Raising the Public's Compassion Quotient

Chen Hsin-yi / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by Scott Williams

January 2010

The end of the year is the season for chilling winter winds. It's also the season for something warmer-compassion. For both individuals and profit-seeking corporations, it's the time of the year for giving back. A "red envelope" given to charity at year's end embodies a hope for the prosperity of the nation and the security of its people.

Taiwan, which places great store in compassion and justice, donated more than NT$10 billion to help the victims of 2009's Typhoon Morakot-related floods. But information societies also foster public debate, and in Taiwan that has meant a corresponding increase in the public's "compassion quotient." Now, more and more people are asking: What kind of giving provides the most tangible help? Who oversees the expenditure of donations? Are our donations being put to good use? And, how should we feel about the crowding-out effect of disaster-relief fundraising?

A 2003 survey by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) shows that in years without a major natural disaster, Taiwanese donate nearly NT$42.7 billion to charity, or about half the amount of the government's annual social welfare budget. The survey also showed that individuals over the age of 45 provided the lion's share of their giving to religious groups and political parties. The largest recipients of charitable giving (which excluded donations to political parties) were religious groups, which received more than 50% of the total. Another 37% went to social welfare organizations, and roughly 10% to educational, environmental, and arts-related groups.

Have you ever been confused by the myriad fundraising campaigns underway in Taiwan? Did you know that you could monitor how charities spend your donations?

The massive volume of donations reflects the rapid increase in Taiwan's social and economic strength since 1980. But prior to the 2006 passage of the Act Governing the Solicitation of Donations for Social Welfare Purposes the only oversight consisted of the outdated and inadequate Regulations on Consolidated Fundraising Campaigns. Fervent opposition from religious groups has kept draft legislation covering religious organizations, which would bring transparency to their financial operations, languishing in the legislature for years.

A study by the United Way of Taiwan, which serves as a fundraising portal for non-profit organizations (NPOs), found that 42% of adults had donated to public-welfare organizations, and that their three biggest reasons for giving were to do a good deed, because the donor identified with those whom the public-welfare organization served, and because it was the donor's custom to give to charity.

Chou Wen-chen, secretary general of the United Way of Taiwan, explains that, setting aside the religious desire to "accumulate virtue and seek karmic rewards," Taiwanese charitable giving tends to be spontaneous and driven by events that stir compassionate feelings. "When people hear about tragic events, they immediately reach for their wallets," says Chou. "They don't look too closely at who or what they are giving to, and rarely show much interest in what happens afterwards."

The lack of a well-developed legal structure and the impulsiveness of donors allowed some 215 fundraising groups-most with little verification of who they were and no operational experience-to spring up in the wake of 1999's Jiji Earthquake and rake in an explosion of NT$31.5 billion in donations for earthquake-related relief. Thereafter, controversies emerged on a number of issues, including charitable groups' too-rapid release of relief funds into the disaster zone, news organizations' use of donations to purchase satellite news gathering vehicles, the government's use of donations to cover labor, farmers', and fishermen's insurance premiums, and fundraisers' misappropriation of millions of NT dollars of donations to purchase ads touting their own achievements. Such events finally made the public aware of the possibility that its compassion was being abused. As a result, in December 1999 the Ministry of the Interior put together a draft of the Act Governing the Solicitation of Donations for Social Welfare Purposes and private groups began giving serious thought to self-regulation.

Taiwan doesn't lack for compassion. Over the last 20 years, the Chinese New Year Party for the Homeless organized by the Genesis, Zenan, and Huashan Social Welfare Foundations has grown from 10 to more than 1,000 tables of guests spread throughout Taiwan. However, donations have recently declined as a result of public concerns about large property purchases made by the owner of all three foundations, a lesson the rest of the social-welfare community has taken to heart.

After the Jiji experience, "Taiwanese society began equating donor rights with consumer rights," says Chou. But self-regulation was needed in addition to legislation. In other nations, alliances of NPOs have been operating oversight mechanisms for years. These mechanisms, which are independent of both the government and the private sector, are charged by the alliances with auditing their members, and in so doing help donors make decisions about where to donate.

In Taiwan, some 30 NPOs from different fields founded the Taiwan NPO Self-Regulation Alliance (TNPOSRA) in late 2005 and pledged to adhere to four principles of self-regulation: organizational governance, fundraising accountability, service efficiency, and financial transparency.

Chang Hung-lin, secretary general of the TNPOSRA, explains that the alliance holds itself to standards higher than those set forth in the law. Members post all of their annual financial statements and job reports on the alliance's website where they can be viewed by anyone.

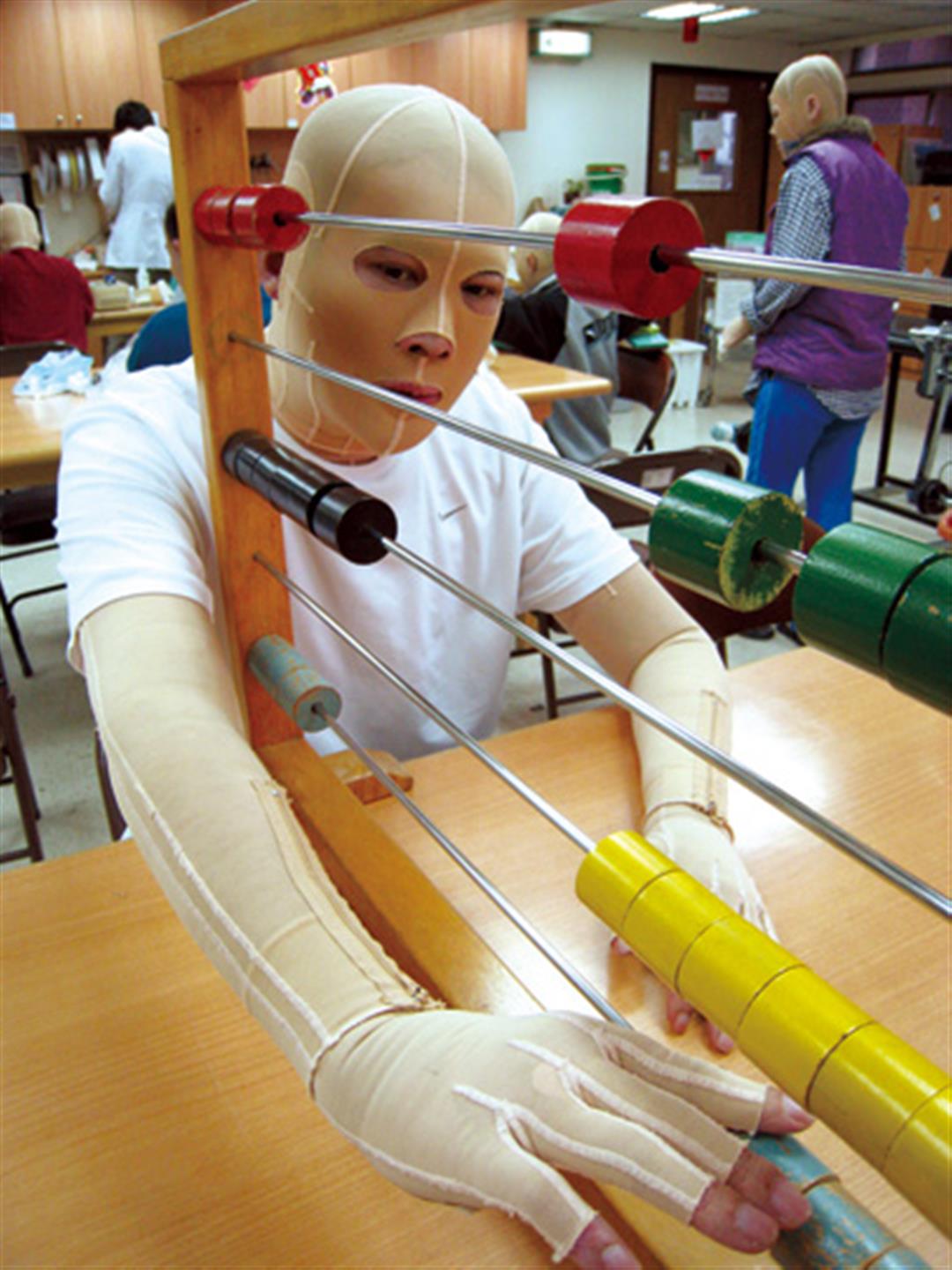

Some argue that differentiation benefits NPOs, and that the delivery of diverse, high-quality services requires that resources be well distributed. In the photo, Sunshine Social Welfare Foundation clients undergo therapy at a physical rehabilitation center. The therapy is aimed at preventing the joint contractures and deformities that can result from long-term immobilization and hypertrophic scarring.

The alliance also urges the public to be as selective with their donations as they would with investments in the stock market. If you're going to start a virtuous cycle, you have to be an intelligent "social-welfare investor."

"NPOs use other people's money to achieve their objectives," explains Chang. "You should be cautious and demand a return on your investment even more vigorously than you would with a company!" For example, if an environmental group in which ordinary citizens have "invested" is well run, it can stop tens of millions of NT dollars in inappropriate development, which will in the long term protect endangered species. That's a very clear benefit.

So far, 100 organizations have joined the alliance. "That means that NPO budgets worth NT$950 million a year have been voluntarily made transparent and accountable," says Chang. TNPOSRA's membership includes 63 social-welfare, 21 educational, nine medical, four environmental and animal conservation, two arts, and one media group. Perhaps the most heartening thing to members is that the Public Television Service Foundation, a public entity with an annual budget of NT$900 million, has also joined.

"On the other hand," Chang says, "there are some groups that refuse to join the moment they hear that they'd have to make their financials public." He explains that some corporate-backed family-run foundations feel that since their funding comes from the boss's pocket, there's no need to make such information public. Chang disagrees. "Corporate-backed foundations enjoy tax write-offs and are established in keeping with the prerequisite that they be 'public goods.' As such, they have no grounds for using claims of 'privacy' to avoid accountability."

Volunteers comfort victims in the immediate aftermath of the storm, reminding them that their lives are more valuable than any possessions they might have lost and that they are not alone.

If we view this casting about for an oversight mechanism and the controversies surrounding charitable giving as society's collective learning process, then the fundraising inspired by 2009's Typhoon Morakot offers a test case for determining whether the public's "compassion quotient" has increased.

Chou, a long-term proponent of the "donor rights" concept, observes that individual and corporate donors reflect on and learn from each major fundraising campaign. "Though these changes are rarely reported by the mainstream media, online communities offer a glimpse into the public's growing concern with accountability and into the thought people are giving to their own actions," says Chou.

For example, the week after Typhoon Morakot, there were people online urging others to stay passionately engaged, but to wait a little before giving money and to keep track of how their money was spent. Others reminded potential donors: "Don't hesitate to ask questions before making a donation. Has the organization provided a clear plan of action? Does it have the professional know-how to put our compassion to work?"

There has also been a major breakthrough in the mobilization of corporate resources. Whereas corporations used to just hand over donations to the government, Chou says that this time many were more interested in themselves mobilizing key resources and actually participating in relief efforts.

For example, Microsoft joined with its strategic partner ASUSTek Computer, Inc. to provide 350 free notebook computers to reconstruction teams working in the disaster area and assigned personnel to assist in the construction of a Typhoon Morakot Service Alliance information portal. Meanwhile, in addition to donating materials, President Chain Store Corporation (the franchise owner of Taiwan's 7-Eleven convenience stores) offered its logistics know-how to the government of hard-hit Pingtung County.

Chou's third positive observation is that people make good use of the Internet to gather and disseminate information. "Actions taken in the first moments of this relief effort-things like setting up information portals and using BBS's to put together teams of mountaineers to deliver relief to villages deep in the mountains-were firsts," says Chou. On the other hand, Chang Hung-lin argues, "Perhaps government bureaus should train 20 or so 'web gurus' who could flag inappropriate or incorrect information."

Though the merciless floodwaters washed away people's possessions, they also demonstrated the tenacity of ordinary people. In the photo, an armored vehicle evacuates residents of Linbian Township from the Typhoon Morakot disaster zone.

As the public's "compassion quotient" slowly rises, we need to ask: will the private bodies that mobilize giving and the corresponding government departments respond to the public's increasing scrutiny and perceived power?

If we compare charitable giving after Typhoon Morakot to that following the Jiji Earthquake (see table, p. 75), we find that the total amount given was roughly the same, but that the number of fundraising institutions fell from 213 to 45, indicating that the Act Governing the Solicitation of Donations for Social Welfare Purposes did indeed impose some constraints.

However, as the initial stage of the Typhoon Morakot rescue efforts came to a close, a TNPOSRA report on fundraising accountability and resource utilization found that several issues remained:

First Social Welfare Foundation, which specializes in delivering early treatment and behavioral counseling to the mentally handicapped, is unstinting in its efforts to train personnel. It is the matriarch and the R&D department of the social-welfare community.

Though most groups published their donor lists online, in print publications, or via their own media, they offered only the simplest explanations (or none at all) of their fundraising plans and how they intended to use the money they raised.

Red Cross volunteers and staffers worked daily from dawn to dusk issuing receipts for the flood of donations that came pouring in after Typhoon Morakot, then the staffers wrote several hundred more at home every night. By the time they completed their mission one month later, they had mailed out some 610,000 receipts.

A survey by the Ministry of the Interior's Department of Social Affairs released 10 days after the typhoon struck showed that the actual amount of funds raised by some private charities far exceeded the estimated cost of the projects they had proposed. The NT$11.55 billion raised by December 2 was double the initial NT$5.7 billion target and was highly concentrated among the biggest charities.

Chang says that when faced with "excess" charitable giving, these groups chose to forge ahead rather than hit the brakes. The problem was that they didn't necessarily go out of their way to inform the public about what kinds of projects they added to soak up the extra funds. In addition to raising questions about an institution's honesty, this practice can also lead to resource duplication, wasteful projects, and blind investment.

Some alliance members privately remarked that the big groups were profligate when bidding on projects during the government's post-typhoon reconstruction conference. "They were haggling like you would in a vegetable market," said one. Flush with cash and under heavy pressure to get projects going, when one group said it could put up 100 prefabricated homes, another would say it could build 200, and when one promised to build sustainable two-story housing, another would offer three stories.

After the typhoon, thirty-somethings utilizing the PTT bulletin board were able to arrange several truckloads of materials and volunteers to pack and deliver them within a day.

Under current fundraising legislation, when disaster strikes, central and local government departments may immediately solicit donations without first applying to the Department of Social Affairs (DSA). Alliance members worry that although the government has rules on spending, if it solicits donations without having already developed plans for how they will be spent and without an audit mechanism, there might be instances in which donations end up being used in the general budget or in which resources are duplicated.

Under pressure from the alliance, the DSA, which oversees fundraising, has moved to tighten up enforcement-actively gathering fundraising data from the city- and county-level competent authorities and calling charities weekly to press them to update their data. As a result of this exercise of public authority, the MOI's oversight system for charitable fundraising now includes information on planned uses of funds and accounts of how funds were actually spent for 70% of Taiwan's private charities and almost 90% of its government charities.

In addition, to better match private resources to the needs of the six counties and municipalities ravaged by the typhoon, the DSA convened several coordination meetings, permitting local governments to itemize their needs and their estimated costs and giving private groups the opportunity to consider which projects to "adopt." Local governments welcomed the approach, which avoided problems associated with the unequal distribution of resources and the tendency of high-profile disaster areas to get a disproportionate amount of aid. The DSA has also continually exhorted city and county governments and township administrations to avoid including public works projects or projects which already have special budgetary allocations on their list of needs. That is, the DSA is insisting that donations be spent on victims of the disaster.

Though the alliance is full of praise for the hard work of the central government authorities, Chang stresses that the only way to ensure that charitable donations are well used is to revise legislation to require more accountability from charitable groups and to make it easier for the public to acquire information on charities.

The crowding-out effect

Fundraising campaigns related to major disasters or heart-wrenching events are the focus of another controversy-the crowding-out effect. Experience shows that when the economy is struggling and after the period of feverish giving that follows major disasters, routine giving by individuals and corporations falls, reflecting the fact that the wellsprings of compassion run dry and wallets go empty.

Individual organizations respond to this in various ways depending on their size, the nature of their services, and their clientele.

Take the 28-year-old Sunshine Social Welfare Foundation, for example. Long-term small donors provide 55% of its income, which leaves it very vulnerable to economic upheavals. "Fortunately, though the amount given by individual donors has shrunk (from an average of NT$900 in 2007 to just NT$700 in 2008), the number of donations has not fallen much," says Jamie Wong, the foundation's director of promotion and education. "Tightening our belts will get us by." Wong says that Sunshine has held fast to its mission over the years, helping rehabilitate burn survivors and victims of facial disfigurement and get them back into the community. "The key is to make the public aware of the value and extent of your services," says Wong. "If you can do that, donors will continue to support you."

When disaster strikes, the foundation's first actions are to determine whether there are injured persons in or near the disaster zone in need of its assistance and to encourage employees to donate one day's salary. "But we don't take on relief tasks we don't know how to handle, nor do we use this as a pretext for hasty fundraising," explains Wong.

Lai Chin-lien, a researcher with the Syinlu Social Welfare Foundation, says that small groups that don't have specialist fundraising personnel saw their donations fall by 30-40% after Typhoon Morakot. Syinlu, on the other hand, derives nearly 70% of its funding from government subsidies and parents of its clients, which makes its finances relatively stable.

Lai often travels to central and southern Taiwan to share her financial management and fundraising know-how with local NPOs. She encourages small and medium-sized groups to put down roots in their communities and unearth local resources. "We need to work together to enlarge the social welfare pie, to shift from competitive to cooperative relationships," she says.

Everyone enjoys doing good deeds, and every little bit helps. The photo was taken at the 20th annual 30-Hour Famine held in the Linkou Stadium in 2009. The 16,000 "campers" who participated in the event, sponsored by World Vision Taiwan, fasted for 30 hours to raise funds for undernourished children and victims of Typhoon Morakot.

Joint fundraising is a method used to resolve the crowding-out problem. Now in its 18th year, the United Way of Taiwan raises more than NT$300 million per year. While that's only 0.8% of Taiwan's total charitable giving, it means material support for "small but necessary" organizations. The United Way, which backs more than 500 assistance programs, claims that "a single donation helps 10 people" and advocates "compassion that leaves no one out."

Chou says that all the social welfare groups that accept United Way funds are closely supervised by United Way examiners and auditors, and that their reports are available to the public. If even a single subsidy is used in a manner that is inconsistent with expectations, the United Way has the right to demand that it be repaid.

Contributions to the United Way of Taiwan have grown steadily in recent years. With more than 50,000 people now donating every year, it is clear that group's "reasonable distribution, professional oversight" model has gotten through to the public.

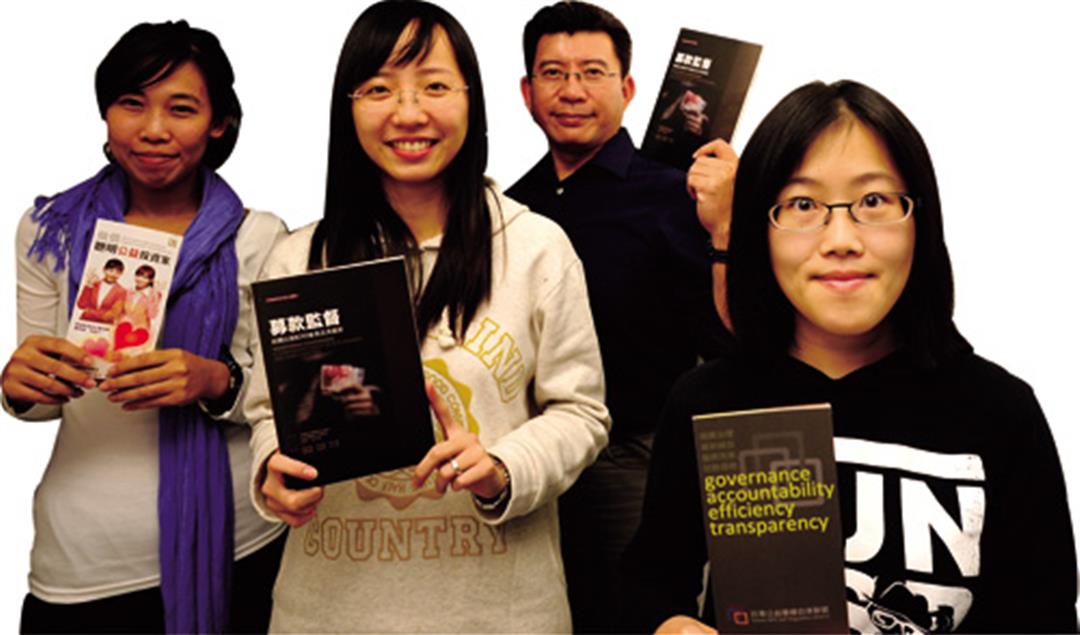

"The trustworthy public-welfare groups have all joined," says Chang Hung-lin (second from right), secretary general of the Taiwan NPO Self-Regulation Alliance. Chang says that membership includes both duties and privileges. Members must be "open and transparent" about their operations, but are also provided with the opportunity to take classes with experts on social-welfare work and to register with the Yahoo! Kimo fundraising portal and with Taiwan Mobile's donations number, 5180.

Joyce Yen Feng, a professor in the Department of Social Work at National Taiwan University, has long been interested in the development of NPOs and accountability issues. She says that ideally demands for accountability and public-mindedness from NPOs should be jointly overseen by four forces: each organization's own independent, autonomous board; NPOs' collective self-regulatory mechanism; government policy and legislation; and a proactive media. At the same time, she argues that, to prevent excessive legislation from weakening the idealism and self-regulatory power of the NPOs, government regulation should remain merely a supplemental framework.

Looking ahead, Taiwan's only self-regulatory platform, TNPOSRA, is urging more organizations to sign on to its self-regulation covenant, which it sees not just as a means by which groups can exercise oversight and support one another, but as the only way to forcefully demand that the government strengthen its orientation towards fostering the good and weeding out the harmful.

To return to the original point, we as donors should spend a little extra time being smart about charity if we are to ensure that Taiwan's charitable endeavors, "society's last line of defense," become better established and more robust.

Major fundraising campaigns

| aJiji Earthquake | Typhoon Morakot *already spent | |

| Government fundraising | 167 | 75.73 *74.43 |

| Non-governmental fundraising | 148 | 115.96 *37.31 |

| Total | 315 | 191.70 *86.74 |

| Five largest non-governmental fundraisers

(Unit:NT$1 bilion) |

Tzu Chi Foundation (5.0) Red Cross (1.8) TVBS Foundation (1.17) Puli Christian Hospital (0.61) TTV (0.6) -Total: 9.18- |

Tzu Chi Foundation (4.58) Red Cross (3.57) World Vision Taiwan (0.75) TVBS Foundation (0.59) Chang Yung-fa Foundation (0.46) -Total: 9.95- |

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)