Shihchinyu Sanfang:Lukang's Legendary Incense Firm Lives On

Kaya Huang / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

July 2008

Some 400 years ago in the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties, Han Chinese immigrants to Taiwan brought with them burgeoning trade and commerce, as well as the exquisite arts of the provinces from which they hailed: Fujian and Guangdong. Many immigrants from Quanzhou, Fujian settled in Lukang, where some earned a living as artisans. Honing their skills there, "Lukang's master craftsmen" grew renowned for their pewterware, lanterns, woodcarvings, paper cuttings for windows, and incense. All of these items can still be found there in abundance.

For Chinese, incense is intimately connected to matters of faith, and it is easy to find incense shops that have been established for 100 years or more in Taiwan's historical towns. Located across from the parking lot of Lukang's Tienhou (Mazu) Temple, the Shihchinyu Sanfang incense shop is Taiwan's oldest. Established by Shih Fa, an immigrant from Quanzhou, it has been in the same family for seven generations. The current boss, Shih Chi-hsun, has a son, Shih Yeh-chih, who is preparing to take over. So the younger Shih will make it eight generations. The stories that have been passed down from one generation to the next in this legendary establishment are legion, but challenges remain.

Lukang residents aren't strangers to Shihchinyu Sanfang, which was established in 1756, 252 years ago. It stands out among incense shops for holding to the formulas passed down from the proprietors' ancestors and for continuing to make their incense by hand. The shop's adherence to tradition and its location in close proximity to Lukang's City God, Tienhou, Hsintzu and Three Mountain Kings Temples, where the incense smoke never stops swirling, has helped to create the century-old legend of

"Lukang incense."

This story begins with the very origins of incense itself. Shih Chih-hsun, the store's seventh-generation proprietor, notes that legend has it that the burning of incense dates to the lifetime of Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism. When it was hot and stuffy, devotees listening to his sermons found themselves becoming drowsy, and their body odor detracted from the ceremonial decorum. Consequently, believers were suddenly inspired to get some fragrant wood, cut it into small strips and place them in receptacles to burn. The aroma both kept people from dozing off and also masked the stink.

That's the way Indian legend tells it, but Chinese historical documents take a different tack. According to The Book of Documents, China's oldest historical work: "With fragrant incense, one senses the presence of the spirit." In ancient times, two or three millennia ago, the Chinese would "light incense to call forth the presence of the spirits." During worship, alcohol and meat weren't indispensable offerings, but incense was. But the "incense"-or xiang-that was burned during libation ceremonies in the era before the Qin and Han dynasties was quite unlike today's ceremonial incense. Rather, it referred to herbs, orchid petals and spices. It wasn't until the rule of the Wu emperor (265-316) during the Jin dynasty, when vassal states would pay tribute to the Chinese court with "exotic herbs," that xiang began to be worn or burned to ward off evil and illness, or used in herbal prescriptions to promote good health.

Making incense is both physically taxing and dependent on the weather. Thanks to a sense of cultural mission, the tradition of making incense has survived through two centuries. The photo on the facing page shows Shih Yeh-chih (right), the eighth generation in his family to work in Shihchinyu Sanfang. He is preparing to take over the business so as to keep traditions of incense making alive.

The mysteries of agarwood

"Based on use, appearance, color and aroma, incense can be split into several groups, including incense sticks, horizontal incense sticks, incense coils, incense towers and incense beads. Then there are modern versions of incense, such as five-color incense, perfumed incense and menthol incense. The most widely used are incense sticks. Because these long upright sticks resemble pillars, they are also known as in Chinese as "incense pillars," explains Shih Chi-hsun, who learned traditional incense-making techniques from his father Shih Yi-han.

As for the actual "sticks" in "incense sticks," they are known as "incense legs." Made from bamboo, they come in a range of thicknesses, from 0.1 centimeters to 2-3 cm, and are typically 24-36 cm long. But Shihchinyu has manufactured incense sticks as thick as a telephone pole that an adult would need both arms to encircle. In August of 2004, for the fire-dragon ceremony that is part of the Mid-Autumn Festival at Lukang's Huan Temple, Shih Chi-hsun and master incense maker Tung Pao-lung spent a month and a half creating a stick that was four meters long, weighed about 120 kilograms and could burn for half a month.

"The incense we sell in our store is mostly made from agarwood and sandalwood," says Shih Chi-hsun. He explains that unlike sandalwood incense, which is made from a naturally fragrant wood, agarwood isn't simply the wood of a certain kind of tree. Rather, agarwood is taken from the heartwood of Aquilaria trees after they produce a resin in response to an infection of mold. By itself, the wood is quite soft and lacks any special fragrance. Research has shown that various species of Aquilaria (family Thymelaeaceae) can produce agarwood, including several varieties native to Malaysia, India and mainland China. Taiwan doesn't produce any agarwood and relies on imports from Vietnam and Cambodia.

Agarwood is extremely valuable. This piece is worth about as much as an SUV.

The more resin, the better

"Generally speaking, the denser the agarwood, the more resin in it and the higher the quality," says Shih Chi-hsun, as he places a pure piece of jet-black agarwood, passed down from his ancestors, into water. "Consequently, in olden times agarwood was given one of three grades depending on how far it sank." If it sank to the bottom, it would be classed as "sink-in-water incense" (the highest grade). If it partially sank and partially floated, it would be given the next grade down: zhan incense. The lowest grade of agarwood incense, which bobbed near the surface of the water, was known as huangshou (yellow-ripened) incense.

Usually, the darker the color and the denser the material, the higher the quality of the agarwood. But Shih Chi-hsun explains that cause and effect with agarwood is complicated, and the quality of the wood can vary depending not only on the amount of resin in it, but also the age of the resin and whether the tree it came from was alive or dead. Hence, one can't simply make a judgment based on appearance and physical properties. "It's still best to light it and let your nose make the call!"

For incense collectors, the attractions of incense are like those of the fine arts.

"Even among trees of the same species, not every tree will produce agarwood," says Shih Chi-hsun's wife Hung Pao-chen. "Tree placement provides no guarantees. Sometimes, differences in trees' exposure to the sun can result in different kinds of aromas. If there is ample sun, the resulting resin is richer and thicker, and the aroma of the incense will be more concentrated." She explains that the unreliable nature of agarwood formation coupled with the high demand in recent years has pushed a number of agarwood-producing tree species to the brink of extinction. And the price of agarwood has been rising higher and higher.

"When I went to Vietnam 20-odd years ago to buy agarwood, a kilogram cost US$25,000. At that time the exchange rate was 1:40, so it equaled NT$1 million. Now there is simply no top grade Hoi An agarwood on the market, no matter what price you want to pay!" sighs Shih Chi-hsun.

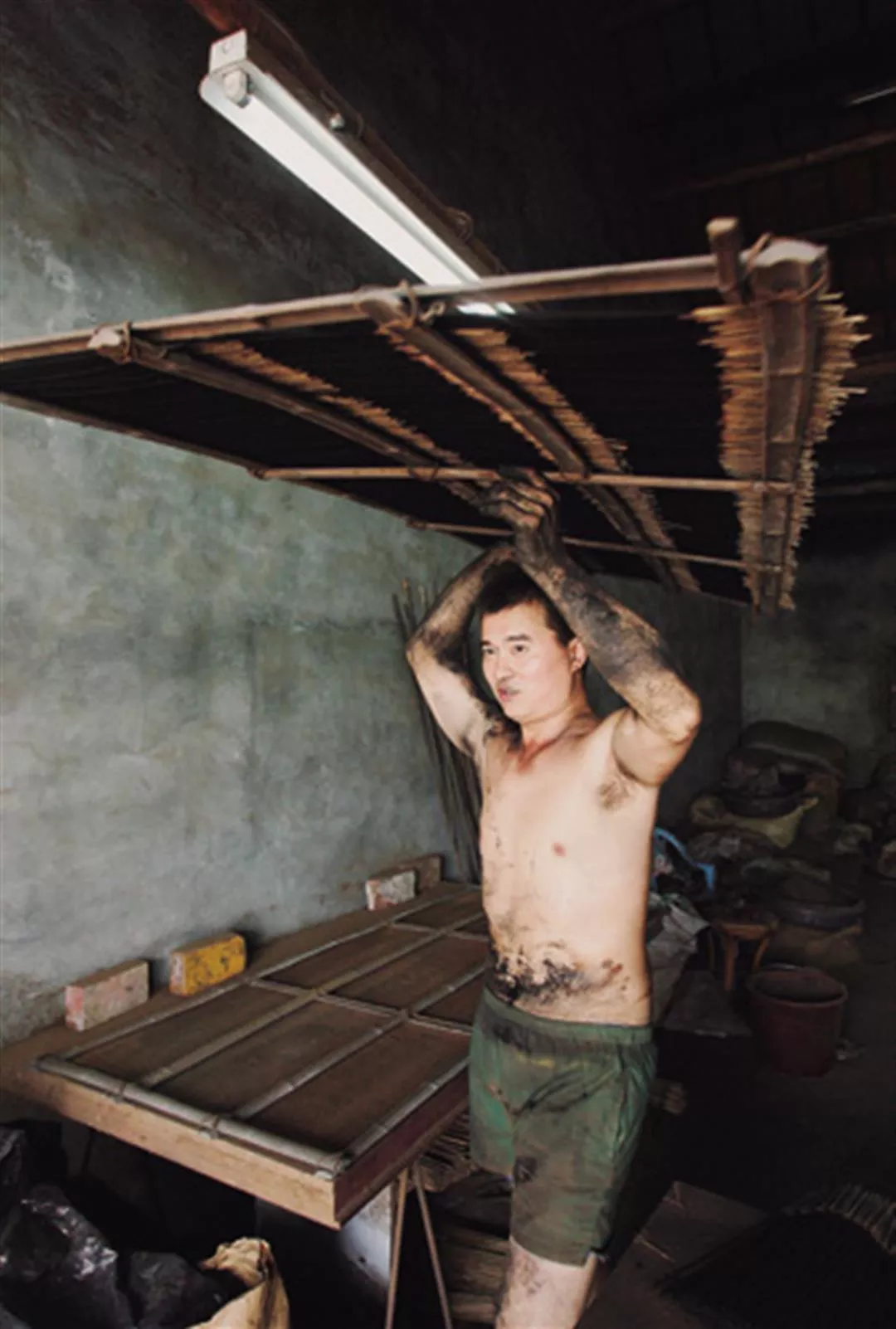

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

Tricks of the trade

"It's only when you take the raw material of agarwood or sandalwood, mill it, and then add as many as 20 kinds of other ingredients according to our ancestors' formulas and under the sure-handed control of master incense makers that can you produce the top-quality stuff," says Shih Chi-hsun. Incense made from pure agarwood has a light, subtle aroma. To highlight it, you've got add some "seasoning." Like chefs preparing a signature dish, success or failure depends on the deft use of seasoning.

For example, scented ingredients, such as musk, civet, castoreum and ambergris, may be added to sandalwood or agarwood incense powder. And various herbal ingredients from Chinese medicine, including clove, cumin, star anise and rhubarb, might also be added. There are countless variations on how these components can be used.

Different makers use different formulas. They may vary the proportions of ingredients or mix and match differently to create unique winning combinations. When asked about the secrets to Shihchinyu Sanfang's one-of-a-kind incense, the old master answers succinctly: "It comes down to experience." But for consumers who lack expertise, all this talk about "tricks of the trade" and "secret ancient formulas" isn't particularly helpful. With low-quality incense from mainland China and Southeast Asia flooding the market, how can buyers distinguish between the good stuff and the bad stuff?

"Most of the incense sold in shops in Lukang," says Shih Chi-hsun, who has been manufacturing incense for 45 years, "is made either from agarwood imported from Vietnam or sandalwood from India. Both are natural ingredients to which no chemical aromatics are added. The ash left over from high-quality incense is not hot to the touch, and the aroma will refresh the mind and make the whole body feel comfortable."

Among previous proprietors of Shihchinyu Sanfang, the fourth-generation boss lived to 130 years and the fifth generation to 93 (although the sixth only made it to 70). Their longevity suggests that not only is natural incense not cancerous, but it can in fact help one to live to a ripe old age. Incense is only harmful when unscrupulous people in the industry don't follow the proper ways and use chemical additives.

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

Natural is best

Shih Chi-hsun explains that the best way to judge whether incense is good or bad is to light it and then smell the aroma. Good incense won't have a sour smell or irritate the nose, and its smoke won't irritate the eyes and cause them to tear. If ashes from the incense that fall onto the hand have a scorching feel, then the maker added lime. The ashes from low-quality incense containing chemical additives are much lighter in color.

"Natural incense employs ground-up rotten sweetgum wood, which is infused with aromatics, to help the incense burn, whereas the low-quality stuff typically uses lime, which adds weight, thus giving the false impression of higher quality, and increases the speed at which it burns," says the boss's wife Hung Pao-chen. And the aromatic essences and fuel additives in the low-quality stuff emit butadiene and benzene, known carcinogens whose toxicity increases five to seven times when burned. "Poor-quality incense uses inferior ingredients, so naturally it is inexpensive. With a large pack selling for NT$20, it's more than 50 times cheaper than top-quality agarwood incense, for which a small pack will sell for NT$1000."

"Making good incense brings good fate," goes the Shih family motto, "and burning good incense builds good karma." Hung argues that manufacturing incense is a business with a conscience. The shop relies on its history and trustworthiness to keep afloat. There is a moral element to the endeavor, and also a sense of family mission.

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

The dust flies

From their store on Lukang's Fuhsing South Road, their 95,000-square-foot factory is on the other side of a radio transmission tower. There, Shih Yeh-chih, 30, the store's able-bodied and nimble eighth-generation leader-to-be, has taken a bunch of more than 100 sticks of incense that have already had sticky powder applied and been dunked in water. He keeps turning them over in the incense powder and applying pressure from between his thumb and index finger. Time and again, he fans them open and then pulls them back together. This movement is called "swinging the incense fan." While opening and closing the bunch, the incense powder becomes evenly applied to the sticks. Then, the sticks are dyed red on the incense legs and taken to the courtyard outside to dry in the sun.

"Basically, making incense depends a lot upon the weather," says Shih Yeh-chih. "In southern Taiwan we've got ample sunshine, so typically it requires only one day to dry in the summer, but it takes two in the winter." Back in the summer between high school and university, Shih Yeh-chih began to study the trade, but then gave up because it was too arduous. An ability to distinguish between good and poor quality incense materials is far from all that is in a master incense maker's skill set. Sufficient arm power is also important because "swinging the paper fan" taxes one's strength and endurance. Consequently, most incense makers are men.

Other steps in the incense making process, such as mixing the incense materials and dipping the incense sticks, used to require a lot of arm power as well. Although machines can do much of that now, there are still some steps, such as the dyeing at the end, where if your wrist power isn't sufficient and you drop the bunch, then all your previous work will be for naught. Tung Pao-lung, an incense maker who has worked at Shihchinyu Sanfang for 15 years, has a right arm that is markedly larger than his left. What's more, when you mix the ingredients for incense, you've got to sprinkle in incense powder, so that the room often grows covered in dust. If producing large quantities to meet seasonal demand, the maker's face will grow darkly coated with the stuff. The profession has an unglamorous appearance-one seems to struggle to make a living all the while covered in dust-so it naturally doesn't attract many youths.

Whether from incense sticks, coils or cones, the aroma of the swirling incense smoke clears the mind and eases one's burdens.

Sunset industry?

With this generational fault line appearing at a time when many traditional skills are being lost and Taiwan as a whole is experiencing an industrial transformation, it would be easy to imagine that this century-old shop would be facing its final days.

"When business was booming, our factory employed eight people and produced 30,000 pounds of incense a month, and we still couldn't meet demand. One fully loaded 2.4-metric-ton truck equaled NT$1 million in sales. Now we employ only one incense maker and produce just 3,000 pounds a month-about of a tenth of what we did back in the day."

Hung Pao-chen explains that in the 1970s when the Taiwan economy took off, temples were being erected, and people were constantly praying to the gods or holding religious ceremonies. The incense business flourished. But then low-priced incense from mainland China flooded the market, which led directly to the industry's decline in Taiwan. "At the peak, Lukang had more than ten producers of incense. Now there are still many incense shops, but very few indeed that still makes their own incense."

Three years ago Wen Wen-long, an instructor at Lukang Community College, offered Shih Yeh-chih this line of encouragement: "Making incense isn't a profession but rather a cultural mission." It inspired the younger Shih to abandon the suits and ties and air-conditioned offices of white-collar work. Instead, he chose to enter the family business and embark on a many-faceted transformation of it. To keep the business going, he is pushing for it to abandon its family-business scale (with one shop and one small factory) and boldly move in the direction of a modern commercial business.

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

A turning point

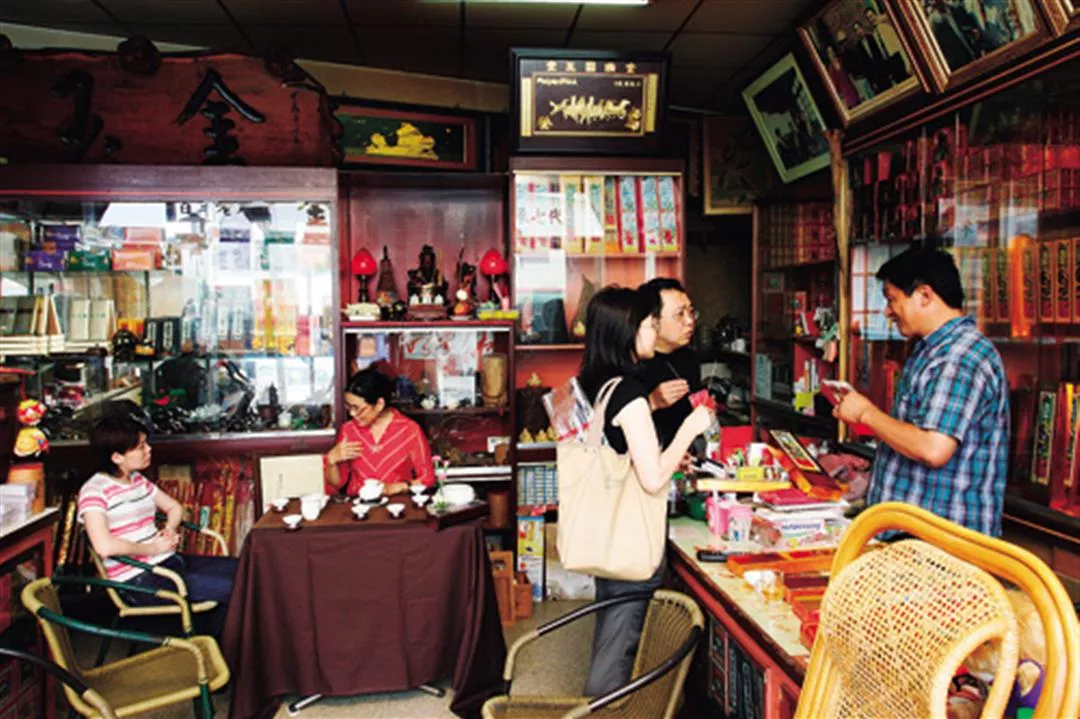

As part of that shift, they have added Internet and telephone ordering with home delivery. And Shih Yeh-chih and his wife have opened up new sales channels through department stores, with the aim of reaching a new kind of customer. Last year, when their incense debuted at the Shin Kong Mitsukoshi department store in Taichung, there were sales of NT$400,000 in just 14 days. It provided a financial boost and earned Shih Yeh-chih his elders' trust.

As for product diversification, Shih Yeh-chih says that incense had long been broadly regarded as belonging to the realm of faith and the spirit world, and that people's conception of incense was confined to the large brass incense-holding cauldrons found in temples and the swirling incense smoke when people went to pray. But thanks to the fashion for Eastern spiritualism, artists, writers and scholars, both in Taiwan and abroad, have raised the status of incense, turning it into a from of tasteful refinement or a lifestyle choice. It is even being used in aromatherapy and other calming alternative therapies. That is the way of the future.

Moreover, holding to its mission of keeping traditional skills alive, Shihchinyu Sanfang is promoting "knowledge tourism" and opening up the factory for public tours. The Shihs hope that the tours will both educate the public about the traditional art of incense making and also bring new vitality to the old establishment.

"The younger generation have truly brought new life to this century-old business." Most people believe that incense manufacture is a sunset industry, and that most young people aren't willing to enter the field. Shih Chi-hsun and Hung Pao-chen rejoice that their son has been willing to receive the torch. Even if in an old family firm there are generational differences about running the business and marketing its product, and quarrels among brothers over how to divide the family business and who is the authentic heir to the tradition, from the confident way that Shih Yeh-chih talks about the future blueprint for Shihchinyu, and from the smiles on the elder Shihs' faces when they speak of their son, one can sense a generation gap closing and a new chapter being written in the history of this old firm.

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

From mixing the powder, wetting the incense sticks, dipping the sticks, and "swinging the incense fan" to smoothing the insence sticks in a machine, the process of making incense is complicated and physically taxing. It is a traditional craft in a state of crisis. In these photos, the master incense maker Tung Pao-lung sho+++ws how it is properly done.

Whether from incense sticks, coils or cones, the aroma of the swirling incense smoke clears the mind and eases one's burdens.

Making incense is both physically taxing and dependent on the weather. Thanks to a sense of cultural mission, the tradition of making incense has survived through two centuries. The photo on the facing page shows Shih Yeh-chih (right), the eighth generation in his family to work in Shihchinyu Sanfang. He is preparing to take over the business so as to keep traditions of incense making alive.

Whether from incense sticks, coils or cones, the aroma of the swirling incense smoke clears the mind and eases one's burdens.

"Making good incense brings good fate, and burning good incense builds good karma." The Shih family motto explains why incense making in Lukang hasn't died out. Shih Chih-hsun in on the right and Hung Pao-chen is second from left.

Sandalwood and agarwood are the principal materials used in the incense that the Shihs make. To these they add some 20 aromatic ingredients from their unique formulas. They use no chemical additives, which people are concerned may lead to cancer. The photo shows the process of manufacturing incense coils.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)