In the 2006 university entrance ex-ams, several pieces of Internet slang-such as 3Q (san Q, from the English "thank you") and Orz (an emoticon expressing desperation or defeat)-began showing up in questions. This apparent formal acceptance of the "moonspeak" used online stirred up no shortage of controversy.

The rise of this alien language has some taking a more punitive approach, while some are just disappointed, but there are also many who see this as much ado about nothing. No matter your perspective, one thing is undeniable-Internet slang's popularity isn't going to decline any time soon. And now that this train is rolling, what kind of sparks are likely to fly as Internet language steps out into the real world?

The idea of "moonspeak" is largely an Internet phenomenon-in English, it refers to unintelligible writing, usually in a non-Latin script, but its Chinese equivalent is writing in combination of numbers, punctuation, symbols, letters, zhuyin, and characters, somewhat akin to so-called "txt-speak" and leetspeak. Its simplicity and unique aesthetic have seen it grow in popularity, extending even into the world of handwriting, creating a new means of written expression.

Professor of Chinese at National Taiwan University Chou Feng-wu has conducted research into Chinese moonspeak, resulting in the paper "The Beauty and Sorrow of Moonspeak."

According to Chou, Chinese moonspeak began in online games, where players would mix zhuyin, Latin letters, and emoticons into their writing to save time and add character.

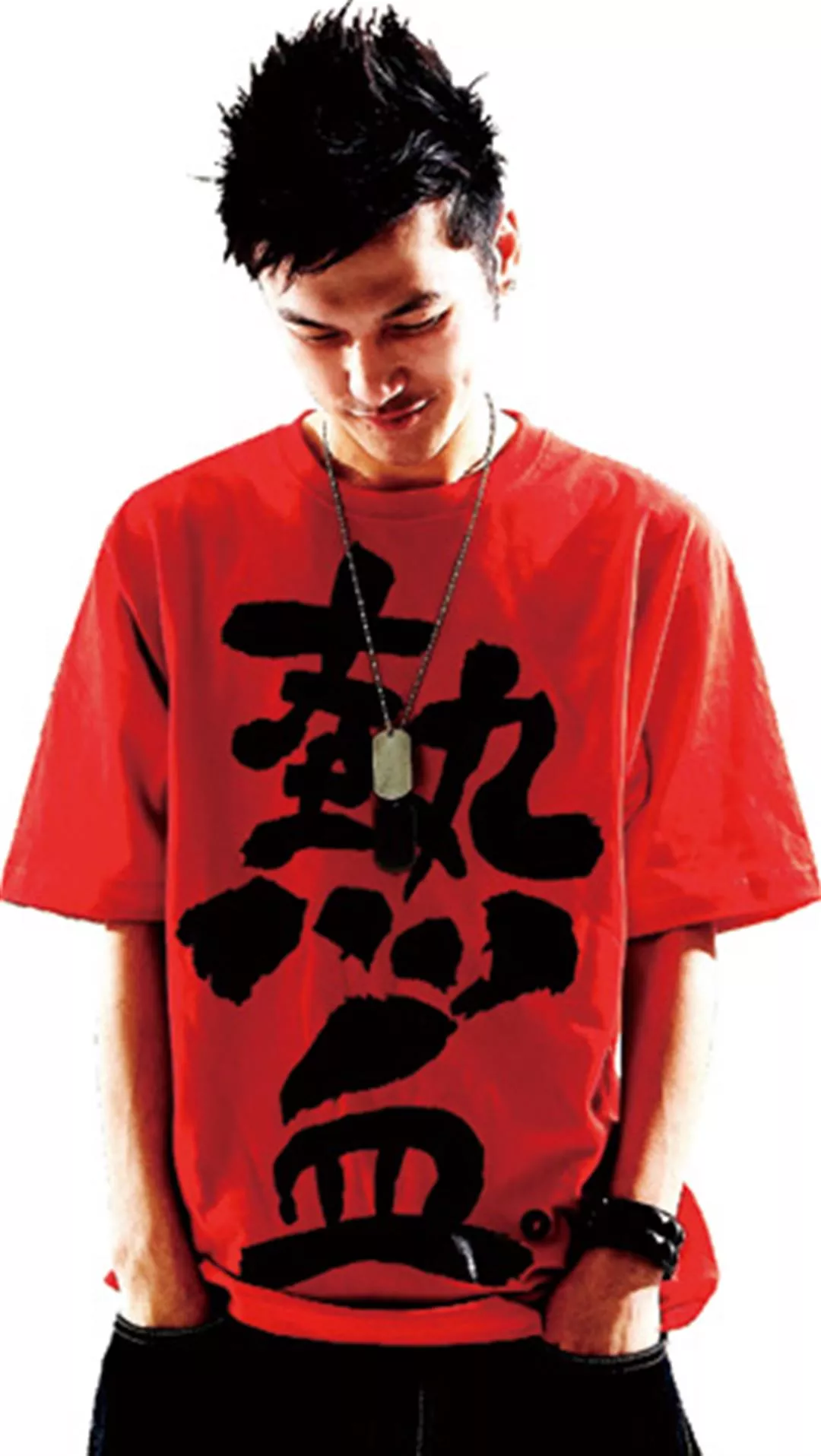

While some of this modern online "moonspeak" may be tortured use of language, and some if it may even be lei-"shocking," it's always rexie-hot-blooded-and vibrant.

One man's junk....

The Chinese for this moonspeak is literally "Martian language," and comes from the Stephen Chow movie Shaolin Soccer, where Chow, the male lead, remarks on the strange appearance of the female lead, telling her that she should go back to Mars because Earth is too dangerous.

With Chow's dialog popular on BBSes, it became common to see people respond to difficult-to-read or annoying posts with comments telling the poster to "go back to Mars," beginning the growth in popularity of the term.

Simplification is one of the central pillars of moonspeak. When using instant messaging systems like MSN or Yahoo! Messenger, if you want to quickly and interestingly express yourself in Chinese, you might use only the initial sound of a character (such as using the zhuyin £x, "de" to represent the character (tm)∫ (de, "of")), or perhaps a number, letter, or piece of punctuation that is pronounced similarly. Moonspeak is also marked by a combination of Mandarin, Taiwanese, and English, giving it a post-modern flavor. The same word can be represented in many different ways using this method, giving individuals greater freedom of expression.

What on Earth is CU29?

As Chou's research also notes, this form of writing is seen as beautiful by younger Internet users, but to those unfamiliar with Internet slang, moonspeak can be nothing by dismaying.

Oversimplification, though, can be seen as obfuscating and leave readers unclear what on Earth is going on.

If no-one explained it to you, you'd probably never figure out that "CU29" is "see you tonight," "3Q" is "thank you," "Jason loves Jason" is "jieshen zi'ai" ("self-control" from the Chinese first half, jieshen, and the literal translation of the second half, to love oneself), "AK4" is "e khi-si" (Taiwanese for "infuriating), "PMP" is "pai mapi" ("brown-nosing"), and "PMPMP" is "pinming pai mapi" ("brown-nosing for all you're worth"). Meanwhile, complicated Chinese characters are sometimes used to phonetically represent English words, such as using "√a?√a?√a?" (huai? huai? huai?-"bad? bad? bad?") in place of the English "Why? Why? Why?," the characters giving an extra sense of desperation.

Another form of simplification is the combining of two words into one, such as jiang being used as an abbreviation for zheyang ("like this"), or using biao as an abbreviation for buyao ("don't").

Emoticons are something largely unique to the Internet and other digital media. The two most familiar Chinese emoticons are Orz (a man on his hands and knees, head on the floor in desperation or defeat) and XD (which is a smiling face with eyes scrunched when rotated 90 degrees clockwise).

Don't blame the Internet

This lack of concern for accuracy in writing and the use of Chinese and English mixed together is commonplace online, but over time younger people may become used to these "mistakes," lowering the overall level of Chinese in Taiwan.

"This is an issue of education policy," says Liao Shuzhen, a Chinese teacher at Pingzhen Junior High School for over 20 years. The lowering of Chinese capability in students, she says, is substantially related to the sudden reduction in classroom hours, which for elementary students for example has dropped from 12 periods a week to only five. You can't blame it all on online slang; at most it is adding fuel to that fire and speeding up the deterioration.

The kind of language used in online chats has, though, begun to frequently appear in students' work.

Liao says she has noticed an increase in students using characters representing Taiwanese or Taiwanese-accented Mandarin and overly informal language in their work. Spelling the English word "feel" as "fu," a popular slang spelling, is also common.

"This is the language of the times, and no matter how hard you try and stop it or wipe it out, you can't change reality," says Liao, who describes such efforts as almost Sisyphean, and says that teachers would be better trying to figure out what the students are actually saying. Moreover, language changes over time; "I'm sure that even the vernacular baihua style of writing used by writers of our generation would probably be similarly looked down on by writers of the Tang and Song dynasties."

Cracking the code

Those already accustomed to using this "moonspeak" have naturally begun creating works using it. Well-known author Giddens (real name Ke Jingteng) has called this new language of creativity "keyboardese." "Just the same as writing with pen and paper, making use of the keyboard as a writing tool will naturally birth different kinds of language."

"The literature of each different era has its own different influences, and you can't simply apply the linguistic standards of the past to the present," says the 31-year-old Giddens. In his world, even the works of renowned martial-arts novelist Louis Cha are considered not particularly edifying, and now they're little more than part of that list of books recommended by teachers to students as a way to improve their Chinese.

While moonspeak may serve as a "secret code" for young people to communicate with, if the code becomes too complicated, it can become more of a hindrance than a help. Giddens notes that in his role as a literary prize judge in recent years, he has come across works using huge amounts of online slang, intentionally trying to look "odd," but ultimately rendering the books difficult to read and putting off readers.

Stanley, another online author, has mentioned in his essay "You've Got to Be Rexie [hot-blooded]" that one of the reasons he can't relate to young women today is that they use too much moonspeak in their letters, blog posts, and even their speech. This can make you feel like you're working as a codebreaker, cracking codes all day every day.

Regardless whether you think this new online language is beautiful or dismaying, the best way to deal with it is to just laugh it off, lol.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)