Director Wu Nien-jen on Taiwan's Gold Towns

Chen Hsin-yi / photos courtesy of Tourism and Travel Department, New Taipei City Government / tr. by Chris Nelson

November 2011

What pops into your mind at the mention of Jiufen, the tourist spot in northern Taiwan most popular among visitors from Hong Kong and Japan? Mouthwatering street eats? Or maddening traffic jams, perhaps? The mournful expression of the protagonist in the film A City of Sadness, or nostalgic red lanterns hung high outside teahouses?

Jiufen, a gold mining town turned tourism goldmine, is a sensory kaleidoscope that people both love and hate. Oddly enough, Jinguashi, another gold mining town a quarter of an hour's drive away, has long retained its relatively understated character. And toward the sea is the even quieter old mining town of Shui-nandong, which really satisfies that longing for a return to the Taiwan of old.

Given the rich and varied tourism resources of these three gold mining towns, the New Taipei City Government has spent the last year or so refurbishing historic sites in the area, and has appointed Taiwan's great storyteller, film writer and director Wu Nien-jen, to serve as spokesman in hopes of reshaping the allure of these three towns.

Director Wu's leading the way! Are you ready to join him?

A weekday morning in Jiufen: most shops are yet to open and tourists are few and far between. Then a commotion erupts at the little plaza where Jishan Street, Shuqi Road and Qingbian Road converge, with many older townsfolk and news crews gathering together, restlessly waiting to enter the venue. It turns out that the long-neglected Shengping Theater is about to reopen!

Built in 1934 as a venue for Taiwanese Opera, the Shengping Theater originally consisted of one story made of stone topped by a second made of wood. Later it was rebuilt in reinforced concrete to form a three-story building, northern Taiwan's first cinema.

The now-restored Shengping Theater retains its old facade and its mixture of Eastern and Western architectural styles, and boasts 300 seats. Here they screen films written and/or directed by Wu Nien-jen, and all set in these mountain towns, on a regular basis; there's also space for exhibits and lectures.

On opening day, Wu, the special guest and a former local resident, was overwhelmed with emotion. "I never thought that when I was 60 years old, this theater would be restored, screening my films. When I was inside, I saw scenes from my childhood come to life; I recalled people and things I don't normally think of," says Wu.

Jiufen's Qingbian Road is chock full of artistic ambiance.

Half a century ago, long before Jiu-fen's current incarnation as a tourist destination, it was nonetheless remarkably similar in character to how it is today, with crowds jostling each other shoulder to shoulder in the alleys, and nightly dance parties. Wu was six years old when he first experienced the magic of the silver screen, and this was at the Shengping Theater.

In Wu's film A Borrowed Life, largely based on his own childhood experiences, the emotionally repressed, non-communicative father shows his affection for his brilliant son by taking him to Jiufen to see movies. "My Japanese friends are totally knocked out when I tell them how many of the Japanese films of that era I saw as a kid," says Wu.

Wu's father was originally from Chiayi. Harboring vague dreams of gold prospecting in his youth, he headed up north, alone, carrying a small pack, and ended up in Dacukeng, a backwater district on the outskirts of Jiufen. Starting out by working odd jobs at an ore crushing plant, Wu at age 19 volunteered to become the adopted son of a couple who had lost their child; he soon married a local woman, raising five children, and spent nearly 30 years working deep inside dark, dank, dangerous mines, eking out a living by sweat and toil.

Back then there was only one road out of the village. It took over 40 minutes to walk to either Houdong or Jiufen, with no streetlamps or houses by the roadside; only a gloomy "wandering ghost temple" and the occasional wild animal. But to the people of Dacukeng, the consumer paradise of Jiufen was "not far at all." After a hard day's work, it was a trivial matter to round up a group of friends and walk over to Jiufen.

There was a little secret between father and son back in those years, and a similar scenario is shown in A Borrowed Life. Wu's father would take his son to Jiufen, telling his wife they were going to catch a movie, but his real aim was to go drinking and gambling with his buddies. So when they got to Jiufen, he would send young Wu Nien-jen to the cinema, go out drinking, and come back later to pick him up. The elder Wu would then listen to his son recount the plot as they walked home under the moonlight, so he could pass his wife's "spot checks." "Perhaps my ability to write screenplays is connected to my frequent storytelling as a child," says Wu.

The restored Shengping Theater in Jiufen.

You might be curious, when gold fever drew people to settle in both Jiufen and Jinguashi a century ago, as to why the former imparts a flamboyant, chaotic impression, while Jinguashi seems neat, orderly and more serene.

Shih Chen-yi, a resident of Shui-nandong and former acting curator of Jinguashi Gold Ecological Park, explains that Jiufen and Jinguashi are like brothers, the former with a more ebullient personality and the latter more conformist like a government functionary. This is because the mining rights for Jiufen had been secured by the locally owned Tai-yang Mining Company, while Jinguashi was under the unified authority of Japanese management during the Japanese occupation. Since the Tai-yang Mining Company hired labor through subcontractors, those with an adventurous spirit and dreams of hitting the motherlode tended to gravitate to Jiufen. Legends of overnight riches and the live-for-the-moment miner culture spurred the intense entertainment and recreation of Jiufen. "By the time the first lanterns were lit in Jiufen each night, the residents of Jinguashi would already be sound asleep."

But then the whole area underwent a dramatic transition from riches to rags. The ore deposits of Jiufen and Jinguashi were exhausted by the early 1970s, and Wu's father lost his job, moving to Houdong to work in the coalmines.

In 1975, when the Jui-San Mining Company in Houdong, run by founder Li Jianxing, was on the verge of closing down due to excessive costs and depleted ore deposits, all seven members of the Wu family bade farewell to their home and mining life. By 1976, not a soul lived in Dacukeng, and its formal administrative name, Dashan Ward, was officially abandoned.

Still, to this day old neighbors, who formed a tight-knit community long ago, meet regularly. But some of the older folk have passed away from silicosis contracted from their mining careers, to the dismay of the younger generations.

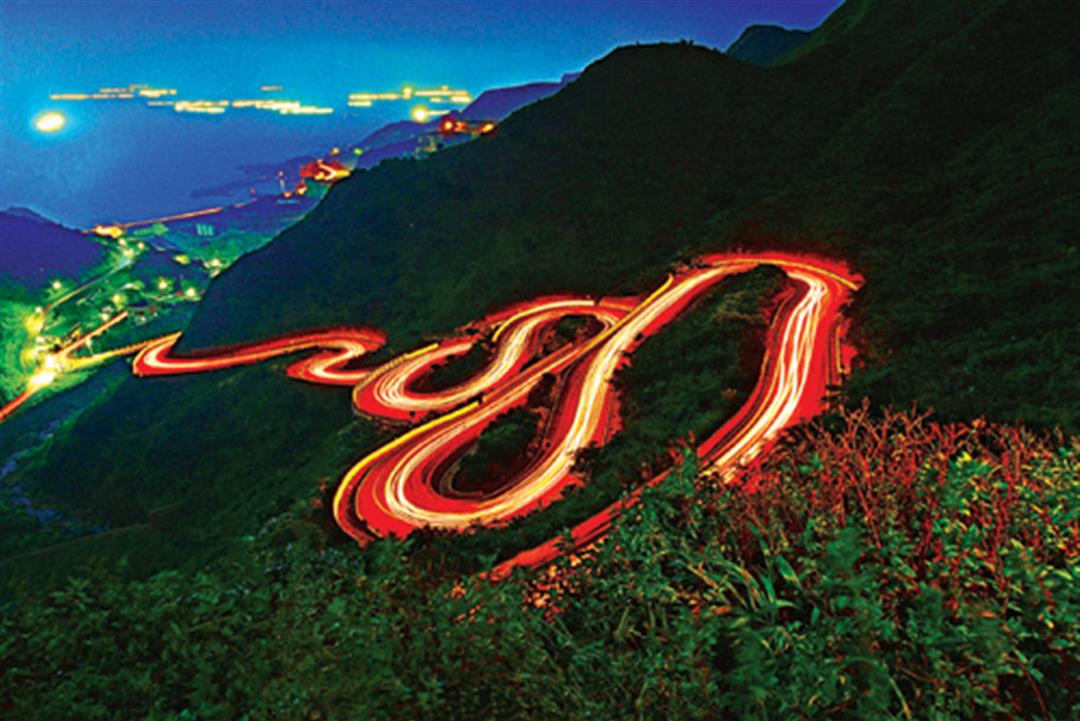

The winding county road leading from Jinguashi toward the coast to Shuinandong was once an industrial road. Today locals call it the "Romantic Highway."

For Wu, leaving home was just the beginning of even more stories. In the 1980s there was a boom of Taiwanese New Wave cinema, and Wu, a newcomer to the film industry, pushed his friends to shoot films in Jiufen, unknowingly becoming the impetus behind Jiufen's resurgence.

"Jiufen is as glorious now as it was before its decline. Like a white-haired old lady, wearing simple, tidy clothing and sitting in the doorway sewing clothes in the sun when the weather's good: the stories she tells leave you spellbound," says Wu.

When his good friend Edward Yang first came to scout locations in Jiufen, he found what would become a classic image in That Day on the Beach: the winding mountain path to Jiufen Elementary School. He also spotted the Peng Clinic, which would serve as the lead character's home. Says Wu, "When Dr. Peng heard me mention that my father was from Dacukeng, he generously allowed us to use it as a location." (The building has since been privately donated to the government and designated a historic site.)

Childhood impressions of the mountain town vistas have been writer-director Wu's inspiration since Day One. Wu once wrote a haiku for director Wan Jen's Super Citizen Ko, which was about the White Terror, wondering why, though the mist has lifted and all can be seen clearly, everything there is covered with teardrops.

Wu recalls that by the time they shot A Borrowed Life, Jiufen's popularity had grown considerably, and tourism was causing its appearance to change rapidly, "I had to go shoot in Pingxi and Houdong." At the mention of overdevelopment in his hometown, Wu, now a tourism spokesman, sighs: "Today's Jiufen is still in essence an old lady, but now with some rouge on her face, and from time to time she calls out to customers to come in and grab a seat!"

The remains of the push car railway station in Jiufen are now a privately owned restaurant.

These last two years, the New Taipei City Government has been pushing a tourism development plan for these three towns, with the aim of de-emphasizing the food-and-drink-oriented whirlwind visits that easily cause traffic jams. They have renovated certain historic areas (including the Shengping Theater, Jinguashi's Qitang Old Street, Taiwan POW Memorial Park, and Shui-nandong's art galleries), trained over 100 local docents, and provided convenient bus lines linking the three locales, so that visitors can relax, slow their pace, and revel in the splendor and elegance of these mountain towns.

It's worth mentioning that quite close to the Gold Ecological Park sits the relatively little known Taiwan POW Memorial Park, site of the infamous Kinkaseki POW Camp, an indelible page in this town's history. At the end of World War II, over 1,000 allied POWs were secretly held here by the Japanese, forced to labor in the mines. Many lost their lives here due to harsh treatment and poor acclimation, but those that survived the horrors experienced the camaraderie of fellow prisoners from around the world.

After the war, repatriated survivors joined together to form an international society, compiling a list of all the victims, and returning each year to the ruins of the camp's gateway in remembrance.The newly renovated site features a memorial wall onto which are engraved the names and nationalities of over 1,000 victims, demonstrating a sentiment of friendship and peace.

Wu, as top spokesperson for the area, makes this appeal: "Just take a stroll amid the mountains; this is still northern Taiwan's most atmospheric area. The key is in slowing your pace and appreciating what nature has to offer."

As fall weather arrives and the silvergrass blooms, come visit these mining towns, take a stroll and experience the power of nature and the spirited stories of this area. It'll blow you away!

The ruins of old sluices at Jinguashi: the upper levels are Japanese built, the mid-level is from the post-war period, and the lower level was constructed in the Qing Dynasty.

The remains of the ore refinery at Shuinandong, known as Shisanceng ("13 levels").

With director Wu Nien-jen showing the way, the history of each nook and cranny of these three gold mining towns comes to light.

The ruins of the Kinkaseki POW Camp, where the Japanese army held Allied prisoners of war during World War II, are now the Taiwan POW Memorial Park.

Jiufen's Qingbian Road is chock full of artistic ambiance.

An old mine in Jinguashi's Gold Ecological Park.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)