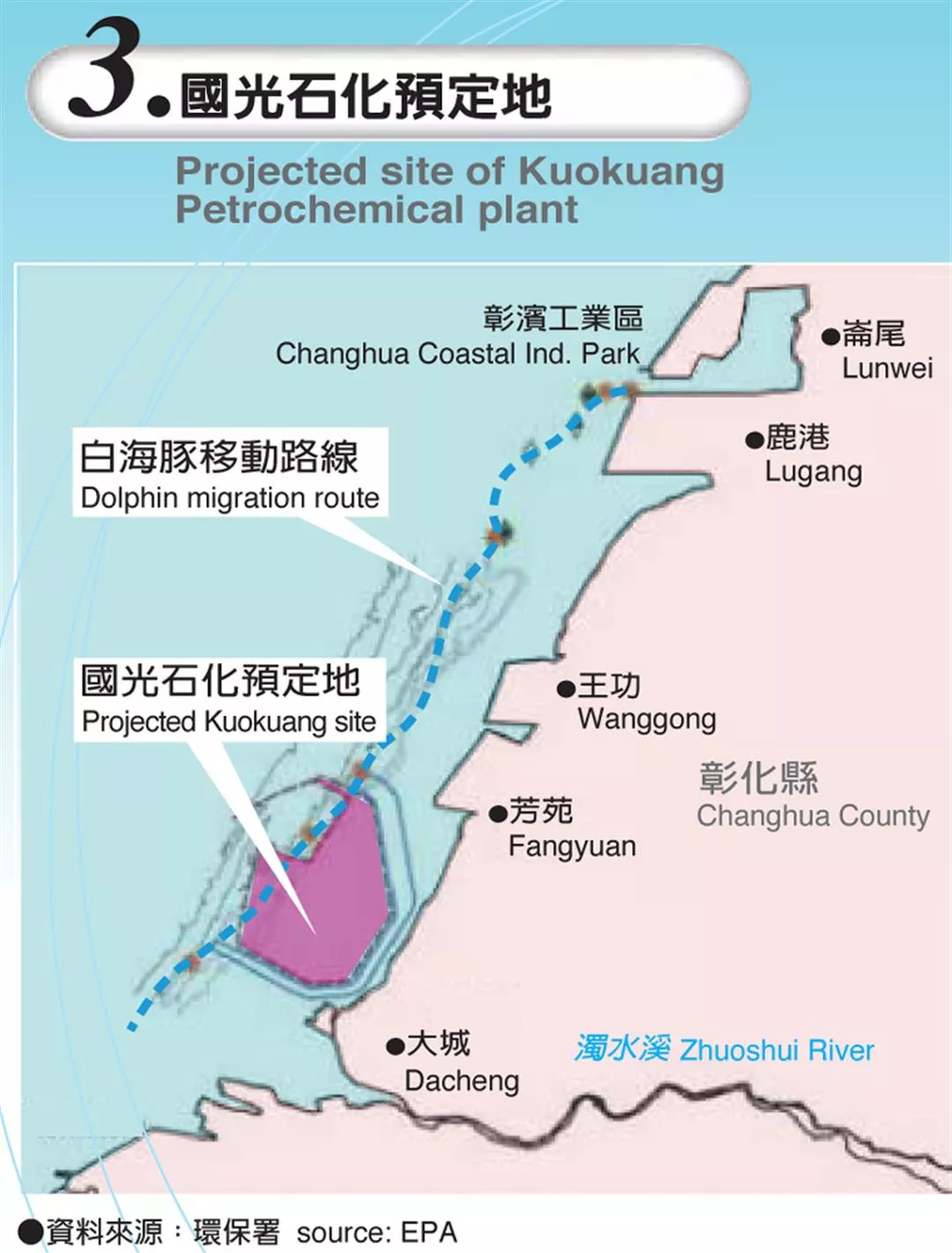

Projected site of Kuokuang Petrochemical plant

Even leaving aside the question of whether the humpback dolphins live and feed in the area selected for the Kuokuang Petrochemical complex, another question remains: the path followed by dolphins in their north-south movements cuts right through the western edge of the proposed site of the Kuokuang complex (Fig. 3). If the huge industrial complex sitting in the path of the humpback dolphins' north-south passageway cuts the population in two, will it hasten their extinction?

A key to answering this question has been provided by Huang Xianglin, a post-doctoral fellow in Chou Lien-siang's research team, who used a dynamic simulation method and plugged in such variables as lifespans, reproduction rates, pollution, and natural motion to calculate the likelihood of extinction. Assuming permanent splitting of the population, his findings indicated that extinction would occur within 13 to 75 years, while a temporary split might cause the population to fall by 6-50% after 15 years. He therefore recommended that the population not be split apart for any more than seven years.

The Kuokuang Petrochemical project has not yet passed its environmental impact assessment, but phase one of the proposed project is expected to take four years to complete. After that, market conditions would determine whether there would be a second phase. One thing we do know for certain is that the work on several thousand hectares of land reclamation would severely disrupt the seafloor ecology, thus exacerbating feeding difficulties for the dolphins, whose food sources are already on the decline. And the building of an industrial harbor would also be very stressful for noise-sensitive dolphins, which rely on sonar for locating themselves and communicating. Would they be able to stand the 24/7 rumbling and clanking during piledriving operations and the digging of a shipping channel? It is difficult to be optimistic.

Professor Chen Chi-fang of the Department of Engineering Science and Ocean Engineering at National Taiwan University feels that noise generated by piledriving during construction of an industrial harbor could damage the hearing of dolphins within the immediate area, and noise from vessels entering and leaving the harbor once it was in operation would probably shorten the radius within which the humpback dolphins can communicate by sonar, thus forcing them to expend more energy in searching for food or their companions. Hence it would be necessary to take underwater sound recordings during construction and do long-term tracking of the presence of dolphins. She suggests suspending work or temporarily halting entry and exit of ships to and from the harbor if noise were to reach excessive levels, or whenever a dolphin showed up within the area affected by the noise.

Taiwan's humpback dolphins live three kilometers offshore in an area along the west coast that bristles with factory smokestacks. Shown here along the coast are four massive smokestacks at the Taichung thermal power plant. Located right nearby are Dragon Steel Corporation, the industrial parks of Taichung Harbor, and a petrochemicals industrial park.

Even supposing the humpback dolphins could put up with the underwater noise, an even more nettlesome problem would be their ability to navigate the deep waters into which they would be forced after completion of the project. Once a shipping channel has been dug, dolphins much better accustomed to waters ranging from 10 to 20 meters in depth would suddenly have a daunting new depth to negotiate.

Tsao Mihn, the president of Kuokuang Petrochemical, is confident that water depth would not be a problem. He points to studies indicating that the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins can swim in waters up to 32 meters deep, and notes that the humpback dolphins have no problem getting past the 28.5-meter waters off the tip of the jetty at Taichung Harbor (to the north of the Kuokuang Petrochemical project) or the 24-meter depths off the jetty at Mailiao Harbor (to the south). How would the planned 17-meter depth off the jetty at the Kuokuang industrial harbor, asks Tsao, be a barrier to the humpback dolphins?

Chou Lien-siang readily concedes that the Kuokuang industrial harbor would not completely cut off the north-south movement of the dolphins, but warns that the 17-meter waters off the jetty and the 27-meter shipping channel would approach the dolphins' limit, and the added interference of ship traffic would force humpback dolphins to expend more energy to get through this area.

The mudflats between the mouths of the Zhuoshui and Erlin Rivers are the last natural seacoast in Taiwan, and an important habitat for crabs, migratory birds. Now they may very well be filled in to make an industrial park.

To mitigate the impact of the petrochemical complex and the industrial harbor, Chou has proposed behavioral training for the dolphins, using food to induce them to follow a desired path along the Changhua coast. "This is the only thing I can think of in the event they really do go ahead with the Kuokuang Petrochemical project."

Chou explains that the behavioral training would entail a boat traveling through a hotspot most frequented by the dolphins, all the while emitting special underwater sounds and throwing off bait fish to attract the dolphins' attention and get them accustomed to approaching whenever they hear the boat's special sounds. The research team already knows quite a bit about the movements of individual dolphins, so once they've determined that all the dolphins are reacting to this "friend-of-the-dolphins" boat, they would then steer the boat into gradually deeper waters along the Changhua coast, thereby inducing them to complete the north-south passage.

If this method didn't work, the next step would be to set out fish cages on either side of an 800-meter-wide area where the water is deepest. Bait would first be placed inside the cages to attract fish, and once these fish bumped up against the bars they would emit the sort of sounds that attract dolphins. Once the dolphins got into the habit of frequenting this area, they would very likely start completing the north-south passage across the deep water.

Environmental activists are very doubtful about the idea of training the dolphins to get across the deep water, and point out that there is no precedent for it anywhere in the world.

Samuel K. Hung of Hong Kong, who has been studying the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins for many years, says it is impossible under natural conditions to train wild dolphins to swim through a specified area. At Hong Kong's Chep Lap Kok International Airport, for example, there is a one-kilometer wide channel between the airport and Lantau Island that was frequented by humpback dolphins prior to construction of the airport, but since land reclamation was carried out to make space for the airport, researchers have not spotted a single dolphin there in nearly 100 trips to the area.

In response to her many critics, Chou Lien-siang points out that her proposals are all experimental in nature and success is not guaranteed, but she isn't just taking shots in the dark, either. In addition to her own animal behavior research, she has also consulted with experts from around the world to discuss her ideas, and she didn't put forward her proposals without first confirming at least the possibility of success. A lot of details remain to be ironed out, to be sure, but she feels that environmentalists should not dismiss experts out of hand just to oppose the Kuokuang project.

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins living along Taiwan's west coast number less than 100, and have been classified as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Another focus in the debate over humpback dolphins is the question of whether their population has been steadily declining each year. Is the existence of separate populations in the north and south the consequence of long years of heavy industrial activity on the coast of central Taiwan?

Because academic research on the humpback dolphins only began five years ago, there are no records to indicate whether the total population has been decreasing year by year, but based on comprehensive reviews of overseas research and other data, environmentalists generally agree that the current population is a lot lower than in the past.

The fishing industry has an adverse impact on Taiwan's humpback dolphins, fully one-third of which bear injuries indicative of past entanglements in nets or collisions with ship propellers. Research from Hong Kong indicates that 8.9% of the humpback dolphins at the mouth of the Pearl River bear obvious scars. In the meantime, overfishing deprives the humpback dolphins of their favorite foods. Small fish and shrimp as well as squid, octopus, and other cephalopods are steadily declining. Humpback dolphins are being forced to search further and further for food, thus expending more energy in the process. This lowers their survival rate.

As for pollution, work done by cetacean specialist Chris Parsons suggests that the discharge of industrial wastewater is causing excessive concentrations of DDT as well as mercury and other heavy metals in the humpback dolphins living in the waters of Hong Kong, and it affects their health and reproductive success.

On a visit to the coastal Changhua fishing villages of Fangyuan and Xianxi, this reporter heard many fish farmers comment that since the Formosa Plastics sixth naphtha cracker was built, "the venus clams grow real slow," "the oysters' shells have turned black," "we don't catch as many fish, and they've gotten smaller".... And if the Kuokuang Petrochemical complex adds to the pollution? They can't hide their apprehension: "We'll be goners!"

Professor M.H. Chen of the National Sun Yat-sen University College of Marine Sciences warns that the sea's capacity to dilute is so immense and changes in its composition so minute that by the time we notice change, the problem is already extreme. Factories in Taiwan's industrial parks will all tell you that their discharges are in line with standards, but the cumulative discharges after 20 to 30 years must be considerable.

Industrial parks and major development projects on Taiwan's west coast

Current research has identified five threats to humpback dolphin populations: habitat destruction; pollution; noise; insufficient food sources; and the impact of the fishing industry. But how big a problem is each one of these? Current research and data do not yield definitive answers to that question.

In addition, there hasn't been any local research on the feeding patterns, reproductive rates, or other basic factors of the humpback dolphin ecology. Are the humpback dolphins of Taiwan and mainland China a single variety? Do they interact at all? No one knows. Oceanographers and environmentalists generally agree that given the paucity of information on the humpback dolphins, it would be entirely too risky to rush ahead with a decision regarding industrial development.

The overwhelming majority agrees on one thing in the controversy over the humpback dolphins: "Ultimately, the best way to protect the humpback dolphins would be to establish a marine sanctuary for them."

Professor Lee Pei-Fen, director of National Taiwan University's Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Allen Chen, a research fellow at Academia Sinica, call attention to the fact that the humpback dolphins are listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The government must handle this matter with great care, lest it incur international sanctions. If our humpback dolphins were to get as close to extinction as China's Yangtze river dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer), Taiwan would became a case study in how not to preserve an endangered species.

The humpback dolphin is quite unusual in appearance, for it matures to either a white or pink color, and features a camel-like hump on its back, thus the "humpback" in its name. The grey humpback dolphin in the foreground is not yet mature.

The government has kicked into gear on the humpback dolphin issue in recent years. The Council of Agriculture is conducting a study of important humpback dolphin habitats, and hopes to release it early next year. The Fisheries Agency is enforcing a prohibition on bottom trawling within three nautical miles of shore, and is evaluating a plan to establish a fisheries resources sanctuary or a no-fishing zone. And the National Council for Sustainable Development steps in to coordinate between different cabinet-level agencies when disputes arise that involve environmental versus economic development interests.

The Kuokuang Petrochemical complex is not the only issue on the table. Plans are also in the works for expansion of the Formosa Plastics sixth naphtha cracker in Mailiao and the Taipower thermal power plant in Taichung. These developments, together with the wastewater discharged by the optoelectronics manufacturers in the Central Taiwan Science Park, could all "terminate" the humpback dolphins. Chou Lien-siang suggests that the government ought to elevate the issue of maritime preservation to the level of "national land planning." She calls for a thorough survey of all Taiwan's maritime resources to identify first- and second-level preservation priorities, rather than scurrying to find funding for studies in reaction to economic development proposals.

Being at the top of the food chain, cetaceans are an indicator of the health of the marine ecology. The remaining 80-plus humpback dolphins are sending us a clear message about the state of the ecology on Taiwan's west coast. As a small island, can Taiwan actually afford to develop the petrochemicals industry, plagued as it is by pollution, high carbon emissions, and a voracious need for water? Is it worth the loss of the beautiful humpback dolphins and the last big wetlands on our west coast? This is a value judgment that deserves some serious thought.

Wu Zhucheng, who runs a clam nursery in Fangyuan Township, says that the venus clams don't grow nearly so fast anymore since the Formosa Plastics sixth naphtha cracker was built. They used to reach harvesting size in a year, but now it takes a year and 10 months, which is why local fishermen oppose plans for the Kuokuang Petrochemical complex.

The controversy over the humpback dolphin highlights longstanding deficiencies and lacunae in Taiwan's marine conservation efforts. Scholars have called for the conservation of marine resources to be approached with the same breadth of vision as national land planning.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)