A Learning Experience for Everyone

Jackie Chen and Teng Sue-feng / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Phil Newell

February 1995

Here no one tells you to wear your shoes into class, and you don't have to sit quietly in your seat. Morning classes lest only until 10:00, and there's even a snack period.

This is not a nursery school, but an educational experiment currently being undertaken by various primary schools in the greater Taipei area. Compared to past pedagogy of "the teacher talks and the students listen," the biggest difference is that the children seem happy to be in class.

The Forest School, the Caterpillar School, "open classrooms," "kindergarten-primary school linkage," "experimental classes in modern education," "innovative evaluation methods," "outdoor education" .... Right now about one out of every six of the 350 primary schools in the greater Taipei area is undertaking instructional reform.

In the past, so-called "experimental classes" were only for the exceptionally intelligent or those gifted in the arts. The focus of this wave of experimentation is the ordinary student. The classes go by different names, but the goals are similar. As Cheng Tuan-jung, principal of the Chu Kuang Primary School in Panchiao, says, in educational reform, "all roads lead to Rome." All these experiments are aimed at giving the children "an even better learning environment where they can learn more joyfully and with more initiative."

One thing all these programs have in common is that there are fewer students per class. There are 20-30 pupils in the typical experimental class in a public school, as compared to the traditional 30-46 pupils. The private Forest and Caterpillar academies combine students of different ages (such as putting fifth and sixth graders or third and fourth graders together) into classes of ten or so kids.

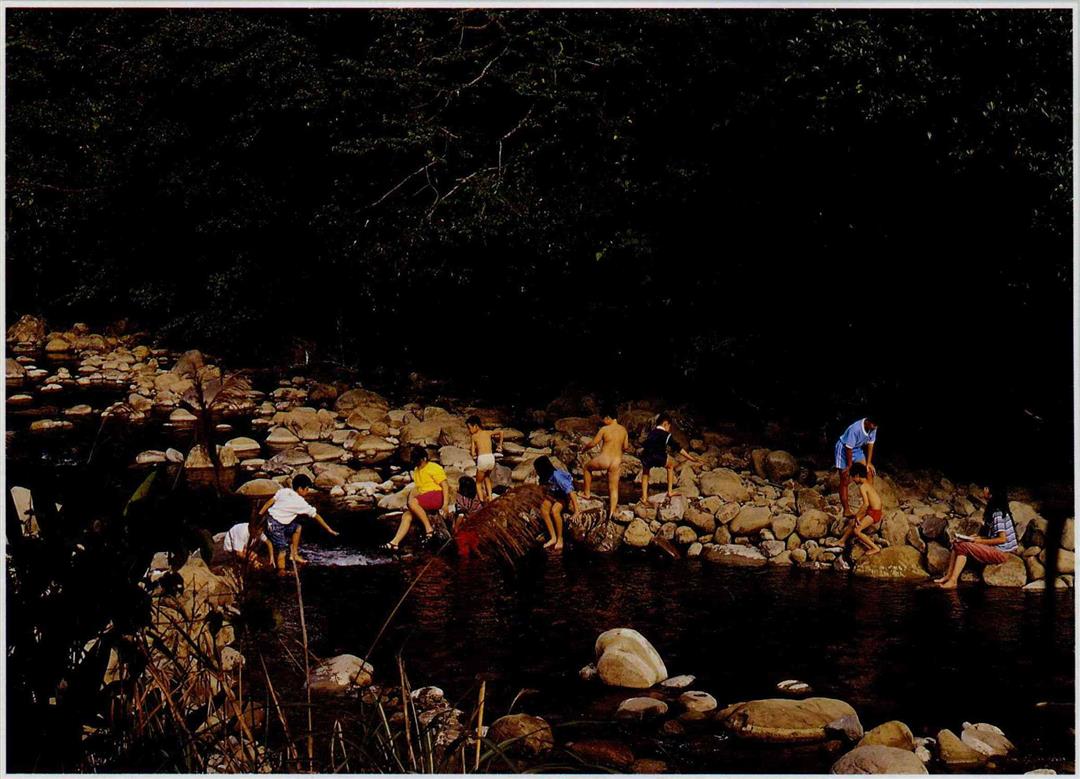

The sun is shining, the stream water glistens. The older children join the younger, presenting a lovely picture of life at the Caterpillar School.

Not according to the book

Different paths, similar goals-all reforms are aimed at getting the children to "study happily." Of these experiments, the Forest and Caterpillar schools employ the greatest variety of teaching methods. Although these two institutions are more adventurous than other primary schools, they have by no means abandoned textbooks. It is just that they do not necessarily follow the textbooks, but supplement them with a lot of extracurricular materials.

Take for example the teaching of the history of Taiwan. The children in the Forest School get to watch films like The Silent Hills (about Taiwan's now defunct mining industry) or listen to radio dramas like Wu Leh-tien's The Legend of Liao Tien-ting (about a Robin Hood type hero of the Japanese occupation era), getting a feel for the Japanese occupation era through images and words.

In traditional composition classes, the teacher would put a topic on the board and students would then do their best to write about it. At the Forest School, composition might begin with a discussion of how to describe the taste of a fig, because for primary school students, "it's easier to speak than to write." The students are asked to state their feelings into a tape recorder. Then the children are allowed to relax. In this way, even before they have begun to write, the kids have spent a part of class on relaxation, feeling, thinking about the subject, and comprehension. Then they get exposed to other things perhaps reading poetry by the Indian poet Tagore, or listening to a segment of Swan Lake-before they actually put pen to paper. The secret to composition at the Forest School is that "only through tranquility can one sense the world."

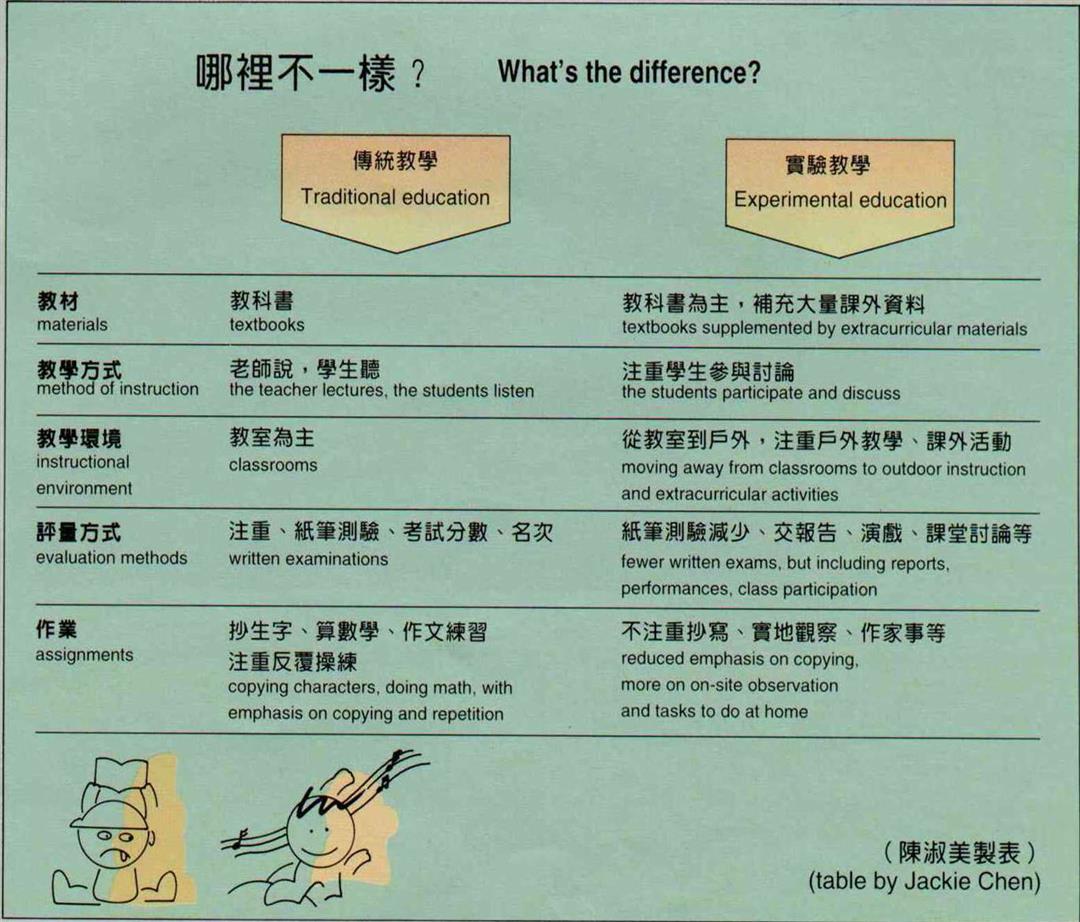

What's the difference?(table by Jackie Chen)

Student-centric

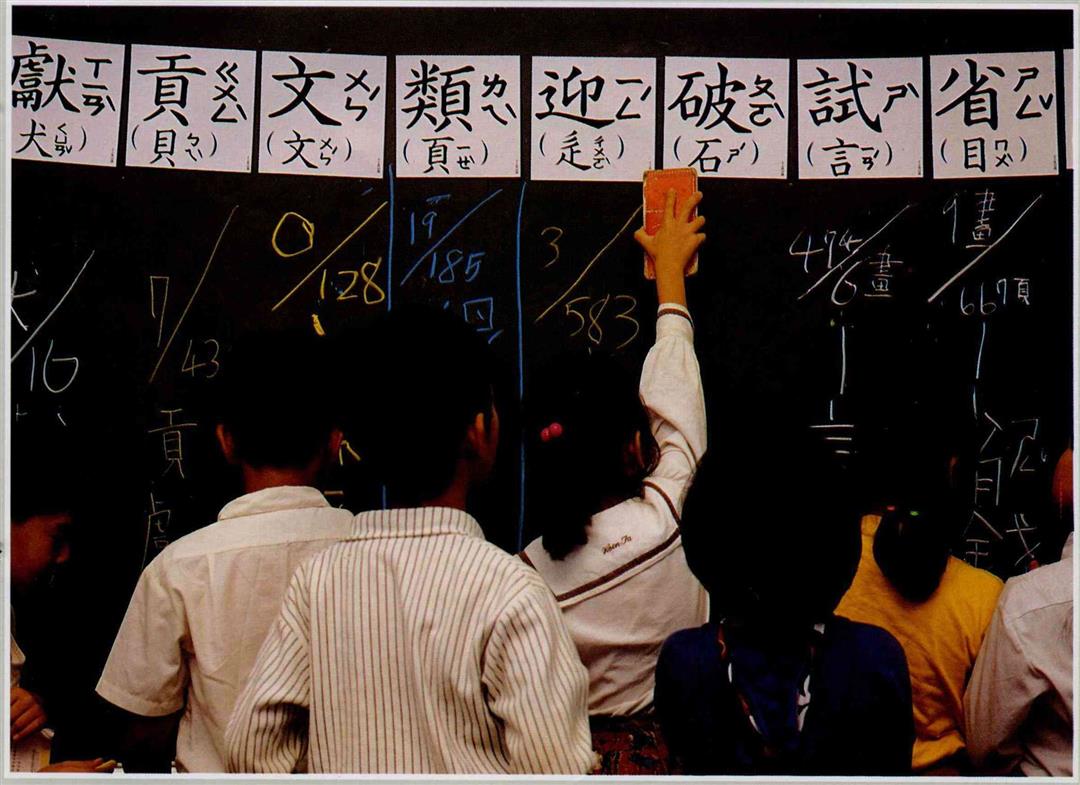

The spirit of reform is to allow children to participate in study and discussion. When you enter an experimental classroom, the vision before you is not one of meticulously arranged desks and chairs, but is a layout of separate areas for studying, playing, painting, and so on.

A few classrooms have even carved out a rest area using plastic dividers. If the children feel they have mastered something, they can go to this area to rest or read. They need no longer just stare at the teacher with a bored expression in their eyes.

"Basically the teacher is just a guide and a helper, but not an instructor," says Lin Pei-hsuan, a teacher at the Yu Min Primary School in Hsinchuang. In class, she often figuratively "comes out from behind the podium," so that the students can play the main roles in class.

For example, when the class got to the section on Liu Ming-chuan (a modernizing governor of Taiwan in the 1890s) in Chinese class, she didn't just go right to the text or begin practicing vocabulary. Rather, she started out with queries like "Who was Liu Ming-chuan?" "Why was he so far-sighted?" or "Why did he build the railroads?" The children are first brought into the discussion, which stimulates their motivation for learning. Afterwards the children can be gradually brought back to the main line of instruction in the standardized texts.

Lin Chiu-chin is a first grade teacher at the Wan Ta Primary School. She tries to use more lively methods to get her students to communicate every day. For example, she asks the children (who have not yet learned many Chinese characters) to write one sentence each day in their journals, using the Mandarin phonetic alphabet, on the subject "What I have to be thankful for." "This enables the children to stretch their imaginations even as they practice their phonetic symbols," she says. And the kids do not let her down: Each day they write inventive sentences such as "I am thankful for the bright sunlight that shines in my eyes," or "I am thankful for the warm air."

There is greater flexibility in the forward progress of the experimental classes. Teachers can design instructional activities to meet the needs of the curriculum. For example, in the Chinese language class on "Kung Jung Takes the Smallest Pear," the teacher got the kids to put on a little drama. For a third year lesson in the standardized texts on the aboriginal "Harvest Festival," the Tatun Primary School invited the Formosan Aboriginal Dance Troupe to perform traditional indigenous song and dance at the school.

It's no crime to emphasize grades; the only problem is that the system only emphasizes regurgitating memorized answers, not how to think.

Fun can be learning

At the Lung An Primary School, students in math class are encouraged to "learn by doing," which is to say to relate what they learn to daily life. One fifth grade student wrote the following in her class notebook: "Today the teacher taught us how to measure the length and width of our desks with a tape measure. My desk and Chang Hsiao-fang's desk were the longest in the class. Later in class I and Hsiao-fang and Lin Hsiao-yun measured our chest, waist, and head sizes. I was always several centimeters bigger than them, especially around the chest. My bust measurement is 78 centimeters. This year Hsiao-yun has already developed breasts, but my chest is still 10 centimeters bigger than hers. Am I too fat?"

To get the children interested in learning through playing is a major challenge for teachers in the experimental classes. Many teachers had been in the profession for many years, and they felt happy and confident in their work. But there was a lot of pressure when they took over the experimental classes. "I am thinking about teaching constantly, when I am eating, sleeping, showering," says Lin Chuan-hui of the "April 10" reform alliance. "The easy thing for a teacher to do is just hand the children the answers so they can spit them back. For someone like me, who comes out of traditional education, the first thing to learn is how to be patient and let the children think and discover for themselves. I can't get impatient and just give them the answer," explains Chiu Kuei-lan, a teacher at the Lung An Primary School.

In experimental classes, which focus on the experience of the student, the children are the core.

From indoors to outdoors

In order to respect the children, understand the children, and give each of them a learning experience appropriate to their needs, not only does the teacher need to open his or her mind, the place of study itself must be opened up. It can no longer be limited to the classroom.

Take for example the Chu Kuang Primary School, famous for its "open classrooms." They have turned the sand pits, grassy areas, pools, and pathways of the school's surroundings into educational exploration areas where students can play, measure the wind direction and temperature, understand the plant life, and search for insects. The goal is to allow the students to expand their learning territory, both physically and intellectually.

Taking classes outdoors is a big part of the changes. Wang Chun-yang, a teacher of natural science at the Hu Shan Primary School, takes advantage of the fact that the campus is located on Yangming Mountain, and virtually every week he takes the students out on a nature hike. He has often taken students even farther away, for example to see the Matsu Temple, the Memorial to the Anti-Japanese Resistance, the water fowl of the Pescadores, or the active volcano in Pingtung. "What does it mean to be a Taiwanese?" he asks. He often tells the students "if you don't know about things Taiwanese, or the natural environment of Taiwan, then you are not a Taiwanese."

Of course, many schools lack Hu Shan's geographic advantage, but they still do outdoor education. At the Chung Yang Primary School in Sanchung, teachers take the students out to see dikes, bridges, and water pumping stations, because these are special features of the landscape in the Sanchung area. In the experimental class at the Yu Min Primary School, the students felt very curious about the mountain they could see every day from the classroom windows, so the teacher made a special effort to design a special educational field trip to the mountains.

"Children are by nature curious and anxious to explore, so we do as much as we can to accommodate them," say Cheng Tuan-jung, principal of the Chu Kuang Primary School.

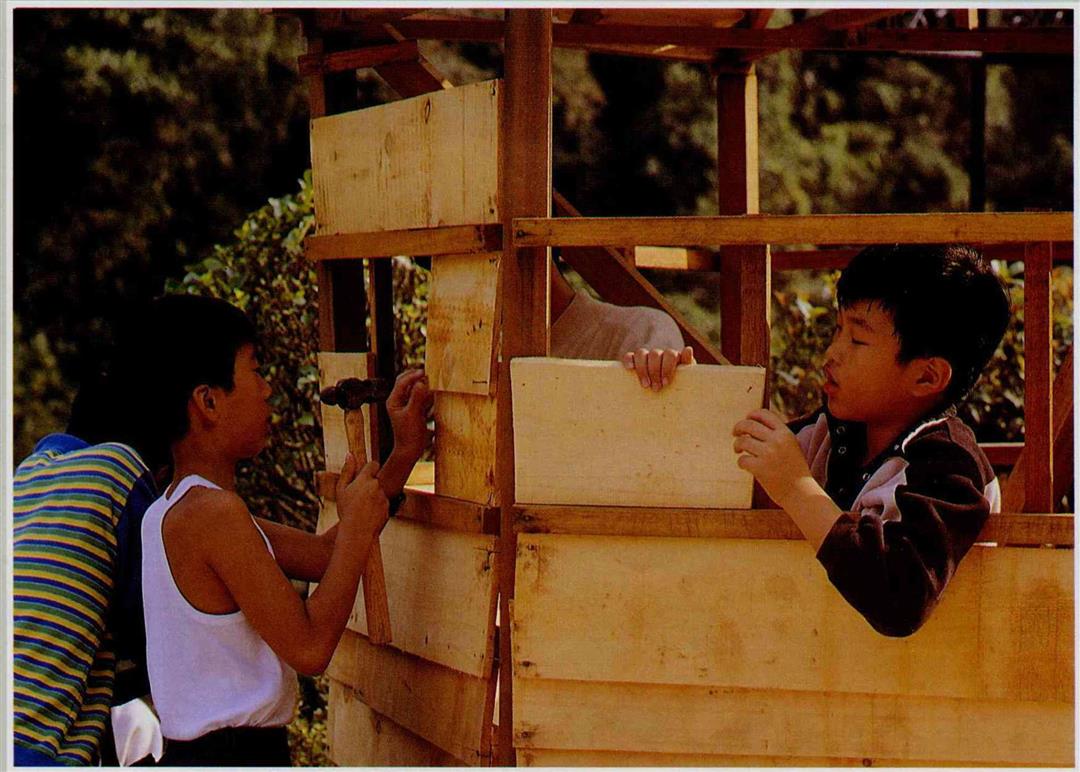

A child's learning is like building a house. After the foundation is firmly in place, you can build upward and outward.

Can't have too much fun

What's so novel about field trips? Most primary school classes only go about once or twice a semester, whereas the experimental classes go once or twice a month if possible. And at the Forest and Caterpillar academies, the students are exposed to the outdoors on a routine daily basis. In the morning they study "the keys to civilization," including Chinese language, natural sciences, and mathematics. After lunch comes the free period. The pupils can cook, build things, do art work, learn film appreciation, practice piano, take photos.... they join in whatever they like.

Here a teacher has taken his students outside with hammer and saw to knock together a small wooden treehouse, missing only a roof. With the sun shining down, some of the kids, under the supervision of a teacher, go to a nearby stream to explore, catch fish, and look at the rock formations. In the unbearable heat, some of the kids just strip down and play in the water to their hearts' content.

Grades are not everything

In these experimental classes, the teachers do not consider grades to be the main object. As for who gets to be class leader or arts section leader, teacher Lin Pei-hsuan lets the children vote under a rotational system so that everyone gets a chance. These roles are not just the monopoly of those with the best grades, as in normal classes. "We do this to build self-confidence in all the kids."

The evaluation methods are also very different. Traditional pedagogy emphasizes giving numerical or letter "outcome evaluations." But the experimental classes stress "process evaluations." The number of traditional pen and paper exams is cut back to two or three a semester, or even none at all.

"If there are grades, then there will be competition," says Lin Hui-chen, principal at the Lung An Primary School. Written exams are of course convenient and immediately allow the student to know whether he or she has mastered the subject matter. The negative side is that students only care about regurgitating the correct response, and not about the thought process. "At the primary school level, it is more important that the student understand how to think than have the answer," she says.

With fewer written exams, the scope of evaluation is broader. For example, assignments are no longer limited to repeated writing of vocabulary, math problems, or compositions. Instead teachers design novel assignments such as "estimate how many kilos of garbage there are in your house," "write about the flora and fauna in your neighborhood," "do housework," "draw up a classroom design of your own invention," "decide which math lesson you know best, and which you still understand the least"....

Teachers no longer assign grades based solely on tests. Keeping your desk clean, showing concern for others, outside assignments, reports, dramatic performances, or class participation all are weighed in assigning a grade.

"Sometimes a child will say to me, 'Teacher, I didn't realize you kept an eye on those things too," says Lin Pei-hsuan. The hard part for the teacher in this grading process is to avoid emotional choices and subjective feelings. "The children don't care as much about the grades as they do about whether or not the teacher is fair," she adds.

Parent-teacher cooperation

New forms of education place more emphasis on parent-teacher cooperation than traditional forms do. Parents are encouraged to come to the school to see how the teacher performs, to make classroom props, or to accompany the class on field trips. There are parent-teacher meetings virtually every month, and frequent contacts between the two sides.

At the Lung An Primary School, students wanted to know how cream was made. One parent stepped forward to arrange a tour of the dairy factory where he worked. In another case, when the aboriginal dance company-which normally gets tens of thousands of NT dollars per show-performed at the Tatun School, they did so for free through the friendly mediation of a parent. And there are many parents who go to the school early in the morning to tell stories to the children....

Of course some parents don't agree with the overall scheme, and remain skeptical of these experiments. "Since when does playing all day count as learning?" wonders one adult. And teacher Lin Chiu-chin adds that whenever instructors give an untraditional assignment, parents think they are just playing games. One parent even charges that some parts of experimental education are just "excuses for lazy teachers. The teachers just let the kids play and don't have to do anything themselves."

As far as education experts are concerned, some of these concerns are too extreme. Hsu Hui-ming, a specialist in preschool education, says that children are in the "sensory stage" until about age six. Everything they learn is through stimulation of sight, hearing, touch, and so on. Beginning at age seven they can accept a bit of intellectual learning, but still the main sources of learning are through the stimulation they get from observing the environment, doing things themselves, and playing. "The important thing is that their environment be rich in resources, and that the teacher be adequately active," she suggests. Relatively open teaching methods definitely are more effective in this respect than traditional compulsory rote memorization.

There is still a long way to go for both parents and teachers on the road of experimental education. But there has been a start, the issues have been raised, and discussion is underway. Will these experiments be able to follow the road increasingly nearer to their ideal destination? Anyway, it will be a learning experience for all of us.

[Picture Caption]

p.19

(courtesy of the National Institute of Translation and Compilation)

p.20

The sun is shining, the stream water glistens. The older children join the younger, presenting a lovely picture of life at the Caterpillar School.

p.21

What's the difference?

(table by Jackie Chen)

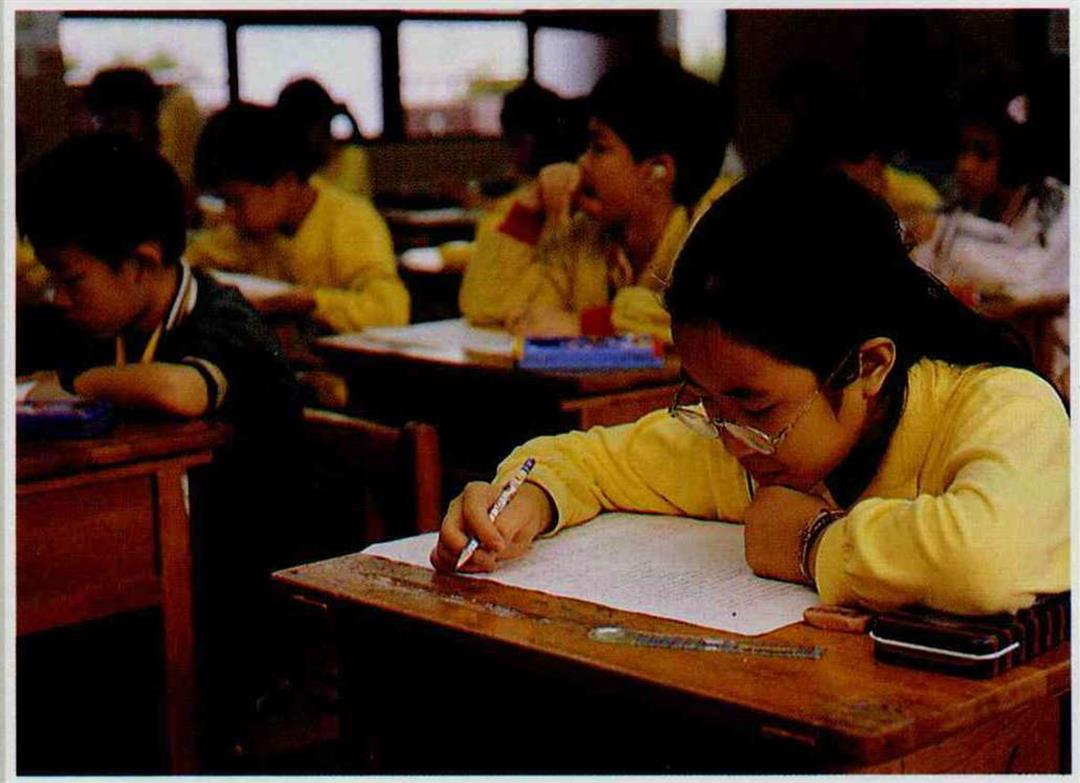

p.22

It's no crime to emphasize grades; the only problem is that the system only emphasizes regurgitating memorized answers, not how to think.

p.23

In experimental classes, which focus on the experience of the student, the children are the core.

p.24

A child's learning is like building a house. After the foundation is firmly in place, you can build upward and outward.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)