The Mekong Cultural Hub:

Building an Arts Network for Taiwan and Southeast Asia

Chen Chun-fang / photos by Kent Chuang / tr. by Phil Newell

July 2025

A small wooden hut appeared in a hallway at National Taiwan University of Science and Technology (NTUST) to show films about the Mekong region and inspire greater curiosity about Southeast Asia among students.

In April of 2025, the first Chakto Program for contemporary dance was held in Cambodia. Among those invited by one of the sponsors, the Mekong Cultural Hub (MCH), to be a jury member was theater worker Wu Weiwei, director of Taiwan’s We Art Together Foundation and chairperson of the Performing Arts of South Taiwan Association (PASTA). She described the dance works she saw as being “as dynamic as a tuk-tuk winding through urban streets” and “very moving.”

In October, the MCH will hold the “Meeting Point on Art and Social Action in Asia” in Laos, as it works to bring together arts and culture workers from Taiwan and Southeast Asia to build bridges across Asia.

In May, a collection of short films titled Mekong 2030, produced by the Luang Prabang Film Festival in Luang Prabang, Laos, was shown at National Taiwan University of Science and Technology (NTUST) as part of an event named Voices from Mekong. Made in various nations through which the Mekong River runs, the films depict the coexistence and interdependence between man and nature.

Jennifer Lee, program manager of fellowships and training at the Mekong Cultural Hub (MCH), who ran the Voices from Mekong event, tells us that it was very exciting to be able to feature Southeast Asian arts at a university focused on science and technology. The MCH assists arts and culture workers endeavoring to practice social responsibility, while NTUST encourages students to take sustainable development into account in all their endeavors, making the two a natural match. Speaking the common language of sustainability, they created an encounter between the arts and technology.

Wayla Amatathammachad, director of Thailand’s Prayoon for Art Foundation, shared his thoughts about Thailand’s changing environment and culture at his workshop.

Voices from Mekong

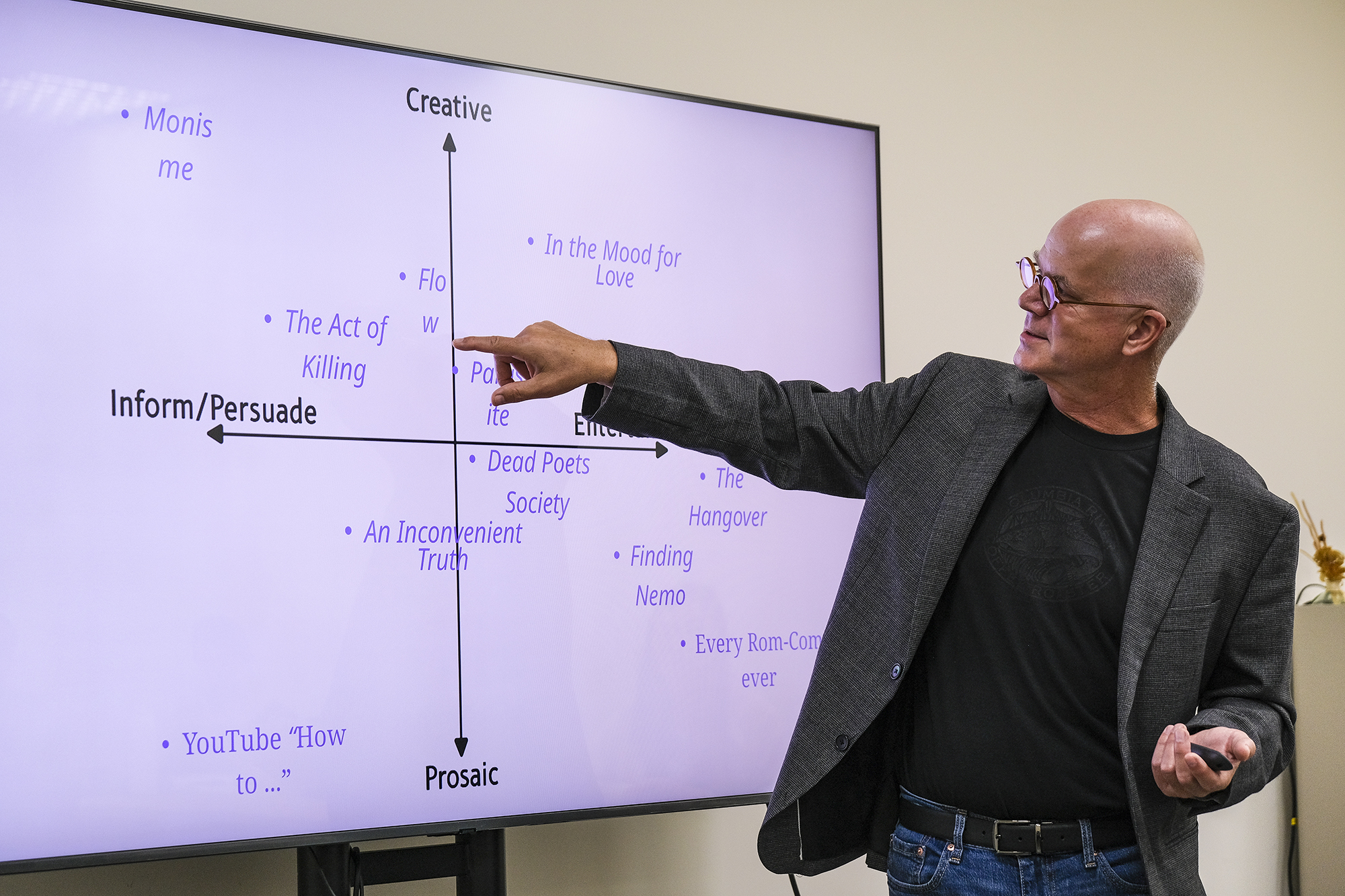

During a workshop at the event, entitled Confluences: Art, Science, and Storytelling along the Mekong, Sean Chadwell, executive director of the Blue Chair Film Festival, showed a number of short films and invited students and faculty to split into teams to play the roles of independent producers, government reviewers, and corporate sponsors. This enabled participants to better understand environmental issues and the challenges facing arts and culture workers in the Mekong region.

At another workshop, called Dancing with Nature: Reinventing Life in Thailand’s Rural Landscapes, led by Wayla Amatathammachad, director of Thailand’s Prayoon for Art Foundation, Amatathammachad shared his observations on Thailand’s changing environment and culture. He also invited participants to write down “keywords” about their own situations and used these to create a relationship diagram, to inspire attendees to rethink the challenges involving the environment, tradition, and society, as well as potential next steps.

US-born Sean Chadwell, executive director of the Blue Chair Film Festival in Laos, speaks about types of cinematic narration at a workshop entitled Confluences: Art, Science, and Storytelling along the Mekong.

The arts as a stimulus to reform

Jennifer Lee says that the MCH is a regional program that was launched when Living Arts International (LAI) set up an office in Taiwan—likewise named the Mekong Cultural Hub—in 2018. The core beneficiaries of the program are cultural workers from Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The core ideal of both LAI and the MCH is to use the arts and culture as catalysts for social reform. Lee notes that LAI founder Arn Chorn-Pond was a refugee from the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia and was adopted and raised in the US. When he later he returned to his home country, he discovered that its traditional arts had been severely damaged by conflict. He then raised money to found LAI, because he firmly believes that arts and culture can help heal a wounded society.

LAI’s connection with Taiwan originated with an invitation for its executive director, Phloeun Prim, to serve as a member of the first Southeast Asia Advisory Committee of Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture (MOC). He networked with Taiwanese arts and culture workers and discovered the potential for building cultural links between Taiwan and Southeast Asia. At the time when LAI was seeking to launch a regional cultural exchange program across Asia, the government in Taiwan was also promoting closer cultural ties with Southeast Asia. Thus, with support from the MOC, LAI opened its MCH office in Taiwan.

Over the past seven years the MCH has offered various training projects, such as one in psychological first aid and one on ethical dilemmas in arts practice. Moreover, once every 18 months MCH holds a “Meeting Point,” bringing together over 100 Asian arts and culture workers each time, while international organizations like the Asia–Europe Foundation are also invited to attend. These are venues where practitioners, policymakers, sponsors, and researchers can engage in dialogue.

At a workshop given by Wayla Amatathammachad, participants wrote down keywords about their situations to spark ideas about possible future actions.

NTUST worked with the Mekong Cultural Hub program to bring Southeast-Asian arts and culture to the campus and create encounters between the arts and technology.

Linking Asia’s creative capabilities

The links forged through the MCH are deep and complex, and are not limited to cultural exchange.

Wu Weiwei, who took part in a Meeting Point event in Vietnam last year, says that her attendance there not only enabled her to learn about the common Asian experiences of Taiwan and Southeast Asia, it also allowed her to form partnerships with creators from the Mekong region.

The MCH curated a creative action program involving Wu and a visual artist from Vietnam, a puppet theater artist from Thailand, a choreographer from Laos, and a sound artist from Myanmar. Following prior discussions online, they each brought spices and special cloths from their own lands with them to Hanoi.

Wu says with a laugh that she brought braising spice packs and Hakka printed cloth, while other artists brought items such as baxianguo herbal candy, bay leaves, and cinnamon. They explored the similarities in their use of spices and ultimately created a performance that blended spices, textiles, and other cross-cultural elements.

In an open space, the performers danced while interacting with draped textiles hanging down from above. This combination of cloths from different nations symbolized the blending of multiple cultures. The performers invited the audience to connect the pieces of cloth together randomly, and tie spices to the material however they wished. The result was a collectively formed cross-cultural work of fabric, music, seasonings, and human bodies.

This fleeting yet profound cocreation deepened the sense of team spirit between the artists involved. After returning home they stayed in contact, and even formed an informal creative alliance called the Grassroots Gossiping Group (GGG), a name inspired by the “Perspectives from the Grassroots” theme of the 2024 Meeting Point in Hanoi.

Wu says that the GGG is currently considering a second cocreation project, this one on the themes of “colonialism” and “motherland.” They are looking back over their national histories and thinking about the relationships between people and the land. Most regions in Asia underwent colonization, and this experience not only has shaped each country’s cultural background, it became the GGG’s common creative language.

Although they are still seeking funding for this second work, the artists have continued to stay in touch online and through in-person visits. “We all feel that this kind of multinational creative work is all too rare and really expresses the power of Asia.” Wu explains. Because the members of the GGG are all from different countries, and each has their own space to rehearse and perform, they are considering a mobile touring performance model. The work might first be shown in Taiwan, then head to Thailand, Laos, and elsewhere, and if the opportunity arises, even Europe. As Wu describes it, their collaboration is not just cultural exchange, but a collective act of speaking out by Asian artists.

提供.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

The MCH held an event at Taipei's Huashan 1914 Creative Park on the theme of “A Friend of a Friend” to showcase the results of MCH-sponsored interactions between Taiwan arts and culture groups and Southeast Asia over recent years. (courtesy of MCH)

“A Friend of a Friend” may sound mundane, but it refers to strong and enduring linkages.

Mr. Hoang Nguyen and Ms. Ngo Tran Phuong Uyen).jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

The Mekong Cultural Hub (MCH) held a Meeting Point in Vietnam in 2024 to enable artists from various countries to share ideas and inspiration. (courtesy of Mr. Hoang Nguyen and Ms. Ngo Tran Phuong Uyen)

Jennifer Lee, program manager for fellowships and training at the MCH, is building bridges for Southeast Asian arts and culture and is a strong supporter of cultural workers.

Sparking local vitality

“The MCH does more than just build platforms for arts exchanges; it is weaving a broad and dense network,” says Ku Shu-shiun, associate professor in the Department of Cultural and Creative Industries at National Pingtung University. The MCH links artists through cultural exchange programs, she explains, and these connections not only produce creative sparks during the programs, but may inspire broader enthusiasm that enables the arts to have a wider impact.

Ku, who has twice taken part in MCH programs, is acutely aware of this. A specialist in the study of cultural policy and former CEO of the National Cultural Congress, she not only understands the ideas and expectations of the arts community, but has long been concerned with how to implement cultural policies at the grassroots level.

Ku is extremely enthusiastic about cultural policy and the cultural and creative industries, but she has noticed that most students feel that cultural issues are remote from their lives. She has often asked herself: How can the gap between cultural policy and daily life be narrowed?

In 2019, Ku was invited by the MCH to attend a workshop in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. This was her first visit to Southeast Asia, and she saw first-hand how Cambodian creative artists used all available options to make the best of the limited cultural resources available there. “The powerful vitality exhibited in the local arts and culture scene was very inspiring to me.”

With this inspiration in mind, she took advantage of the fact that National Pingtung University was promoting “university social responsibility” to lead her students to the grassroots level of society. She led students into Fangliao Township to work with local youth to make a survey of local cultural and historical resources, hold a public forum, and organize community concerts. She says with a smile that the concert series has entered its fourth year and has become a popular event that community elders look forward to.

Even more exciting is the fact that one of the students who went into the community with Ku back is the day now works at the Lovely Taiwan Foundation, a long-term promoter of local creativity, and is involved in organizing an annual event in Chaozhou Township that conveys the power of arts and culture to the locality. All of this can be traced back to the inspiration Ku received on her trip to Phnom Penh. She concludes: “The MCH allowed me to see the power of arts and culture, leaving it up to everyone to see what they could do with it.”

Last year the MCH held an event at the Huashan 1914 Creative Park on the theme of “A Friend of a Friend” that featured the achievements of the connection and exchange built between arts and cultural workers from Taiwan and Southeast Asia through MCH programs. Jennifer Lee says with a chuckle that “a friend of a friend” sounds very mundane, but it has a very significant meaning. When we become friends, we better understand and care for each other, and we also introduce subjects that interest us to our friends. The effects can be very powerful.

Sean Chadwell came from Laos to Taiwan for the first time at the invitation of NTUST to attend a workshop, and has made a promise to Taiwan that he will come back for the East Coast Land Arts Festival. Meanwhile, Thailand’s Wayla Amatathammachad continues to study schools in Taiwan’s indigenous communities in hopes of finding ways for people to peacefully coexist with nature. With Taiwan as its base, MCH is building a network for cultural exchange among Asian arts and culture practitioners—expanding the reach of the arts and catalyzing the emergence of a more inclusive and sustainable world.

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

After Meeting Point 2024, Wu Weiwei (lower right) and artists from Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar and Laos formed the Grassroots Gossiping Group to draw attention to the power of Asian art. (courtesy of Wu Weiwei)

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Artists from various Asian nations shared the similarities in their use of spices and found a common creative language. (courtesy of Wu Weiwei)

.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Wu Weiwei (front row, third left) was invited to serve as a jury member and consultant for the Chakto Program of contemporary dance in Cambodia. She also shared her experience organizing small-scale arts festivals in Taiwan and promoting them internationally. (courtesy of Cambodian Living Arts)

-13a.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

National Pingtung University held a citizens’ cultural forum in an effort to help people at the grassroots level connect with cultural policy. (courtesy of Ku Shu-shiun)

-13c.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

A workshop held in distant Cambodia became the spark behind community concerts in Taiwan. (courtesy of Ku Shu-shiun)

Ku Shu-shiun (front row, second from right) brought her students to Fangliao Township in Pingtung County to engage in grassroots cultural activism, including the holding of community concerts, which have become important community cultural events. (courtesy of Ku Shu-shiun)

Mr. Hoang Nguyen and Ms. Ngo Tran Phuong Uyen).jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Asian artists worked together to use spices, cloth, music, and physical movements to collectively create a multicultural work of art. (courtesy of Mr. Hoang Nguyen and Ms. Ngo Tran Phuong Uyen)