Jade Craze--Unearthing the Liangzhu Relics

Jackie Chen / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Brent Heinrich

November 1993

China loves jade, admires jade, savors jade. It is called "Warm and lustrous, with a vibration heard far away, breakable but not bent, with a sharpness that does not hurt, like a fine gentleman."It is endowed with rich connotations and emotions.

When did this kind of tradition begin?Previous scholarship deduced that it possibly began at the time of the three dynasties Hsia, Shang and Chou. With the proof of present data, we know that as long ago as the New Stone Age, Chinese people were using jade as tools of worship. Liangzhu Jade, excavated in Yuhang County, Zhejiang Province, is evidence.

To pass from Hangzhou in mainland China to neighboring Yuhang County takes a drive of about half an hour. Just after crossing a little canal, the car enters Liangzhu Township, and some passengers exclaim, "This place is the world renowned Liangzhu, where the famous jade comes from!"

World famous, indeed, as the public relations representative for the Zhejiang provincial Artifact Research Institute describes it, with no exaggeration. From the biggest museums, such as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. and the National Palace Museum in Taipei, to jade markets, such as Cat Street in Hong Kong or the weekend jade market under the Chienkuo Bridge in Taipei, Liangzhu jade can be seen. Among all the old jades in the world, it very possibly ranks first. Its "abstract vision and realistic expression" (a jade trader's description) has swept the world of antique markets, and its impact is sure to last a long time.

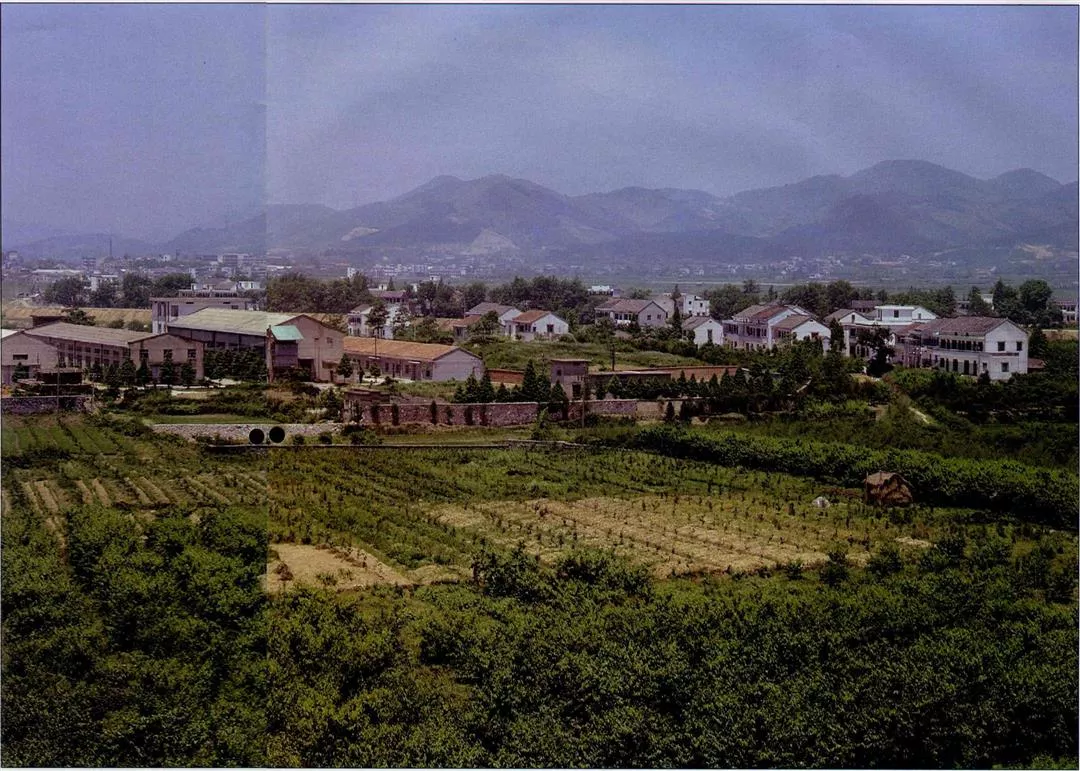

Peach trees, rice paddies, factories, houses. . . a commonplace scene in the Jiangsu-Zhejiang region, and it is the entire view of the Fanshan ruins. Nevertheless, the walled-in field in the center of this picture is where the famous Liangzhu jade was dug up.

Liangzhu Township is far from sparkling with jewels and treasure; the feeling that impresses a person is that of the misty air of this little town in the Jiangsu-Zhejiang region. On either side of the highway over which the bus goes lie unending paddies of rice. At the edge of the paddies are stands of bamboo through which run little brooks; for a visitor arriving from Taiwan, this scene is not strange in the least.

Yet some parts of these fields appear quite different. Aren't a few plots already harvested? Or are they lying fallow? There is dark gray dirt lying obviously exposed and some people standing in it, tilling, no . . . they are digging!

To put it more precisely, they are actually digging up graves; the old tombs hold several Liangzhu artifacts. The world famous Liangzhu jade comes up from the dirt under these rice fields.

In archaeology the definition of Liangzhu culture is completely vague. Its age is between 5300 and 4200 years ago, the same as the Lungshan culture of Shandong, or the ancient cultures of Fujian and Taiwan found at the Daben excavations and at Peinan; all date to the later part of the New Stone Age. Its area of distribution is also very large. From Yuhang County along the border of Zhejiang and Hangzhou all the way to the Taihu region of Jiangsu Province, and from there to the sea coasts in the Jiangsu-Zhejiang region, all played host to this culture.

From the perspective of archaeology, the discovery and new recognition of Liangzhu culture in the remote Yangtze river valley represents the most important breakthrough in recent years for understanding mainland China's prehistoric civilization.

In the past, prehistoric civilization " . . . generally revolved around Lungshan and Yangshao," says Wang Mingda, research assistant at the Archaeological Institute of Zhejiang Province. Most people believe that the origin and center of civilization was in North China. After the excavation of huge numbers of artifacts of the Liangzhu, it was established that the Yangtze river valley, like the Yellow river valley, also held "a very glorious and splendid culture." For a neolithic culture, it was in no way inferior to the north.

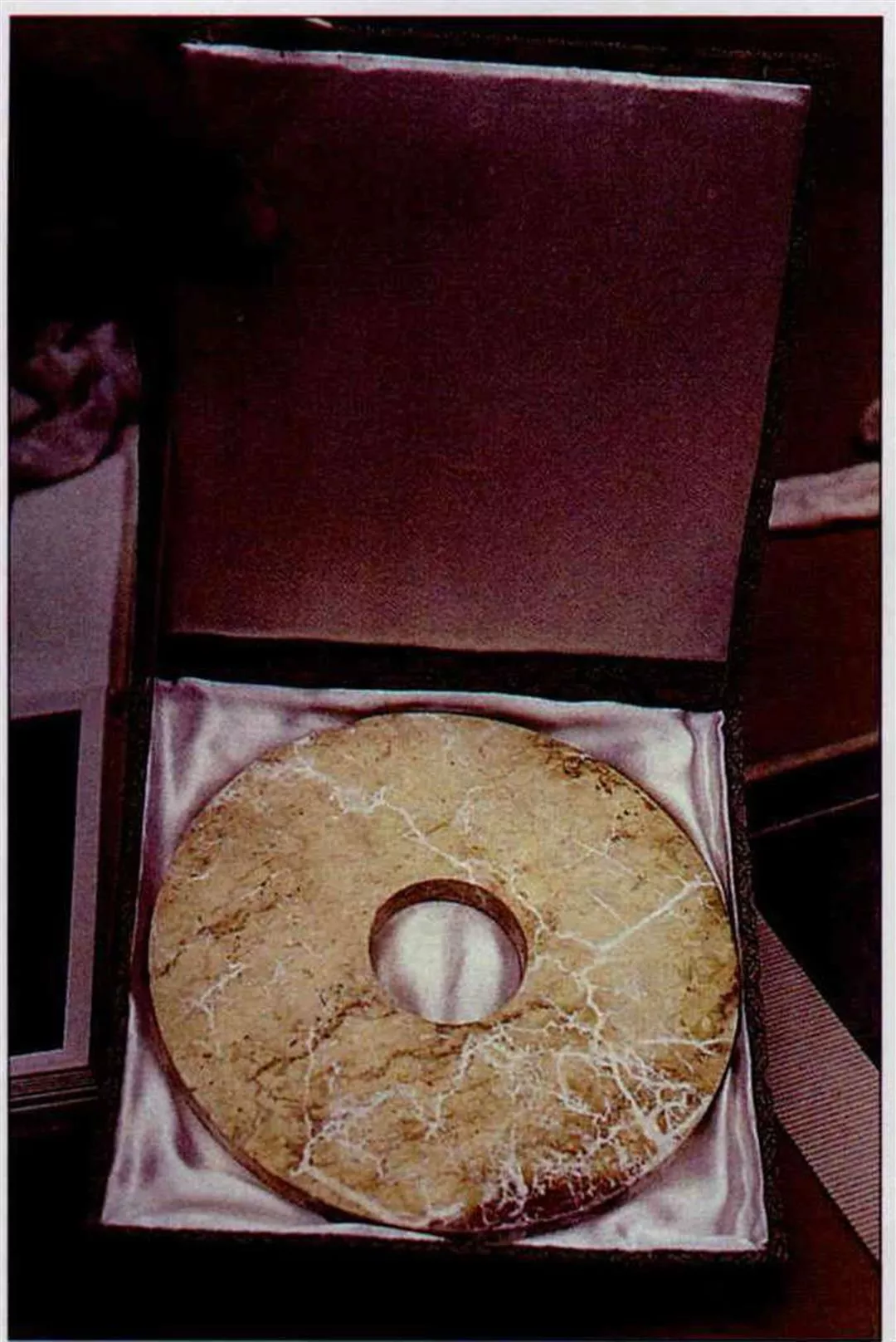

The special characteristic of the Liangzhu pi is its uniform brightness and transparency. Its crafting suggests a relation to such customs as the worship of the heavens, with the warding off of evil, and with ornamental burial of the dead.

Among the unearthed artifacts of the Liangzhu culture, such as rice grain, earthenware dishes, silk, hemp and bamboo implements, was something which proved the advanced accomplishments of the Liangzhu civilization, and brought marvel to the faces of all who beheld it: jade.

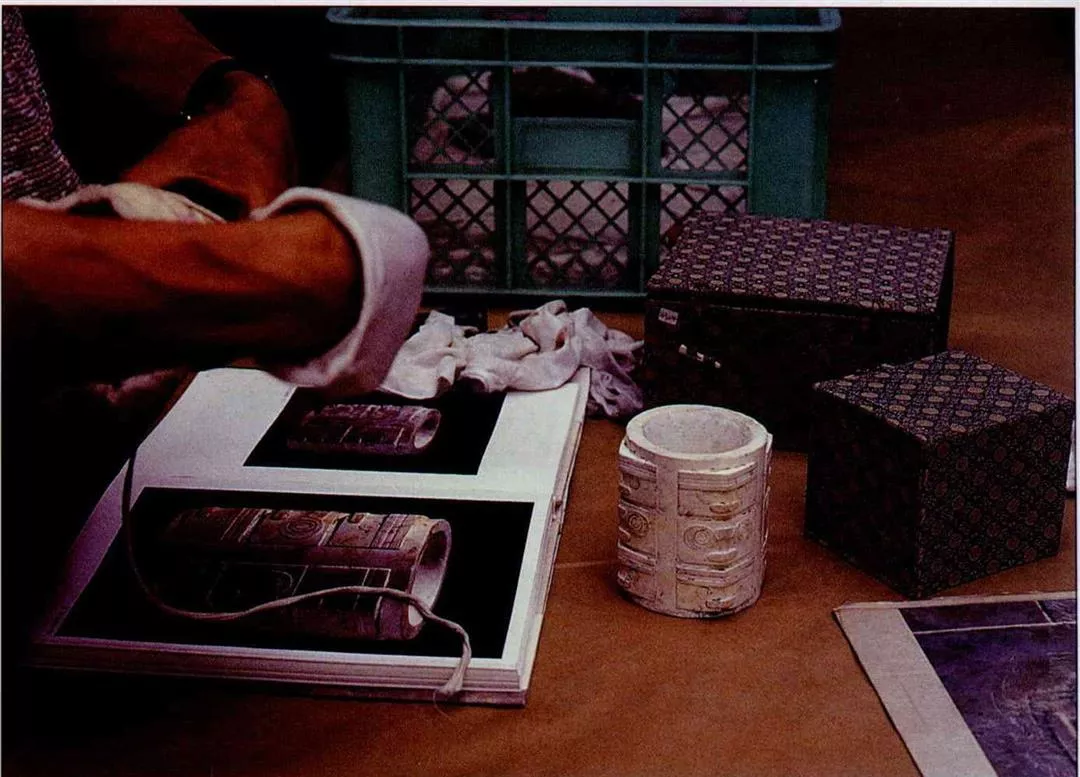

In the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Assistant Researcher of the Archaeological Institute of Zhejiang Province Wang Mingda delicately moves the results of digging in Liangzhu Township: a tsung, a small jade vessel, round on the inside, square on the outside, with a hollowed-out cup-shaped center; a smooth and patternless pi (a flat jade disk with a hole in the center); a jade axe head whose blade is carved in the pattern of clouds and birds. There is more: a jade bracelet shaped like a dragon's head, a jade belt buckle, a life-like jade frog, a jade butterfly, a jade pendant, a tapered jade pike and more. All are typical representational jade objects of the Liangzhu culture.

The color of these pieces of jade, buried for thousands of years in the mud, is not mossy green or ocher, as one might expect; it is milky white, what antique experts term "chicken bone white." Of all the different kinds of jade, the piece that has become the hot topic of discussion is the artifact excavated from Fanshan tomb #12. At a height of 8.8 cm, 17.6 cm in diameter, and weighing 6.5 kg, the "King of Tsung Jade" is rivetingly impressive.

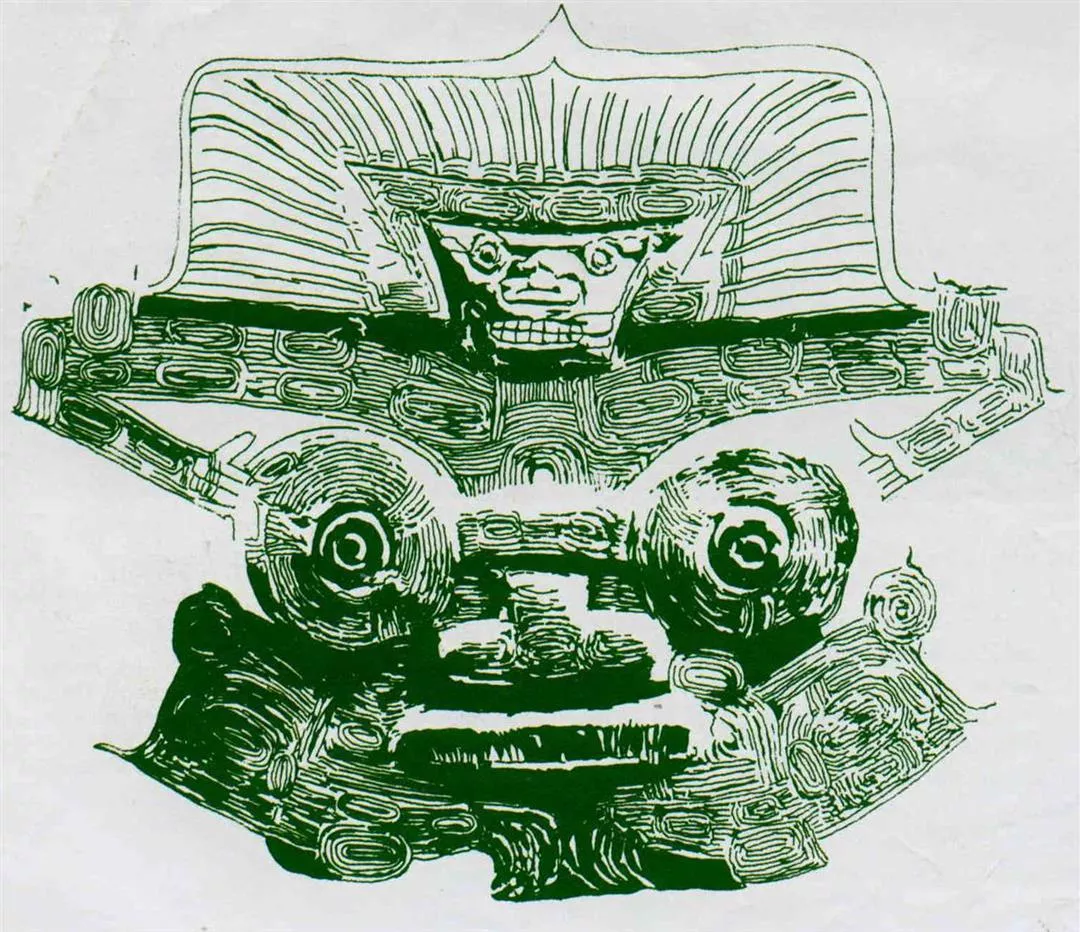

The Chinese love of jade has its own tradition. In the past we all generally believed that the appetite for jade came into vogue during the Hsia, Shang and Chou dynasties. But today archaeological evidence has overthrown yesterday's theories. The many jade objects of the New Stone Age, especially the flood of Liangzhu artifacts, not only prove that the Chinese began to adore jade long before the Hsia, Shang and Chou era; the techniques for fashioning jade that were employed five thousand years ago still draw the admiration of people living today. The"King of Tsung Jade," for example, is divided into four identical sections. Each section has four corners, on which can be seen a pattern of beast faces with eyes composed of multiple concentric circles. In the middle is a lightly carved groove. At the top and bottom of the groove are two reliefs of beast faces, on top of which is the relief of a god's head sporting a feather cap.

In the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, it is not permitted to photograph the precious Liangzhu jade- -at close range. This is the most typical form of Liangzhu jade the tsung. A beast with eyes of concentric circles adorns each of the four corners of this tsung. The ja de stone is translucent.

The pattern of the god is very delicate and complex. One can not view it clearly with the naked eye; a magnifying glass is required. What kind of tool was used to fashion this kind of intricate pattern? How was it carved? Because no carving tools have yet been discovered, this is still a mystery. According to current research, a variety of techniques, such as sawing, cutting, gouging with cogs, grinding, carving, and chiseling, were employed to produce Liangzhu's objects of jade. Many people suspect that at the time there was already a professional jade craft.

Is this evidence of nascent civilization? Or was their civilization already well advanced? Had they even attained a certain system of sovereignty, nationality, and a written form of language? Archaeologist Yang Jianfang of the Chinese University of Hong Kong believes many of the objects, such as the "King of Tsung Jade," disks and axes, are beautifully formed and very large. These kinds of bulky jade objects are not easy to wear as a common decoration. Perhaps they were used as articles of worship.

Archaeologist Chiang Kuang-chi offers this explanation of the tsung: in the Liangzhu era, they already had the position of the so-called "witch doctor," who helped the people communicate with heaven by using the shape of the tsung to symbolize the round sky and the square earth. Perhaps by that time they had already attained a stratified society.

He still believes that from the appearance of the great numbers of Liangzhu jade pieces, the approximate meaning can be inferred from the ancient writing, "In the time of the rulers Hsuan Yuan, Shen Nung and Ho Hsu, stones were used as weapons. In the time of the emperor Huang Ti, jade was used for weapons. In the time of Yu [founder of the Hsia dynasty], bronze was used for weapons . . . ." Ancient Chinese society very possibly developed differently from the West; perhaps between the Stone and Bronze 'Ages, there was a Jade Age.

The most famous of Fanshan artifacts, the "king of Tsung Jade." Carved with miniaturized etching techniques is a tiny god sporting a feather cap. The head wear of this god is similar to that of the buried person. Quite possibly this ornament copies the likeness of the deceased before his death.

Liangzhu jade was first unearthed early on in the 1930s. Wang Mingda points out that at that time the Nanjing-Hangzhou National Highway had just opened up. Situated in Yuhang County, Zhejiang Province, Liangzhu was placed perfectly in the path of the new road. Much of the farmland was dug up for the road, and many jade objects were naturally exhumed. "Ask any old folks in Liangzhu, 70 or 80 years of age, and they all can tell you stories of digging up jade from the dirt in those days," says Wang Mingda.

"At the time the amount dug up was small, so knowledge about Liangzhu was very shallow. Most people presumed it was jade of the Hsia, Shang and Chou. Still others placed it even more recently, during the Han dynasty," says Yang Jianfang.

In the 1970s, many places, such as Caoxie Mountain in Jiangsu and Fuquan Mountain in Shanghai, one after the other uncovered Liangzhu jade that was verified to be from the neolithic period. Originally recognized as a traditional old jade area, Liangzhu was given even greater expectations. Then, from May to October of 1986, the "Fanshan ruins," located in the vicinity of Liangzhu, revealed more than 10 excavation sites. More than 3000 jade objects were disinterred. "It caused a great sensation," says Wang Mingda. Liangzhu jade had cemented its position in the realm of archaeology.

Besides the Fanshan ruins, another important location for Liangzhu jade can be found in Yuhang County--the Yaoshan ruins. In 1987 more than 630 pieces of jade were uncovered there. Of all the relics recovered from these two sites, more than 90% were jade. This amounts to most of the Liangzhu jade found in the Jiangsu region. Because of this the area has drawn many foreign tourists. "After 1988, groups of Taiwanese visitors have arrived by the dozens," says Wang Mingda.

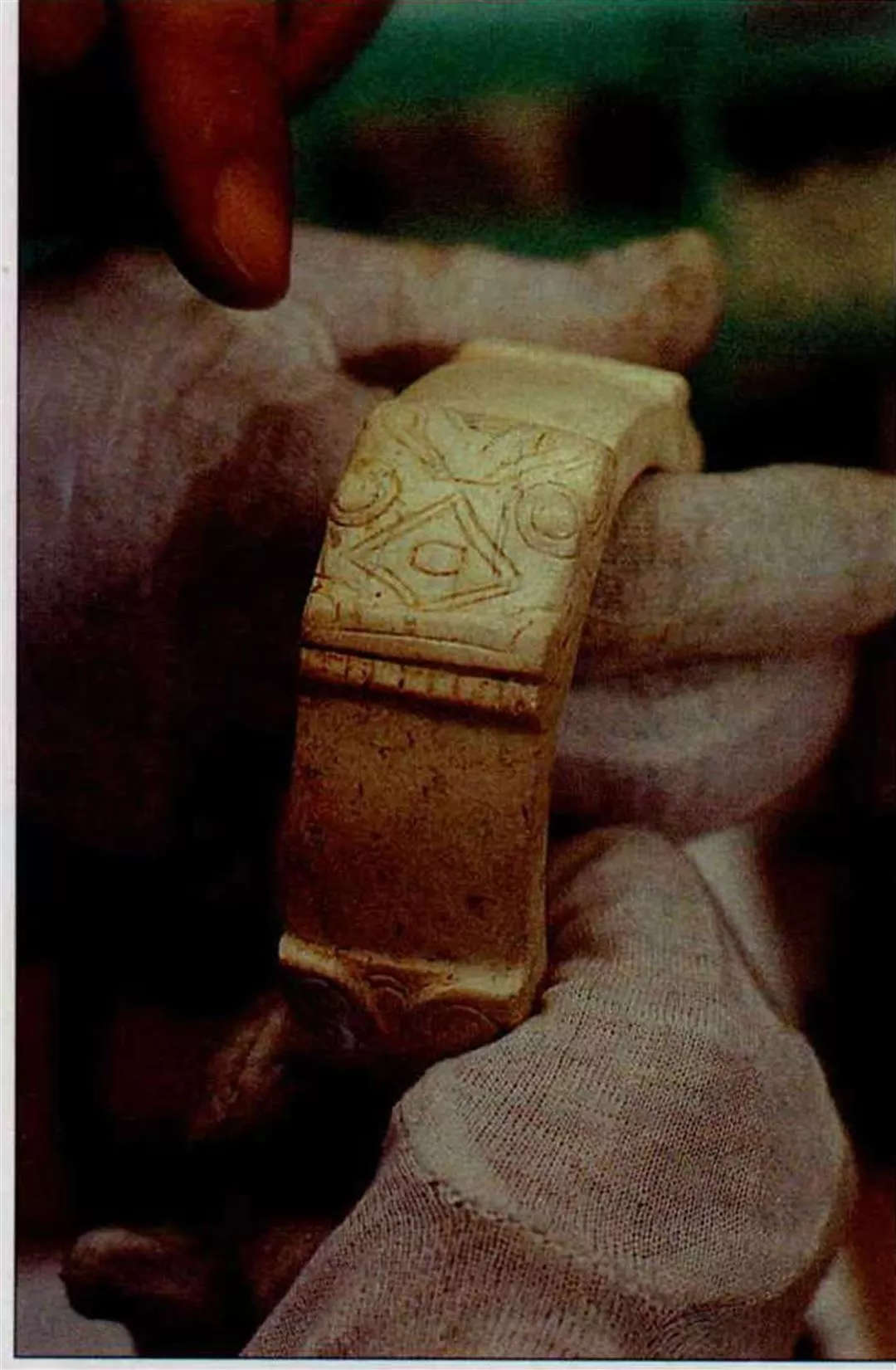

Four dragon heads adorn this bracelet. This pattern, known as Chi-you, appeared from the Hsia to Han dynasties.

As Liangzhu jade has become the focus of everyone's attention, its price has increasingly risen. But this has spawned a number of additional problems, such as robbing and selling off the jade, the notoriety of which can not be stopped.

Thanks to the actions of grave robbers, Yaoshan was hurriedly excavated in 1987. On April 30, 1987, a rumor spread that the old graveyard in Yaoshan held jade. A few thousand peasants gathered together, proceeding to pillage the tombs. It was reported that over 200 tombs were robbed at the time, until several days later, when police arrived to inspect, accompanied with experts on cultural artifacts. Many objects of jade had already gone missing. But after the police asked everyone to return the looted goods, the resulting wave of precious objects was astounding. On the last day for handing in the property, more than 300 pieces of jade appeared, including six tsungs.

According to available data, the Fanshan ruins have one grave site which yielded more than 200 pieces of jade. According to the latest estimates, Yaoshan turned up more than 600 articles. Who knows how many others were lost? Wang Mingda remarks that waiting until the graves were broken open before investigating them is like locking the stable when the horse has been stolen. "ls it so hard to hide little things like antique jade? Anywhere will do--a haystack, a bamboo chair, even a bunch of fruit," says Taiwanese antique collector Jeff Hsu. According to stories floating around Liangzhu Township, many artifacts have disappeared and are floating around unaccounted for. This often produces social problems and crimes, even in the peasant communities, because the treasures are divided unequally, are coveted by people, or are damaged.

Wang Mingda knows one such example. There was one peasant, a "criminal element" who stole a long jade pipe. Afterward, another peasant fell to coveting his pipe, and kidnapped the "criminal," taking him into the wilderness and demanding that he give up the stolen object. The "criminal" refused, and the covetous peasant still had no way of knowing its whereabouts. Finally, the two peasants reached an agreement, and sawed the jade pipe in two, each peasant getting a half to sell. Of course, this sadly resulted in the destruction of the pipe.

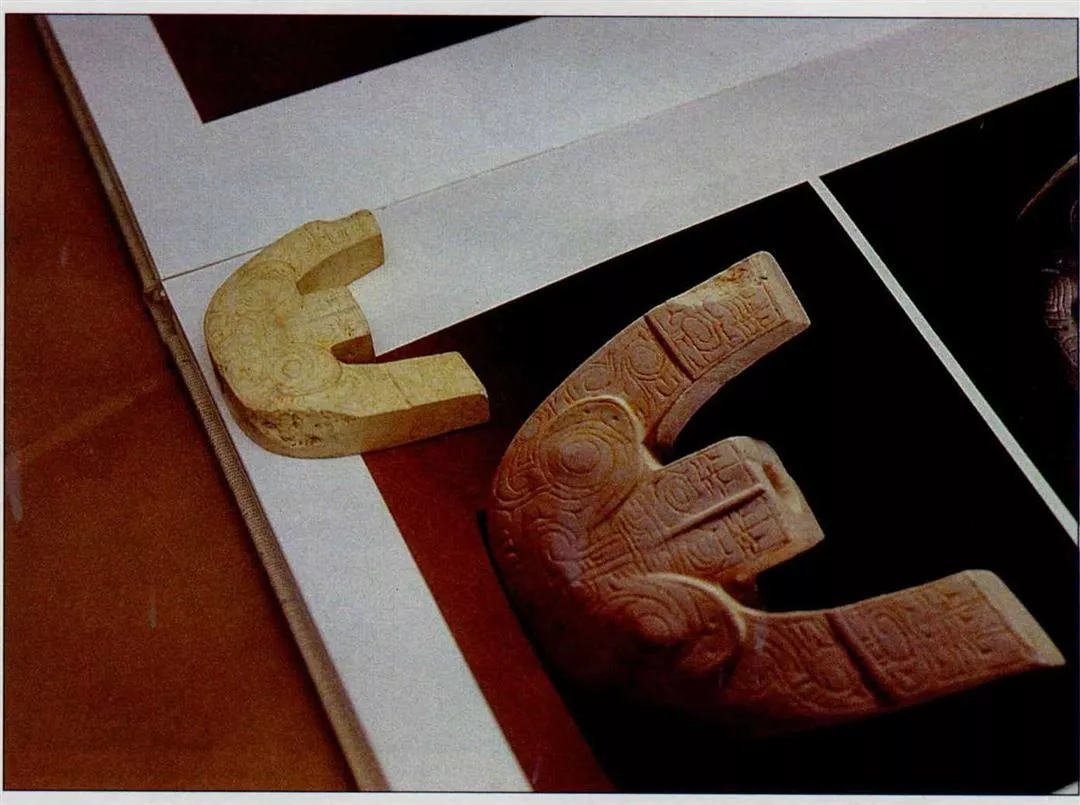

A three-pronged jade object excavated from Yaoshan. The upper part forms the Chinese character for "mountain." A hole has been drilled through the top; very likely this piece was meant to be worn as jewelry.

Among the tales of grave looting in the mainland are stories of robbers who could not move Buddha statues, so they cut off the Buddha's head and carried it away. Similar acts of destruction in Liangzhu are not nearly as awful, but in terms of loss to archaeology, they amount to the same thing. Wang Mingda notes that some of the worst looters made a great mess of the grave site in order to hide the evidence of their theft, to avoid investigation by the authorities. Disturbing the grave site is equally as regrettable as the loss of the objects inside the graves. When relics are discovered without relation to the excavation area and its surrounding environment, their archaeological and historical value is damaged.

"In the midst of today's society that only thinks about money, economic forces are too strong to resist. Actually, we all are its victims." When touching on the issue of Liangzhu jade theft, Wang Mingda's voice takes on a tone of lament. In the past everyone was poor, and not so many people hoarded up relics. When peasants in the fields accidentally shoveled up an object of jade, most would just hand it in to the authorities. With the advent of reforms, the life of the people improved, but their hunger for possessions increased, too," says Wang Mingda, and he recalls that since the economic reforms of 1978, handing in Liangzhu jade is unheard of.

The increased numbers of jade lovers searching the soil has stimulated archaeologists, as well. The extent to which they cherish artifacts and love history is "more than anyone else in the mainland." But putting an emphasis on ancient artifacts requires certain conditions. "You've got to have people and money," Wang Mingda admits, though he does not like to dwell on the subject. All the manpower and money of the Zhejiang archaeological research units is being invested in scrambling to save the ruins being disturbed by construction. There is no time to boast of saving sites and archiving relics. "Piles and piles of research data have been stored away in warehouses, still waiting to be sorted and prepared for publication!"

A tapered pike excavated from Fanshan. The part closest to the bottom is decorated with animal faces.

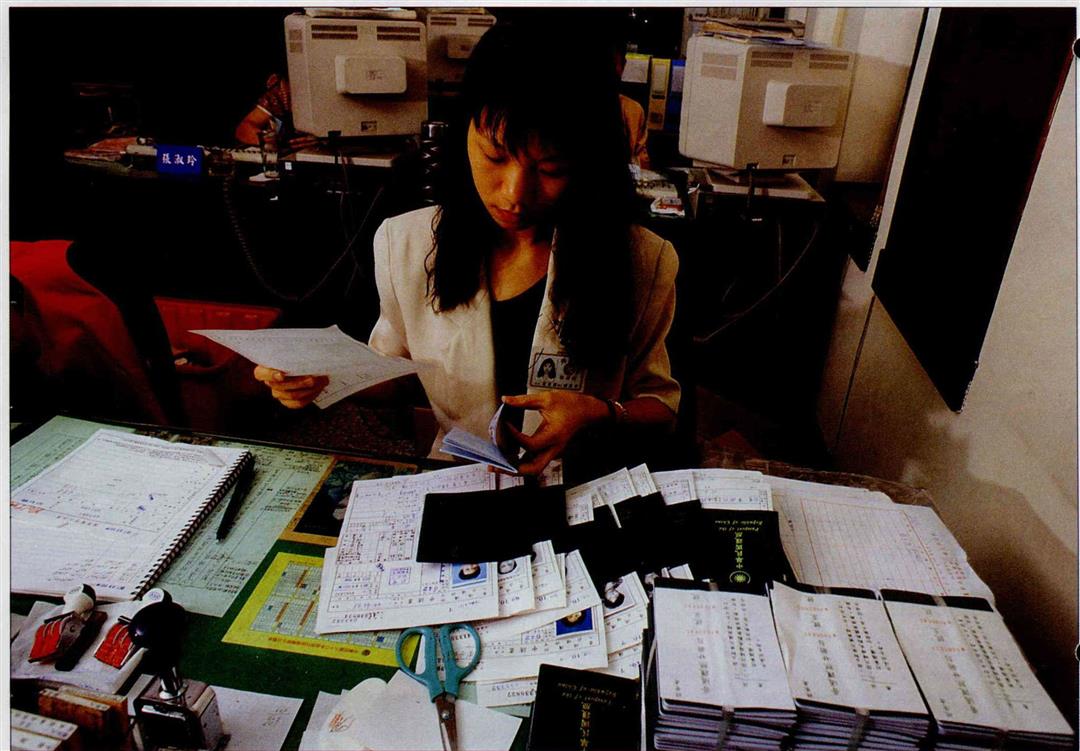

Inside the storehouse of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, the method for saving excavated treasures, such as jade tsungs, is to wrap them up in white cloth, then place them in steel lunch boxes. Compared with the careful, meticulous storage methods of both public and private museums in Taiwan, this manner of collection is certainly crude. Wang Mingda, who has spent many years with these articles, explains with a little embarrassment, "These are still wrapped in the original packings they were put in at the time of excavation. They haven't been organized yet. I'm terribly sorry that we're mistreating the objects of ancient peoples like this."

Perhaps this task can not be accomplished so quickly. But all can rest assured that some day in the future these thousand-year-old treasures of Liangzhu jade will receive the heart-felt care and adoration they deserve, just like all famous ancient pieces of art in the world.

[Picture Caption]

p.47

Peach trees, rice paddies, factories, houses. . . a commonplace scene in the Jiangsu-Zhejiang region, and it is the entire view of the Fanshan ruins. Nevertheless, the walled-in field in the center of this picture is where the famous Liangzhu jade was dug up.

p.48

The special characteristic of the Liangzhu pi is its uniform brightness and transparency. Its crafting suggests a relation to such customs as the worship of the heavens, with the warding off of evil, and with ornamental burial of the dead.

p.48

In the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, it is not permitted to photograph the precious Liangzhu jade- -at close range. This is the most typical form of Liangzhu jade the tsung. A beast with eyes of concentric circles adorns each of the four corners of this tsung. The ja de stone is translucent.

p.48

The most famous of Fanshan artifacts, the "king of Tsung Jade." Carved with miniaturized etching techniques is a tiny god sporting a feather cap. The head wear of this god is similar to that of the buried person. Quite possibly this ornament copies the likeness of the deceased before his death.

p.49

Four dragon heads adorn this bracelet. This pattern, known as Chi-you, appeared from the Hsia to Han dynasties.

p.49

A three-pronged jade object excavated from Yaoshan. The upper part forms the Chinese character for "mountain." A hole has been drilled through the top; very likely this piece was meant to be worn as jewelry.

p.49

A tapered pike excavated from Fanshan. The part closest to the bottom is decorated with animal faces.

p.50

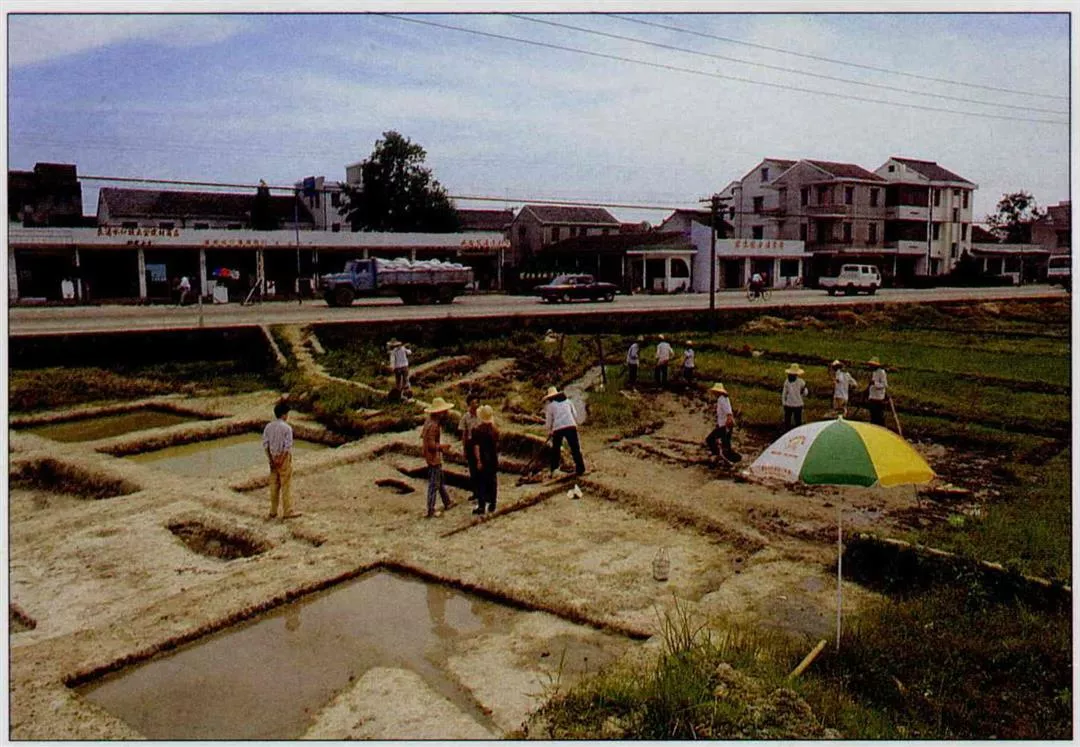

There are still several excavation sites in progress in Liangzhu towns hip. However, when artifacts are being disinterred, outside visitors arenot allowed to approach. Work was already in progress when the photo was taken.

p.51

In front of the house with gray bricks and white walls, the summer ricehas already been harvested. The Jiangsu-Zhejiang region, usually known for its fish and r ice, formerly was not the focus of attention in the realm of archaeology.

p.52

Whenever construction infringes on ancient ruins, work must cease immediately. The major task of the world of mainland archaeology in recent years is to "rescue" such ruins discovered by construction.

p.52

When spring turns into summer in the Yangtze river valley, the peaches are already ripe.

There are still several excavation sites in progress in Liangzhu towns hip. However, when artifacts are being disinterred, outside visitors arenot allowed to approach. Work was already in progress when the photo was taken.

In front of the house with gray bricks and white walls, the summer ricehas already been harvested. The Jiangsu-Zhejiang region, usually known for its fish and r ice, formerly was not the focus of attention in the realm of archaeology.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)