Longing For Spring--Old People in the Earthquake Zone

Chang Chiung-fang / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Robert Taylor

May 2000

Six months have passed since last year's 21 September earthquake. Since the disaster, the young and middle-aged have been busy with reconstruction, and children have gradually been able to return to school. But many old folk are still in a state of shock, and are facing the massive changes in their lives with a sense of powerlessness and bewilderment.

After Japan's Kobe earthquake, there were a number of cases of old people dying alone and unnoticed in the prefabricated houses where they were accommodated.

Taking the Japanese experience as a warning, how can we prevent the same problems occurring in the quake zone in Taiwan? What situation are seniors there in today? And which organizations and individuals are caring for these old people?

Six months have gone by since Taiwan's devastating earthquake of 21 September 1999. But there are still a number of old people living in tents beside the perimeter wall of Puli Elementary School.

Mrs. Chiu Pan Chiu-chu is 89. She lost touch with her son many years ago; her daughter, who lives in Taichung, offered to take her in after the quake, but she was unwilling to go. Community workers wanted to arrange a prefabricated home for her, but she refused, insisting instead on living in a tent across the road from the ruins of her former rented apartment.

"I'm used to living here. I know all the neighbors. If I can't find a place to rent nearby, I'd rather live in a tent," says Mrs. Chiu. "There's a dewdrop on every blade of grass [i.e. Heaven provides for all]-if I have to survive by eating grass then I'm happy to."

Things do not look good either for those seniors who were put into residential care after the earthquake wrecked their homes. In Taichung County and City, seven old people's homes which are members of the Unity Nursing League allocated beds to old people from the earthquake zone. League general secretary Liao Wen-yi says that after going into the homes, some seniors showed a decline in their physical and mental functions, becoming incontinent, forgetting the names and phone numbers of family members, or even pulling the stuffing out of their pillows and scattering it on the floor.

"Most of the old folk still haven't got over the terror of the quake. They can't sleep at night without the light on, and they only feel safe if somebody is with them," says Liao. He says the league initially took in over 80 old people, but because they couldn't adjust to living there, some went into prefabs, and some went to live with their children once the latter could take care of them again. Today, only a dozen or so are still in the homes.

Though both old people and children are dependent on others, the two groups are valued very differently.

Scant concern for the elderly

The quake destroyed many people's homes, but it also broke up long-established neighborhood relationships and community care and support mechanisms. Wu Yu-chin, general secretary of the League of Welfare Improvement for Older People, states that even before the quake, the stricken areas in central Taiwan lacked organized welfare services. But after the disaster, even those informal community support networks which had existed broke down. With many invalids, orphans and old people in need of care because of the quake, the area's originally insufficient social welfare resources were shown to be pitifully inadequate.

According to government statistics, the earthquake left 384 old people in central Taiwan with nobody to look after them due to the death of family members; it also orphaned 125 children.

However, although both young and old were left alone and without means of support, things have gone very differently for the old folk than for the orphaned children.

Huang Cheng-hsiung, executive director of World Vision Taiwan, says that people fell over themselves to take in the orphans created by the earthquake, but the elderly got scant help. The main reason is that children who lost both parents received NT$2 million in death benefit, whereas most old people whose children died received no benefit since their children were already married. Naturally the elderly were not "worth" as much as the orphans.

Twenty-plus "community family support centers" have been set up by private-sector organizations in various townships of Nantou County, with funding from the county government. These do provide some services to old people, but they mainly focus on looking after low-income families and children. Only Bo-Tree Evergreen Village, set up in Puli without government help by the Buddha Incense Academy, has made it its mission to care for unsupported seniors.

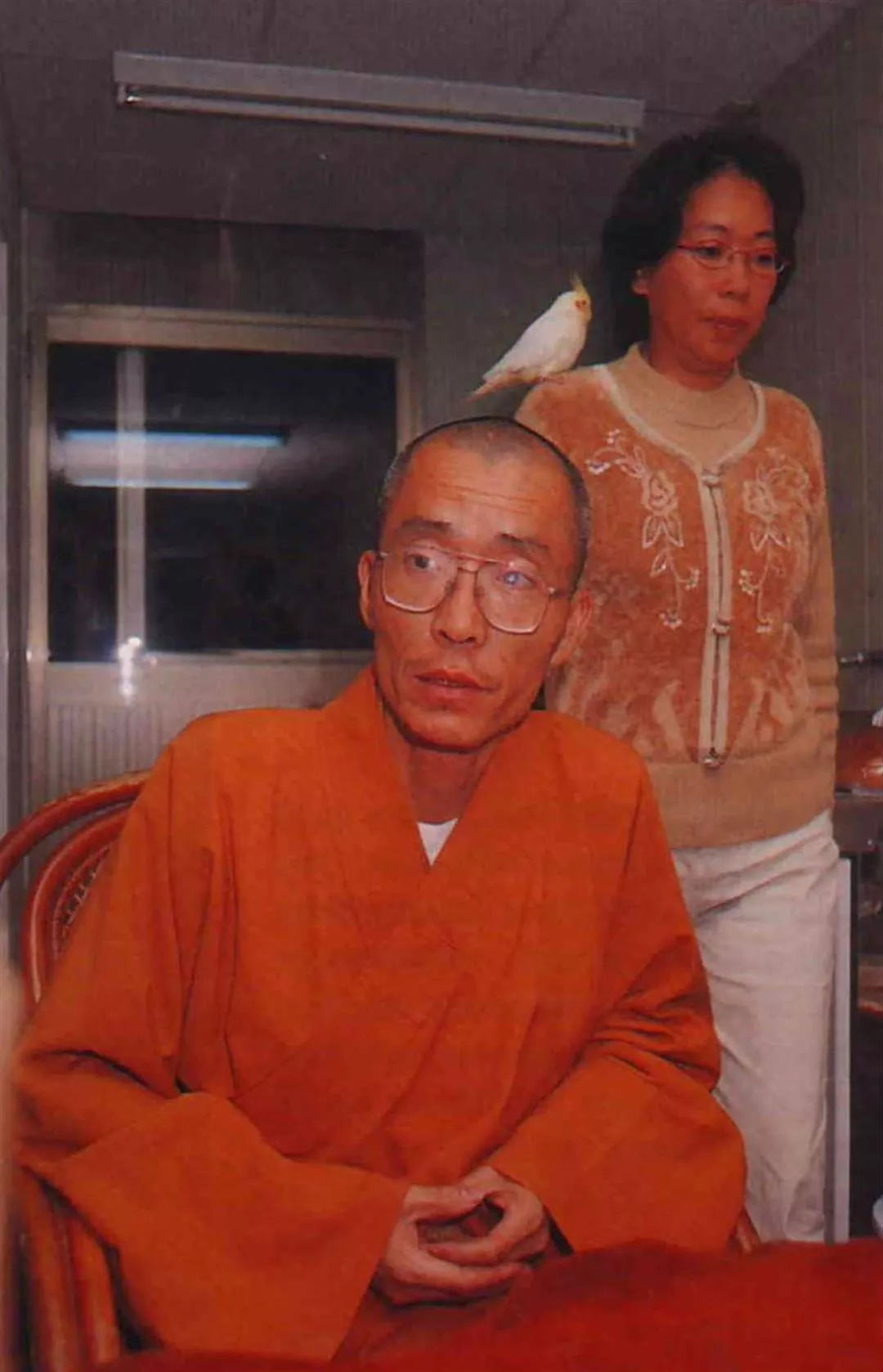

The Academy's executive director, Buddhist Master Titung, says that after the earthquake he discovered that many people were taking care of children, but nobody was looking after the elderly. "If things go on in this way, family bonds will unravel," says Master Titung. Hence he decided to devote himself to caring for seniors in the disaster area, setting up Bo-Tree Evergreen Village to take in old people with no-one to care for them. "I aim to set an example to families, in the hope that this will influence society for the better."

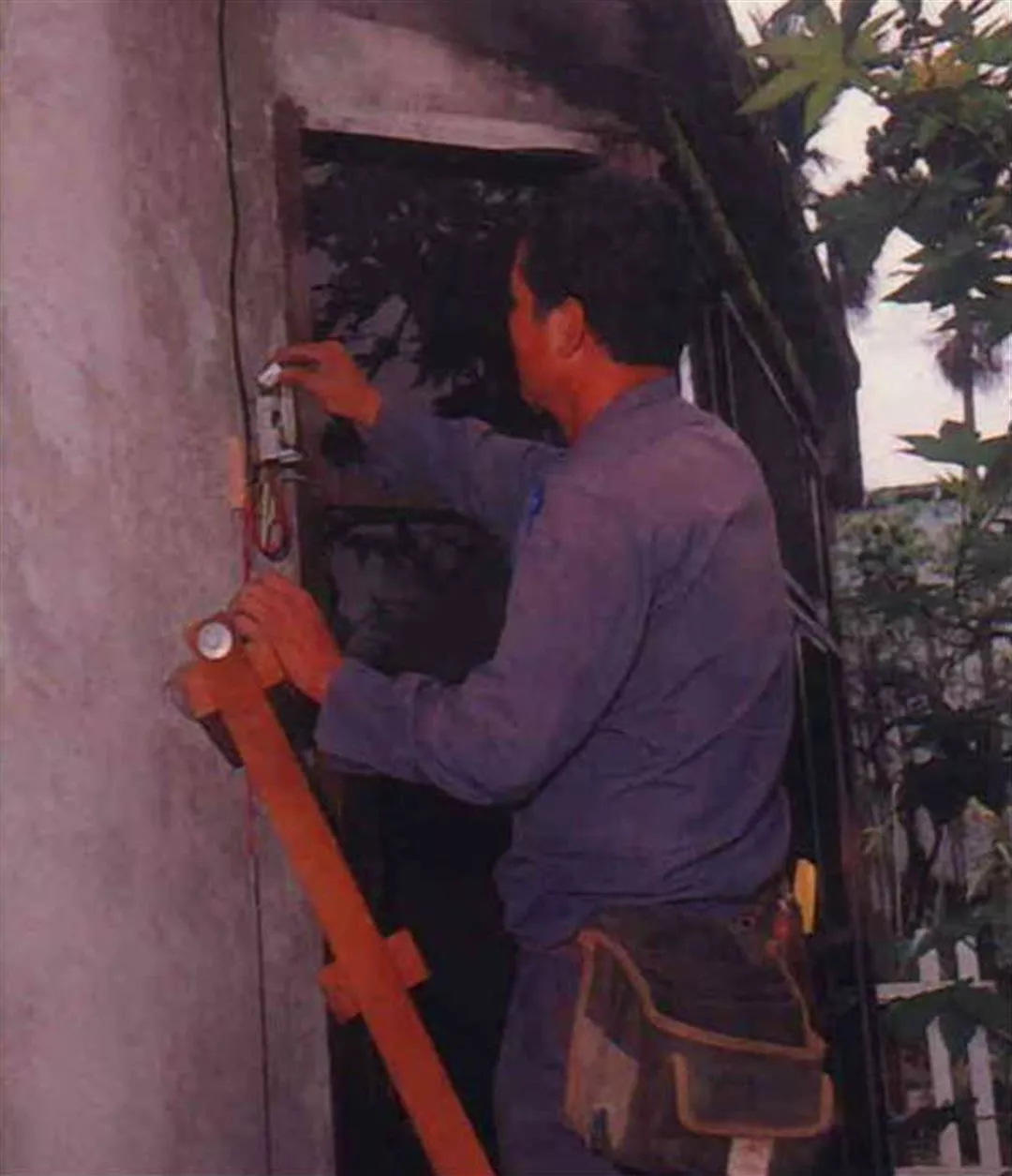

Another organization which has involved itself in support work in the quake zone is World Vision Taiwan. It set up a station in badly hit Puli, where as well as taking care of children and families, it also began to look for ways to help old people. In some of the areas worst affected by the quake-Puli in Nantou County, and Hsinshe and Takeng in Taichung County-World Vision Taiwan pays benefits to unsupported seniors, and is installing emergency alert systems for them. It also plans to distribute food to old people, and help with their travel expenses when they seek medical care.

After their rented houses collapsed, a number of old people took shelter in tents next to Puli Elementary School, where they have remained for more than six months. Eating, washing and sanitation all pose difficulties, and the old folk all have persistent coughs from being constantly exposed to the elements.

Won't you take me back home?

When community workers entered the disaster area, after attending to the immediate problem of finding accommodation for old people, they had to get a clear picture of the many difficulties facing seniors.

"After the quake, whole communities were split up," says Lin Yi-ying, executive secretary of the Old Five Old Foundation, which is doing neighborhood reconstruction work in Puli. Lin says that in Puli, those seniors who survived the quake ended up scattered far and wide: some were put into old people's homes, some went away to stay with their children, some went into prefabs, and some stayed on locally, living alone.

"Won't you take me back home?"-this is how one old lady pleaded with Associate Professor Wu Shu-chung of National Taiwan University's Institute of Health Policy and Management when she visited an old people's home, although the home was of excellent quality. "Old people's love of home and family should be respected," comments Wu, who says that the systems to allow people to grow old within the community should have been set up long ago, and this applies in the disaster areas too.

Attachment to home is a common psychological trait among the elderly, and one that has caused major problems for old people's homes in the aftermath of the 21 September earthquake. Wu Hua-chien, a community worker with the Old Five Old Foundation, says that many elderly quake victims insisted on staying in their own neighborhoods, because firstly they had more privacy there, secondly they were afraid that if they went into a home people would speak badly of their children, and thirdly they would miss their long-established neighborly relationships. For these seniors, being cared for in the community is the only feasible option.

Sixty-eight-year-old Lin Sheng-wang, who is both a stroke victim and a diabetes sufferer, has lived alone in a rented house in Puli's Wukung neighborhood for many years. The earthquake damaged the house's tile roof, causing it to leak until the landlord covered it with a simple tarpaulin.

Sitting alone in his doorway, Lin appears somewhat desolate. Since his stroke he has been unable to work, so he relies entirely upon his disability benefit and meager pension. "I spend every penny that comes in," he says. Though he has poor mobility, he still prepares his own meals, cooking once in two days.

Recently, World Vision Taiwan and the Old Five Old Foundation installed an emergency alert system for him. If he falls ill, he need only press the button on his wrist, and the response center will take action immediately. The center also phones regularly to check that he is all right. Lin says: "It's a wonderful service! They ring up every three days-that's more often than my relatives!"

Old Mrs. Wu, another stroke victim, also lives alone. Her house itself is in a reasonable condition, but inside it is dirty and disordered. After the earthquake, when supplies were short in the disaster zone, the old lady could only stand and watch as strangers carried off her bed and took away her aluminum doors and windows. As well as her granddaughter, who though married herself comes to look in on her and do some cleaning when she can, community workers from the Old Five Old Foundation also make visits, and have installed an emergency alert system. When asked why she didn't choose to go into a prefab or an old people's home, Mrs. Wu replies: "I can't do that. The spirits won't let me go-I have to stay here to venerate them!"

Mr. and Mrs. Pan's kitchen and bathroom collapsed in the quake, so a charity group gave them a tent to use as a makeshift bathroom. It is enough to assure a measure of privacy, but not to keep out the cold wind.

East, West, home's best

To be able to stay and rebuild their homes on their original spot is these old people's greatest wish. Even if they can only put up a structure a few square meters in area, with walls and roof made of sheet metal panels, the prospect fills their hearts with hope.

Huang Hua-mei, who lives in Puli's Tanan neighborhood, is in her eighties. Forty years ago, hers was one of nine households rehoused here by the Rotary Club after their homes were swept away by the 7 August floods of 1959. Last September's earthquake destroyed their homes again. For the time being, she and some neighbors are living in a temporary shelter on nearby farmland they have rented, while they wait for their houses to be rebuilt. The recent persistent heavy rains have made the ground inside the shelter constantly wet, and these seniors all hope desperately that their houses can be rebuilt soon.

"We old folk don't mind if we live in a sheet metal house-as long as it keeps the wind and rain out and doesn't fall down if there's an earthquake, that's plenty good enough!" Huang Hua-mei doesn't ask for much.

At present, the main priority for the 21 September Quake Zone Home Rebuilding Team-a private-sector relief organization set up after the quake-is to build houses for old people living alone, low income households and the disabled. Team leader Wang Ching-feng says: "The government subsidy of NT$200,000 for each collapsed home isn't enough to build a house, and the prefabs are only a temporary arrangement. When the time limit for dismantling them comes, what will people do then?" It is necessary to find proper, long-term solutions to the problems of people in the disaster area, Wang says. Those whom the Rebuilding Team assesses as being eligible for its assistance only have to put up reconstruction fees of NT$10,000 per ping (3.3 square meters), for which they can use the government subsidy. The rest comes from funds raised by the team. "Giving them a permanent home is the starting point of all reconstruction," says Wang.

Fengchiu Village in Hsinyi Rural Township has 78 households, counting some 430 souls. Chuan Hsin-chun (far right), the village's church elder, takes community workers from the Old Five Old Foundation and World Vision Taiwan to visit the villagers most in need of help.

Looking for the silver lining

Rebuilding is naturally the best choice, but for many people it is not an option, for instance if they have no land of their own. They can only temporarily move into prefabs or homes made from freight containers. But many seniors refuse to leave their old homes.

"Changes in their environment make old people feel very insecure," says Wu Yu-ching. No-one should deprive the elderly of the right to make their own decisions, she says, but apart from affording this respect, the main thing is to get them to accept the services which are available to them.

"After it started raining, the demands of old people in the disaster area changed," says Lin Yi-ying. While the weather was dry, they still wanted to stay in the tents no matter how cold it got. But once the rain made the ground wet underfoot they could no longer bear it, and many phoned to ask: "Is that prefab you told us about still available?"

Lin smiles as she explains that although the heavy rain added greatly to the misery of people in the quake zone, as the last straw which finally made many seniors willing to go into prefabs it gave her a good excuse to urge them to leave their old homes behind.

Bo-Tree Evergreen Village, accommodated in prefabs in Puli's Yencheng district, provides free food and accommodation to seniors with no-one to care for them. The home's only demand is that residents' relatives should visit them regularly.

Bo-Tree Evergreen Village

The number of prefabricated homes is limited, and not every old person is eligible for one. At the same time, to live in a prefab one has to be able to look after oneself. Another option open to old people who are willing to leave their old homes is Bo-Tree Evergreen Village. Any senior whose home was damaged or destroyed by the quake, whose children are too busy with reconstruction to be able to look after them properly, or who has no-one to care for them at all, is eligible to stay at Bo-Tree Evergreen Village.

At the beginning Bo-Tree simply bought a new bed for each new arrival. But as more and more people got to know of its existence, various agencies began referring seniors in need of care, and over the past six months it has successively cared for more than 280 old people. Some have returned home after their houses have been rebuilt, and some have gone to live with their children, but today over 70 seniors are still living at Bo-Tree.

In February this year, Bo-Tree Evergreen Village moved out of its original accommodation-vacant units in an apartment building made available after the quake by a construction company-and moved into prefabricated units in Puli's Yencheng neighborhood donated by the YWCA and the Bank of Overseas Chinese.

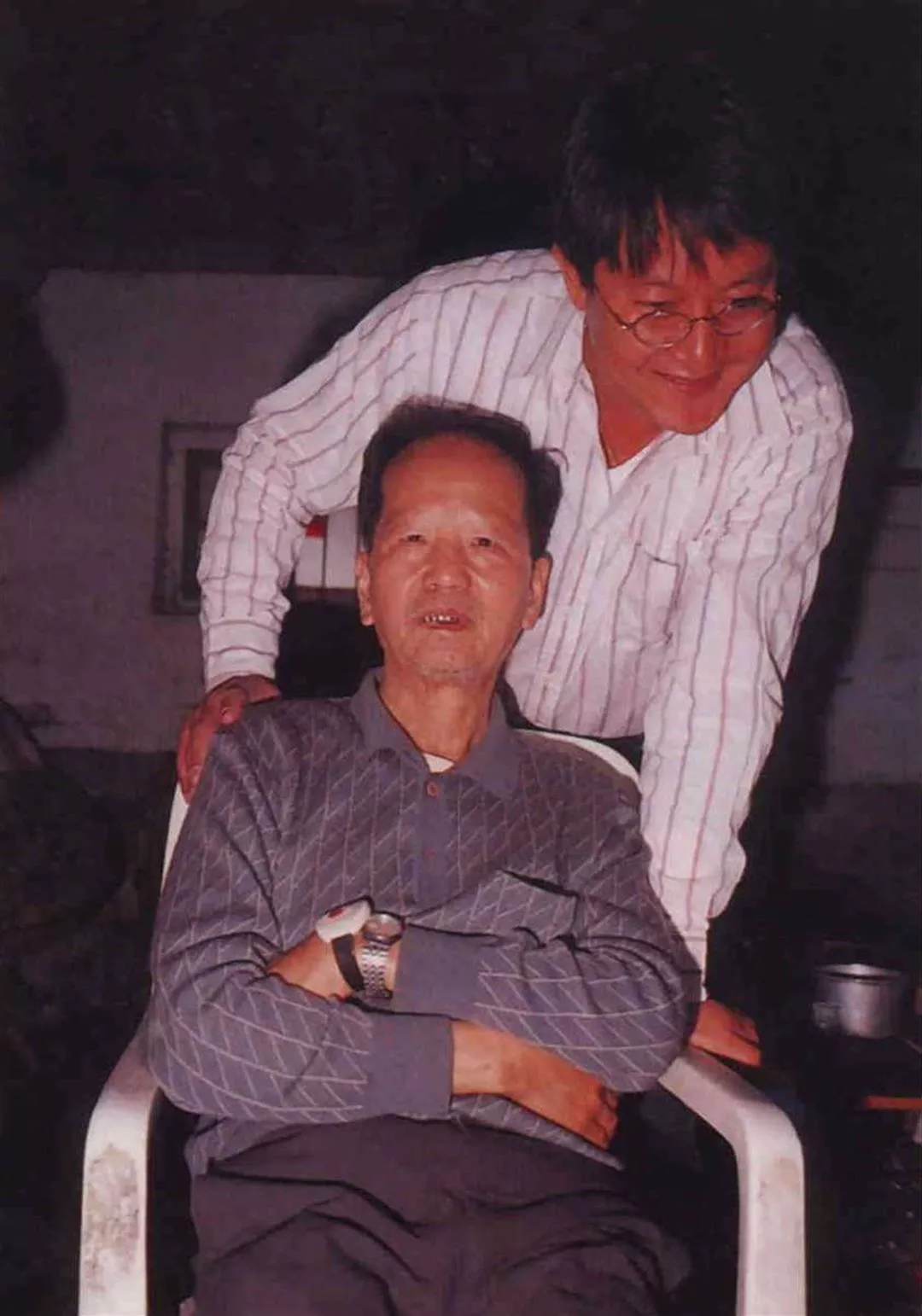

The seniors at Bo-Tree each have their own unique experiences and their individuality.

One 85-year-old Hakka woman lost her husband and all her children in the quake. But she is still optimistic and bears no grudge against Heaven or man.

As for one old couple, the old lady is not very mobile due to a stroke, while her husband's mind is not very clear. But the two take good care of each other, with the old lady giving her husband directions as to what to do, and they work quite well together.

But there are also many old people who have been unable to adapt. One old lady of 96 would huddle up under her quilt and weep every night after coming to Bo-Tree. When the staff asked her what she was so upset about, she replied: "My house has fallen down, I'm homeless!"

One old man, a mainlander, did not speak at all when he first came to Bo-Tree. Only later did staff gradually learn that he owned a stationery shop. During the earthquake he ran out of the building, but later he went in to fetch some things. While he was inside there was an aftershock, and he fell to the ground and sat there shaking with fear. In the end he didn't bring out anything. "My US dollars and gold are all buried under there!" he says.

Seeing the needs of old people in the earthquake zone, Buddhist Master Titung and Bo-Tree Evergreen Village director Chen Fang-tsu have devoted themselves to the task of caring for them. Although they have no reliable source of funding, they believe their desire to do good will bring good fortune, and people will surely come forward to help them continue their work.

A forgotten group

Tsai Mei-hsiu has been a caregiver at Bo-Tree Evergreen Village since October last year. She says: "Many old people couldn't sleep at night when they first came here, and when there were aftershocks they were terrified. It was heartbreaking to see them!"

Widespread lack of concern is another big problem. Wu Hua-chuan comments: "The old people in the quake zone seem to have been forgotten about. They have no will to live, and are just waiting to die."

Dr. Lin Pen-tang of the psychiatry department at Taichung Veterans General Hospital visits Bo-Tree Evergreen Village weekly. As well as taking residents' blood pressure and checking their physical condition, he also chats with them to relieve their psychological stress. "At the beginning the old folk showed psychological reactions such as loneliness, dejection, homesickness and insomnia. But after a while they raised each other's spirits, and things have got much better," says Dr. Lin.

"After you've seen a number of cases you can't help but worry," laments Wu Hua-chuan, who has been a community worker for the Old Five Old Foundation for only three months. "If an old person is able to look after themself that's pretty good, but I've seen many who also have to take care of younger people, such as their mentally handicapped children."

For instance, Mr. and Mrs. Pan Yen of Tanan neighborhood live with their divorced daughter and her son. The old couple are both in their 80s, yet they not only have to look after themselves, but also have to take care of their daughter and grandson, who had nowhere else to go after the failure of the daughter's marriage. The earthquake destroyed part of their house, so they put up temporary shelters to use as a kitchen and bathroom, and are just living from day to day.

One old aboriginal lady in Nantou's Hsinyi Rural Township has lost her son, and her daughter-in-law is bedridden due to a stroke. The old lady not only has to take care of her daughter-in-law but also her grandson, and she is struggling to cope.

Even just cooking three meals a day is a challenge for many old people. Wu Hua-chuan says that good nutrition is very important for the elderly, but because cooking is too burdensome, many seniors do not eat healthily, and their food is often not fresh. Some cook once and then eat for several days, some boil rice and vegetables together in the same pan, and some eat instant noodles every day. To address this problem, the Old Five Old Foundation is looking at setting up a communal kitchen in Puli's Tanan neighborhood, to make meals less of a chore for the old people there.

The League of Welfare Improvement for Older People has set up a "neighborhood family support center" in Nantou's Chushan Township to train staff to provide services such as home visits, telephone wellbeing checks, home care, and meals on wheels. Wu Yu-chin says: "In the past, neighborhood relationships were ones of selfless giving, but now we hope that by covering the expense of home care and meals-on-wheels services, we can put them on a more permanent footing."

For residents at Bo-Tree Evergreen Village, cooking is not a worry: the seniors living there pay nothing for their food or accommodation, and the foundation provides three generous meals a day of vegetarian food which is both nourishing and hygienically prepared. But how will Bo-Tree carry on when the time comes for the prefabs to be dismantled? And where will the old people go?

Master Titung explains that Bo-Tree Evergreen Village was set up under the one-year shelter program for earthquake victims. But care for the elderly is not something that can be suddenly suspended, so he is thinking about plans for how to carry on once the first year is up, such as setting up a day care center or a seniors' leisure farm. At present Bo-Tree's costs are entirely covered by Master Titung's income from performing Buddhist rites, and from charitable donations.

The Old Five Old Foundation and World Vision Taiwan are currently installing emergency alert systems for old people living alone. A senior need only press a button worn on the wrist to contact the staff at the response center.

Help all the aged

Though the problems of old people in the earthquake zone are more concentrated and more pressing than in other areas, they reflect old people's issues in Taiwan at large.

At a National Seniors' Summit held in January 2000 by the Ministry of the Interior, delegates from the quake zone said that a majority of the activity centers there had been destroyed by the tremor, leaving the elderly with few places to go for leisure activities. Thus they could only sit at home and do nothing, and lacked opportunities for social participation. League of Welfare Improvement for Older People general secretary Wu Yu-chien says that encouraging social participation is the best way to prevent old people "dying of loneliness," so the opinions of the quake zone delegates should be taken very seriously.

Because the quake left government administrative systems in chaos, the provision of resources to the elderly was disrupted, and in many areas old people have not received their pension payments for several months. The majority of old people are completely unaware of the channels and procedures for applying for assistance. Wu Yu-chin says that apart from the interruption in pensions, many other services for the elderly are also being squeezed due to a shortage of funds. For instance, home care visits have been cut from 25 hours to 16 hours a month, and the frequency of meals on wheels has been reduced. This situation undoubtedly adds to the difficulties of old people in the disaster area.

Perhaps seniors in Taiwan are more resilient, or perhaps they are just more accepting of their fate. Wu Yu-chin says that at present the situation for old people in the earthquake zone is not particularly acute. But after only six months, some problems may not yet have come to the surface-it is still too early to pass judgement. For instance: after two years, when the prefabs have to be dismantled, where will the seniors living in them go? After four years, when the various social welfare and charitable organizations shut down their operations in the quake area, will the local authorities be geared up to take over the work of caring for the elderly? These are all difficult issues which the government will have to face.

In early May, at the height of spring, life is bustling and burgeoning in both the human and the natural world. Yet in the earthquake zone, old people are still living dejectedly from day to day. One cannot help but wonder when this coldest winter in their lives will give way to spring.

Old Mr. Lin, who lives in Puli's Wukung neighborhood, says enthusiastically: "It's a wonderful service-they're better than family.".

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)