Who’d have thought that researching stem cells and writing novels could both fit in one man’s schedule? The man in question is a noted doctor who specializes in hematology and oncology, the first surgeon in Taiwan to perform a bone marrow transplant. But as of 2012, he prefers to be known as the author of a historical novel. He is a 63-year-old newcomer to the literary scene: Chen Yao-chang.

A team of German scientists recently announced discovery of a “short sleep gene” that enables people who have it to thrive on just four hours of sleep per day. Such people tend to be extroverts with an extraordinary capacity for multitasking. One noted example was the great Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci, who was versed in both science and art.

Here in Taiwan, Chen Yao-chang is another “short-sleep dynamo.” A doctor and professor, stem cell researcher, columnist, and father of six, he has an intense interest in just about everything other than economic and legal matters. Despite sleeping just four hours a day, he is always energetic and doesn’t need to pop vitamins. All day long he busily takes phone calls as he scours the Internet for information. If he leaves on a five-day business trip, he’ll take 10 books along to read.

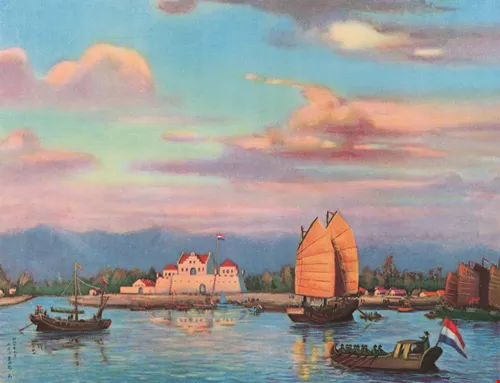

Lu’ermen, Tainan’s gateway to the sea, holds an important place in the history of Taiwan’s development.

He often tells med students that the pathway of life resembles not so much a set of rails as a network of rivers, one that abounds in opportunities and unexpected twists that you can take advantage of to reach out in many different directions.

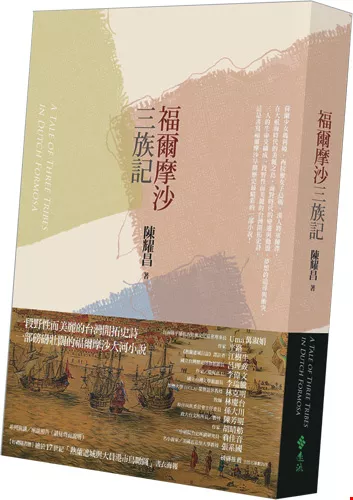

The multi-talented Chen has always been hard to pigeonhole, but it has just gotten even harder with the publication of his historical novel. A cheerful fellow who loves a good laugh, Chen exclaims with satisfaction that he has “finally done something good for Taiwan.”

On January 1st this year, the day that Three Families in Formosa was published, Chen posted to his blog to thank the publisher and his readers.

Publishing a full-length historical novel was something he had never expected to do.

The project got started in a most unusual fashion. On the evening of July 9th, 2009, in a hotel room in South Korea, Chen was keeping his accustomed late hours, poring through academic materials and entertaining his usual rush of thoughts.

For some reason, he set aside the stack of Korean biotech research papers he’d been reading, and his mind wandered off to 17th-century Taiwan. He had been very interested from youth in history, and his voracious reading gradually turned from world history toward the past of his native Taiwan. He eventually zeroed in on the period of Dutch rule and published several articles on the subject.

Tainan was once governed from Fort Provintia, which today is designated as a Class 1 Historical Site.

But the inspiration for his novel was something still closer to home—relatives said that there was Dutch blood in the family. The first he heard of it was seven or eight years ago when, during a trip back to Tainan to tend to a family gravesite, a septuagenarian uncle suddenly said to him: “One of our early ancestors was a Dutchwoman.”

Chen was thunderstruck, and inclined to believe his uncle on account of his own curly hair, bushy eyebrows, and long sideburns, as well as his father’s considerable height. His family had not kept a family tree, so there was no way to verify anything. But that only left more room for his imagination to run. Does a novel not start where information leaves off and imagination takes over?

History offers no end of unanswered questions, just as the human body does. And so every doctor is a detective. Chen set to imagining what life in the Formosa of old must have been like for the indigenous Sirayan people, the Dutch, and the Han Chinese. He thought about the collisions of their cultures, the exchange of their genes, the loves and hates. He imagined a Taiwan that was only just beginning to interact with the outside world, a land inhabited by people speaking many different languages.

Blessed with a boldly roaming imagination and rigorous powers of deduction, Chen got the urge for the first time in his life to write a novel about the Dutch period in an effort to unravel mysteries and provide a realistic interpretation of how life may have been in those times.

He had read 60 or 70 books on the topic, most important among them naturally being a diary kept by the Dutchman Philip Meij (Daghregister van Philip Meij) and a four-volume set of journals (De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia), translated into Chinese and annotated by Jiang Shusheng, a specialist in the history of the Dutch occupation. The journals provide important source material on the history of Dutch rule, while the diary offers valuable information on Koxinga.

Before starting on the novel, Chen first wrote an essay entitled “Building a Historical Concept of the Taiwan Hero,” which could be seen as a prequel to the novel to come. The basic idea of the essay is that the history of Taiwan seems dull and unrelated to the lives of everyday people because no heroes—such as Guan Yu, Zhang Fei, and Cao Cao in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms—have been put forward that would capture people’s imagination. Chen took it upon himself to give Taiwan history the hero it deserves.

That night in South Korea, Chen wrote up an outline for his novel on hotel stationery. His pen flew furiously across the paper, and in just two hours the outline was complete. The project was off to a surprisingly good start. Gazing at the outline, Chen grew confident. A dream appeared there before his eyes, within his grasp.

He didn’t set seriously to the task of writing the novel, however, until the following summer. In the interim, when he wasn’t busy seeing patients he was thinking about the structure and plot of the story. The task was on his mind constantly, and progress was slow at first. The spotty historical record had to be filled in with care. But once Koxinga made his appearance the historical record instantly became much more complete and Chen’s writing went more quickly. By the lunar new year of 2011, a fully developed picture of Koxinga as a “national hero” had been achieved.

Says Chen: “For the next step, it would be nice if I could get the novel adapted as a movie, or a Taiga drama. If I could get Ang Lee as director, it could be an international blockbuster.” (“Taiga dramas” are year-long TV historical fiction series broadcast by Japan’s NHK.) And who would play the part of the protagonist, Maria, who comes to Taiwan from the Netherlands along with her father? “I’m afraid Winona Ryder, who starred in The Age of Innocence, would be a bit too old for the part, but Keira Knightley from Pirates of the Caribbean would be good. And Takeshi Kaneshiro would be perfect for Koxinga. After all, Kaneshiro is half Chinese and half Japanese, just like Koxinga.”

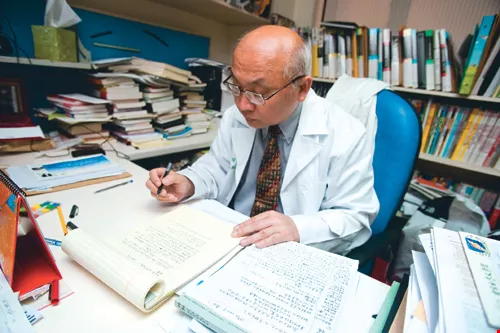

A messy desk belies the well-ordered mind of Chen Yao-chang, who pores through both historical records and medical texts in his office.

No one had ever undertaken the task of writing a historical novel on the Dutch period until Chen set his mind to it.

Perhaps it was just meant to be? Chen feels there is not another person more qualified than him to write Three Families in Formosa, for he was born in Tainan where the Dutch were based, he quite likely has Dutch blood in his veins, his long passion for Taiwan’s history has led him to publish on the subject, he is a medical professional, and as a writer he has benefited from the influence of Jurassic Park author Michael Crichton and the NHK’s Taiga dramas. The inspiration for Three Families in Formosa was sparked precisely by the jostling factors of ethnicity, place, history, literature, medical science, and Taiga dramas.

But only a person fired by a fiercely passionate nature could ever have carried a huge cultural undertaking like this through to completion.

One discovers that Chen’s friends almost always use the word “passionate” to describe him.

Chen’s father was a doctor, and his younger brother is a practicing physician in the United States. Unlike his brother, Chen returned to Taiwan after leaving a high-paying hematology fellowship at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s in Chicago. People sometimes ask the brother why Chen came back to Taiwan, to which the brother replies: “I have an affinity for science. He has an affinity for people.”

But that reply isn’t quite complete. It’s not that Chen doesn’t like science; he is simply a man of strong emotional attachments. At the time of the Zhongli Incident in 1977, he was the chief resident physician in the internal medicine department at National Taiwan University Hospital. It was a time of political unrest, when dangwai political activists were taking part in bloody street protests in their quest for democracy. When Chen saw a report in the United Daily News about the police department in Zhongli getting set ablaze, he shed tears at the thought that “the people of Taiwan have at last stood up.” Then when the Kaohsiung Incident erupted in 1979, Chen did everything he could in Chicago to collect news clippings on the subsequent trials. For him, Shih Ming-teh, Lin I-hsiung, and Annette Lu were the pioneers of democracy.

A messy desk belies the well-ordered mind of Chen Yao-chang, who pores through both historical records and medical texts in his office.

With his characteristic passion, Chen has also thrown himself into placental stem cell research. He is currently studying stem-cell-based immunotherapy.

When talk turns to his research work, Chen repeatedly stresses that stem cells can “repair” tissue, but not “regenerate” it. In addition, stem cells can be used to treat immune system diseases, and can protect cells. As well as using stem cells to treat multiple sclerosis, Chen’s research team has successfully completed initial animal studies in which they exposed lab mice to a simulated radiation leak. The team injected the mice with stem cells and found that some were able to survive.

Noting that there is no other national capital in the world located closer than Taipei to a nuclear power plant, Chen asks how we would respond in the event of a nuclear catastrophe. In his view, the Atomic Energy Council must prepare in advance by establishing a stem cell bank that could be used to treat citizens exposed to a radiation leak. This is what he is working on now. “The research I do is not remote from our everyday lives. I insist on doing something that Taiwan needs, and will benefit Taiwan in some way.”

His passion also carries over into a concern for politics. He joined the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), and served for a time as a National Assembly delegate. After former president Chen Shui-bian became embroiled in scandal, in an effort to stay above the fray in the contentious struggle between Taiwan’s blue and green political camps, he left the DPP and helped set up the Home Party, for which he served as the first party chairman. The party’s founding declaration clearly bore the stamp of Chen Yao-chang’s romanticism, quoting a witticism from the opening lines of Kurt Vonnegut’s A Man Without a Country: “There is no reason good can’t triumph over evil, if only angels will get organized along the lines of the mafia.”

Chen Yao-chang comes from a family of practicing physicians, and the excellent education he received at home laid the foundation for his later success. He is shown here in the 1950s as a tyke in his mother’s arms. The whole family is posing in front of their medical clinic to mark the wedding of Chen’s uncle. Second from the right is Chen’s father, and third from the right is his grandfather. Sitting next to the bride is Chen’s grandmother.

A person of a passionate nature is naturally a romantic, and this trait has made Chen a big fan of all the novels published by Michael Crichton.

“Crichton always collected a huge amount of information, then studied and digested it before turning it into a novel. All of his novels were on different topics. He is my idol.” Chen was heartbroken when Crichton passed away in 2008, and frustrated that he couldn’t have treated Crichton’s illness. “I would absolutely have brought him back to health.”

As a former visiting associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Tokyo, Chen is very fond of all things Japanese. He’s a big fan of manga author Kenshi Hirokane, but the series Chen likes best is Tasogare Ryuseigun (“Like Shooting Stars in the Twilight”), rather than Shima Kosaku, for which Hirokane is best known. It takes an older person like Chen, who has seen much of life, to really appreciate the undying quest for romance that Hirokane creates in the stories of middle-aged love that make up Tasogare Ryuseigun.

Chen caught notice for his passionate writing as a new student at university, where a professor of Chinese had glowing praise for his work. Writing was always very much an interest of Chen’s, so he accepted readily when, later in his career, several magazines sought to retain his services as a regular columnist. His columns would eventually be collected into two books.

The first of these was Phantom of the Biotech: My “Cellular” Life, in which Chen discussed biotechnology, the crisis of aging populations, and declining fertility. He also wrote in strong support of the many women from overseas who come to Taiwan as brides of local citizens.

With the story of Three Families in Formosa, set in old Tainan, Chen Yao-chang has added to our understanding of modern history in Taiwan. Shown here is a sunset scene at Fort Provintia, painted by Tokushiro Kobayakawa. The beautiful fort and the boats plying the river show that old Tainan was a vibrant city.

In the end, Chen’s passion resulted in the birth of a novel. Thanks to his rigorous training in research and academic writing, the task of collecting and sifting through reams of historical material was not so daunting. Before embarking on the project, he already possessed the basic skills he would need.

Having read countless surgery consent forms, Chen was intimately familiar with how to write in clear and simple language. And, as a medical professional, he did not shy away from making the bold deduction that Koxinga probably didn’t die from a heart attack or stroke, nor did he die “scratching at his face,” “biting on his fingers,” or “clutching at his face,” as has often been written. Rather, Chen argues that Koxinga must have committed suicide.

“Given his state of mind prior to death, his family history, and his personality, it is perfectly reasonable to suppose that he would have committed suicide.”

As an avid reader of Michael Crichton, Chen knows how to fill in the gaps where established facts are lacking. He knows how to rest a novel upon a solid foundation of knowledge, and how to hook the reader with a captivating story line.

Japan’s Taiga dramas, in the meantime, are consistently marked by a lack of absolutely good and bad characters. But those who perform their jobs faithfully are basically positive characters. This aspect deeply influenced how Chen developed his characters, good examples being Frederick Coyett (the last Dutch governor of Taiwan) and Koxinga—Chen measures both the colonizer and the colonized by the same yardstick.

Through his novel, Chen has brought back to life a world of the past. Three centuries is not such a terribly long time ago. By Chen’s estimate, a lot more people in Taiwan than we realize—probably about a million—have Dutch blood. In the multicultural Taiwan of over 300 years ago, the adventurous spirit of the Minnan Chinese molded a unique Taiwan culture that has continued to evolve over the succeeding generations and is now recorded in our genetic makeup, the code that has determined the fate of the people living here on this resource-poor island.

In his second book, Taiwan Dossier, Chen wrote movingly in the preface: “As a physician, I’d like to combine the kindness and literary talent of Dr. Zhivago with the forthrightness and integrity of Tomáš [from The Unbearable Lightness of Being]. But I’d like to be free of their loneliness and weakness. Furthermore, I’d like to have the ability to inspire people, and rouse them from lethargy. To the extent that my meager abilities allow, I’d like to be something in the history of Taiwan, something more than just a physician—I want to be an intellectual.”

That was 2008. Three years later, with the publication of Three Families in Formosa, he did indeed transcend the man he had been up to that point.

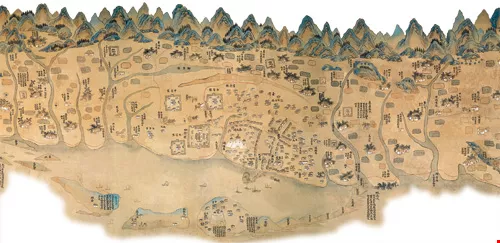

A hand-drawn map of Taiwan dating to the reign of the Kangxi Emperor.