Now that CITES has placed the tiger on the list of protected species, and the ROC's Council of Agriculture has forbidden the country's citizens to use tiger bones and other tiger products, in the future the tiger will effectively disappear from many Chinese people's lives; but the tiger's image will not fade from Chinese people's spiritual lives. Cao Zhenfeng, vice-director of mainland China's Museum of Chinese Art, even says: "The Chinese are not only the children of the dragon, but even more so the children of the tiger." Why is that?

The story goes that when Wu Sung came out of the inn, the first thing he saw was four hunters running helter-skelter down the road. When Wu stopped them and asked what they were running from, one of them explained: "The emperor has put up a reward for catching a tiger, and we went to try and catch it. But the tiger came down from the mountain and chased us instead. It was so fierce that we ran all the way here." On hearing these words, Wu Sung's face darkened into a frown, and he said: "Surely you know that hunting tigers is forbidden under international conservation agreements?"

Why this distortion of the episode "Wu Sung Kills a Tiger" from the epic Chinese novel The Water Margin? In fact, this is a new version of the Wu Sung story, created by Taiwan University's glovepuppet theater group the Se Den Society, and performed for the celebration last month of the society's ninth anniversary. In the new play, Wu Sung has become a conservationist. Although roaring drunk, he is clear-headed enough to give the hunters a dressing-down and a lecture about environmental protection, and when he catches up with the fierce tiger on Chingyang Ridge, Wu spares its life. After telling the tiger not to hurt humans any more, Wu Sung strides back down the mountain with his head held high and his chest thrust out.

Ever since the year before last, when an international conservation group released a video film showing people from Taiwan killing a tiger, in many foreigners' eyes the only association between tigers and the Chinese has been their killing tigers, eating their meat, skinning them and cutting off their penises. Eager to make amends, the theater group transformed the tale of Wu Sung barehandedly killing a tiger-which is as familiar to Chinese people as the story of "Great-Aunt Tigress" (who bites off the fingers of children who cry)--into one of Wu Sung "letting the tiger return to the mountain."' In this way they sought to warn modern Chinese to no longer be so enthusiastic about seeing the "tiger-slayer" as an image of Chinese heroism.

But in fact Chinese people's relationship with tigers was never only one of enmity or of seeing them as a resource to be exploited.

Although tigers are not unique to China, a million-year-old fossilized tiger skeleton which paleobiologists have found in southern China is the most primitive known tiger, and the ancestor of modern tigers. Biologists believe tigers originated in southern China, from where they radiated out in all directions and finally evolved into the eight distinct Asian subspecies.

Paralleling this biological discovery, researchers studying the origins of culture have also found evidence to indicate that even back in the tribal period of remote antiquity, people shared a community of fate with tigers.

According to written records, the tiger was worshipped as a totem by early nomadic herdsmen of the ancient Qiang tribe. In their search for lusher pastures, the Qiang became the first people to enter China's central plains, and 6000 years ago some Qiang people who followed the Yangtze downriver created the Liangzhu culture in what is now Zhe-jiang Province.

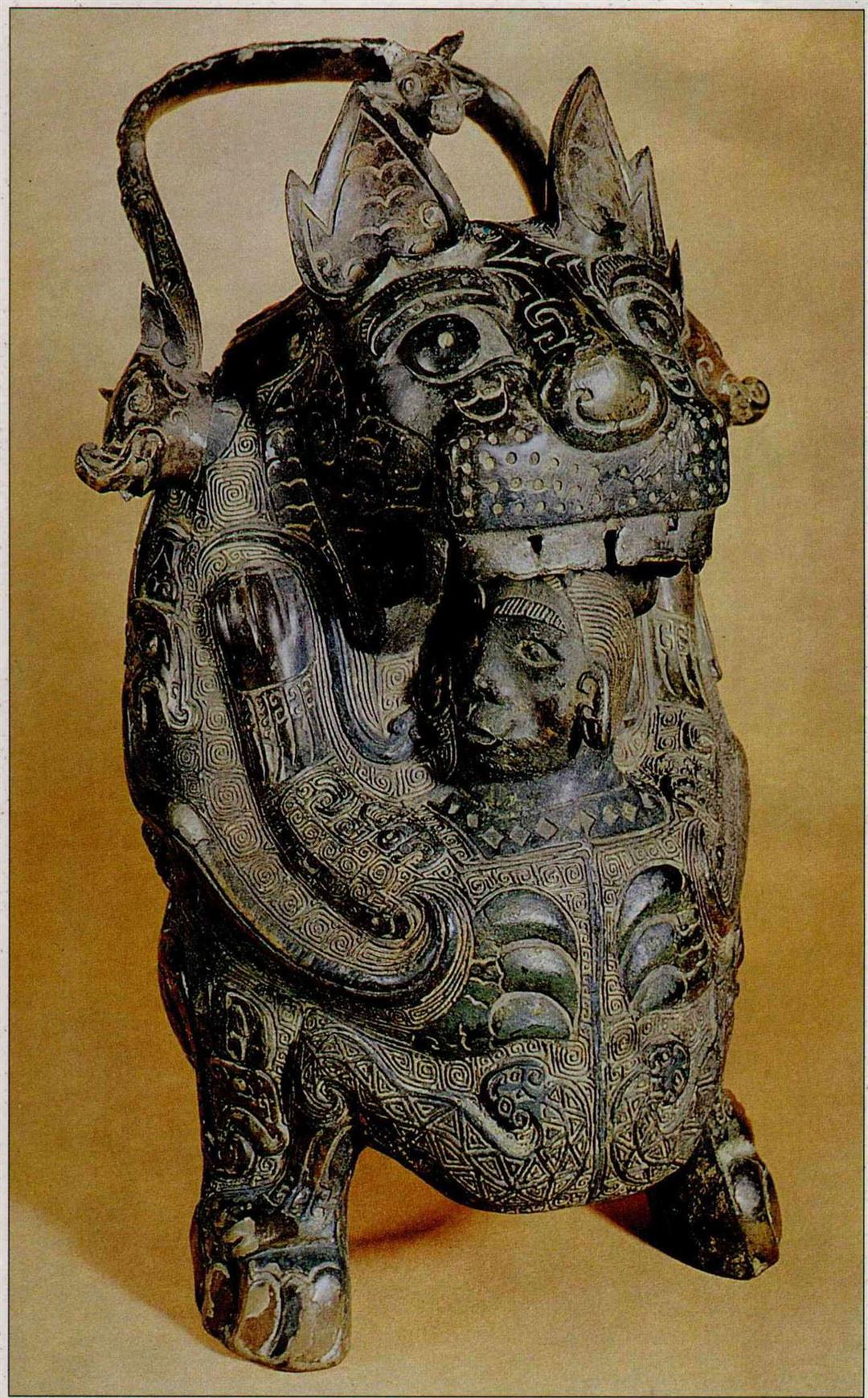

Ancient artifacts and utensils unearthed within China today are often richly decorated with tiger motifs, and tiger images are very easy to find among the many articles of Shang and Chou dynasty bronzeware which have found their way overseas. The Western Chou bronze tiger tsun (drinking cup) in the collection of America's Freer Art Gallery is one example. And countless jade tigers and tiger amulets have survived from the Warring States period and the Chin dynasty over 2000 years ago.

Chien Sung-tsun, a researcher of ancient artifacts and executive editor of The National Palace Museum Monthly of Chinese Art, says that the tiger is indeed one of the more commonly appearing animal motifs on ancient Chinese artifacts. Besides the fact that China was one of the main areas in which the tiger lived, more importantly the tiger was the largest and fiercest animal found within China, and the undisputed king of China's jungles. Compared with the bear, the more abundant tiger faded in and out of the forests in ghostly fashion, and was quicker and more agile in its movements. As for the lion, another source of traditional folk motifs for the Chinese, it was an "immigrant" which came into China's mythology in the wake of Buddhism. Because the ferocious tiger was the animal most likely to threaten ordinary people in their real lives, it became one of the most important spirits in which the Chinese believed.

In the earliest days, mankind's power to fend off natural dangers was very weak, and people were terrified of the strength and ferocity of the tiger. This fear gave rise to respect, and a certain degree of mystification. The stone carvings and bronzeware of the Shang and Chou dynasties all emphasize the tiger's sharp claws and fierce countenance. "At the dawn of civilization, this was humankind's main impression of the tiger," believes Lin Po-ting, curator of painting and calligraphy at the National Palace Museum.

But more interestingly for us today, the tiger culture which sprang from this early totem worship continued to developed with Chinese society over the ages, always appearing in new guises.

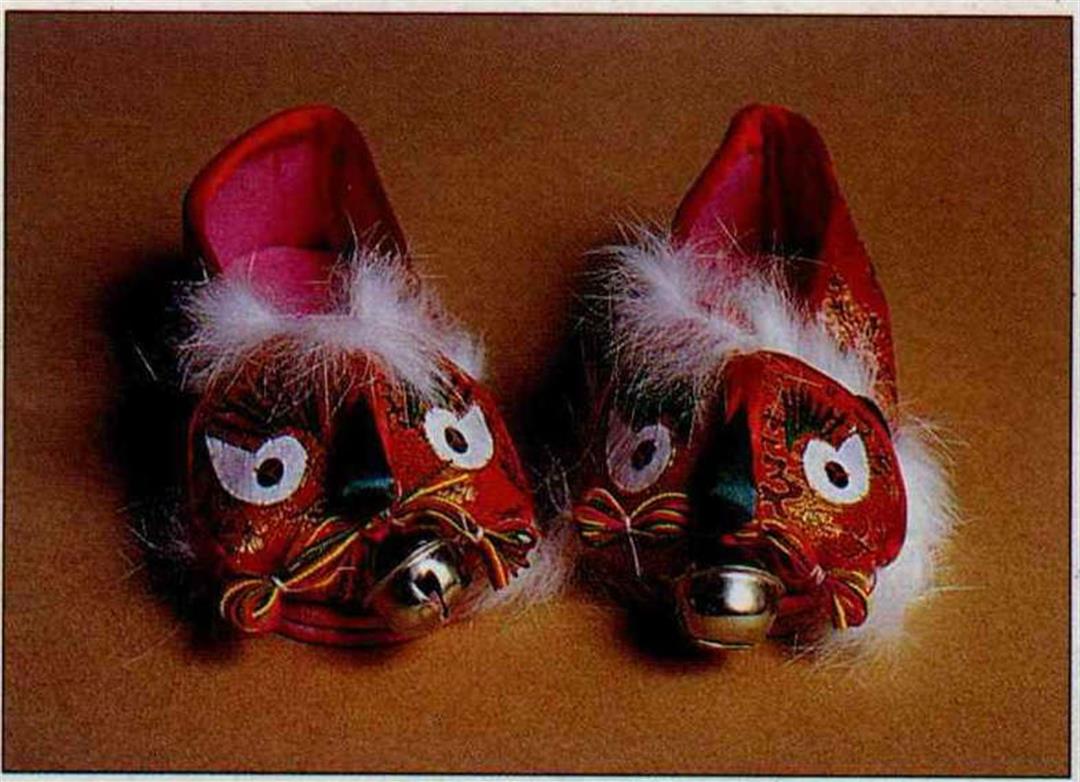

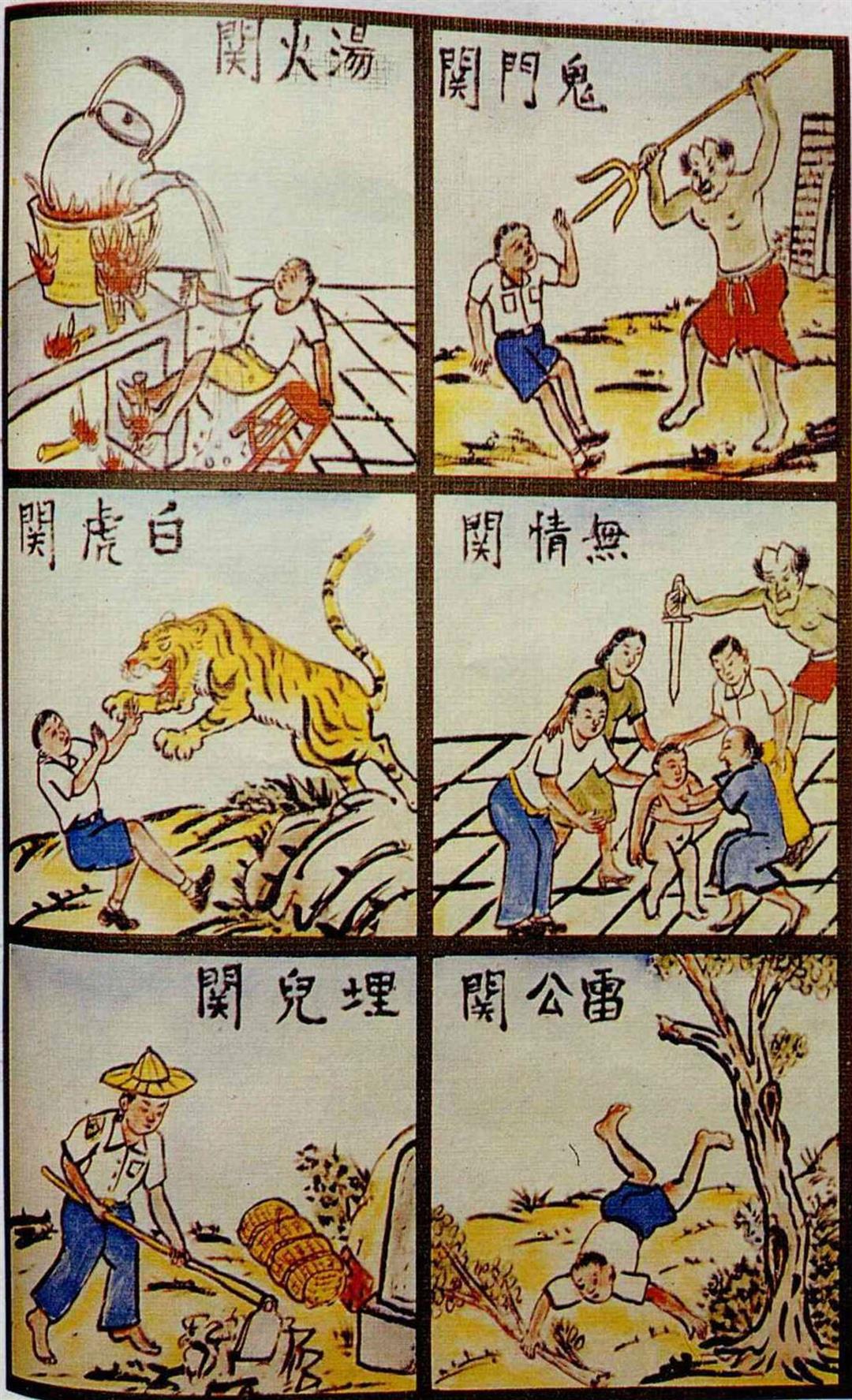

From a totem of old tribal society to a folk symbol to bring good fortune and drive out evil, the tiger is not only the fiercest animal in China's jungles--its images is found everywhere in Chinese people's lives. (picture at left courtesy of Weng Ching-huo)

Cao Zhenfeng notes that in early times tiger spirits were worshipped as the masters of the universe, all living things and the lives of human beings. Among the tribes of the Shang dynasty, the tiger was credited with powers on a par with those of the dragon to ascend to the highest heavens, bring good fortune and drive out evil.

Scholars at Anyang museum in mainland China believe that the taotie patterns (the taotie is a ferocious and gluttonous mythical beast) on Shang and Chou dynasty bronzeware, which express the mystical power of nature, heaven and earth, "could be dragons or could just as well be tigers." But when China entered the agricultural age, farming made people more and more dependent on nature with all its vagaries, and the tiger's status was gradually usurped by the more abstract dragon. Thus the dragon and tiger became separated.

From the Chin dynasty onwards especially, the dragon was monopolized by the royal family and became the embodiment of the emperor and the symbol of his power. From this time on the dragon was elevated to a heavenly status, while the tiger found its home among the people.

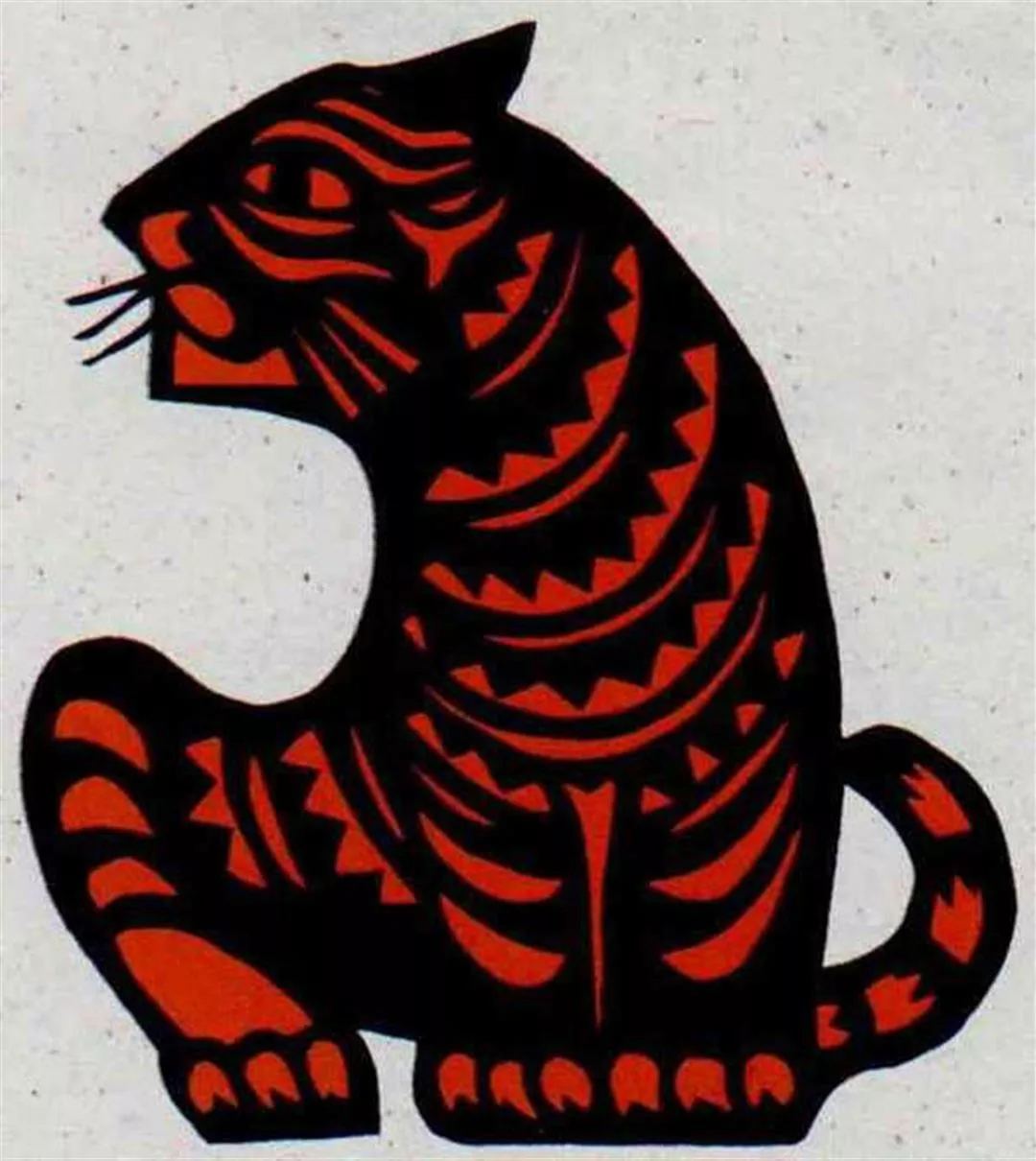

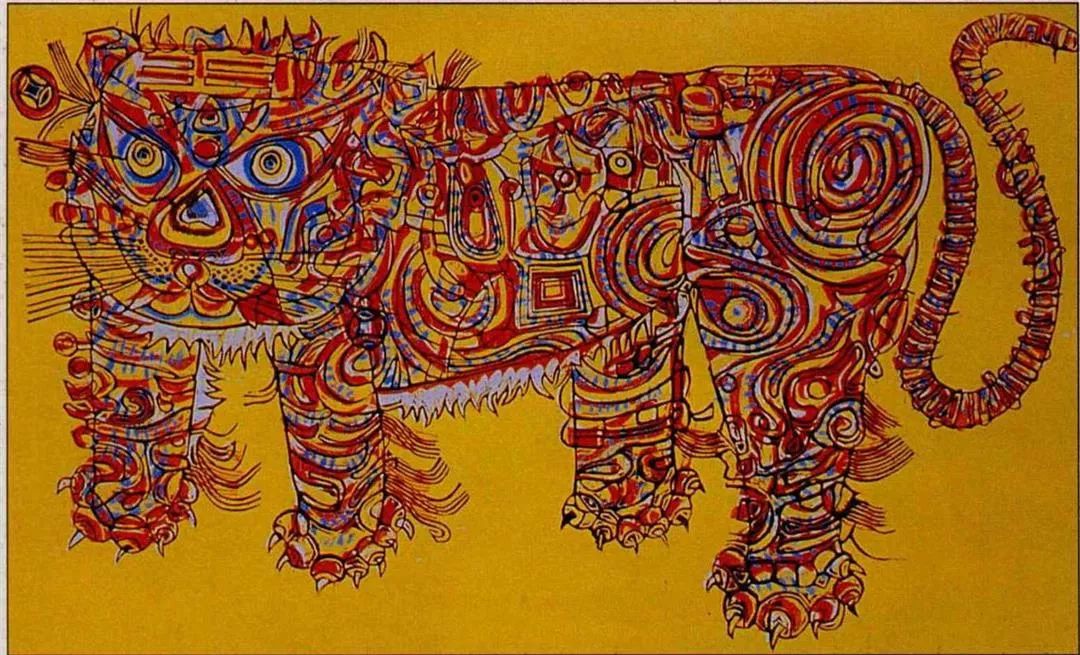

But although this struggle between the dragon and the tiger ended with the tiger spirit being cast down into the world of men, this was not the end of its career, for the practice of creating tiger images spread throughout the people and continued down the ages. In Chinese people's daily lives and in their rituals, the tiger became an object of artistic appreciation, and its representation gradually developed from a ferocious beast into the cuddly, buffoonish tiger of folk art. "In this sense, tiger culture actually progressed," opines Cao Zhenfeng.

In the mainland countryside today, one can still see children wearing tiger-head shoes, tiger-head bibs, tiger-head caps and tiger-head gloves made by their mothers, and holding tiger-head cloth toys and sleeping on tiger-head pillows.

In China, no other animal is as widely seen in people's everyday lives as the tiger of folk art. From Shaanxi in the north to Hui'an in Fujian Province in the south, or among the minority peoples of Yunnan, folk art tigers redolent with natural, unaffected emotion can be found everywhere. "The ori gins of these folk craft products, which are both useful and artistic, lie mainly in the tiger-head designs on the bronze helmets, armor and bronze battleaxes of Shang and Chou dynasty soldiers," observes Cao Zhenfeng.

As farmland expanded and hunting methods advanced, later generations viewed the tiger differently from earlier ones. On Shang dynasty bronzeware, the tiger always had an air of mystique: pictured at left is a Shang utensil decorated with the image of a tiger eating a man. In the Han dynasty fresco of a hunting party, at right, the tiger has become the quarry in the chase. (courtesy of National Palace Museum)

The tiger's significance as a totem was taken up by the common people, and throughout China it developed into a symbol which was believed to drive out evil and demons and to bring good fortune.

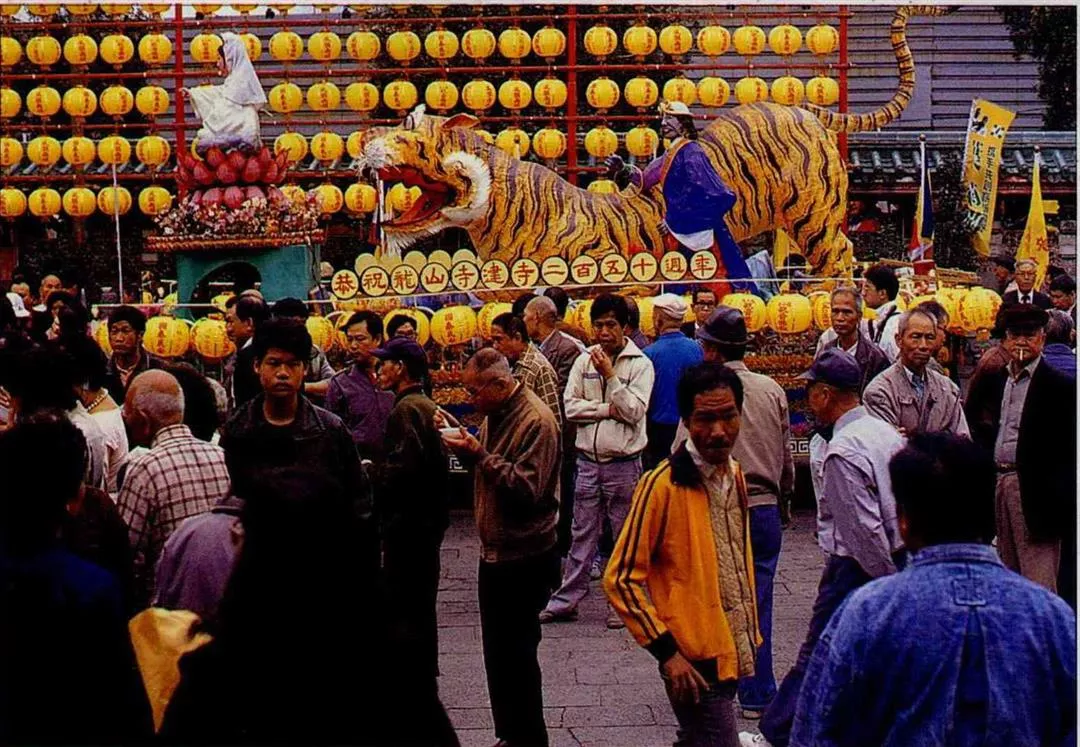

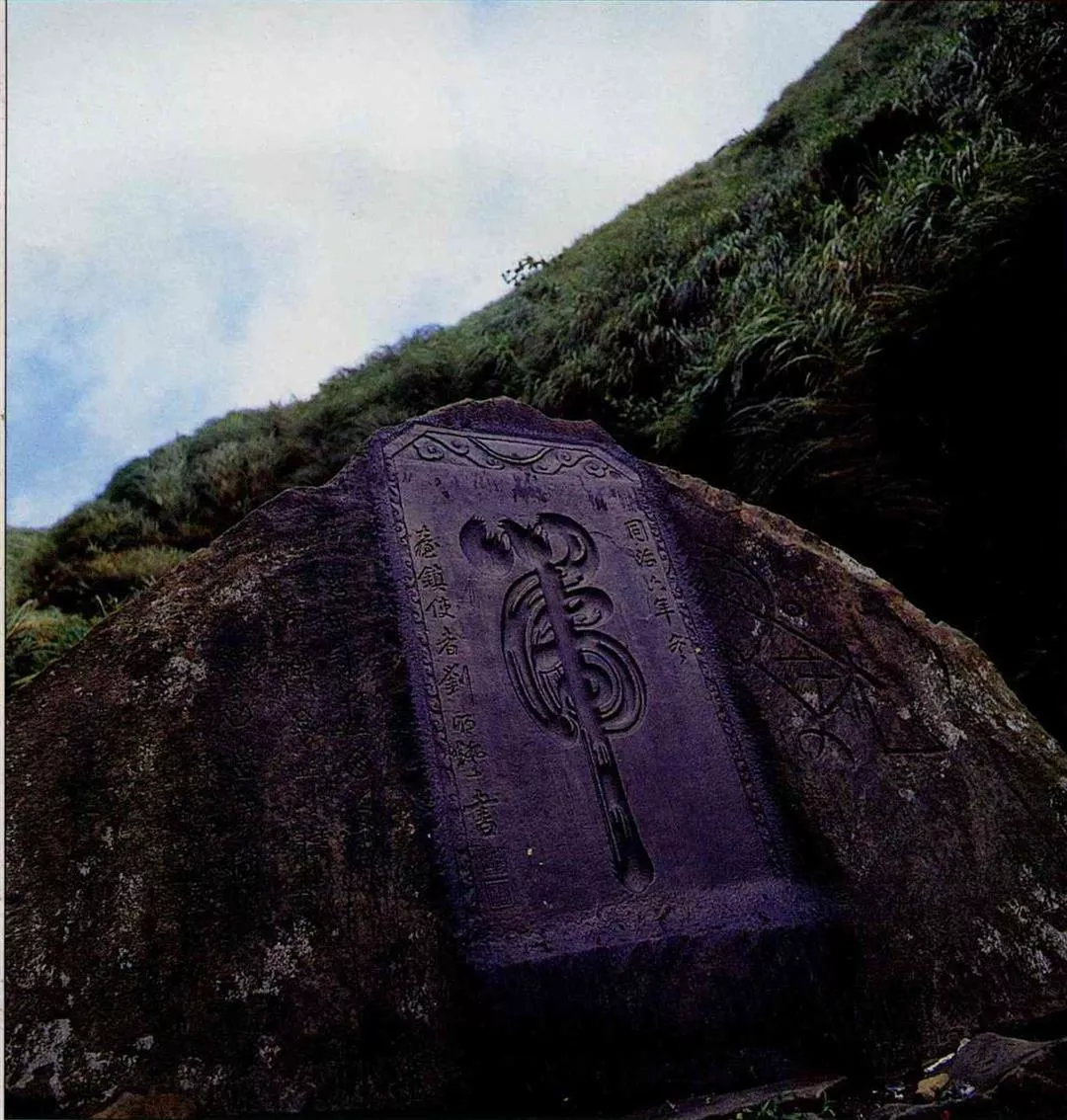

To this day, China has maintained the age-old customs at the Dragon Boat Festival of hanging up a tiger braided from Chinese mugwort, and painting the character 王 (wang, "king"), representing the tiger, on children's' foreheads to protect them from evil. In times past, if a locality was turbulent, a stele with the character 虎 (hu, "tiger") would be erected to pacify the evil influence. The nearest example is on the old Tsaoling military road in the northeast corner of Taiwan, where there is a stele with the character hu written by the Ching dynasty general Chen Liang-kuang. The tiger was often also painted on doors as a door god to drive away evil spirits, and Lungshan Temple in Wanhua, a favorite with tourists, has a dragon and a tiger wall standing next to each other as guardian spirits.

After the lion found its way into Chinese mythology, it usurped some of the tiger's functions For instance, "wind lions" traditionally protect houses from evil spirits. "But in fact previously this kind of role had always been played by tigers," remarks Yuan Chang-rue, curator of the anthropology department at Taiwan Provincial Museum.

The tiger is not absent from Taiwan's folk culture either. At a time of international accusations that more than half the Chinese herbal medicine shops in Taiwan sell tiger bones, very few people know that the most widely revered animal spirit in Taiwanese folk beliefs is Huyeh, an incarnation of the tiger. According to surveys by scholars of folk customs, 70% of temples in Taiwan contain Huyeh images. This is because the spirits most widely revered by the people of Taiwan--Fu Teh Cheng Shen (the Spirit of Happiness and Virtue), Pao Sheng Ta Ti (the Emperor Protector of Life) and Tsai Shen Yeh (the Spirit of Wealth)--all ride on the backs of fierce tigers or sit on tiger thrones. In all these spirits' temples, Huyeh figures are found below the spirit niche. Some believe that this is because temples are places where the spirits of the world of light gather, and Huyeh has the power to subdue the ghosts and demons of the underground world of darkness. Hence he is also called "the general below the altar."

Huyeh is also seen as a guardian spirit of fisher folk. As a servant of Pao Sheng Ta Ti, the "black tiger general" also has the power to cure abscesses and drive out fevers, while the Huyehs in Earth God temples are reputed to banish fevers and keep peace in the temple. It is also said that if children with mumps stroke the tiger's cheeks they will be cured. The folk artisans who carve the Huyeh figures usually give them a lovable appearance so that children will not be afraid to touch their faces. Because Huyeh is often seen beside Chao Kung-ming, the martial spirit of wealth, many gamblers who bet on lotteries such as Tachiale or Liuhetsai also pray to Huyeh. It is said that when Feng Fei-fei had just started out on her singing career, she prayed to Huyeh at Keelung's Hsin Yi Tang Temple, and not long afterwards rose to stardom.

Whether in the form of the tiger motifs on seasonal objects at the Chinese New Year and on traditional decorations, the folk craft products to be found in villages all over mainland China, or the all-powerful Huyehs of Taiwan's temples, these tigers all share the significance of transmitting an ancient national symbol. The same patterns decorate artifacts from the Liangzhu culture of 6000 years ago and the Shang and Chou dynasties of 3000 years ago, and have been passed down to the present day through all the tribal migrations, fusions and conflicts of history. For instance, today's scholars of folk culture trace the custom of praying to Huyeh back to the rural rites of the Chou dynasty . After the harvest was completed, the Son of Heaven would report to eight kinds of spirits, of which the fifth were the cats and tigers, for they protected crops by eating the rodents and wild animals which might damage the seedlings.

Even today, the tiger's status still counterbalances that of the dragon. The expression "as alive as dragons and tigers" describes people brimming with vitality, while "fighting like dragons and tigers" describes a pitched battle between evenly matched foes; in basketball tall players are nicknamed "heavenly dragons," and short players "earthly tigers"; on TV there is the variety show Big Brother Dragon and Little Brother Tiger; the Sung dynasty judge Pao Ching-tien had both a dragon-head guillotine and a tiger-head guillotine to behead miscreants of royal blood; in Buddhism there are arhats to defeat both dragons and tigers; while among the 12 animals ot the Chinese zodiac, the tiger comes before the dragon. Thus it is hardly surprising if one scholar sees the Chinese as not only the children of the dragon, but also of the tiger.

But although the tiger, which is a genuine part of Chinese people's lives, has been elevated on the spiritual plane to an object of folk veneration and belief, unlike the dragon the tiger is also killed for its bones as medicine, and its other organs are indiscriminately taken to be eaten as tonics. This has given many people of other nations a mistaken impression of Chinese medicinal culture. Why should there be such a discrepancy between Chinese people's treatment of the tiger on the spiritual plane and in real life?

In an outspoken article, Cao Zhenfeng has written: "In China's history, there has been a contradictory conception of the tiger. It has been both feared and venerated, both hunted and worshipped. The tiger was both a portent of disaster and an omen of good fortune.... No other animal in Chinese culture is such a blatantly contradictory amalgamation."

In fact there is nothing strange about our contradictory attitudes towards the tiger. They are the product of many wild animals' and mankind's having evolved together since before the dawn of civilization.

When Lungshan Temple in Wanhua celebrated its 250th birthday, this tiger float added to the excitement. (Sinorama file photo)

Chen Wang-heng, author of the book Fierce and Stern Beauty--Chinese Bronze Art, observes that in primitive society, because humans lacked the physical strength to overpower animals such as tigers, bears and panthers, they did their best to avoid them, and did not usually treat them as a major source of food.

But in hunting and fishing society with its low productivity, faced with the harsh realities of nature and a lack of material resources, people gradually extended the range of resources they could use. For instance, the Oroqen people of northeast China once had a taboo against eating bears and tigers, but gradually came to eat bear meat and use bear skins for clothing. But a people which faces the constant threat of death and hunger both needs animals and fears them, and this has given rise to many hunters' taboos. Today, the Oroqen still do not eat bears' heads, and do not refer to tigers directly by name, instead using respectful titles such as Official, Grandfather or Spirit.

As humanity gradually became more enlightened, people came to understand that diseases were not inexplicable punishments meted out by heaven, but could be cured by human effort. Thus Shennung (the reputed inventor of Chinese herbal medicine) tasted all kinds of plants, seeking medicinal materials from throughout nature. In the past tigers were abundant -- the ancient Compendium of Materia Medica records in its entry on the tiger: "We need not record their source, for they are many, and can be found wherever there are mountain forests." In an age when there was no fresh milk to drink and people lacked adequate sources of calcium, there was nothing wrong in using tiger bones as a medicine to strengthen the bones and tendons. But the same practice cannot be carried on today, when tigers' numbers have fallen dramatically. Just a few years ago, mainland China, Korea and Taiwan were all still producing so-called "Quince and Tiger Bone Wine," providing an obvious target for international criticism.

But the main culprits behind the growing mismatch between myth and reality for the tiger have been the invention of tools, advances in hunting techniques, and the growing areas of land cleared for agriculture, which have little by little turned tigers into the victims. As an ancient poet wrote: "Though ferocious, the tiger is lovable/He only runs wild deep in the mountains." But the mountain areas in which the tiger reigns supreme are growing ever smaller.

Lin Po-ting points out that in the hunting scenes which decorate artifacts from the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, one often sees mounted swordsmen fighting tigers, with the tigers in the role of the pursued. It would appear that people's fear of tigers had already lessened considerably since the Shang dynasty, when tigers were often represented eating humans.

How will my luck be this year? Watch out for the white tiger gate--it's as dangerous as the gates of hell. (photo by Yang Wen-ching)

As humans gradually cast off their fear of tigers, they became able to appreciate the tiger on equal terms. The tiger's powerful physique, its lithe, graceful movements and beautiful pelt inspired the splendid tiger patterns we still see today in folk art. However, the secularized tiger in China with its enormous area and complex ethnic mix naturally gave rise to a multiplicity of different symbolisms, creating apparent contradictions. This is no different from the imaginary dragon, for although the dragon is said to be holy and inviolable for the Chinese, there are also some stories of evil dragons. Furthermore, compared with the mythical dragon and phoenix, in the past when tigers were common in China, incidents of tigers eating people or people killing tigers occurred frequently, so that humans' conflicting emotions of both hating and worshipping tigers were very much a reality. Thus although people use folk art tiger motifs to protect children, others have used the tiger as the inspiration for such stories as "Great-Aunt Tigress" to frighten children.

Writers love to use others as the channel for their own ideas, and in Chinese literature there is the hair-raising Encounter With a Tiger, but also the tiger-praising Story of a Grateful Tiger. One can admire the tiger's might and vigor, or use it to satirize many aspects of human life. Among the numerous idiomatic phrases and literary allusions involving tigers, "a tiger father doesn't have dogs for sons" ("a talented father will not have a lackluster son") is laudatory, while "rearing a tiger brings calamity" ("appeasement courts disaster:), "bargaining with a tiger for his coat" ("asking an evil person to act against their own interests"), or "a sheep in a tiger's coat" ("a sheep in wolf's clothing") all point to the evil side of tigers.

The new mayor of Taipei City, Chen Shui-bian, has appointed lieutenant-general Li Tsuo-fu as director of the city's Department of Military Service, because of his reputation for fair and upright dealing while in the army, which earned him the nickname "the Tiger." But since ancient times the Chinese have also had the saying that "powerful people are as changeable as tigers," implying that the actions of the powerful are as unpredictable as the patterns on tigers' coat are variable. Wei Chuang (c. 836-910) of the Tang dynasty wrote in his Tracks of the Tiger: "His white brow often comes to the door by night/His tracks crowd the water's edge/Today I withdrew to a mountain cave/But how is it that there I saw you again, lord?" Here, the tiger is a metaphor for an evil lord.

Apart from being feared, respected, and even used to fight fire with fire by scaring away ill fortune, the tiger is sometimes also avoided as taboo. In Hsiao Li-hung's novel Water and Moon of a Thousand Rivers, the main female character Chen-kuan's aunt tells her: "When you're grown up, you'll wish you weren't born in the year of the tiger. The tiger's a special birth sign; whenever anyone in the family gets married, you'll have to keep away."

Yuan Chang-rue comments that when humans exploit a natural resource they exploit it to the full, and not just in one way alone. On the spiritual plane, the tiger is pressed into all kinds of roles, and its powers in real life are naturally often exaggerated too.

Today's society is even more complex, and the powers ascribed to the tiger have also become more diverse. As people's understanding of nature has increased, the tiger has lost its mystique, and with so few tigers left there is no longer any likelihood of people finding themselves in a face-to-face struggle with a tiger. Thus people are free to develop their own human perspective and let the tiger symbolize whatever they want it to. Some people think Huyeh will bring money and wealth in through the door gripped between his teeth, and therefore represents the god of wealth; for this reason even casinos and restaurants have started praying to Huyeh; meanwhile quack doctors credit tiger penises with the power to confer remarkable virility, when in fact the reference works of Chinese herbal medicine make no mention whatsoever of tiger penises' having any effect on potency.

Chinese people's faith in the curative powers of the tiger has led to many misunderstandings when international conservation groups have accused us of illegally using tiger bones. At a time when only a few thousand tigers remain alive worldwide, the Earth Island environmental group claimed that Taiwan was awash with tiger bones. In fact, even before the use of tiger bones was banned, the number of real tiger bones in herbal medicine shops was probably less than 5%, for "tiger bone" is just the name of a medicine--the bones most commonly sold on Taiwan's tiger bone market are sheep bones. Professor Chang Hsien-che of China Medical College says that this is not trickery on the part of herbal medicine merchants, for Chinese medicine recognizes two categories of "tiger bone": the first is "true tiger bone," which includes tiger, panther and lion bones, and the second is "sundry bones," which includes cattle, horse, pig and dog bones. Both categories are sold in the herbal medicine shops, at different prices. The reason they are all called "tiger bone" is because "tiger bone" sounds much more efficacious than "pig bone" or "dog bone," just as in Chinese medicine there is also the so-called "white tiger," which in fact is a plant and has nothing to do with tigers at all.

Unfortunately foreigners do not understand these subtleties, and think that all the bones on show are tiger bones. Today, the Department of Health has no choice but to call on medicine merchants to respond to the situation by calling the "sundry bones" by their rightful names.

Most Chinese remedies are composite concoctions. "Quince and Tiger Bone Wine" contains a dozen or more ingredients, but the active one is not really tiger bone, for Chinese herbalists have since discovered much more effective tonics for the bones, tendons and muscles than tiger bone. Thus giving up the use of tiger bone would not have much effect on Chinese herbal treatments. Since the use of tiger bones was banned, mainland China has still been producing Quince and Tiger Bone Wine, but with a notice on the bottle reading "Does not contain tiger bone." But because of the way in which some people in Taiwan have exaggerated the curative powers of tiger products, we have had sanctions slapped on us by the United States, however unfairly.

In Taiwan's temples, the tiger is the commonest animal spirit by far. When the City God makes his inspection tour, the tiger spirit Huyeh plays a part in the procession. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

However, whether they betray a love-hate attitude or are contradictory and confused, the many different ways in which we refer to the tiger in fact all go to show how close a relationship the Chinese have with this animal.

In the section in Ku Chin Tu Shu Chi Cheng ("Completed Collection of Graphs and Writings of Ancient and Modern Times") which records Chinese people's relationships with animals, the poems and stories about tigers far outnumber those about any other creature.

"All the different emotions we feel towards the tiger have sprung from people's real-life contacts with tigers." Chien Sung-tsun notes that the rhinoceros, for example--another large animal which was once found in China--was hunted in the turbulent Warring States period for its skin, which was used for armor. With this pressure, combined with changing climate patterns, by the Han dynasty it had already disappeared from China. Today, apart from the medicinal use of rhinoceros horn powder and a few rhino horn artifacts which have been passed down from ancient times, any trace of the rhinoceros has long disappeared from Chinese people's lives.

It's just that today it is not only on the spiritual plane that the once revered tiger is "down from the mountain and at the mercy of dogs," wide open to fictionalization. In real life too, following in the rhino's footsteps, the tiger is on the verge of disappearing from China, its original home. From the South China tiger in the south to the Bengal tiger on the borders of China and India, and the Siberian tiger, throughout China there are less than 100 tigers in all. The animals are on the very brink of oblivion.

If the rhinoceros is anything to go by, if the tiger disappears, the Chinese cultural tradition of venerating the tiger will also sooner or later be broken. Even though the tiger beliefs which run deep in folk culture will not disappear easily, without the tiger, won't tiger culture, which will remain in form only, be lacking something?

[Picture Caption]

From a totem of old tribal society to a folk symbol to bring good fortune and drive out evil, the tiger is not only the fiercest animal in China's jungles--its images is found everywhere in Chinese people's lives. (picture at left courtesy of Weng Ching-huo)

As farmland expanded and hunting methods advanced, later generations viewed the tiger differently from earlier ones. On Shang dynasty bronzeware, the tiger always had an air of mystique: pictured at left is a Shang utensil decorated with the image of a tiger eating a man. In the Han dynasty fresco of a hunting party, at right, the tiger has become the quarry in the chase. (courtesy of National Palace Museum)

When Lungshan Temple in Wanhua celebrated its 250th birthday, this tiger float added to the excitement. (Sinorama file photo)

How will my luck be this year? Watch out for the white tiger gate--it's as dangerous as the gates of hell. (photo by Yang Wen-ching)

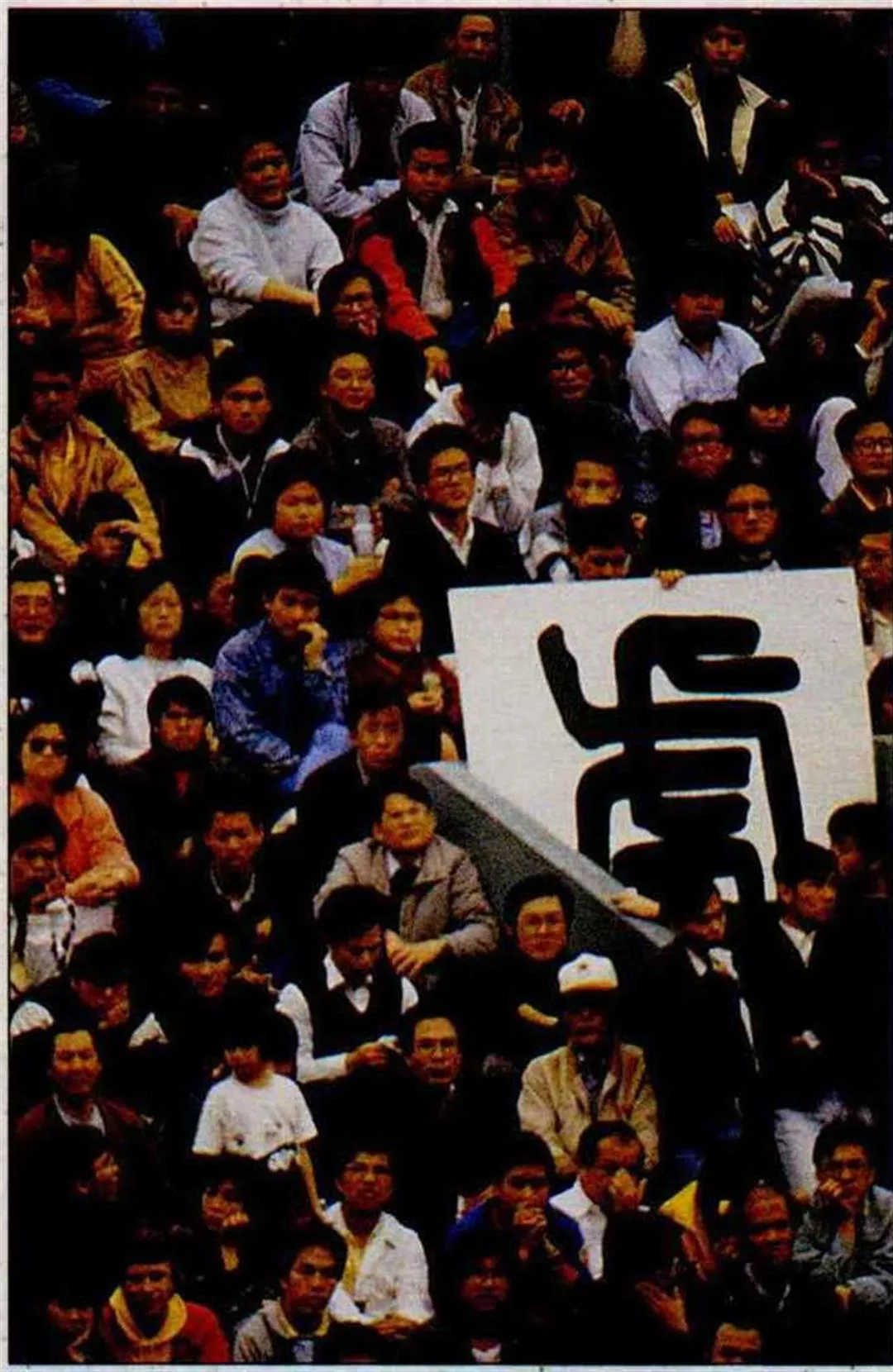

Is the tiger away from the mountains at the mercy of humans? Except in zoos, tigers today are seen almost only in pictures. Here we see a large "tiger" character identifying supporters of the San Shang Tigers professional baseball team at a game. (photo by Lily Huang)

In Taiwan's temples, the tiger is the commonest animal spirit by far. When the City God makes his inspection tour, the tiger spirit Huyeh plays a part in the procession. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Painter Wu Hau's Festive Tiger is a lively, lucky, lovable folk art tiger. (courtesy of Wu Hau)

Buddhism brought the image of the lion into China, robbing the tiger of much of its glamour. But the tiger is still a powerful symbol to drive out evil. Pictured here is a "tiger" character stele on Tsaoling old military road. (photo by Chung Yung-ho)

Painter Wu Hau's Festive Tiger is a lively, lucky, lovable folk art tiger. (courtesy of Wu Hau)

Buddhism brought the image of the lion into China, robbing the tiger of much of its glamour. But the tiger is still a powerful symbol to drive out evil. Pictured here is a "tiger" character stele on Tsaoling old military road. (photo by Chung Yung-ho)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)