Those are family trees etched in their faces so they and their descendants won't forget that they are Atayals--from birth to death, generation after generation, forever.

Of the nine tribes that still exist today (thus excluding the plains tribes that have already become completely sinified), there is documentation of tattooing among six: the Atayal, the Saisiyat, the Paiwan, the Rukai, the Tsao and the Puyuma.

Only the Atayal and the Saisiyat tatoo primarily on the face, using similar designs.

The Saisiyat, however, only tattoo as a result of their being enemies of the stronger Atayal. They see tattooing as a form of self protection, something they feel compelled to do. But they have no deep cultural tradition of facial tattoos, and Atayals were often employed to do the tattooing for them. It is the Atayal who have the long tradition of facial tattoos.

And so it was that in an early Ching Dynasty document, the Atayals were called the "face-tattooing barbarians."

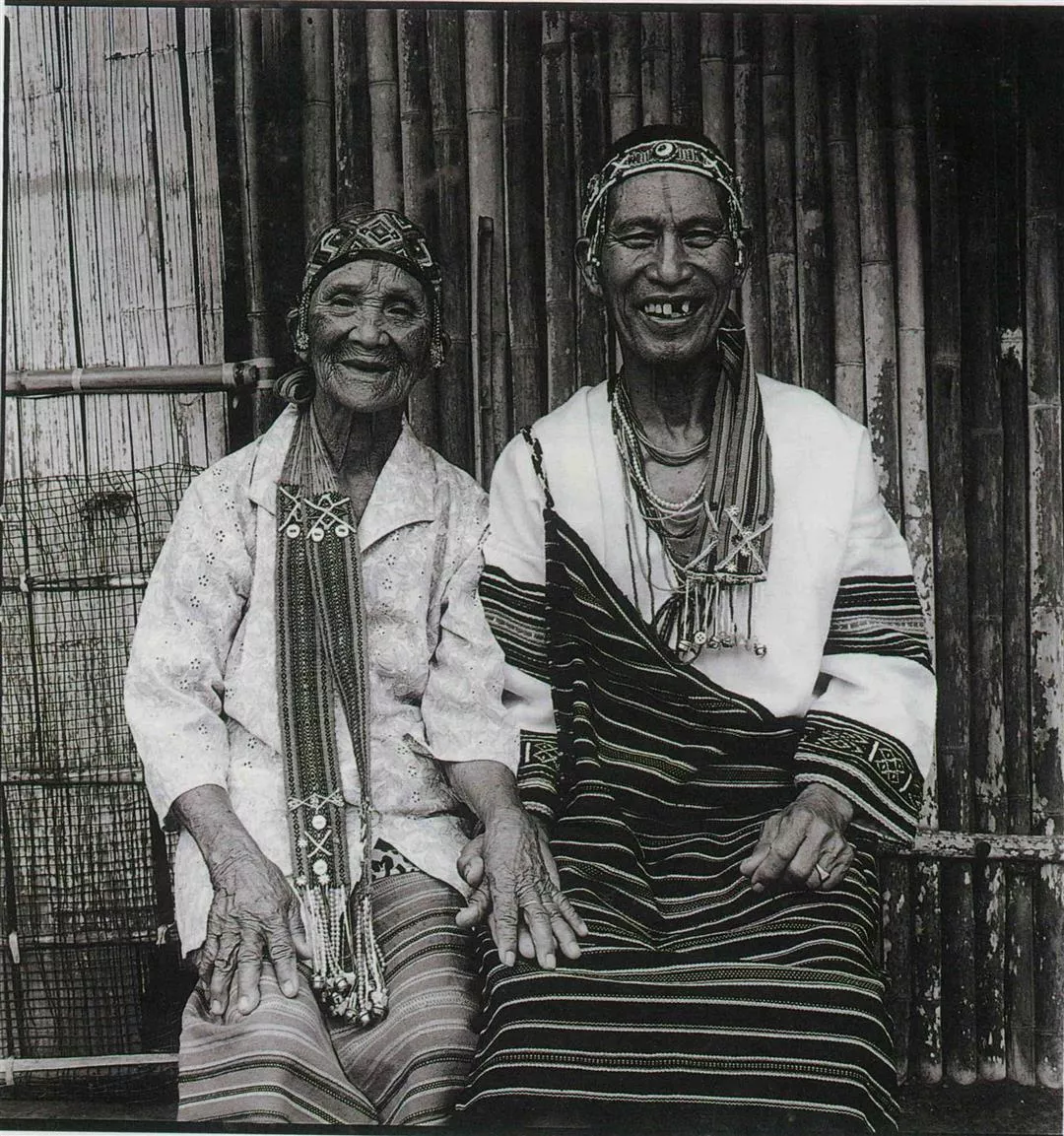

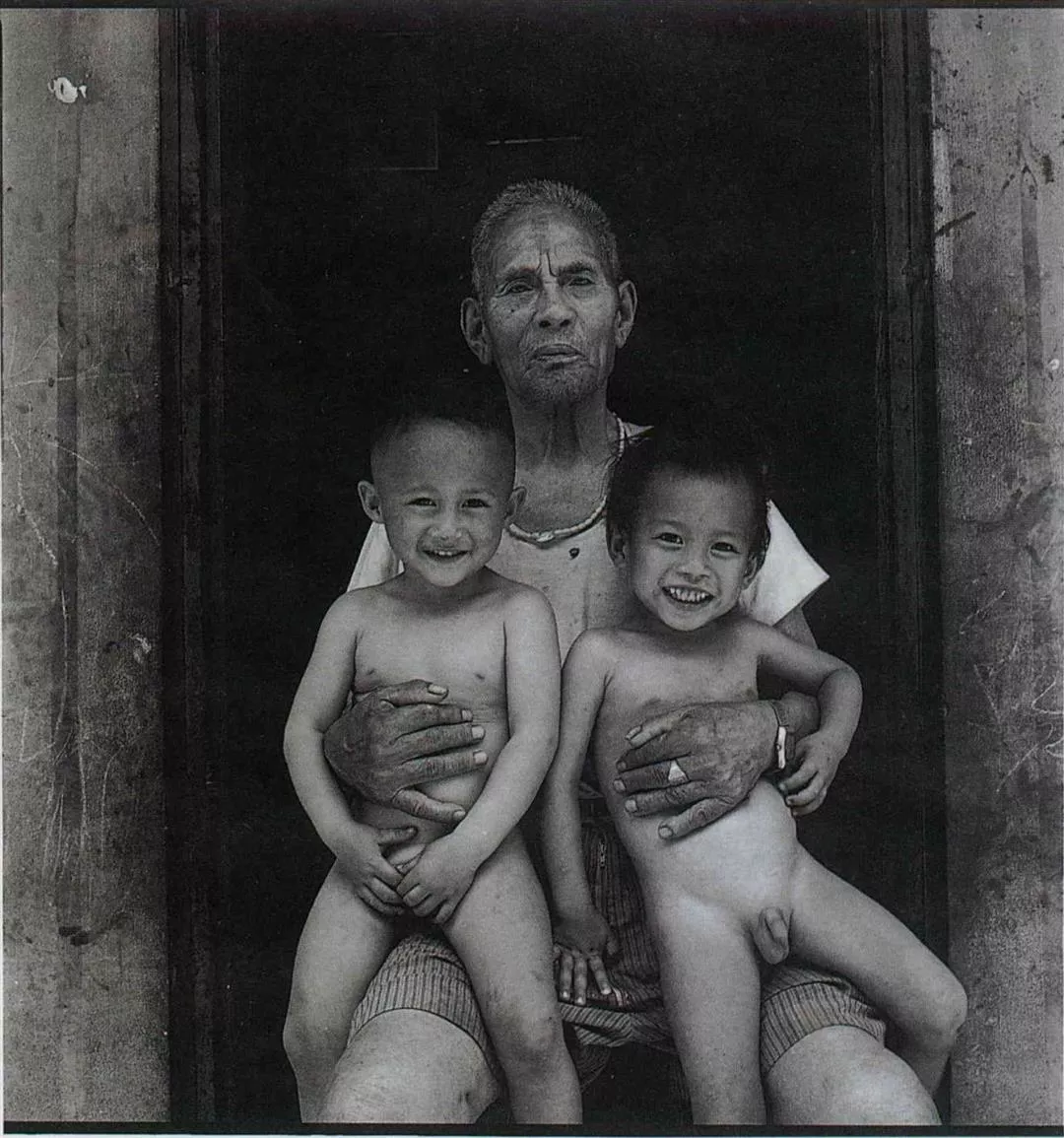

Baai Yawi, 82, was tattooed when 23 and married two years later. When he was approached for this interview, he was making a rattan rucksack and continually complained about the lack of rattan in the mountains. He learned Hakka from workers who came to the mountains when he was young.Ali Va'ai, 79, was tattooed when she was 18. She married twice and has one son and four daughters.

An ancient people

In anthropology, the Atayal are classified as an Austronesian people, which is one branch of the Indonesian family. Scholars see such Atayal cultural traditions as patrilineal inheritance of names, frame architecture, face tattooing and head hunting as evidence that they are descended from mainland China's ancient Yueliao people. As recently as five or six thousand years ago, they crossed the strait from mainland China to Taiwan, landing on what is now the west coast, where they settled in the plains. Later they moved to the tablelands and foothills, and then went up the river valleys to where they can now be found in Nantou County deep in the Central Range. Here they proliferated, and as the tribe grew ever larger, it expanded to all sides. Early arrivals to Taiwan, they encountered less resistance, and they are now spread across half of Taiwan's mountainous interior.

The Atayal were once the most fearsome people of the mountains, occupying lands stretching from Jenai Rural Township in Nantou and Chohsi Rural Township in Hualien north through the central mountain range to the slopes of Snow Mountain. They lived at elevations between 600 and 2000 meters, and engaged in slash-and-burn farming and hunting.

This dangerous environment shaped the courageous determination of the Atayal and gave them an ethnic abhorrence of compromise. The scarcity of land and resources made them very territorial. Staking out their own realm, Atayal clans would incessantly be at war with other tribes and clans. In order to survive, the rules governing the clans put heavy restrictions on the individual. Each tribal village was a well trained fighting unit.

The character of the Atayal made them the most difficult of all of the aboriginal peoples to rule. They fought countless wars against subjugation. For instance, the Atayal were behind the Wushe incident of 1915 and the Taroko Gorge War, which claimed the life of the fifth Japanese governor general of Taiwan. Such history is the source of great pride to the Atayal people.

But as the Atayal have adapted to the world of the 20th century, their ways of life have been completely transformed.

Cultivation of fixed plots has replaced nomadic agriculture and hunting.

Those who were the fiercest hunters of the mountains are now mostly members of the lower strata of urban society, socially marginal workers and drivers.

Traditional beliefs about ancestor spirits that have been passed down for thousands of years were overturned by Christian theology in just half a century. The country village has replaced the traditional system of the clan.

Many tribes have moved from deep within the mountains to tableland near the plains and now have deepening interaction with Han Chinese.

As capital from the plains has made its way into the mountains, many Atayal tribesmen have sold out to become hired hands on what was their own land.

As their traditional ways have died out, a new generation of Atayal have become strangers to their own culture, lacking confidence in and understanding of their own people.

Currently the Atayal are spread across an area encompassing Taipei County's Wulai Rural Township, Taoyuan County's Fuhsing Rural Township, Hsinchu County's Wufeng and Chienshih rural townships, Miaoli County's Taian and Nanchuang Rural Township, Taichung County's Hoping Rural Township, Nantou County's Jenai Rural Township, Hualien County's Hsioulin, Wanluan and Chohsirural townships, and the Tatung and Nanao rural townships of Ilan County. The tribe has the widest spread of any of Taiwan's indigenous peoples.

Currently the total population of Atayal stands at about 83,000, placing them second to the 140,000 Ami among aboriginal tribes.

The Atayal are now split between two different sub-tribes, three dialect groups, seven different lineage groups and 27 clans.

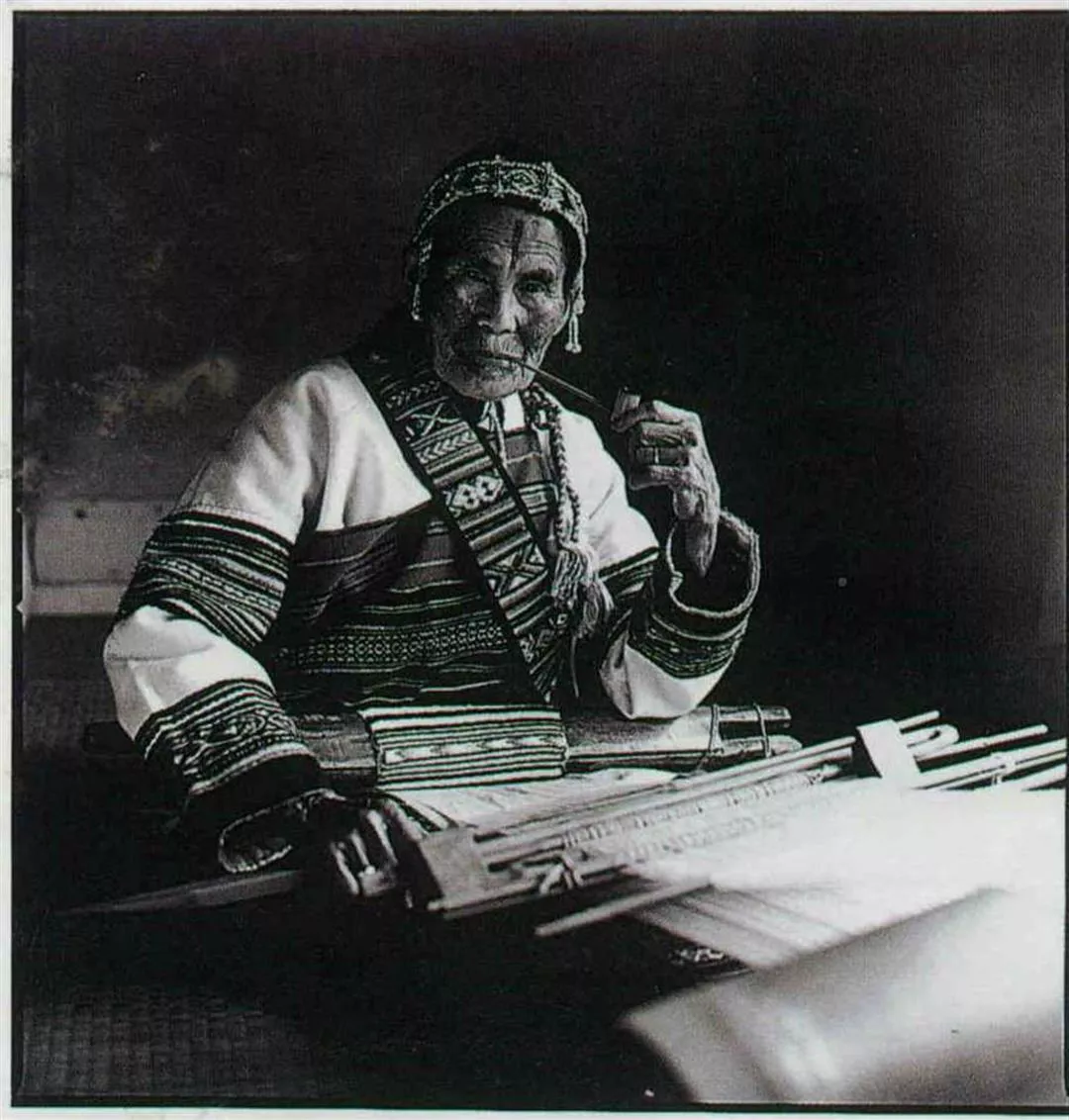

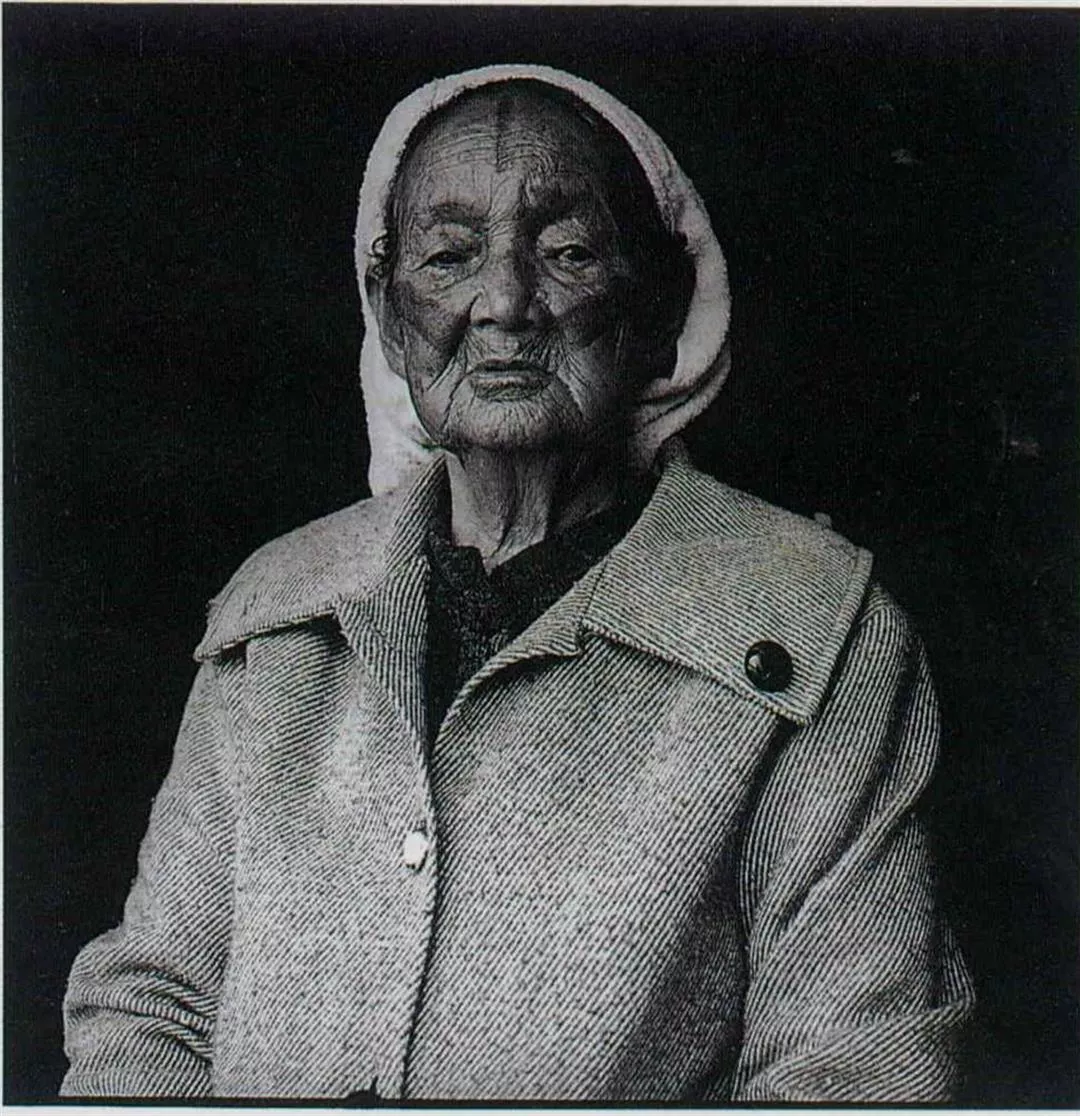

Ba'ah Haki, 84, was tattooed when she was 15.

Their ancestors' promise

Those descended from the Yueliao people in mainland China have already been sinified for several thousand years. But here in the mountains across the Taiwan strait, the Atayal have for thousands of years passed along the customs their Yueliao ancestors brought with them from the mainland.

Among the different Atayal sub-tribes and dialect groups, some evolved traditions and languages that differed greatly from those of their ancestors; others hardly changed a whit.

Tattooing was one of the most pervasive and representative traditions passed down from their ancestors. No matter which branch or clan of the Atayal, no matter how far they travelled, in which deep mountain valley they lived, those marks would be on their faces. It was the same for thousands of years. They were like family trees etched into their faces, a legacy of generations never at rest.

Different clans and sub-tribes had different legends about the origins of the Atayal facial tattoos, but two basic stories were widely known.

In the beginning of the world, a large rock suddenly split in two, revealing a man and a woman.The two lived together as older brother and younger sister. After a time, the sister realized that they must propagate future generations, and so she blackened her face with charcoal so as to trick her brother into thinking she was an outsider and arouse his passions. A version of this story was shared by all of the Atayal; it's just that in some cases the main characters were a mother and a son and in others an older sister and younger brother.

Another common legend is that when people die, their spirits must go across a rainbow bridge. Atayal ancestors stand at one end of the bridge welcoming their descendants to their spirit world. The facial tattoos mark an agreement that signifies your ancestors' promise to meet you when you die.

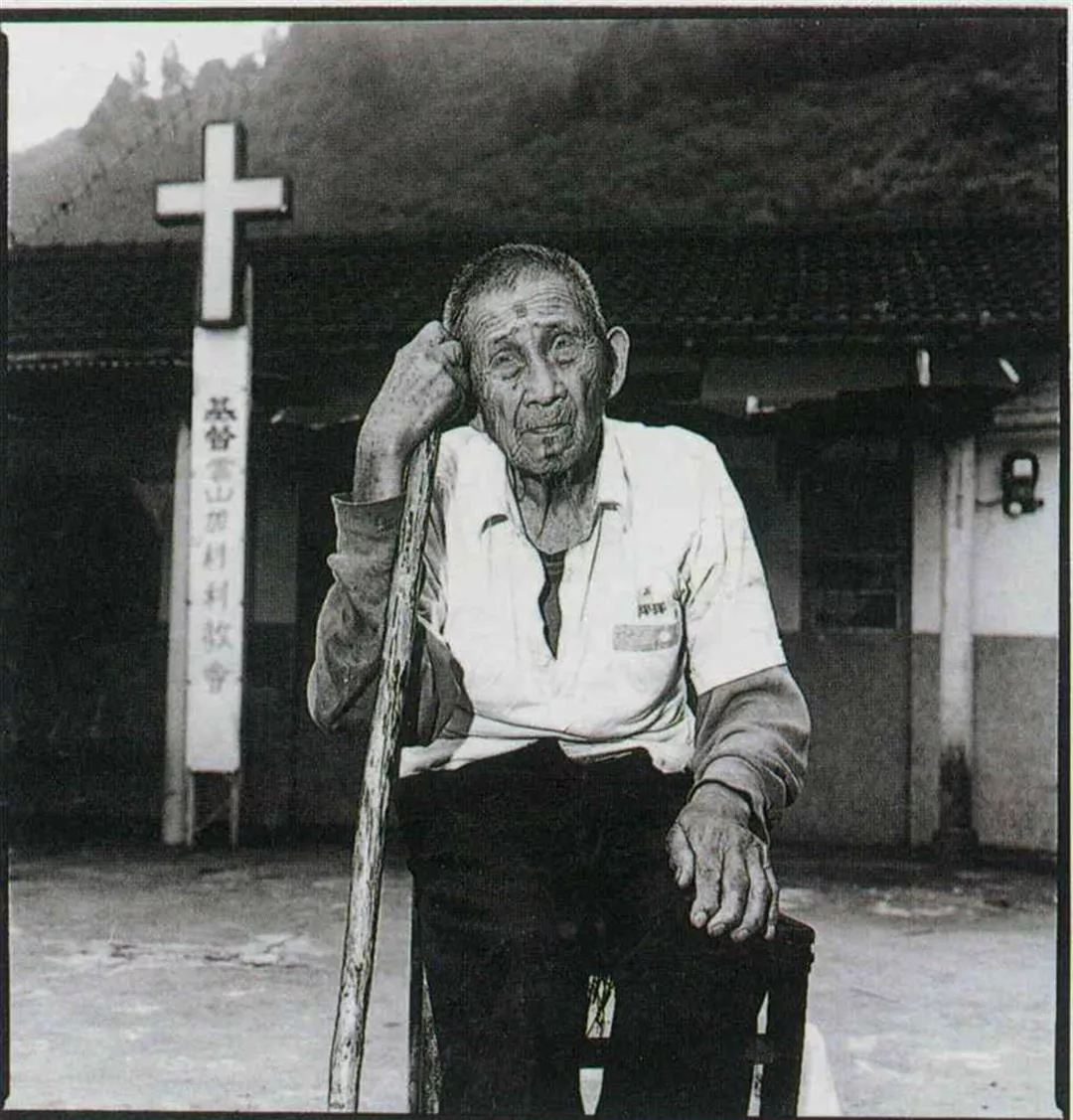

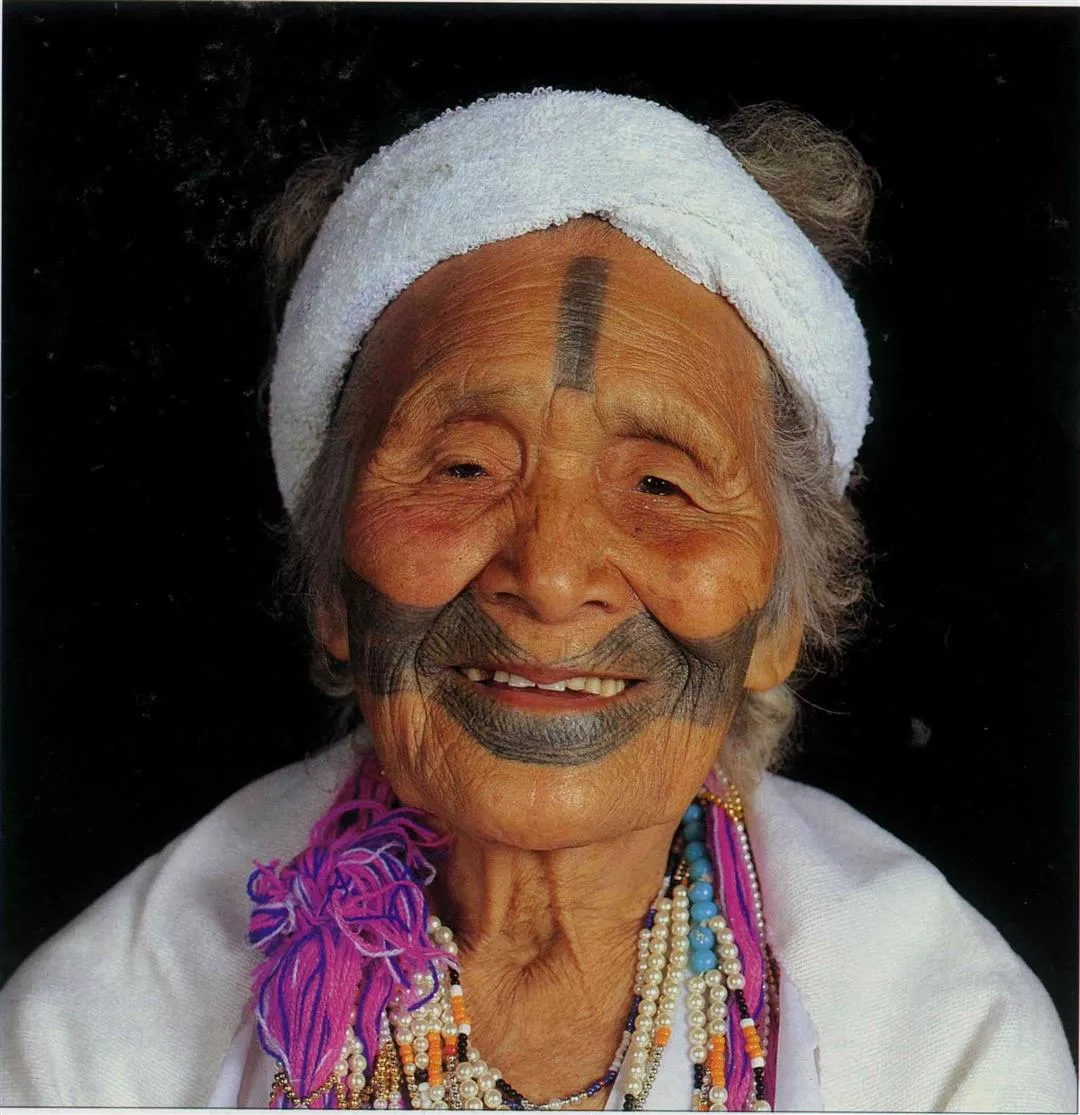

Because of serious illness, Suyen Navut, 98, has lost his powers of speech.

Their function in tribal society

There is no way to ascertain the true origin of the facial tattoos, but in the Atayals' daily lives they did have great social meaning and function, including distinguishing tribal origin, announcing the coming of age, beautifying the appearance, preventing the spread of evil, signifying bravery and displaying the height of feminine weaving skills.

Whether boys or girls, Atayal children would first be tattooed on their forehead for the purpose of distinguishing their clan (though a few clans would wait until the coming of age ceremony). After the males were full grown and had gone out on a head hunt, they could have a tattoo put on under their lips as a mark of their coming of age and their bravery. When the women were full grown, they would have to pass the weaving and farming tests before tattoos would be placed on their cheeks to show their maturity. And neither men nor women could marry until their facial tattoos were complete. For the tribal villages, the tattooing helped to raise productivity and cultivate the ability to make war; it was a well spring of tribal power. For the individual it represented the moving on to a new stage of life.

In the tribal society of years past facial tattoos were full of significance, at the heart of the Atayal tribal customs and individual experience.

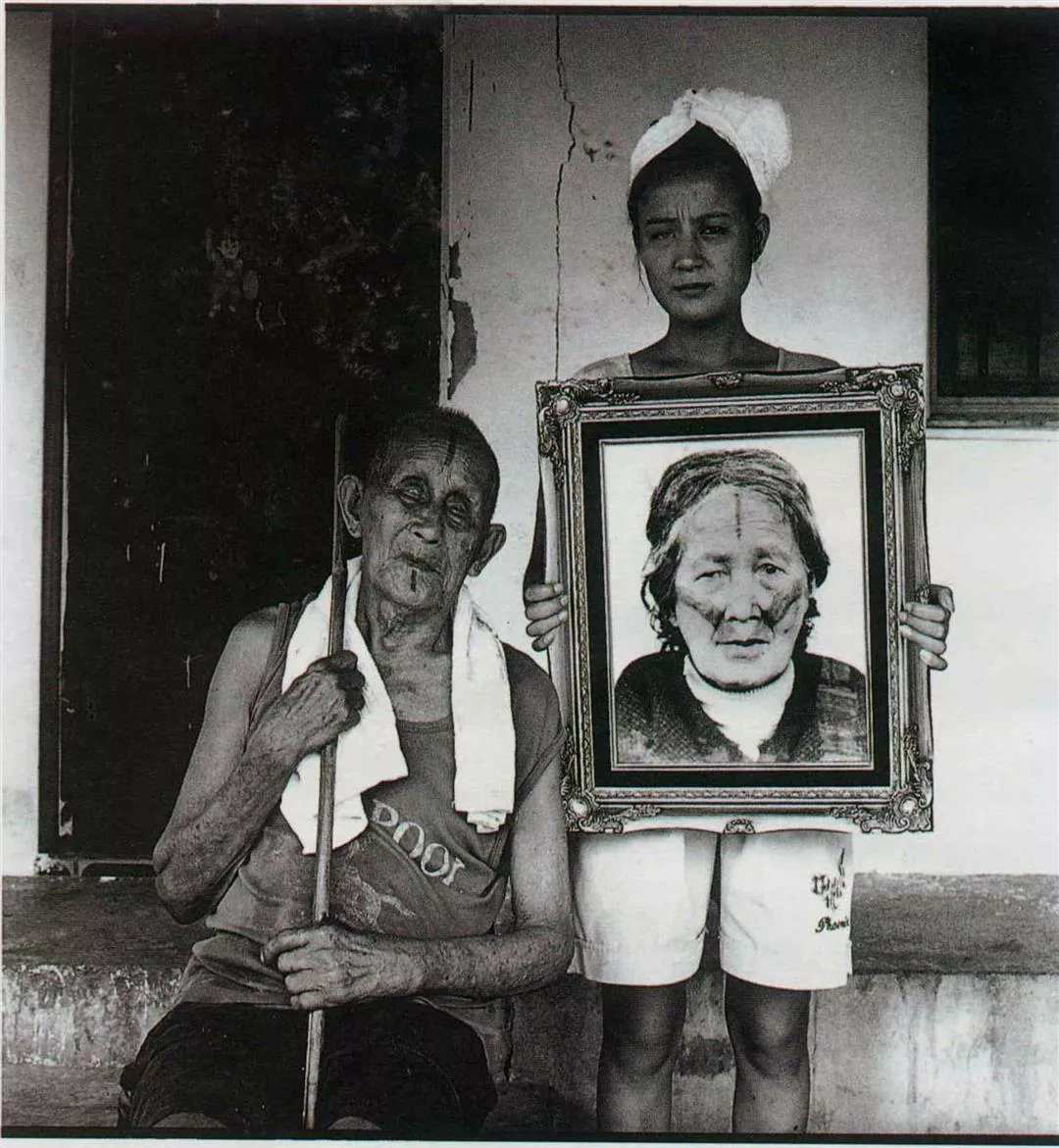

Mahsin Yuming, 101, was tattooed when he was 14. His wife died just last year.

The process and method

The tattooing itself was a very complicated process. Usually when children came of age, the parents would find an omen in their dreams to determine the day and hire a madas or tattoo master. Before the tattooing, they would also divine by interpreting the voices of birds to see if all would go well.

First they used hemp thread stained in charcoal to draw a pattern on the face. Then they placed a toothbrush-like tool with several rows of iron needles on the area of the face to be tattooed, hitting it with a wooden mallet two or three times to push the iron needles through skin. Then charcoal was rubbed into the wounds, allowing black coloring to soak into the wounded areas.

It was an easier and shorter process for the men, usually no more than a morning. For the women, more complicated tattoos drew out the process to more than ten hours. Usually they'd start early in the morning and not be finished until dusk. It's easy to imagine how painful it must have been. Because they didn't use antiseptics, the women's cheeks would swell for 10 to 20 days afterwards. They'd survive on soups and porridge, not being able to get solid food down.

Before their wounds from the tattooing healed, they couldn't go outside or meet with outsiders. After about one month, when the wounds healed and the scabs flaked off, a dark mark, blue to black, was left behind, and it would accompany them for the rest of their lives.

Ago Wuda, 87, was tattooed when he was 15.

The Japanese put an end to it

In 1895, in accordance with the treaty of Shimonoseki, the Japanese formally occupied Taiwan, and after they gradually quelled resistance to their rule in the plains, beginning in 1906 they embarked on nearly ten years of "pacification" and "management" of Taiwan's aboriginal peoples. The"pacification" emphasized posting troops in every tribe in order to control then, and putting them in compounds surrounded by electric fences. By"managing" the tribes, they meant doing their most to subjugate every last aborigine and moving tribes from deep within the mountains to the foothills and tablelands closer to the plains, where they would be more easily controlled under the watchful eye of police.

Because the tattoos of the Atayal were closely bound up with their tradition of hunting heads, beginning in 1914, every time the Japanese subjugated a tribe, they first tried persuasion to get them to stop, before enforcing a ban on facical tattooing. Those who broke the law could be beaten, imprisoned and fined. But no matter how harsh the Japanese were in their punishment, there were always Atayals who would rebel against colonial power for the sake of preserving their custom of tattooing.

In the Wangyang tribal village of Jenai Rural Township of Nantou County, Baliagi Nogan, an 84-year-old tattooed woman who is a member of the Atayal's Saikaoliehko clan, says that she was just a girl when the Japanese started to come into the mountains. Her tribal village of Gayu (now Chiayang) was unwilling to submit to Japanese authority, and so they fled deep within the mountains and began a long war with the Japanese. In these difficult circumstances, with no set place to live and short on food, she was tattooed at her father's insistence.

In Hualien's Hsioulin Village, Biyang Dahang, a 93-year-old woman and member of the Saiteko clan, recalls that the Japanese established a police station in her Sgahen tribal village (along the upper stretches of the Liwu River) when she was just a girl, strictly enforcing the prohibition against facial tattoos. As the oldest daughter, she wanted to set a good example for her brothers and sisters. Believing she wouldn't be a good Atayal without the marks of her ancestors, she snuck off to the mountains to be tattooed. In punishment she was beaten by the Japanese.

And the Japanese government commanded Atayal all over the province who had already been tattooed to go to police stations, where doctors would use procedures to cut them away. They told them that with the tattoos they wouldn't look Japanese. This imperialistic practice reached its height during World War II. All of the Atayal drafted into the Japanese army were required to cut their tattoos away, so now in the faces of many old Atayal men there are only the colorless scars left behind from the removal operation.

The Japanese used great pressure to put an end to tattooing. But then in 1919, a terrible drought and flu epidemic struck the mountains of Taiwan, claiming many lives. Shaken, Atayal tribesmen thought the spirits of their ancestors were punishing them for not getting tattooed. And so some tribes took up the practice again. A similar return to tattooing took place after the Wushe incident. But these two short-lived periods represented the last hurrahs for a several thousand year Atayal history of tattoos.

Yawas Gumu, 83, was tattooed on her forehead when she was five and on her cheeks when 15, for which she was rebuked by the Japanese. By the time her tribal village was moved when she was 10, her parents had already passed away. She moved in with relatives, married at 20 and gave birth to one son.

The meaning in the lines

The basic forms of the facial tattoos were more or less the same for all of the Atayal clans--with the men being tattooed on the forehead and chin and the women being tattooed on the forehead and cheeks--but there are many small differences regarding the shapes and details of the tattoos.

Among the Saikaoliehko Atayal, for example, the lines on both the men and women were long and thin. The cheek tattoo for the women would stretch from the cheek bones down to the philtrum, the groove between the upper lip and nose. This was the smallest "V" found among any Atayals. The Tseaolieh Atayal had the thickest of lines. The cheek tattoos on the women started from right below their ears and went across their cheeks to their philtrums, forming a 90 degree angle. The tattoos of the Saiteke Atayal started from beneath the ears and crossed under the cheekbones to the philtrum, forming the widest angle among Atayal facial tattoos. The Degidaya of the Saiteko had three to six lines tattooed on their foreheads. Sometimes the tatoos would be in the shape of a cross or a Chinese character for king ( 王 ). Generally speaking, the farther north, the finer the lines became.

These variations provide evidence about Atayal migration and the spread of different Atayal clans. It's just unfortunate that no interdisciplinary study of facial tattoos was carried out in years past. A lack of pictures for future research and analysis is particularly vexing. Frustratingly, all one can do is sit and watch as respected tribal elders pass away one after another.

Facial tattoos were one of the oldest and most stable features of Atayal culture, a totem and salient characteristic of the Atayal people. Making a record of the culture surrounding these tattoos does more than provide academics with something to research. It will help give future generations of the Atayal a sense of tribal identity, and give the next generation of all Taiwanese more fertile cultural soil in which to extend their roots.

[Picture Caption]

p.92

Ali Hayun, 91, was tattooed on her forehead when she was four, and on her cheeks when she was 16 in exchange for clothing, woven cloth and yen. She married a year later. A widow, she has no children.

p.93

Lawai Siat, 70, was tattooed when she was 15 in exchange for millet cake, millet wine and beef. She married fellow villager Dali Noming and has three sons and two daughters.

p.94

Baai Yawi, 82, was tattooed when 23 and married two years later. When he was approached for this interview, he was making a rattan rucksack and continually complained about the lack of rattan in the mountains. He learned Hakka from workers who came to the mountains when he was young.

Ali Va'ai, 79, was tattooed when she was 18. She married twice and has one son and four daughters.

p.95

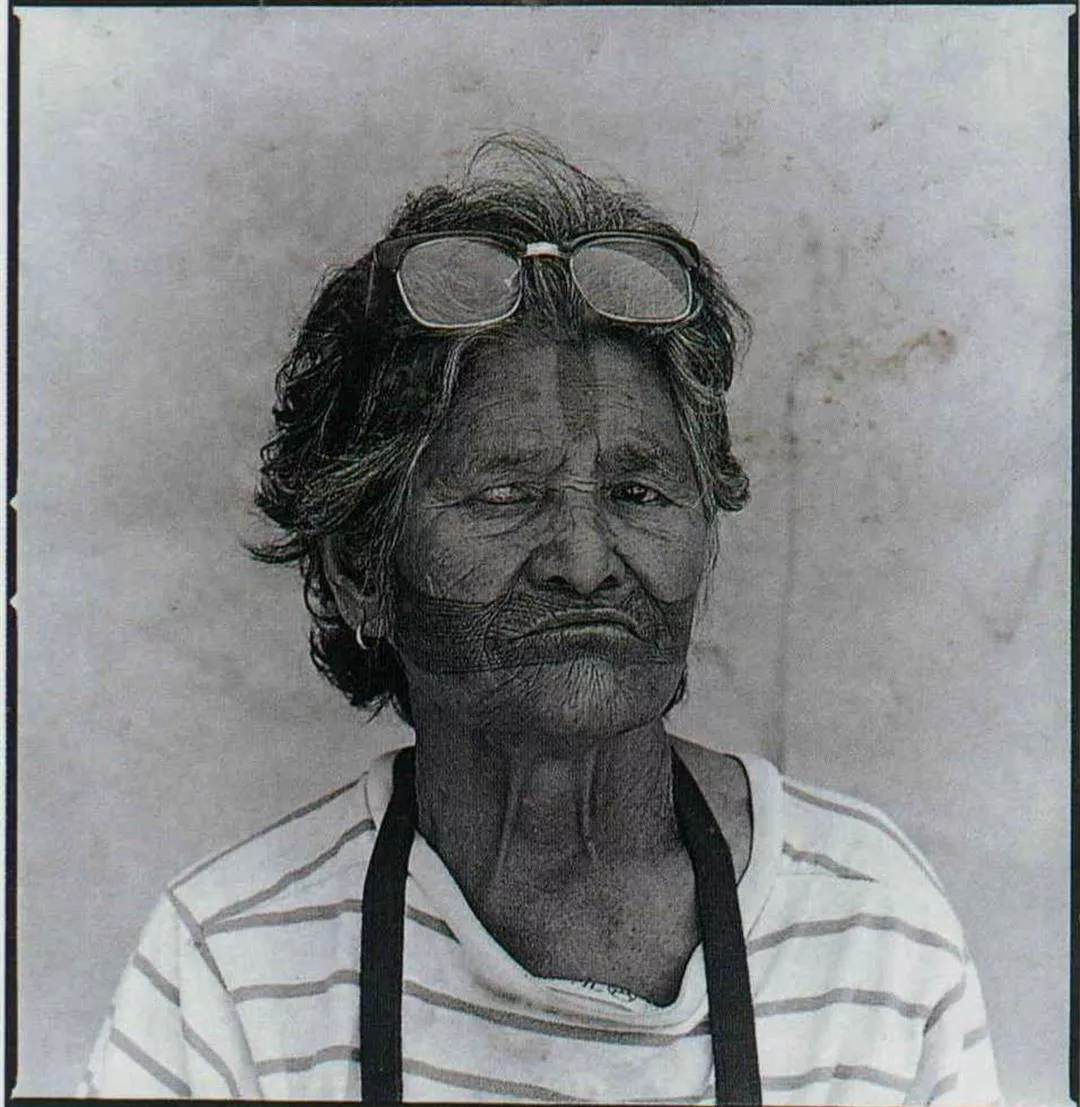

Ba'ah Haki, 84, was tattooed when she was 15.

p.95

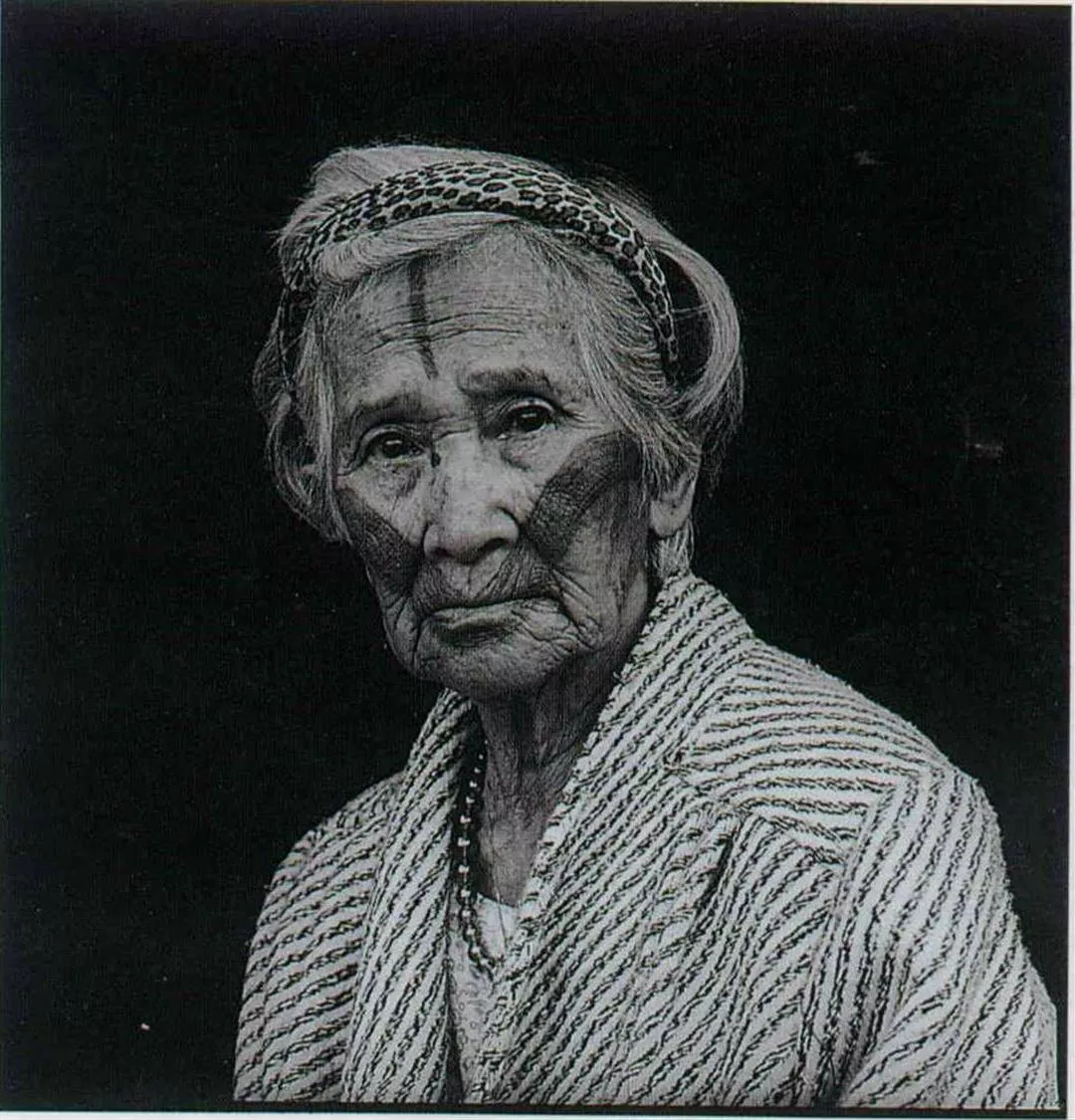

Because of serious illness, Suyen Navut, 98, has lost his powers of speech.

p.96

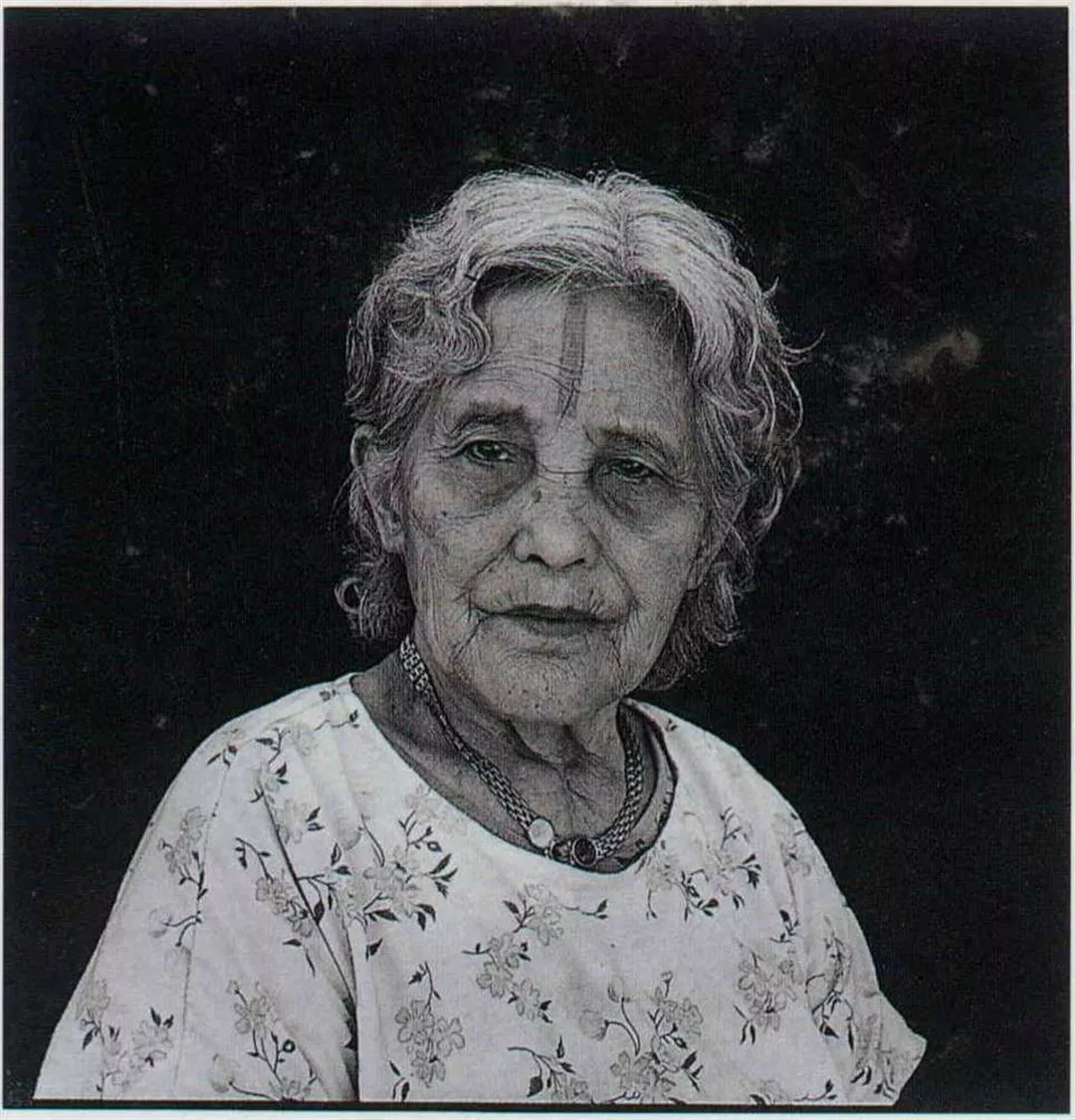

Mahsin Yuming, 101, was tattooed when he was 14. His wife died just last year.

p.97

Ago Wuda, 87, was tattooed when he was 15.

p.98

Yawas Gumu, 83, was tattooed on her forehead when she was five and on her cheeks when 15, for which she was rebuked by the Japanese. By the time her tribal village was moved when she was 10, her parents had already passed away. She moved in with relatives, married at 20 and gave birth to one son.

p.98

Lawa Bilang, 90, was tattooed on her forehead when she was 14 and on her cheeks two years later. A beautiful girl, her parents forced her to be tattooed, saying otherwise the Japanese would come for her. She still has frequent nightmares of being taken by the Japanese.

p.99

Budaun Gingin, 84, was tattooed when she was nine and married when she was 18. In her thirties, the Japanese moved her village to Malaibasi, where she converted to Christianity.

p.99

When she was 16, Lomei Gawein, 90, was tattooed on her forehead and then a month later on her cheeks. She paid with cloth and yen. She married when she was 21 and has four sons.

p.100

Ibai Wuming, 93, was tattooed on her forehead when she was six and on her cheeks when she was 14. She married at 20 and has six sons and two daughters.

Lawa Bilang, 90, was tattooed on her forehead when she was 14 and on her cheeks two years later. A beautiful girl, her parents forced her to be tattooed, saying otherwise the Japanese would come for her. She still has frequent nightmares of being taken by the Japanese.

Budaun Gingin, 84, was tattooed when she was nine and married when she was 18. In her thirties, the Japanese moved her village to Malaibasi, where she converted to Christianity.

When she was 16, Lomei Gawein, 90, was tattooed on her forehead and then a month later on her cheeks. She paid with cloth and yen. She married when she was 21 and has four sons.

Ibai Wuming, 93, was tattooed on her forehead when she was six and on her cheeks when she was 14. She married at 20 and has six sons and two daughters.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)