Sherry Huang’s Haptic Aesthetics

Representing Pain in After the Last Shadow

Shen Bo-yi / photos Sherry Huang / tr. by Brandon Yen

April 2021

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

From what angle should we look at the dangers faced by women in society? How do artists feel when they participate in crime investigations? How do they translate their personal feelings into shareable empathetic experiences? Sherry Huang’s Last Seen evokes violence, trauma, and a sense of danger. In terms of subject matter and its handling, this series of photographs differs from an earlier series entitled Love Remains, which delves into selfhood, interiority, intimacy, and the practice of journal keeping. In her new work, Huang goes beyond herself to explore other people’s experiences, focusing on the violence experienced by women in society at large, as well as in the privacy of intimate relationships. Last Seen and Love Remains seem to be drastically different in form and methodology, but they are both concerned with close relationships, dangerous conflicts, death and regeneration, and the female body.

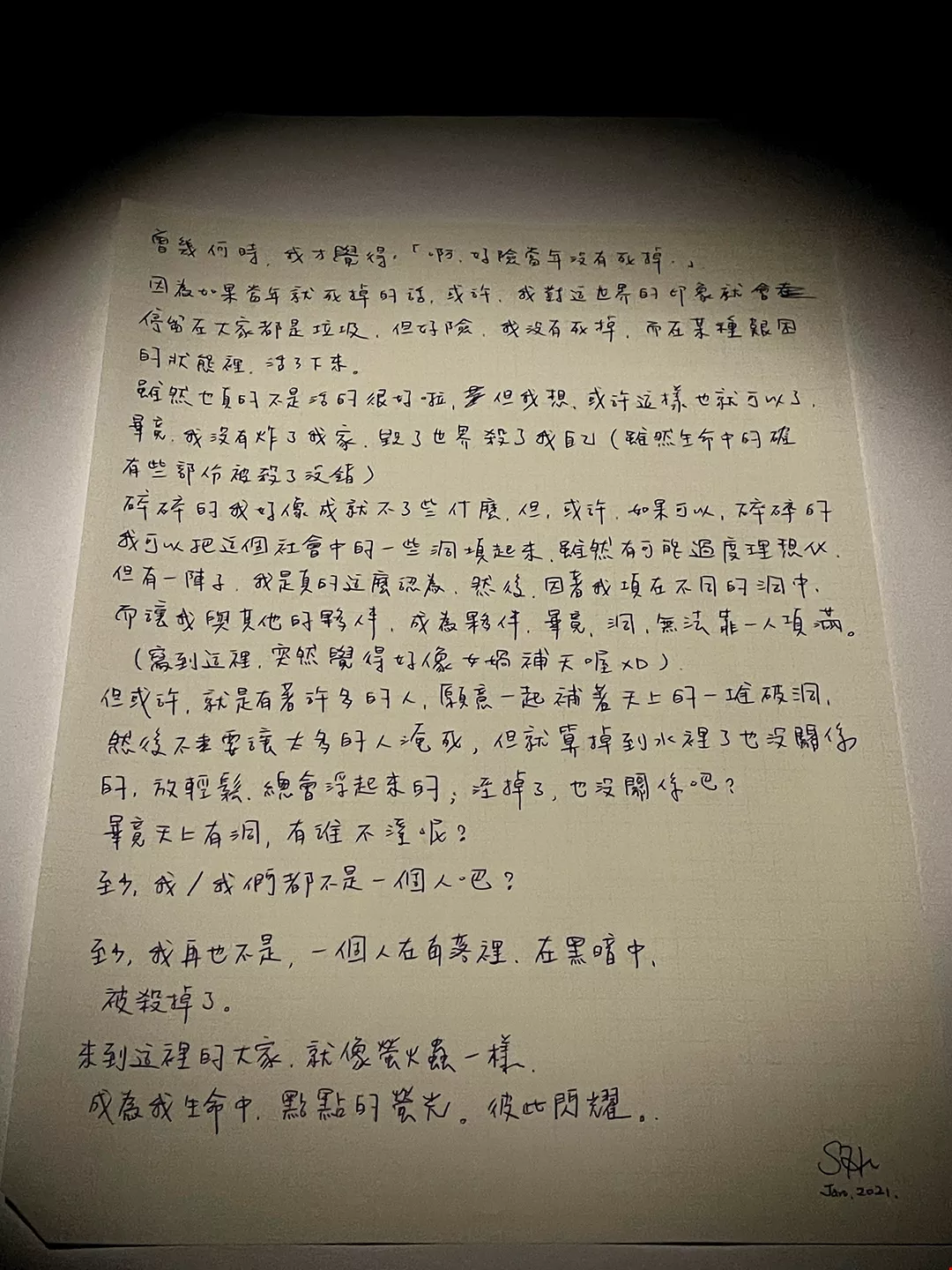

Huang’s solo exhibition After the Last Shadow—mounted in Taipei City’s AKI Gallery in February 2021—expands on the themes of violence, trauma, and pain in Last Seen, using a dialectic method to open up the possibility of healing. Inside the brightly lit “white cube” on the first floor of the gallery, there are three CCTV monitors stacked on top of each other, showing flickering, blurry images of women. On the walls hang two large black-and-white photographs that have been visibly smeared. Ascending to the second floor, we are engulfed by a dark and strange sense of space. Scattered on the floor are several CCTV monitors, again displaying fuzzy figures of women. The electric cables of the monitors are exposed, hanging here and there across the space. Again, we see large-scale photographs that bear clear signs of damage, but here they are interspersed with smaller, irregularly spaced pictures. Finally, the third floor offers fewer visual symbols, and in this dark space we are invited only to listen to certain sounds and to peruse a small number of documents.

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Evoking danger

The blurry negative images on the monitors were collected by Huang herself from surveillance camera footage: they show “last-seen” images of many women shortly before they fell victim to intimate partner violence (IPV). The smaller pictures dispersed across the walls are photographs she took when visiting the crime scenes. As for the smeared large photographs, she took these at locations that were highlighted by police as being particularly dangerous for women and children; Huang inflicted extreme violence—akin to knife attacks, gunshots, and strangling—on her photographic film. The third-floor area of sounds and documents draws on her interviews with two survivors of IPV, narrating and reflecting on their traumatic experiences.

In addition to knowing how the images were produced, we should not neglect Huang’s deployment of the exhibition space. The haphazardly hanging electric cables of the CCTV monitors resonate with the traces of violence displayed in the images. We find ourselves in a dangerous and smothering atmosphere, as if besieged by an indefinable force of chaos and violence. Furthermore, almost all the small monitors on the second floor are placed at our feet, far below eye level, so we need to squat down to take a closer look at the “last-seen” images of the women. Finally, the imageless audio zone dispenses with the visual clues to pain observed in the other sections of the exhibition. Here we are forced to actively listen to the survivors’ own words in the wake of their traumatic experiences.

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Not merely bystanders

Let us return to the visual images. Unlike news stories that satisfy appetites for sensation by directly presenting victims’ conditions and experiences, Huang’s images are mediated, and viewed through an ambiguous veil. For example, both the negative-image footage and the violence inflicted on the photographs interfere with our perceptions and plunge the images into a state of uncertainty. This texturing of the two-dimensional images creates a haptic visuality, and it is this process of mediation that detaches Huang’s images from a problem inherent in photographs of trauma: the ethical issue of “observing other people’s anguish from a distance.”

In other words, if the media keeps transmitting images that dramatize the anguish of victims, this can induce apathy or even a self-congratulating mentality in the audience: “Thank goodness it happened to them, not to me.” Conversely, by mediating her images, Huang brings us back to the processes whereby the victims’ stories unfolded, rather than merely showing us the results of the crimes. This methodology helps us further contemplate the structural issues underlying the events and the images.

In my view, Huang does not merely wish to showcase the dangers faced by women in our society or one-sidedly condemn male violence within intimate relationships. More than that, through her creative work, she recalls and accentuates the strong feelings she experienced when she participated in crime investigations. For example, we are unsettled by the violence wrought on her photographic film and the traces of crime that she exhibits. Interestingly, the non-visual utterances in the final zone of sounds and documents serve a contrastive purpose, plucking us from an unfathomable dark pit and raising the possibility of redemption and healing.

Empowered by pain

After the Last Shadow introduces us to women’s pain and trauma from a complex perspective. Far from merely subjecting pain to an intellectualized version of sensation-seeking (like the news media), Huang reinserts pain into an experiential process by situating it in human bodies, physical materials, and the exhibition space itself. Huang’s recourse to tactile sensibility also distances us from the crude binaries entailed in the media’s predominantly visual representations. It brings us back to our bodies’ intuitive experiences while also reminding us of those fragmented, fragile, incomplete, and intimate bodies in Love Remains. Huang’s After the Last Shadow distills the experiences of female victims, shines a bright and steady light on their traumas, and then translates their pain into a power that enables people to be healed of their wounds and face up to the future.

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

定稿-1@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)