(Drawing by Lee Su-ling)

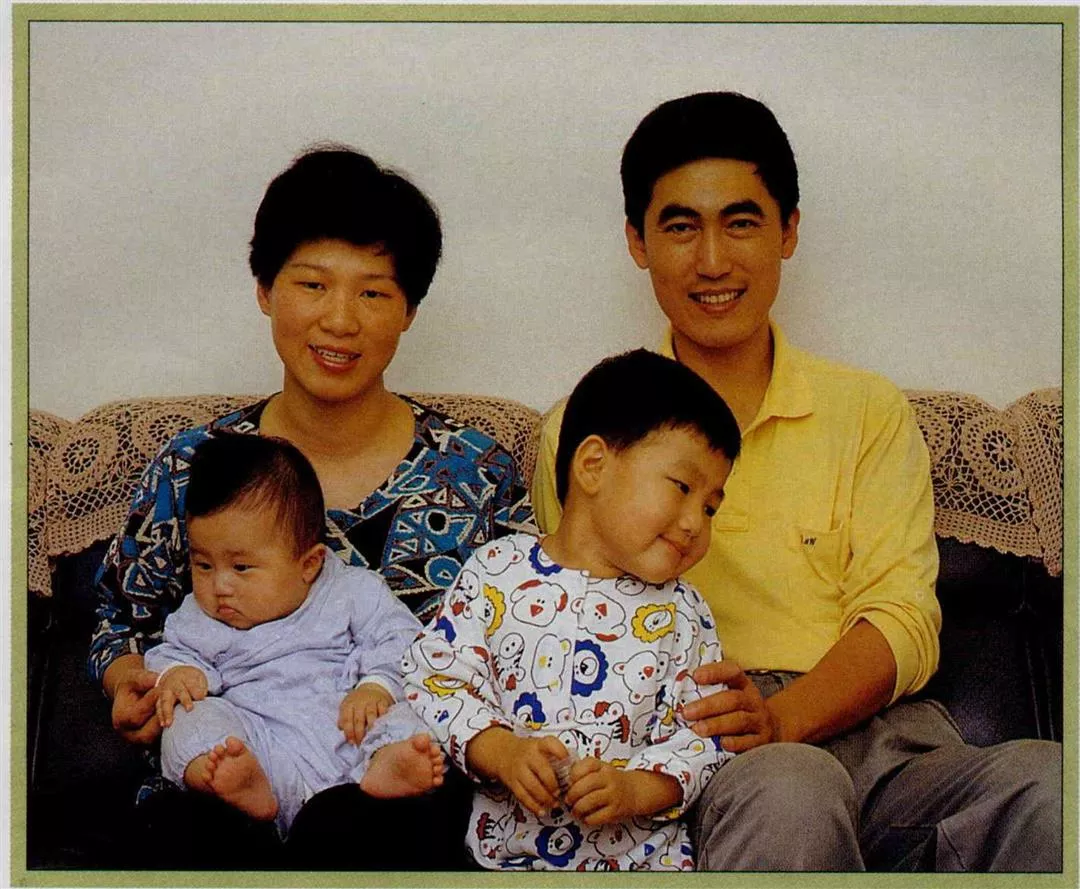

In Taiwan, there are some interesting nicknames for the ethnic subgroups: In general, Taiwanese (or ben-sheng-jen) are called "yams" while those from other provinces (or wai-sheng-jeu) are called "taros." The only thing is that after decades of contact and interaction, there is no longer such a clear distinction between yams and taros. In fact, there are more than a few "yaro households" composed of the two together. How do these "yaro households" differ in their thinking?

One theory has it this way:

During the Japanese occupation period in Taiwan, some Taiwanese went to the mainland to do business. Because Taiwan's shape is similar to that of a sweet yam, they called themselves "yams." After the government moved to Taiwan in 1949, they brought many "provincial outsiders" (wai-sheng-jen, of whom most were military personnel) who were different from local Taiwanese. Later, in the military, there naturally arose another plant-based nickname which could be the counterpart to the yam: old soldiers from the mainland were thus called "old taros." Thereafter, taros became a synonym for those from provinces other than Taiwan.

Before coming over the Taiwan Strait, all those on the ships were "provincial outsiders" to each other, since they came from many different provinces. But once they came to Taiwan together, they were all called "taros" by local Taiwanese. (The fact that Taiwanese see all those from mainland provinces as a collective group accounts for the fact that wai-sheng-jen, which literally means "person from an outside province," is often translated as "mainlanders" in the context of Taiwan.)

What do you get when You cross a yam and a taro? A "yaro"!

Do Taiwanese all know ninja skills? :

There is by no means any academic distinction or foundation for the so-called taro and yam differentiation. The distinction between "other provinces" and "one's own province" is not completely logical. It's just that once this began, it became quite a popular way of speaking among the common people.

But it's also true that taros are to some extent different than yams. Thus, for example, the yams had heard that "the taros love to eat garlic, hot peppers, and dog meat," "taros all take better care of their wives," "taros have very sharp and short tempers," and so on. Among the taros, it was said that "the yams are mostly male chauvinists," the yams are "real country bumpkins," and the like, and even that because Taiwan had long been governed by Japan, there were some who said, "these yams all know ninja techniques."

Regardless of the accuracy or error of these stereotypes, the yams and the taros have been living side by side for 40 years. Many have also set up "yaro households." As a result, everyone has gradually discovered: "It seems it's not true that all the taros love hot peppers," or "it's ridiculous to say that all these yams know ninja techniques." Just as it's not true that all mainlanders are members of the Kuomintang, it is also not true that all Taiwanese cast their votes for the Democratic Progressive Party.

There is one yaro household in which the husband is from Hopei and the wife is a Hakka from Miaoli County in Taiwan. Ordinarily the two have very deep feelings for each other, but in one situation they will draw a clear line because of their own different past experiences. Because the wife had a Japanese education in her childhood, Japanese manners and customs were part of her way of thinking, she loves Japanese music, and she is devoted to the idea of travelling to Japan. Her husband had done underground work during the War of Resistance Against Japan and was tortured by the Japanese military, so he has a profound hatred toward Japanese.

Each time the wife puts on Japanese songs, he can't put up with it, and begins to loudly sing, "Take the knife and cut off the heads of the devils. . . " and other such tunes to express his protest.

Of course, third parties needn't worry. The abovementioned yaro household hasn't suffered a change in sentiment because of this. They very much understand that "songs are just songs, but family is family." They never can resolve the musical problem, but in the several decades they've been married, they haven't been seen arguing just because of this.

"Yaro households" combine eating customs from different regions of China. Here Taiwanese clear congee is served with Shantung steamed bread.

Cross-breeding yams and taros:

It seems there may be some contradictions, but overall life goes on.

Forty years ago, probably no one thought that today Taiwan would have these kinds of yaro people!

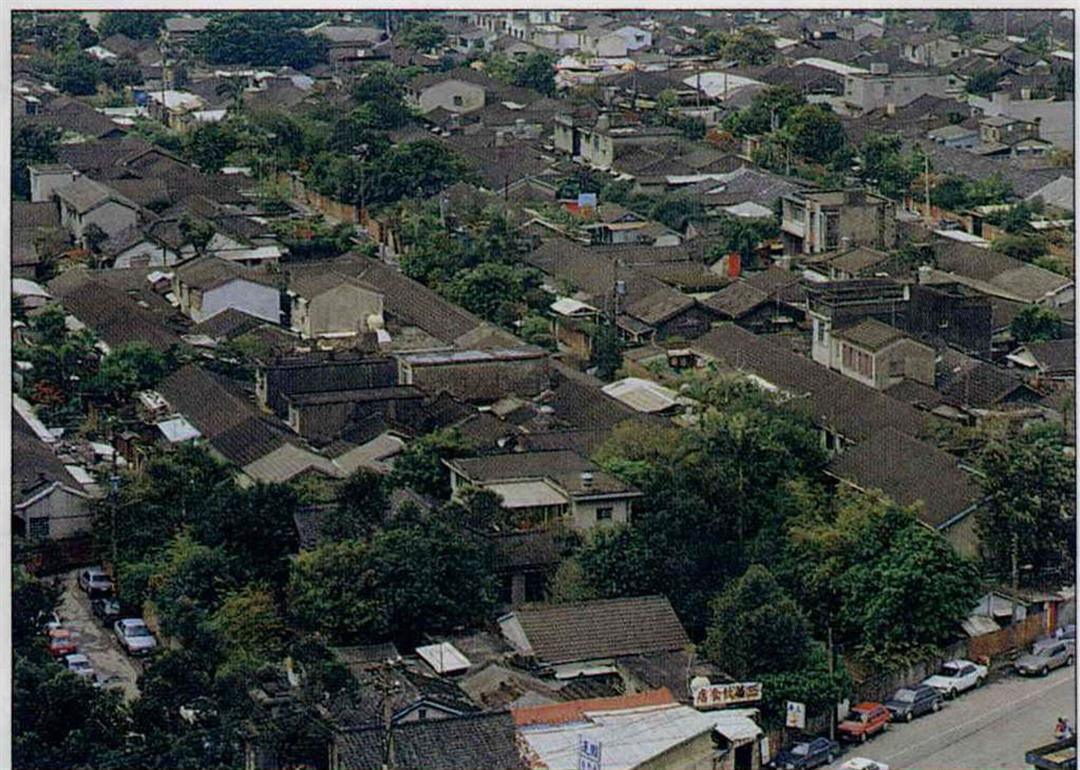

In traditional Chinese society on the mainland, communications and transportation were extremely restricted. To go only 15 miles from home was considered going to a "strange land." Before and after 1949, many mainlanders who followed the military in its retreat hadn't even imagined in their dreams that in some corner of the globe there was this place Taiwan.

According to scholarly estimates, from 1948 to 1950, there were about 9l0,000 civilian and military mainlanders who followed the government in its withdrawal, accounting for about 14% of the then population in Taiwan. They came to Taiwan because of the war, and few did not dream of returning to their homes. Still, as the days passed, the old village became more distant. They had no choice but to make other plans, and the most common was to get married in Taiwan. "Perhaps when returning home at some future time I will have a wife and children to accompany me," they thought.

Moreover, because the nature of this immigration was political and military retreat, the ratio of men to women was not balanced. There were about three times as many men as women.

The imbalance between men and women meant that there was no way to have full intermarriage among the first-generation mainlanders, whose social, cultural and linguistic backgrounds were relatively close (despite the fact that they saw each other as "provincial outsiders"!). Therefore many people married with natives of Taiwan. But since in the early years after retrocession there were many gulfs between Taiwanese and mainlanders, one hears of conflicts, of which the "February 28 Incident" of 1947 is just the most famous example. The marriageable mainlander males and locally born women were seeking partners, but because of cultural and psychological differences, many first-generation yaro marriages were in fact less than happy.

Early on mainlanders called military dependents villages their own; with the gradual influx of Taiwanese wives they became the foundations of assimilation. (photo by Vincent Chang)

Buy a wife and make yourself a family:

In a short story describing how an old soldier in the early days took a wife, the writer Ku Ling described the tragedy of the weakly competitive old mainlander soldiers in the marriage market . In this story, entitled "Dragon Chang and Tiger Chao," Chang and Chao had been soldiers all their lives. The two were fast friends, and after following the army to Taiwan stayed on as soldiers. In order to satisfy their sexual needs, the two went in together to buy a girl, with Dragon Chang using his name as the official husband . . . .

"Purchased marriages" often occurred among the first generation of mainlander soldiers. Because their economic situations were poor, many of the local women that they married were marginal in Taiwanese society, such as widows, the handicapped, or aborigines. Because purchased marriages lacked any emotional foundation, this led to social tragedies like wives fleeing home or children growing up with unsound characters.

First-generation marriages between Taiwanese and mainlanders were mainly a product of the environment. Mainlander males had little choice. Thus you can't even talk about the two groups willingly coalescing, and there were also many problems. Yet there were also first generation Taiwanese and mainlanders who came together because of mutual affection. Because society at that time did not approve, the result of passing through many obstacles was ironically to make the marriage even more sweeter.

Hsiung Shu-hwa's father is from Hubei, and her mother is from Pinghsi Rural Township in Taipei. When the government moved to Taiwan, father Hsiung followed them across, and went to work in Pinghsi. There he met his future wife. They fell in love and were married. Before the two wedded, there had never been a case of a marriage between a Taiwanese and a mainlander in Pinghsi. In order to avoid being given the old runaround, the husband brought the local police chief along when he went to ask his wife's family for her hand in marriage. "Country people are afraid of officials. and when they saw the police chief at the door, my grandfather didn't even dare draw a breath, and gave his permission immediately," laughs Hsiung Shu-hwa as she relates the story as her mother had told it to her.

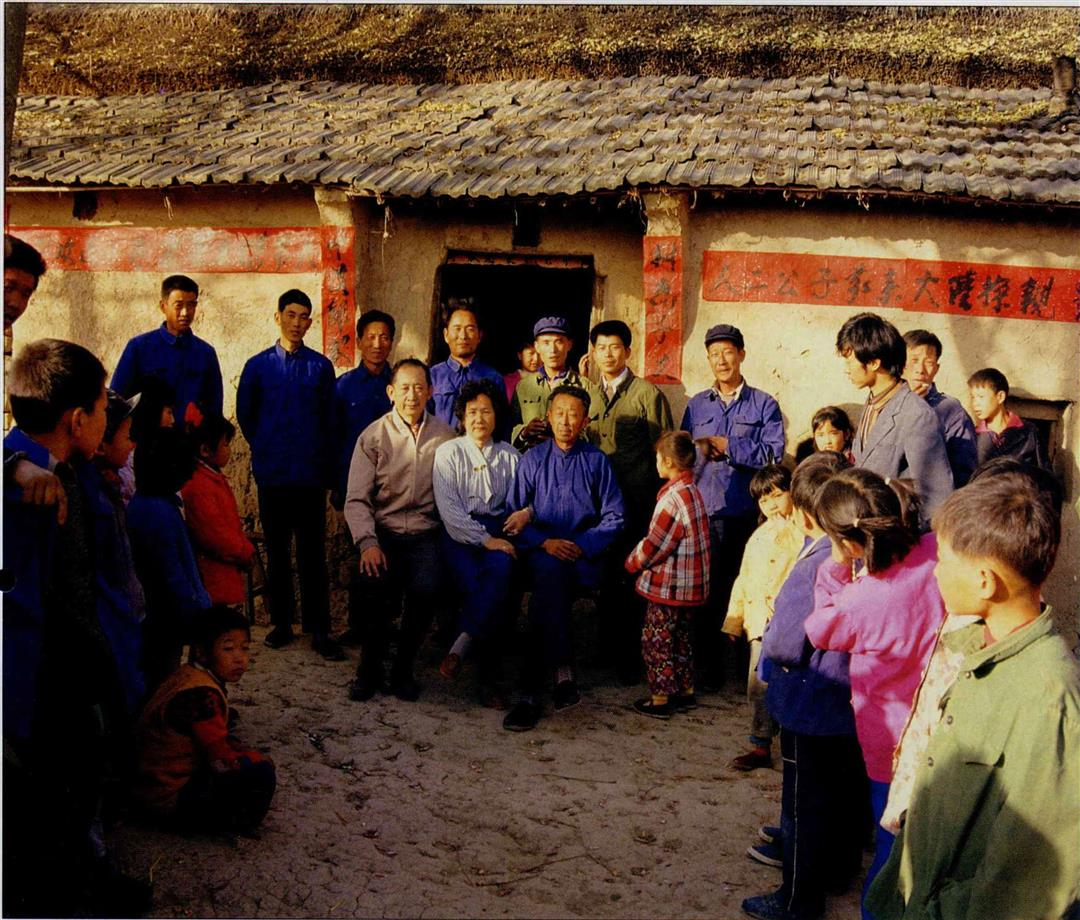

Forty years later, a "provincial outsider" returns to his old home in the mainland and finds himself a "provincial outsider" yet again.

Do mainlanders really treat their wives better?

After the Hsiungs were married, because theirs was a love match, their mutual affection was very deep. This was taken in the locality of proof of the theory that mainlanders take better care of their wives. As a result, there was a sudden fad for marrying wai-sheng-jen. Most of Mr. Hsiung's mainlander friends found their life partners in Pinghsi.

According to the third survey of the Academia Sinica's "Social Trends in the Taiwan Area," taken in 1992, as well as the data acquired for the "Basic Survey of Social Change in the Taiwan Area," beginning in 1944 the percentage of marriages between Taiwanese and malnlanders was between 16 and 19% . Taking marriages between Taiwanese and those of other provinces, for example, in the first generation of cross-marriages, the percentage of such marriages involving a male Taiwanese and a female mainlander was 1.5%. But the rate for mainlander men and locally born women was 7.4% of the total marriages. This confirms the belief that first generation male mainlanders had to marry local women because of an imbalance in the marriage market.

But by the second generation, the marriage rates of ben-sheng-jen males and mainlander females and of Taiwanese women with wai-sheng-jen men were 5.3% and 5.2% respectively. The rates are thus extremely close, which indicates that there has been less pressure on the second generation to match within the social structure, and there is a somewhat greater possibility of cross-group combinations.

In contrast to the extremes of the first generation, matches in the second generation are mostly based on affection. However, because backgrounds are somewhat different, and because of the need to face the whole first generation clan after marriage, there have still been some problems arising from differences in provincial origin.

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Burn away the melancholy for the old hometown! He has already set down firm roots in Taiwan soil.

When yams and taros meet:

Miss Li is Shantungese. She is forty this year and has been married for ten years. Because she grew up in southern Taiwan, she speaks Taiwanese very fluently. Before she got hitched, she figured that if she married a Taiwanese, at least linguistically there would not be any problem. Little did she expect that her marriage partner wouldbe a Hakka (a subgroup considered part of the "Taiwanese, " but of Hak-kanese rather than, as the majority of ben-sheng-jen, of Fukienese origin), and she couldn't understand even one sentence of that dialect. And although her husband's family all understand Taiwanese and Mandarin, when they get together they are still accustomed to conversing in Hakka. "When I had first married into his family, I felt like I was a foreigner," she says. That old feeling of being excluded was really hard to take.

TV hostess Fang Ti is Fukienese. Her physician husband is from Shulin in Taipei County, and she has come across a similar situation.

In the past when her husband's family got together, this Mandarin speaker often couldn't get a word in. She recalls that this simply couldn't continue, so she had to devote herself to studying Taiwanese. Over the past several years, she has become able to use Taiwanese on TV to host programs.

Some problems are only discovered after marriage, but there are also frictions that can arise before marriage. Before a certain mainlander girl was going to marry into a Taiwanese family, the husband's family insisted that only a certain number of gift cakes would be an auspicious number. But the father of the bride did not feel this was necessary, and even said thoughtless things like "we don't have this custom in the mainland" and "in the mainland we feed these kinds of cakes to dogs. " As a result, although the two families still went through with the marriage, there has been a certain distance.

According to research by Wang Pu-chang, an assistant researcher at the Institute of Ethnology at the Academia Sinica, without controlling for other variables, there are definitely more disputes in cross-group households than in households in general. No matter whether in attitudes toward education of the children, methods of handling the family finances, or daily habits, there are differences in all areas. There is even a higher incidence of arguments than in households where both partners come from the same subgroup. Among the sample of same-subgroup marriages, 6.9% had considered splitting up; the corresponding figure for cross-group marriages was 8.6%.

Capable in both Taiwanese and Mandarin:

But when you turn it around, in other respects, yaro households have the upper hand.

Yaro families are usually bilingual. In a modern society where the more languages one knows the better, yaro children often have linguistic advantage. Miss Yang is a senior magazine reporter. Because she belongs to a yaro household, she is capable in both Mandarin and Taiwanese. She is very well versed in the subtle dynamic produced by the different backgrounds and cultures of her parents, which is quite an advantage for her when doing a report. In particular, when she has a topic that requires her to go to southern Taiwan, she is often much more able to get a sense of the feelings of the interviewees.

After being married, Hsiung Shu-hwa left her children in the care of her Taiwanese mother. Thus the children were already fluent in Taiwanese by he age of two. But when the kids returned home, they were in the habit of speaking Mandarin with Mom and Dad. "After they would hear children's stories at Grandma's, when they came home not only could they give a rendition in Taiwanese, they could even translate them into Mandarin for us, "says Hsiung Shu-hwa in a satisfied tone.

Fang Ti's child is also a Mandarin-Taiwanese bilinguist. Add to that that she studies English in kindergarten, and she is already "trilingual."

According to Wang Pu-chang's research, the generation of children produced by cross-group marriages has a lower "provincial identity consciousness" than those of purely Taiwanese or mainlander families. "This holds regardless of whether you look at it from statistics on provincial identification or political attitudes," he notes. That cross marriages are helpful to inter-group assimilation is because, in theory, they are a voluntary, two person joint effort, which is the most difficult method to achieve inter-group fusion. Other types of blending, such as cultural, psychological, attitudinal, social, behavioral, or citizenship, can all, on the other hand, more or less be achieved through designed techniques.

Confused yaros:

Tsai Ling-yi's father is Fukienese and her mother is from Tainan. When you ask her if she feels like she is Taiwanese or mainlander, she in fact just feels confused. Her official identity card says mainlander (after her father), yet she most often uses Taiwanese as her language, and she also has no feelings toward mainland China whatsoever. Therefore she describes herself as a "half and half."

Today, as provincial consciousness is intensifying, the yaro households feel most helpless. Legislator Chou Chuan's father is a mainlander and her mother a Taiwanese, so she is classified as a mainlander, and moreover is seen as part of a "mainlander clique" politically. Chou Chuan feels extremely angry about this: "Don't ask me to choose sides." Is it possible that yaro people can choose to love only their mothers or their fathers?

Most yaro people don't want to be labelled. And when politicians try to express their feelings, the ordinary yaros turn them right off. "Don't ask me about the issue of provincial identity, I'm not interested," says Shen Wen-ying, a yaro teacher.

A new kind of hometown melancholy:

Hsueh Ching-wu had been hearing his father describe "beautiful rivers and mountains, my mainland hometown" from the time he was small When he was little he perhaps had some fantasies, but when he got a little older and he knew that sanitary conditions there were not so good, the fastidious Hsueh lost all interest in "the old hometown." Despite the fact that he often travels abroad, he rarely has a notion to go to the mainland. "We'll talk about when they've got indoor plumbing!" he proclaims. Now studying abroad, what he constantly misses are the streets of Taipei. Although his ID has him classified as being from Jiangsu, his "hometown melancholy" is obviously for a place quite different than his father's.

After more than 40 years of growth in Taiwan, whether it be in outward appearance, living habits, or value systems, it is extremely difficult to distinguish ben-sheng-jen and wai-sheng-jen. Some differences in fact are merely stereotypes. "Who says mainlanders invariably eat hot peppers? My wife is Chekiangese and won't touch hot food." Or, "Mainlanders love to eat beef? What a joke. Chinese people have never loved eating beef, " says legislator Ju Gau-jeng, who has taken a Chekiang wife. In fact, many stereotypical differences between Taiwanese and mainlanders are completely groundless.

The taros have set down roots here. After marrying a yam wife, they have learned to like rice congee and have taught their wives to eat fried bread and oily bread sticks. The only problem is when the "little yaros" get picky and insist on McDonald's. "Ridiculous! How is it that a yam and a taro can give birth to a French-fried potato?" sighs the father of one little yaro.

Today's Taiwan is truly a special place which brings together unique features of all places in China, yet it has also produced a style different from any of those places. In Taiwan you can see Szechuan restaurants everywhere, but the food isn't as ludicrously hot as true Szechuan cuisine. Although they can't take things too spicy, Taiwanese have learned to accept things a bit spicier from Szechuanese, while Taiwan's Szechuan natives no longer eat food as hot as in the past because of changes in the living environment and climate. Thus, in terms of living habits, everyone is adapting to the locality, food is getting all mixed up, and even the people are changing.

Twice a "provincial outsider":

"In the past few years I have gone back to the mainland to visit relatives. But in terms of living habits, it's just like the experience of being a 'provincial outsider' as I was the first time 40 years ago arriving in Taiwan," says an old mainlander soldier returning to Taiwan after visiting the old hometown. After being accustomed to life in Taiwan, it is difficult to get reaccustomed to living in the mainland which makes these people wai-sheng-jen yet again.

Premier Lien Chan is from Tainan, and his wife Fang Chiung is a mainlander who was born in Chungking. The couple have four kids. When you ask them if there is any trace of provincial differences in their home, Fang Chiung has a hard time answering because it's really quite difficult to find a problem where there is none. She considers that although she is a mainlander, she does not like the mainland as it is at present, so she absolutely doesn't miss the family hometown. And there is no provincial differentiation. "Although traffic in Taipei is a mess, I still prefer the place that I have lived for decades." She describes herself as a Taiwanese Chinese.

Liao Chung-shan, a professor at the National Ocean University, is a native of Henan Province. At the age of 15 he came with the military to Taiwan, and even today his Taiwanese is not very good. His wife Lin Li-tsai is from Kaohsiung. The pairing up of these two people involves no tale of passionate romance. "It was entirely that I had reached the age where I wanted to take a wife, and being alone in Taiwan I could only marry a wife from here. Moreover, my wife is an orphan, and was afraid that if she married into a Taiwanese family she would be looked down upon, so she had the idea of marrying a mainlander without any family burden. So after we were introduced by someone, we got married," says Liao, describing his marriage as extremely ordinary.

The new hometown becomes the old hometown:

Nevertheless, unlike the great majority of mainlanders, Liao Chung-shan completely accepts that Taiwan is his home. He says, "After a long time, the new hometown is the old hometown." He feels that in sentimental terms China is his "natural mother" but Taiwan is the "nursemaid who raised him." After 40 years in Taiwan, he is already a "Taiwanese" who belongs to this place. Therefore, even though he can't speak Taiwanese well, and the husband still likes to eat that steamed bread, none of this affects the feeling between himself and his wife, because they share a common love for this land.

You know? Although Taiwanese call themselves yams and call mainlanders taros, in fact neither yams nor taros are native plants to this soil. It's only that both of them have grown in this earth, so they have become common plants here. As for people, they are like the yams and the taros--having grown on this piece of earth for a long time, the taros become like yams and the yams look more and more like taros, and the two produce little "yaros" through marriage. Can you really say what it is they are?

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)