The Voice of Working People:Kaohsiung Museum of Labor

Kuo Li-chuan / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

April 2010

Be quick, arise / And of your own free will / Awaken the road to work / Press ahead with the crowds / To arrive before eight

Hurry to your post, everyone / Check your watch repeatedly / Quicken your pace / Please don't hit the horn so hard, friend! / Everyone is equally rushed at this hour

Beads of sweat flowing down your face / Dry in the wind to leave salt / How brilliantly it catches the light! / Remember: Don't hold feelings of inferiority / Brandish your industrious pair of hands

We too can / Turn the tiny into the great / Turn the fleeting into the eternal / Spend life ever rising, / Ascending the ladder of growth-Li Changxian, "Ode to Labor"

From shipbreaking and petrochemicals to steel production, the harbor city of Kaohsiung has long been the center of heavy industry in Taiwan. In 1966 it also became the site of the world's first export processing zone, helping to forge the Taiwan economic miracle and also providing an economic model that would be copied around the world. Behind this glorious history are countless workers at all levels who have devoted their sweat and their lives to the city's success.

In order to honor those unsung heroes and to preserve images and historical records of labor culture, the city of Kaohsiung has established the Kaohsiung Museum of Labor, the first museum of its kind in Taiwan. Its formal grand opening will occur on May 1, International Workers' Day. But ever since it "pre-opened" on December 26, it has drawn enthusiastic crowds, with an average of 5000 people per day on weekends. The number of visitors even went as high as 40,000 per day during the Chinese New Year's holiday in February. The museum, barely over 10,000 square feet in area, was jam packed.

Sausage, cigarettes, betel nuts and all manner of energy drinks-there's not a lot of subtlety to the typical diet of low-level workers in Taiwan. It's quite the opposite of the gourmet and vegetarian fare that can be found in Taiwan's cities today.

As an industrial city and as home to many state-run enterprises, Kaohsiung has laid a strong foundation for Taiwan's labor movement as a whole. Labor has always been very innovative there, and in 1999 a group of labor activists established the "Labor Autonomy Committee." Reflecting on how the lives and culture of low-level workers quickly return to being ignored after celebrating International Workers' Day every May 1, and how the skills used in many traditional industries were disappearing with the passage of time, committee members, including then-chairman Chung Kung-chao (now Kaohsiung City director of labor affairs), former labor affairs director Wu Qingbin, Chunghwa Telecom Workers' Union secretary-general Simon Chang, and head of the Kaohsiung Port Stevedore Union Shi Yonglin, proposed a labor museum. They quickly got approval from the city and began planning.

Now, six years later, having collected abundant visual images and oral histories, the museum is ready to open. Several sites were considered, but at the end of 2008 a site in Taiwan Sugar Corporation's old C4 Warehouse District within the Pier-2 Art Center was selected. The area was the first developed at Kaohsiung Harbor, and the nearby railway also served as an important mover of goods and raw materials. In era after era, developments in this neighborhood have played key roles in Kaohsiung's economic transformations.

Since the masses of workers are its focus, an emphasis was put on breaking down the barriers between the visitors and the holdings. The 10,000-square-foot museum was designed as an undivided space, without walls, cordons, or glass cabinets. Unlike in most museums, visitors here can touch and photograph every item on display, and they are encouraged to participate in various activities. To give visitors a sense of the warm cordiality of the harbor city, the museum specially built a long skylight, which floods the space with natural light. It both reduces lighting costs and also provides a warm, well-lit feeling that suggests greater intimacy with people's lives.

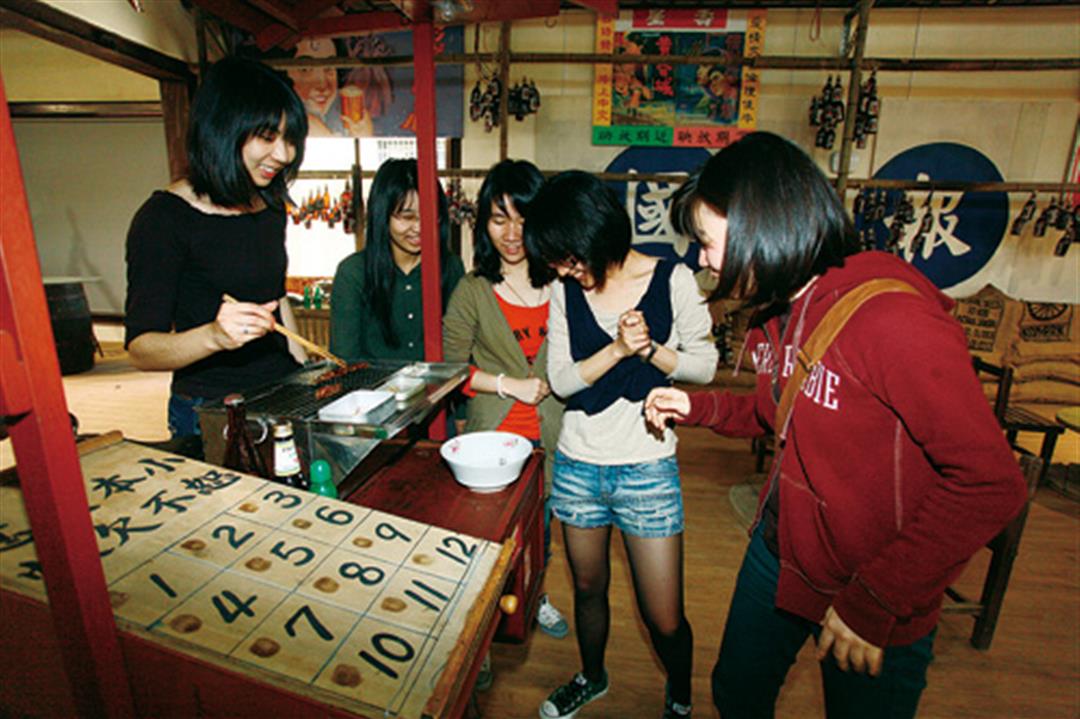

In the version of Monopoly that can be found to the left of the museum entrance, players immediately start making decisions for a worker-choices that can have a big impact on the way their lives turn out.

On the outside walls of the museum, near its front door, visitors see depictions of various workers in black acrylic paint by Wang Qingxin, a veteran painter of billboard film advertisements. To the left of the entrance, a Monopoly board has been painted on the ground, where you also find two huge dice.

In the board game of Monopoly, the winning player wipes out all the other players to become a real-estate magnate, monopolizing all of the board's property. In fact, the museum looks critically upon that "winner-take-all" mentality of modern capitalism as practiced on Wall Street.

In the museum's version of Monopoly, aspects of workers' lives are interwoven with the development of Kaohsiung. There are four major thematic areas: "export processing zones," "workers' food and drink," "workers' literature," and "the labor movement." These are then further divided into individual spaces with varying content.

At "Go," a player must make a decision that confronted many young people in the 1960s: Should you stay on the family farm or become a worker in the cities? "For men, the worst thing is to go into the wrong profession," the saying goes, "and for women, to marry the wrong husband." The future is always a source of great apprehension.

"Many workers would move to towns and find jobs in factories and only then slowly learn how to become a worker," explains Chen Xueni, director of the Kaohsiung City Labor Education and Life Center.

Apart from some easygoing squares, such as "Eat midnight snacks at night market," players can also land on squares with more serious subjects: "Selected as a representative in negotiations with management," "Fraudulent bankruptcy: lose job and pension," or "Co-worker dies on job." These circumstances may evoke sad recollections for many workers. To cheer players up and to demonstrate the shared values of Taiwan workers, "happiness" and "courage" are scored as well as "money" and "fame."

The Kaohsiung Museum of Labor is located in an old Taiwan Sugar warehouse. Its formal opening is set for May 1, International Workers' Day. The museum, which celebrates more than 60 years of labor in Taiwan, is a treasure to be enjoyed by all of the people on this island.

In the 1950s the United States, Japan and other nations began to move their labor-intensive industries abroad, and Taiwan moved toward economic liberalization and an export orientation so as to attract foreign investment. In 1960 the Legislative Yuan passed the Investment Incentive Act, and at the end of 1966 the ROC established the world's first export processing zone in Kaohsiung. Export industries such as textiles and electronics were labor intensive, and women were favored for their attention to detail. It's estimated that Taiwan's three export processing zones employed more than 100,000 women at their peak.

In 1972 the Kaohsiung poet Chen Kunlun wrote "Working Girl." It faithfully records the situation of female workers during that period:

Ah-hua collects her pay / She counts the bills from first to last / And then from last to first / One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine / One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine

Three of them will pay her rent / Three she'll send to Mama / The final three she'll spend on Max Factor, / Shoes and a miniskirt

These young women who had left their hometowns to find work used their meager wages to pay their rent, help their families, and keep themselves fashionable. That might mean going without breakfast, so that they'd arrive at the factory in a miniskirt but on an empty stomach. Perhaps they imagined that one day they would transform themselves, like the heroine of a Qiong Yao novel, by meeting a knight on a white horse who was both a cultured gentleman and fabulously wealthy.

Under traditional Chinese conceptions that value boys over girls, parents put top priority on educating their sons. The daughters, meanwhile, typically entered the workforce after elementary school or junior high. Along with finding economic independence, these girls and young women still wanted to pursue their studies. Intent on advancing their educations even without their family's help, many would go to night schools or subsidiary schools (designed for older students) after they got off work. Chen recalls that Kaohsiung's subsidiary schools back then were packed full. That striving for educational attainment represents another kind of Taiwan miracle.

In Taiwan women's participation in the workforce has always been low (it was 39.13% in 1978 and still only 49.62% in 2009-well below the US rate of 60%). But even if women stay out of the labor force for various family reasons-whether to care for their children or for their husband's parents-they have always worked hard. And often their paid work isn't included in official statistics: A small number have opened food stalls and become their own bosses; many more have earned a little extra cash by doing piecework at home.

In the mid-1970s, under former Taiwan governor Hsieh Tung-min's "home as a factory" policy, Taiwan formally entered a period of economically mobilizing its entire population. From the handmade Christmas lights and stuffed toys early on, to the piecework for apparel makers in the current era, women's skilled hands have long helped to put the label "Made in Taiwan" in every Western home.

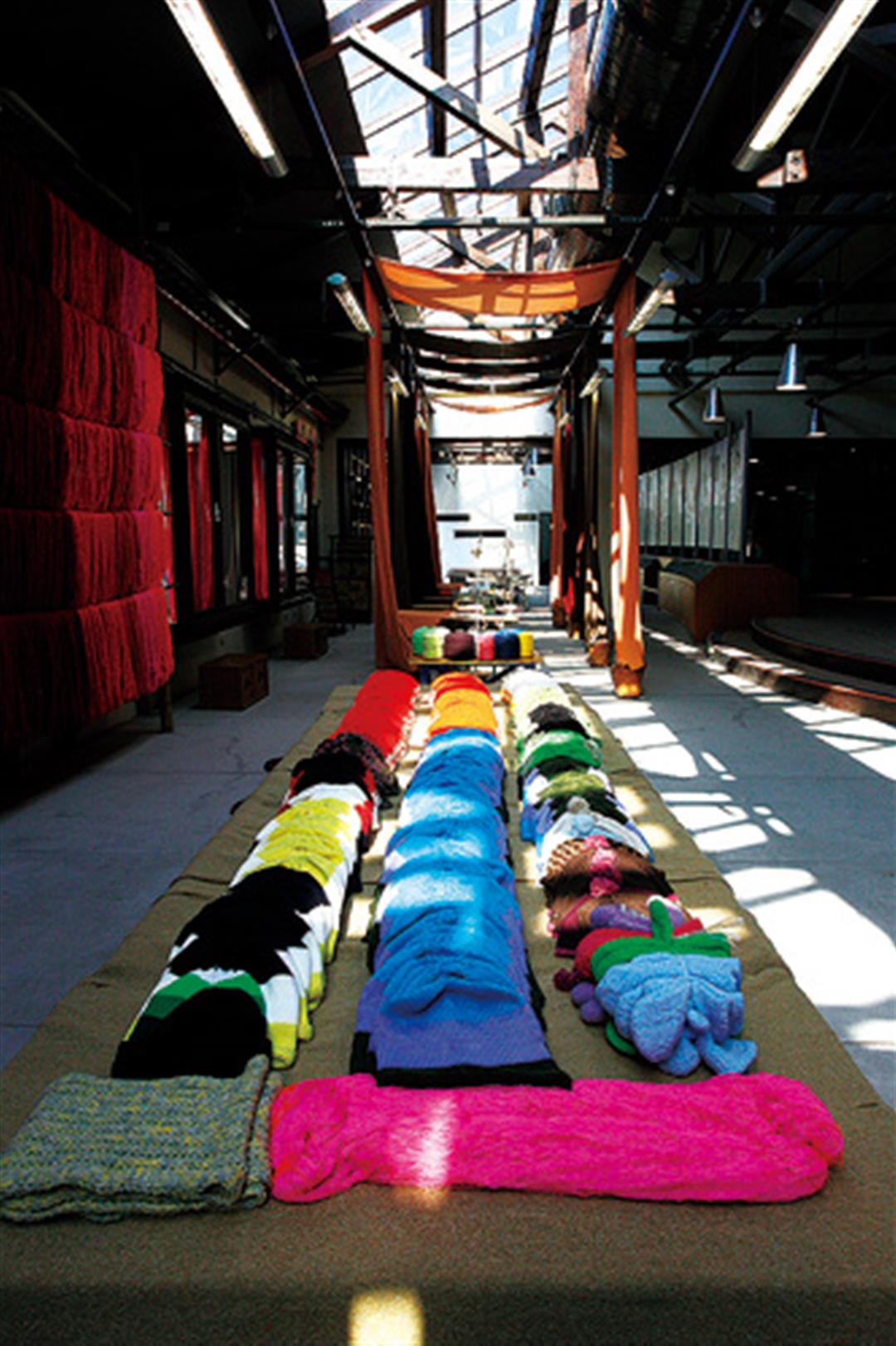

Taiwan's minimum monthly wage is now NT$17,280. Meanwhile, the going rate for affixing pompoms is just NT$2 per ski cap, so you'd have to cut the wool on 8,640 pompoms just to make the minimum monthly wage. Piled up, the yarn required for that many pompoms would cover a whole wall!

The various textile products spread out on a low platform bear witnessto the economic miracle rendered by individual families under government policies "to turn homes into factories" and "economically mobilize the entire population." In some tows many households still do piecework at home.

Under the museum's bright skylights, one finds literary works by famous labor-movement writers, such as Mo Shangchen, Li Yufang, Li Changxian and others. Among them, Yang Qingchu's Factory Girls (1970) could be described as the book that truly awakened a labor consciousness.

When women factory workers organized unions the following year, many were fired and others were berated by their employers, who told them to "come to their senses." After a Kaohsiung ferry capsized in 1973, killing 25 young women factory workers (to whom a memorial was later erected), the safety and rights of workers began gradually to become a political issue. In 1984 the Legislative Yuan passed the Labor Standards Act, giving more than 3 million workers in Taiwan some basic protections.

But in that same decade many factories moved overseas, and many companies were fraudulently going bankrupt to evade paying required pensions. Older workers were most affected, and labor strife was rising.

In 1988 the Shinkong Spinning plant in Shilin closed, angering more than 400 women who had devoted their working lives to the plant. In response they occupied the plant, preparing food as if they were on a campout. The 76-day protest extended into the next year. It was the first of many demonstrations sparked by plant closures.

During the Museum of Labor's "pre-opening" period, curators considered that era of labor strife and designed an area of the museum devoted to it with the theme: "Workers' Spirit." A large sign was emblazoned with the words: "Oppose Unemployment, Protect Our Livelihoods-Workers of the Nation Unite!" Various head sashes worn at demonstrations during that era, including those emblazoned with slogans such as "Give me back my rights," "Unemployment is an urban cancer," and "Long live labor," were attached to the back of the sign.

Although the wave of factory closings has already passed and the Labor Standards Act has been revised so that pension contributions are placed into worker's individual pension accounts, the trend toward using hourly paid and agency workers makes unfair compensation still a current issue.

Sausage, cigarettes, betel nuts and all manner of energy drinks-there's not a lot of subtlety to the typical diet of low-level workers in Taiwan. It's quite the opposite of the gourmet and vegetarian fare that can be found in Taiwan's cities today.

People have to eat to live. In Taipei workers need to work only 12 minutes to buy a kilo of rice. That compares favorably to 21 minutes for a worker in Tokyo or 31 minutes for a worker in Beijing. When it comes to the time spent at work, Taipei workers average 2074 hours a year-less onerous than the 2312 hours that workers average in Seoul, though considerably more than the 1594 hours that workers log in Paris.

For workers who have to spend large amounts of energy at manual labor, diets are less oriented toward elegance than practicality. Their needs have created a unique blue-collar food culture in Taiwan.

Because factory workers spend long hours on production lines with very short lunch breaks, they've got to eat fast. Consequently, the food stalls and stands around factories and construction sites sell ready-to-eat food, such as sticky steamed migao rice, hot steamed wanguo rice cakes, and rice with braised pork. The proprietors quickly apply the sauce and pass over the food, allowing the workers to immediately sit down with warm food and eat in 10 minutes or so. Construction workers can then lie down and take a nap to gather strength for the afternoon's work.

In 1989 Taiwan first let in contracted foreign workers, and then in 1992 the Council of Labor Affairs announced that 7000 foreign domestics would be granted work visas. Since then, foreign workers from Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Cambodia have poured into the country. Along with changing the ethnic composition of the low-skilled labor force, these foreign workers have also prompted an invasion of Vietnamese rice noodles, Thai-style hot-and-sour dishes, Indonesian snacks and other exotic foods into Taiwan's industrial areas and night markets. In districts with many laborers, the streets have seen a clash and fusion of foreign and local food.

The "energy drinks" that laborers can't do without are also highlighted at the museum: Whisbih, Paolyta B and Bullwild energy drinks each have their loyalists. It's estimated that several hundred million NT dollars are spent on energy drinks throughout Taiwan in a given year.

Sausage, cigarettes, betel nuts and all manner of energy drinks-there's not a lot of subtlety to the typical diet of low-level workers in Taiwan. It's quite the opposite of the gourmet and vegetarian fare that can be found in Taiwan's cities today.

Taiwan's workers rely to a great degree on energy drinks to recharge their batteries, and they have come up with various ways of mixing them to make them more effective or taste better. They call these mixed drinks "tau-ei."

In Kaohsiung, one of the first popular tau-ei drinks was made by mixing rice wine with Whisbih or Paolyta B in a 2:1 ratio. Over time the recipe for this "worker's cocktail" has undergone all kinds of modifications. Typically, these variations involve mixing Whisbih or Paolyta with rice wine, fresh milk, sarsaparilla, soda pop of various kinds, Vitalon P soft drink, Yakult, green tea, coffee, Sasaya coconut drink, or Apple Sidra. There are all kinds of differences north and south, and tao-ei culture is also closely bound up with all-out physical effort, strength and work stress. Hence, these mixed drinks have arisen from a big mix of factors.

After walking through the varied holdings of the exhibition space, visitors may find memories from 60 years of Taiwan's labor history being reawakened one after another. The museum prompts them to reflect not only on the history of their own lives, but also to gain a deeper understanding of other people's values, joys and sorrows.

Xie Guoxiong, a researcher at the Academia Sinica's Institute of Sociology, puts it thus: "You can live your working life twice: once in the factories and offices, and once at the Museum of Labor." The pride and resentments of Taiwan's workers, their laughter and tears, have finally gained a permanent safe haven. People can come here to learn about and commemorate those workers who came before them. The museum is sure to be the greatest present opened on International Workers' Day!

Sausage, cigarettes, betel nuts and all manner of energy drinks-there's not a lot of subtlety to the typical diet of low-level workers in Taiwan. It's quite the opposite of the gourmet and vegetarian fare that can be found in Taiwan's cities today.

In keeping with the principle of promoting hands-on experience, visitors to the museum are encouraged to try out old-fashioned sewing machines.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)