When the British speak of the "Great Tea Races" of the mid-19th century, they stress that they were even more splendid and exciting than the world-famous Grand National steeplechase. How can competitions with tea be compared to competitions with horses? In fact these English-style tea races had nothing to do with aroma,flavor or color; speed and risk were what they had in common with horse races. And the thoroughbreds which people craned their necks to see and laid crazy bets on were ships: the fast "clippers"--specially developed to carry China tea--which plied between the China Sea and the English Channel.

"When you climb aboard the Cutty Sark you take a step back in time to the most exciting days of merchant shipping, the Great Ship Race from China, when folk around the world waited with bated breath to see which vessel would be first to bring the new season's tea crop back to our shores," the voice of the straightforward and engaging Captain S.T. Waite, Master of the Cutty Sark, had boomed sonorously over the telephone. But when we met him he was not wearing a crisp white uniform as we had imagined, but a business suit, with a tie bearing the image of a sailing ship: the logo of the Maritime Trust. And his job was clearly not to steer the ship out to sea to bring back a cargo of tea, but to keep alive in people's memories the legend of the fast clipper ships.

The legend of the clippers lies in their brief splendor and their sad passing as they were overtaken by history. They blossomed in the time between the decline of the old-style sailing ships of the East India Company's oriental trades and the rise of steamships. After only two decades they disappeared from the busy stage of maritime trade. Today they can only ride out the years in the harbor of time.

The gorgeous young woman has a fatal attraction which draws the KYV errand boy into her trap. (still from Treasure Island courtesy of City Films Ltd.)

The Cutty Sark, which lies at Greenwich in England, is now the only surviving 19th-century tea clipper. Her masts tower into the blue sky, crisscrossed with her rigging, and though her sails remain stowed away we can still imagine something of the grace with which she once sailed the seas. Climbing down into her hold, we are confronted by wooden chests stacked layer upon layer, marked with scrawled Chinese characters identifying the contents as black tea, green tea or imperial tea.

When the clippers raced with their precious cargoes it was the age of sail and the age of tea. In the 17th century, when tea--that "excellent China Drink"--was first brought to Britain, it immediately became the favorite of royalty and nobles. Although heavily taxed in the 18th century, tea quickly won ever greater popularity (see last month's cover story "Who Put the Tea in Britain?"), and particularly after the British Parliament passed a law greatly reducing the tea tax at the end of the 19th century, it became the national drink and demand for it rocketed.

But if we look at the way tea was shipped and sold, I'm afraid that the imported China tea which the Queen and noble ladies drank in those early years would today have to be called "old tea." The sea journey from China to Britain was long and hazardous and passed through pirate-infested waters. The sea voyage took well over a year, and with the perils of typhoons and hidden reefs, cargoes of tea were often damaged and seldom arrived fresh.

One 18th-century ship's log records how an East India Company merchantman returning from Canton with a cargo of 1000 cases of black tea ran into a "Gale of Wind" only half way home and took in several feet of water. The crew discovered that "a box of Sugar Candy ... had been washed out ... and ... several chests of Tea had been wet."

Furthermore, to ensure a steady supply, once the tea arrived in Britain it was often stored for a year or more as a hedge against poor harvests and delayed shipments. Thus the tea sold at such high prices in London was at least two years old.

"In the 18th century the China trade was the monopoly of the East India Company. There was no competition at all and they had no motivation to improve." Captain Waite explains that the concept of "new season tea" did not emerge until after advances in shipping.

Chen Kuo-fu has always got around by bicycle. He believes that in urban Taipei, cycling is safer than riding a motorbike.

Before the age of air travel, the wings on which mankind's dreams took flight were the oceangoing sailing ships. They intimately linked human ingenuity and the forces of nature. The great sailing ships rode the wind across the far oceans and brought back countless tales of oriental wonders. But sadly, for the Chinese, the direct and indirect reasons behind the advances in shipping from the late 18th century onwards are tokens of a bitter history.

The story goes like this: In 1784 when the British tea tax was cut, demand for tea increased sharply. At that time the only Chinese port open to foreign trade was Canton. Foreign merchants had long been dissatisfied with this situation, and their activities were further hampered by all kinds of restrictions placed on them by the Chinese "Hongs" through which they had to trade. Britain repeatedly sent diplomatic missions carrying rich gifts to seek audiences with the Chinese emperor Qianlong, but they only brought back equally large numbers of gifts, and made no progress on the subject of trade.

The "Celestial Empire" was endowed with material wealth and prosperous subjects, and was selfsufficient. Apart from the silver it earned by selling tea it was not interested in anything the West had to offer. But to balance the enormous deficit from the tea trade, British ships carried opium from Britain's Indian colonies, and this saved the situation by earning the British merchants massive quantities of silver. In 1796 China prohibited the import of opium, and in the same year the East India Company also officially banned its sale. But this turn of events prompted the development of a new type of ship, to serve the needs of smugglers. "The need for fast small ships to escape detection by war junks or pirates, and capable of running into smaller ports along the coast to prohibited areas of Northern China, brought about a new breed of ships," writes George Campbell in his China Tea Clippers.

Whether in the case of divorce or the death of a spouse, harm to the child can only be minimized if the adult can escape from pain and achieve emotional equilibrium.

Necessity is the mother of invention, and the need to reap huge profits is clearly an even greater stimulus to inventiveness. When the East India Company's monopoly was abolished in 1834, merchants scrambled to do what they had long wished for: to get into the ever-lucrative China trade. When in 1839 the imperial commissioner Lin Zexu embarked on a campaign to eradicate opium and wrote an eloquent letter to Queen Victoria, the British response was one which pains the heart of every Chinese to this day: the Opium War of 1840, described by English-language history books as "the first Anglo-Chinese war, which arose out of a series of small incidents." Lin Zexu was removed from office in disgrace, but "won respect" in Britain, where his figure stands in London's Madame Tussaud's waxworks. Surely he would have been aghast at being thus placed among the very people who forced opium on his compatriots!

The outcome of the Opium War was the unequal Treaty of Nanking which we are all familiar with: it ceded Hong Kong to Britain, and opened the five ports of Guangzhou (Canton), Xiamen (Amoy), Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai to unrestricted foreign trade.

As these five ports were all close to the teagrowing areas of southern China, the supply of tea became abundant and uninterrupted, and after the Treaty of Nanking the huge stocks of tea held in London's warehouses expanded so much as to become a worrisome burden.

The great increase in the volume of trade boosted demand for ships and for speed, and at a time when tea drinking of itself was no longer a mark of high social status, "new season tea" became the latest symbol of good taste for the connoisseur.

As well as the constantly growing China tea trade, the clippers were used on routes from the American East Coast round Cape Horn to San Francisco and across to Japan and China, and the Gold Rush of 1848-9 also created an urgent need for fast passages to California. Previously the size of the payload had been the prime consideration in ship design, but now light weight and speed became the priorities.

In 1849 Britain's Navigation Acts were repealed, allowing ships of other nations to carry goods to and from British ports, and this brought even greater competition into the shipping world. The United States took the early lead in this intense rivalry. On 3 December 1850 the first clipper, the Oriental, appeared victoriously at London having sailed from China with a cargo of China tea in the record time of 97 days. This feat aroused general astonishment, especially among British shipwrights.

"Although American clippers took the lead initially, the British later gained the upper hand." Captain Waite stresses that because British seafaring already had a history of many centuries, by the mid-19th century the country faced a severe shortage of timber for shipbuilding. Necessity is the mother of invention, and when the Industrial Revolution brought iron and steel, Britain developed composite clippers built of wood and iron. Their iron framework was lighter and stronger than a wooden frame, and greatly reduced the weight and volume of timber required. America had vast quantities of timber available, but the US imposed heavy taxes on iron imported from Europe, making it difficult for US shipyards to follow suit. This is why the main performers in the great tea races were later mainly British-built vessels.

But just what set of circumstances enabled the clipper ships to reduce sailing times so miraculously and develop the great tea races?

Children are our burden, and also our hope. Single parent families often put their children under severe pressure from excessive expectations.

David MacGregor, an authority on clippers, has devoted many years to researching the tea ships. He has written at great length illustrating and comparing the design of the clippers' hulls and prows, to explain how they were designed for the perils and rigors of the China Sea. But he is at pains to emphasize that it was not so much the ships which had changed, as the men and their incentives.

In the era of the East India Company's monopoly over the oriental trades, there was no competition between merchant ships. It is said that in those days when ships were at sea, at nightfall or whenever a squall threatened, the crews would reduce the sails, and ships would put into port on the slightest pretext. But the age of the clipper ships was a period of unprecedented romance for Britain, when the whole country was gripped by indescribable enthusiasm.

"Of all the decades in our history, a wise man would choose the 1850s to be young in," said the British historian G.M. Young.

It was an extraordinary time. The steam engine and the railways were carrying the British headlong towards a supposed paradise of scientific invention and rapid industrial development. Wise men would soon find the answers to all mysteries, and people were working indefatigably to make all kinds of impossible dreams come true. The impressive machines and engines on display in the Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition of 1851 were worshipped and admired like masterpieces on an altar, and we should not be surprised if the British of the time were in fact more interested in the tea ships themselves than in the new season tea which they carried.

And since consumers cared so much which ship their tea had arrived on, every year the clippers of different owners raced madly, riding the monsoon winds. Those at sea wagered their lives, while those on land wagered their money. After all, it was an age when man believed he could subdue nature, and when competition was supreme.

Foreign ships mass on the Min River at dawnAt Fuzhou from April to June, the tea growers were busy bringing in the spring tea harvest, and Pagoda Anchorage in the Min River was crowded with foreign ships waiting to load. The Min River in spring held many wonders in the eyes of mariners from distant lands. An apprentice on a 19th-century clipper recorded in his travelogue the scene at this main port for the export sale of new tea.

He describes how in the evening the captain sighted a lighthouse near the Min estuary. As night fell they dropped anchor. At daybreak the next morning they loosed their sails, weighed anchor and continued towards the river mouth, soon signalling a pilot boat. The custom here was that ships would first be guided by foreign pilots on the open sea, with Chinese pilots only taking over on the river.

Along the Min River, green mountains towered high on both sides as far as the eye could see. Sometimes there would be paddy fields all around, the terraced fields snaking their way up the slopes. Then in an instant the scene would change to rocky mountains with a few straggling firs, the rocks now black, now purple according to the light. Of course, the fantastic roofs of farmhouses in distant villages also caught his gaze.

They sailed upriver for a whole day before again dropping anchor for the night, and only on the next day did they actually reach their destination: Pagoda Anchorage, where foreign ships waited to load tea. Here the river suddenly widened; on one bank one could see European houses and an English chapel, and on the other the Chinese custom-house, also of European architecture. High on a ridge stood an ancient pagoda. The pagoda he described was the internationally known mariners' landmark Luoxing Pagoda in what is now the Mawei district of Fuzhou City.

In those days London tea merchants usually entrusted the task of buying tea and choosing ships to British trading companies established in China, although some companies did set up offices with their own personnel to take care of these matters. In turn, the trading companies hired savvy local compradors to negotiate with their Chinese suppliers. Each year when the tea season came around, as the harvest was gradually gathered in, the brokers would send out their "tea men" to choose the tea and negotiate prices. This was a lengthy process with much tough bargaining. Sometimes it took a whole week before a deal was struck, and only then would a ship be selected to carry the tea.

Chinese stevedores were expert tea stowersIt is said that in the 1860s, when the clipper tea races were at their height, representatives sent from London would often be so eager to get their goods on board ship that they did not have the patience to negotiate the keenest price, nor were they willing to wait until the best black teas came on the market in late May. They preferred to pay high prices to have tea hurriedly packed, loaded onto the clippers and rushed back to England. The result of this was that the so-called new season tea brought by fast ships was in fact second-rate leaf with old tea mixed in.

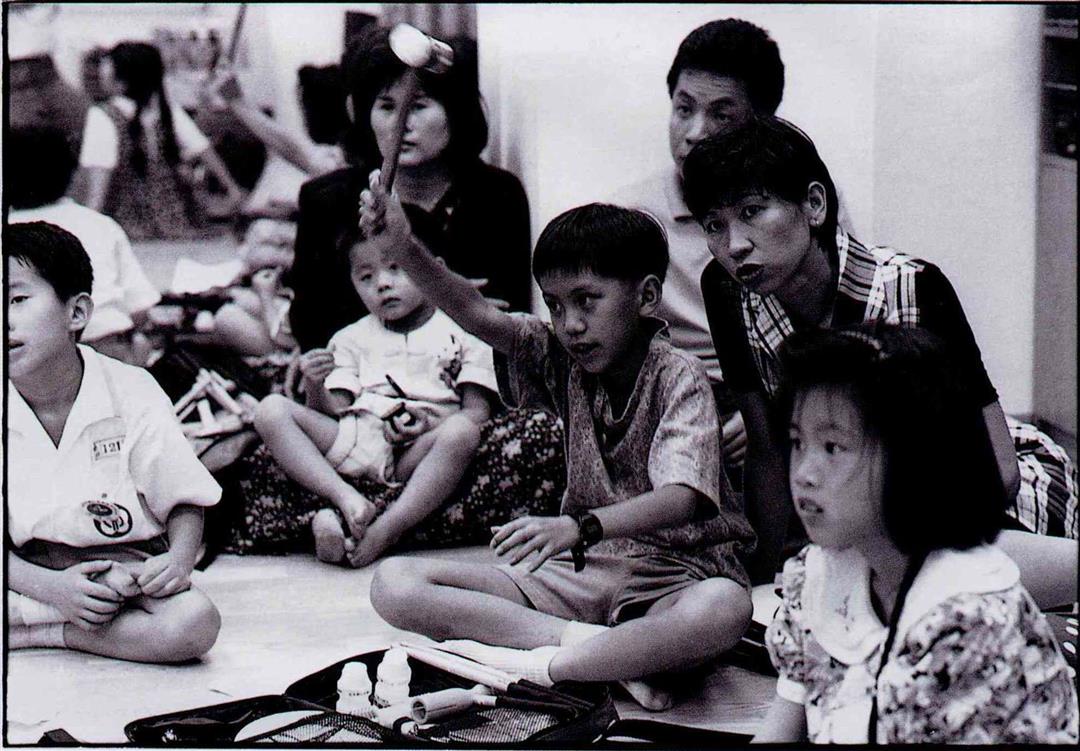

After the tea was bought and a vessel chosen, the tea had to be loaded into the ship's hold, and this task was performed entirely by Chinese stevedores. The clippers were designed to carry tea, and they had some 100 tons of iron kentledge (ballast) built between the floors of their holds. They would also use another 150 to 250 tons of shingle, of which three-quarters was spread in the bottom of the holds and the other quarter was stuffed into the spaces along both sides during loading. When the sampans brought chest after chest of tea wrapped in bamboo strips and oiled paper and lined with lead, the stevedores expertly packed them tightly into the hold, starting with the cheapest teas at the bottom. As they built up layer upon layer, they used different sized chests and stone dunnage to pack the tea chests together seamlessly, then used wooden mallets to tap the surface of each layer down as flush as a ship's deck.

A clipper could generally load about one million pounds of tea, and if it could catch favorable winds and be the first ship to unload in London or Liverpool,the cargo would command a premium of around 10 shillings per ton, and the master would also earn a handsome bonus and gain lifelong honor.

A natural love of riskNo-one can say just when the famous tea races really started; they were not organized by anybody, and there was certainly no starting gun and no rules to be adhered to. The tradition of the clippers racing home with tea started from purely commercial motives, but it became the natural expression of human nature and the spirit of the times.

The China Sea was notoriously hazardous and poorly charted, and seafarers showed extraordinary perseverance, courage, knowledge and skill as they pitted themselves against each other. Back in the days of the East India Company's monopoly there had been stories of merchantmen furling their sails and stopping every night; but the stories of the clipper age told of captains eager for swift progress putting padlocks on the sheets before going to bed, to prevent the mate on the night watch reducing the sail area without permission. It is said that the clipper captains were especially young, because older and wiser captains with their richer experience would naturally not be as willing to take risks.

The clippers which set out from the same Chinese ports might spend the next 100 days charting their own ways across the oceans without seeing each other again until they excitedly reached the English Channel, where in the light of dawn they might suddenly find themselves in the company of their rivals. Then the tea race would reach its climax. When a semaphore signal station caught sight of the first ship, within a few seconds the news would be transmitted from hilltop to hilltop to the shipowners in London. From that moment the owners would keep their eyes glued to the weather vane, praying that their own ships would be first to dock.

The decisive last dashThe final test came in the 60-mile dash up the Thames to London.

At this point steam-powered tugboats would come out looking for business, demanding different rates according to their power and speed. We can imagine how galling it must have been for a hardheaded master who had braved the winds and waves to come so far, to furl his sails for the last leg of the voyage and submit to being led into dock by an ugly little tug. So when tugs on the river threatened to dirty the clippers' white sails with their black smoke, one might often see the clippers' irate crews threaten to pour a bucket of water down the tugs' little funnels.

Sometimes the clipper captains paid a price for maintaining this last bit of bravado. One year a clipper running before the wind was leading the way up the river, making such good time that the master haughtily refused the help of the best tug, which disappeared astern to take his rival in tow. But then the wind died away and to his chagrin he saw the race to the final docking slip from his grasp.

Captain Waite says that the most famous tea race in history was in 1866. Sixteen clippers left Fuzhou in China in the space of 24 hours, and after a voyage of 12,000 nautical miles and 99 days at sea, several arrived in the English Channel within sight of each other. Finally the Taeping and the Ariel unloaded their first cases of tea within just twenty minutes of each other!

The Cutty Sark has also been cheered into harbor, but she was never first home in a tea race. In 1872 she lost her main rudder in a storm while bound for London. The owner's brother demanded that the ship put into South Africa for repairs, but the master insisted on continuing the voyage, and the two almost came to blows over the argument. In the end two stowaways on the ship--fortunately one was a carpenter and the other a blacksmith--worked together to make a temporary rudder, and the Cutty Sark reached London safely 122 days after leaving Shanghai. The story became a favorite yarn.

Born behind the timesThe very names of the clippers conveyed their romance. The Ariel, which missed winning the 1866 race by 20 minutes, was named after a sprite in Shakespeare's play The Tempest, while the Cutty Sark's name came from an ancient Scottish legend recounted in Robert Burns' poem Tam O'Shanter. Tam, a farmer, was riding home drunk on his grey mare Maggie when he glimpsed what seemed to be a fire in Kirk Alloway. A group of witches and warlords was dancing with the Devil to the skirl of bagpipes. The astonished Tam saw that among the old hags there was one young and beautiful witch, Nannie, who was dancing wildly dressed only in a "cutty sark"--a short shirt of Paisley linen. Tam was captivated and, forgetting himself, gave a shout of encouragement. In an instant everything went dark, and the witches broke off their dance and began to pursue him. He leapt onto his mare and galloped for the bridge over the Doon, for witches cannot cross running water. In less time than it takes to recount, Maggie reached the bridge, and she sped across it just as Nannie seized her by the tail, which came off in her hand.

This is why the Cutty Sark's figurehead is in the form of a woman rushing headlong; in her outstretched left hand she grasps a piece of ship's rope placed there by the sailors as the "mare's tail."

Perhaps the figure of Nannie pursuing the object of her desires represented the hopes which the Cutty Sark's owner placed in the ship. But the way Nannie seas her prize slip away across the bridge before her very eyes, leaving her holding only a broken dream, seems to presage the Cutty Sark's fate.

"In fact the Cutty Sark was out of date when she was born." Captain Waite explains that the heyday of the tea clippers was from about 1850 to 1875. The Cutty Sark was built in 1869, the year the Suez Canal opened. The canal's opening was an important event in maritime history, but it was instrumental in the decline of the tea clippers.

Replaced by steamSteamships had existed before that time, but they could only operate over short distances. In 1843 a steamship crossed the Atlantic for the first time, but the engines of that period were not reliable and the ships still carried sails and oars for emergency use. Furthermore their boilers were heavy and they needed to carry large quantities of coal which occupied much space and added much weight. Also, steamships needed to put in frequently to refuel, so up until the 1870s the long-distance, highly competitive tea trade was still mainly the preserve of sailing ships.

In 1866 the installation of a new type of more economical engine in the Liverpool-built steamship Agamemnon changed history. She sailed from Fuzhou to London with a cargo of tea in only 86 days! We can imagine how heart-sickening it must have been for the crews of the elite clippers of the time, as they waited to load tea at Pagoda Anchorage, to see the Agamemnon steam arrogantly past them, her great funnel belching a black smoke which symbolized progress and power.

Naturally people still had a lingering affection for the grace and romance of the tea clippers with their billowing sails, and some insisted that the steamships reeked too strongly of coal, making them unsuitable for transporting tea.

But sadly no amount of nostalgia could arrest the breakneck speed of change in that era. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869, ships bound for the Orient no longer had to round the Cape of Good Hope. The distance between East and West was vastly reduced, and there were many refueling stations along the new route. By the late 1870s, the tea clippers had been almost completely replaced by steamships.

A lone witnessThe fate of the Cutty Sark was no different from that of the other clippers. After withdrawing from the tea trade she variously engaged in the Australian wool trade and emigrant transport, and took whatever work she could find until her owner could no longer operate her economically, and sold her to a Portuguese buyer.

But luckily in the 1920s she happened to meet an old admirer. Although sailing under a different name, she was recognized by an old captain who had known her in her heyday, and he bought her and brought her back to England to serve as a training ship. After World War II she was again neglected and might nearly have been scuttled, but London County Council paid for initial repairs, and a society was set up to undertake her full restoration, after which she was put on public display at Greenwich as the only remaining witness to the brief but glorious history of the tea clippers.

[Picture Caption]

p.114

Captain Waite's job is evidently not to sail the seas and carry back tea, but to keep the legend of the clipper ships alive in people's memories.

p.115

When the tea ships reached Britain, the dock workers, who included Chinese, worked busily to unload them. As they worked, the tea merchants were already breaking open the first cases to sample the tea.(courtesy of the Bramah Tea and Coffee Museum, London)

p.116

Famous clipper ships have been the subject of many paintings. Depicted here is the final dash of the Taeping and the Ariel in the most famous tea race, that of 1866. (courtesy of Cutty Sark)

p.117

(Map:Lee Su-ling)

In 1748, the British Captain Anson, after capturing a Spanish ship, sailed his prize towards Macao to ask to take on water and provisions; but his intentions were misunderstood. From the pictures we can compare the different lines of the old-style 18th-century sailing ships and the clippers.

p.118

A calendar card given away in the late 19th century by a firm of English tea merchants. It shows the whole cycle of tea being grown in a tea garden, leaving Shanghai, arriving in London as "new season tea," and being put away in the warehouse. (courtesy of the Bramah Tea and Coffee Museum, London)

p.121

These samples of China tea in the Cutty Sark are tied with beautiful silken threads, with different colors representing different kinds of tea.

p.121

Replica tea chests on the Cutty Sark. They hold black tea and imperial tea, a kind of green tea. In real life her hold would have been crammed full of such chests.

p.121

Tea from a Swedish East Indiaman which foundered in 1745. When it was salvaged in 1984, it still retained much of its flavor, showing how well it was packed all those years ago.

p.122

The Cutty Sark's figurehead Nannie was originally carved from softwood, and today to preserve it safely it is put on display inside the ship's hold, while a replica does duty outside under the bowsprit.

p.123

The Cutty Sark's hold houses an exhibition in words and pictures on the history of the tea trade and the clipper ships. She attracts visitors from all over the world.

p.123

Whether the Cutty Sark can continue to ride out the years in the harbor of time still depends on everyone digging into their pockets to help.

p.124

London's famous Tower Bridge was built in 1894. The spot was previously the finishing point of the great annual tea races.

p.125

Both banks of the Thames near Tower Bridge used to be lined with tea warehouses. Shown here is Butler's Wharf, where the record for the number of chests of tea unloaded in one day was 5000. There are plans to buy Butler's Wharf to house a tea museum.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)