Remembering George Leslie Mackay

Chang Chiung-fang / photos courtesy of the Tamkang Junior High School Historical Archive / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

May 2001

How dear is Formosa to my heart! On that island the best of my years have been spent.

How dear is Formosa to my heart! A lifetime of joy is centered here.

I love to look up to its lofty peaks, down into its yawning chasms, and away out on its surging seas. How willing I am to gaze upon these forever!

My heart's ties to Taiwan cannot be severed! To that island I devote my life.

My heart's ties to Taiwan cannot be severed! There I find my joy.

I should like to find a final resting place within sound of its surf and under the shade of its waving bamboo.

-"My Final Resting Place" by George Mackay.

The ancient Greeks had four different words for love, which separately described love of family, platonic love between friends, the love between a man and woman, and the love of gods and deities. For George Leslie Mackay and other missionaries who decided to devote their lives to Taiwan before ever setting foot on the island, their love of Taiwan was the selfless love of God.

As the hundredth anniversary of Mackay's death approaches, perhaps examining his life will stir people to reflect upon what has become of Taiwan today, when the economy, society, and people's hearts and minds are all in turmoil.

During the 19th century, when gunboats brought foreign soldiers to Taiwan's shores in successive waves of invasion, the seas also brought Western missionaries who came with hearts full of love. The environment imposed enormous obstacles to carrying out their work, but their efforts left a big imprint on society and resulted in many praiseworthy accomplishments.

George Mackay was one such foreign missionary, and his name is still quite familiar to Taiwanese. Few, however, know much about his life.

Mackay was born in Zorra, Ontario in 1844, the youngest of six children. From an early age, he aspired to become a missionary. But when he stated his desire as a child, instead of being encouraged, he was called an "excitable youth" or "religious zealot."

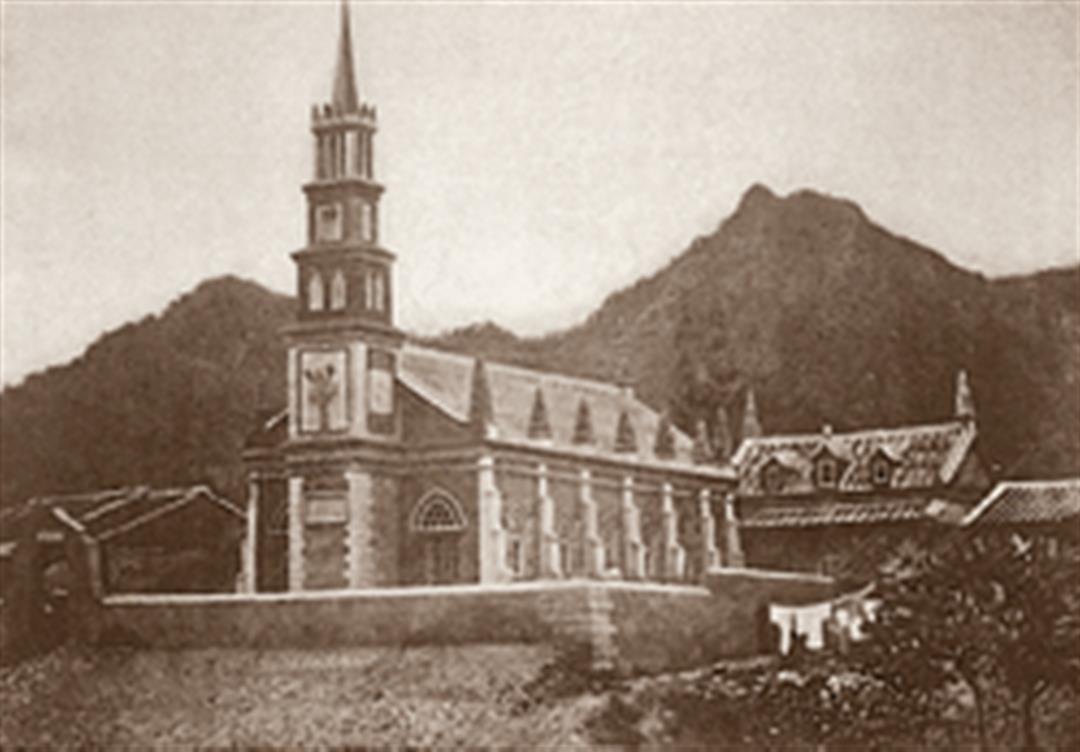

One of the churches that Mackay designed himself had a six-storied sharply pointed pagoda-like steeple, geometrical ornamentation on the walls, and gothic windows. It's an eye-catching mix of Chinese and Western elements

Identifying with Taiwan

In 1871, in the twilight years of the Qing dynasty, when men in Taiwan still sported pigtails and women still hobbled along on bound feet, George Mackay arrived here by boat from across the Pacific Ocean.

But Mackay wasn't the first foreign missionary in Taiwan. Dr. James Maxwell had established himself in southern Taiwan as early as 1865, so Mackay decided after arriving to make a new start in northern Taiwan.

In March of 1872 Mackay boarded the Hailung ("Sea Dragon") in Kaohsiung, and arrived in the northern port of Keelung three days later.

As the first missionary in the area, Mackay faced huge obstacles to accomplish even the smallest of tasks. We can only imagine how hard it must have been. In the view of Reverend Luo Jung-kuang, a Presbyterian minister, Mackay accomplished several very difficult things, including marrying a Taiwanese woman and learning Taiwanese from cowherds. Luo believes that these acts showed how strongly Mackay identified with Taiwan.

Mackay was a hard-working student of Taiwanese. In his diary, which he composed in romanized Taiwanese, he wrote: "I went to see those cowherds again, and learned vocabulary from them that you can't find in textbooks. They speak the vernacular, whereas as the language you find in books is Mandarin, spoken only by officials and scholars."

"There are no declensions or conjugations in Chinese, their place being taken by the 'tones,' of which there are eight in the Formosan vernacular. A word that to an English ear has but one sound may mean any one of eight things according as it is spoken in an abrupt, high, low, or any other of the eight 'tones.' Each one of these 'tones' is represented by a written character."

After studying for five months, Mackay was capable of conversing in Taiwanese. After 20 years, Mackay published a Taiwanese-English dictionary based on his thorough research.

Mackay's oldest son William described him thus: "Of average height and burly-chested, he was bold, knowledgeable and energetic. He had dark eyes, and his hair and beard were black too. His voice was strong and piercing, and he spoke with great confidence. He was a gifted speaker and had native-like fluency in Chinese."

Apart from his missionary, medical and educational work, Mackay also worked hard to compile written and visual records of the Taiwanese society of his day. These now comprise a precious historical resource. This photo taken by Mackay shows a farmer, assisted by his wife, using a wiinnowing machine to separate the rice from the chaff.

Open sesame

Despite all Mackay's effort and talent, in predominately Buddhist and Taoist Taiwan, there were times when crowds heckled him, or even threw stones or excrement at him.

"Many people gathered around us, shouting, 'A barbarians' religion. A barbarians' religion. Let's kill him. . . ."

"It was at Go-ko-khi, the first station established in the country, that the first Christian marriage was celebrated. The news that the missionary was about to perform a marriage ceremony spread rapidly through the region; and the whole neighborhood became excited, alarmed, and enraged. The wildest stories were told: 'She is going to be the missionary's wife for a week;' 'The amount to be paid the missionary will ruin the family.'"

Learning constantly from experience, Mackay eventually found an opening for Christianity:

"This ancestral feast on the last night of the year is to the Chinese what Passover night is to the pious Jew. It has been my custom never to denounce or revile what is so sacredly cherished, but rather to recognize whatever of truth or beauty there is in it, and to utilize it as an 'open sesame.' Many, many times, standing on the steps of a temple, after singing a hymn, have I repeated the fifth commandment, and the words 'Honor thy father and thy mother' never fail to secure respectful attention."

For the hundredth anniversary of Mackay's death, a delegation from his hometown in Canada accepted an invitation to participate in memorial activities in Taiwan. Here they stand in front of Mackay's tomb on the campus of Tamkang Junior High School. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

A free dental policy

Medicine was also one of Mackay's most useful opening gambits, for it was one of the easiest ways to earn gratitude and trust.

Mackay's medical work mostly involved treating malaria and pulling teeth.

Back then malaria was the most widespread and feared disease in Taiwan: "The most malignant disease, the one most common and most dreaded by the people, is, as has been suggested, malarial fever. It is not an uncommon thing in Formosa to find half the inhabitants of a town prostrated by malarial fever at once. I have used Podophyllum and Taraxacum in pill form at first, then frequent doses of quinine, followed, if necessary, by perchlorate of iron. A liquid diet, exercise, and fresh air are always insisted on."

The image of Mackay in people's minds is a man holding a Bible in one hand and a pair of dental forceps in the other. And he did write a fair amount about the state of dentistry in Taiwan:

"Toothache, resulting from severe malaria and from betel-nut chewing, cigar-smoking, and other filthy habits, is the abiding torment of tens of thousands of both Chinese and aborigines. The methods by which the natives extract teeth are both crude and cruel. Sometimes the offending tooth is pulled with a strong string, or pried out with the blade of a pair of scissors. The traveling doctor uses a pair of pincers or small tongs. Jaw-breaking, excessive hemorrhage, fainting, and even death frequently result from the barbarous treatment."

Having studied medicine in New York and Ontario, he quickly made designs for medical equipment that he had locals manufacture for him. Then he sent away to New York for a set of state-of-the-art instruments.

"Our usual custom in touring through the country is to take our stand in an open space, often on the stone steps of a temple, and, after singing a hymn or two, proceed to extract teeth, and then preach the message of the gospel. The sufferer usually stands while the operation is being performed, and the tooth, when removed, is laid on his hand. To keep the tooth would be to awaken suspicions regarding us in the Chinese mind. We have frequently extracted a hundred teeth in less than an hour."

In his life, how many teeth did Mackay pull? According to his own records, "I have myself, since 1873, extracted over 21,000, and the students and preachers have extracted nearly half that number."

The former Mackay family residence (top), Oxford College (middle) and the Mackay Memorial Hospital (bottom) are all well preserved. (photos by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Captain Mackay

Apart from traveling widely to pull people's teeth and to treat their malaria, Mackay also established northern Taiwan's earliest Western hospital and medical school.

Mackay opened his first "hospital" in 1873, inviting a Dr. Ringer who served the English business community in Tanshui to help him with the medical work. Mackay's disciples and the students at the Oxford College that he established all had to undergo medical training, so that they would be able to offer medical advice in the course of their work spreading the gospels.

In 1880 in Tanshui, Mackay established the first true Western medical facility in northern Taiwan: the Mackay Clinic. It was originally named not after him but after an American shipping captain from Detroit who was also named Mackay and whose wife had given US$3,000 to establish this hospital in honor of her recently departed husband.

Its operations were suspended for five years after Mackay died, until 1906 when the Canadian missionary doctor James Young Ferguson reopened it under the auspices of the Canadian Presbyterian Church with the name Mackay Memorial Hopital. This time its name was in honor of George Mackay himself, who after all had pioneered modern Western medicine in northern Taiwan.

Oxford College was started by Mackay with funds from people back home in Ontario. In 1880 Mackay returned to Canada for the first time, and people living in his home county of Oxford contributed US$6,000 for him to return to Taiwan and construct a school. The source of the money is why it was named Oxford College. In 1884 Mackay went a step farther to establish a women's college, which helped to shatter the widely held misconception of the time that women are intellectually inferior and shouldn't be educated.

Nevertheless, even before these schools were established, Mackay had already started an "outdoor education program." He wrote, "Our first college in North Formosa was not the handsome building that now overlooks the Tamsui River and bears the honored name of Oxford College, but out in the open under the spreading banian-tree, with God's blue sky as our vaulted roof."

The former Mackay family residence (top), Oxford College (middle) and the Mackay Memorial Hospital (bottom) are all well preserved. (photos by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

On the road again

Long periods traveling were a special characteristic of Mackay's missionary work in Taiwan. Wu Wen-hsiung, a Presbyterian minister in Kuantu, points out that Mackay spent months or even years at a time away from home. Few missionaries were as enamored of travel as he. Mackay criss-crossed Taiwan from Miaoli north, and eastward to Ilan and Hualien. His journeys brought him into contact with Han Chinese speakers of both Hokkien and Hakka, as well as aborigines of both the plains and mountains.

"There are many modes of traveling, the chief of which is traveling on foot. It is often dangerous and always wearisome. The paths are so rough-now over mountains, now across hot, blowing sands, now through jungle-and the mountain torrents, especially during the rainy season, are so numerous and difficult to cross."

The trips that Mackay took brought him even to Kueishan Island (which he called Steep Island), to which many Taiwanese haven't even gone today.

"Passage for myself and several of the students on board a junk loaded with planks was engaged from Tamsui. We set out, but the winds were contrary, and after two days of tossing and seasickness we rounded the northern point of Formosa and ran into Kim-pau-li, on the northeast. Here we got water and food, for our supply was well-nigh exhausted. Setting sail again, we were driven far out of our course, first eastward and then to the north. For five days and nights we were carried hither and thither by the merciless waves. On the fifth day, scarcely knowing where we were, having been driven back over our track, we sighted land. What was our delight when we found that we were on the lee side of Steep Island, and right grateful were we for the welcome of the islanders."

The Sino-French War was a dark period for Mackay's work as a missionary.

"In the summer of 1884 several French war-ships appeared, and very soon the news spread throughout North Formosa that the French were coming. The people were both alarmed and enraged. Their animosity was aroused against all foreigners and those associated with them. The missionary was at once suspected. A cloud hung over our entire mission work."

A mob destroyed the Talungtung Church, and they even went so far as to make a tombstone for Mackay, on which they wrote: "Mackay, the black-bearded foreigner, is buried here. His work is finished."

In October a British warship anchored itself in Tanshui harbor to protect the foreigners there. The ship's captain invited Mackay to come aboard with his wife and valuables. Mackay responded, "My valuables were in and around the college: The men who were my children in the Lord. They were my valuables! While they were on shore I would not go on board. If they were to suffer we would suffer together."

Later, Mackay received an order from the British to depart Tanshui for Hong Kong. He left his dependents in Hong Kong and then tried to return to Tanshui. But because Tanshui was closed, he was repeatedly denied entry. When he finally succeeded in coming on shore, he was welcomed by the Christian devotees, many of whom shed tears of joy.

On a trip from Tanshui to Ilan, George Mackay passed through Santiaolin. He established a total of 60 Presbyterian churches in Taiwan, including 34 in Ilan alone.

The sound of the flowers

Not only did Mackay speak Taiwanese and marry a Taiwanese woman; he also conducted research and left records about Taiwanese customs. In From Far Taiwan, he wrote, "I witnessed the execution of four soldiers condemned for burglary: One was on his knees, and in an instant the work was done. Three blows were required for the second. The head of the third was slowly sawed off with a long knife. The fourth was taken a quarter of a mile farther, and amid shouts and screams and many protestations of innocence he was subjected to torture and finally beheaded. The difference in the bribe made the difference in the execution."

"The pig is a great pet among the Chinese. It is always to be found about the door, and often has free access into the house. In our missionary journeys we frequently found ourselves room-mates of an old black pig with her litter of little ones."

In his home Mackay had a study where he kept his collection of stone carvings, building tools, weapons, clothes and implements used in all facets of aboriginal life. It was a small museum.

"The botany of Formosa presents a subject of intensest interest to the thoughtful student," Mackay wrote about another of his scholarly interests. "For the missionary there is a tongue in every leaf, a voice in every flower. Do we not, as the great naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, said, 'obtain a fuller and clearer insight into the course of nature, and increased confidence that the mighty maze of being we see everywhere around us is not without a plan?'"

In addition to conveying his love of nature, Mackay thought that this research was advantageous to his missionary work "in humbling the proud graduate, conciliating the haughty mandarin, and attracting the best and brightest of the officials, both native and foreign."

This Amis chief and tribesmen were good friends of Mackay.

A name known far and wide

Today there are 210,000 Presbyterians and 1,200 Presbyterian churches in Taiwan. These impressive numbers are due in large part to the work done by Mackay. In his 29 years as a missionary in Taiwan, he established 60 churches, each with its own minister. He also established a theological seminary, a girls' school, a hospital, and various other institutions. Mackay always encouraged locals to work at these institutions, but he was a strong leader not given to delegating responsibility. As a result, the local churches relied upon him to make all tough decisions, a situation that didn't change until he passed away.

How great was Mackay's contribution? From a poem that was published in a Japanese-era newspaper in Taiwan, you can see the respect he enjoyed among the people:

Facing the sea, back to the hills on a small city street/ I view the river winding in front of the house./ The Western wind blows culture toward the Land of the Rising Sun./ Everywhere people speak of a man named Mackay.

In 1995, Tanshui erected a bust of Mackay. Traces of his life are also seen in "Mackay Street," as well as in Aletheia Street, Tamkang Junior High School, and Aletheia University. What was "Oxford College" is now the campus history museum at Aletheia University. The Mackay Memorial Hospital still exists, and the old Mackay residence is now an international academic exchange center. Mackay left his imprint all over Tanshui.

In 1932 Taiwan's northern Presbyterian churches held a ceremony at the Tamkang Junior High School to mark the 60th anniversary of Mackay's arrival in Taiwan.

Picking up the torch

Last year Mackay's beloved Tanshui and his birthplace of Oxford, Ontario formally established sister-city ties.

June 2 of this year is the 100th anniversary of Mackay's passing away, and the Presbyterian Church is holding a series of events to call attention to Mackay's achievements.

This series of activities, which aim to honor Mackay's energetic spirit, his preference for "burning rather than rusting out," started in March. A delegation of 30 people from Oxford County, Ontario including government officials, a Scottish bagpipe group, and a women's tug-of-war team accepted an invitation to visit Taiwan for the Mackay Memorial Tug-of-War Championship and related activities.

Zorra township Mayor James Muterer only realized the impact of Mackay when he saw for himself the hospitals, church and schools. "He's been dead for so long, but everyone still misses him. He not only made a big impact on Christians; he also influenced non-Christians."

What's more, a music festival in Mackay's honor and a tour of Taiwan retracing Mackay's journeys as a missionary are also being planned. And stamps, videos and books related to Mackay are due out in coming months. In June Mackay's collection of aboriginal implements from the Toronto Museum is to be exhibited in Taiwan to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of his death.

Mackay took this photo of warriors in the garb they wore when hunting heads.

His final resting place

Mackay's love of Taiwan was amply expressed in From Far Taiwan, a memoir about his life on the island edited by his friend J. A. Macdonald. It begins: "Far Formosa is dear to my heart. On that island the best of my years have been spent. There the interest of my life has been centered. . . .

"I love its dark-skinned people-Chinese, Pepohoan, and savage-among whom I have gone these twenty-three years, preaching the gospel of Jesus. To serve them in the gospel I would gladly, a thousand times over, give up my life. . . There I hope to spend what remains of my life, and when my day of service is over I should like to find a resting-place within sound of its surf and under the shade of its waving bamboo."

In 1901 Mackay died from throat cancer at the age of only 57. He is buried in Tanshui, and not at the cemetery for foreigners.

After Mackay died, his son George William went back to Canada via Hong Kong. In 1911 he and his wife returned and opened the Tamkang Junior High School. He continued living there even after he retired. When he died in 1963, he was buried on campus in a tomb next to his father. Thus, Taiwan is his final resting place too.

Although Mackay's descendants do not now live in Taiwan, the Presbyterian Church still wanted to put on an impressive series of activities to remember him on the 100th anniversary of his death, in the hope that Taiwanese would be reminded about that period of the island's history. "Taiwanese lack a sense of history, and the history of the island itself has been marginalized," laments Luo Jung-kuang. "People with an understanding of history are more compassionate and humble. Only with a sense of history can a people find new direction and sense of purpose." Looking back on Mackay's life in Taiwan over a century ago tells us that with love this island can really become a place where people want to stay forever.

In Tanshui Mackay left behind more than just buildings and history; he also passed down a spirit of sacrifice and love for Taiwan and its people. The Presbyterian Church, which he helped to introduce in Taiwan, is now a major denomination here. Even 100 years after his death, Mackay is well remembered in Taiwan. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

The former Mackay family residence (top), Oxford College (middle) and the Mackay Memorial Hospital (bottom) are all well preserved. (photos by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

George Leslie Mackay's feelings for Taiwan ran long and deep. After his death, his son George William Mackay and his wife returned to Taiwan, where they worked as missionaries for more than 50 years. When the younger Mackay died, he was buried next to his father in Tanshui.

A plains aboriginal weaver.

Pulling teeth was one of Mackay's favorite opening gambits to gain the trust of the locals. He pulled some 21,000 teeth all told in his years in Taiwan.

The scenery of Nanfangao is like that of a traditional Chinese landscape painting, but Mackay came here mostly to spread the gospel among the local plains aborigines.

The Mackay Memorial Hospital, which was established in 1879, was the first Western medical facility in northern Taiwan. Mackay is standing in the doorway.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)