Voices from a Buried History- The Takasago Volunteers

Jackie Chen / photos A History of the Rule of the Colony of Taiwan / tr. by Christopher MacDonald

March 1999

Towards the end of the Japanese occu-pation, the aborigines of Taiwan found themselves forced into a vast conflict which engulfed the world. Several thousand of their finest sons perished during that war, on the sun-scorched islands of the Western Pacific.

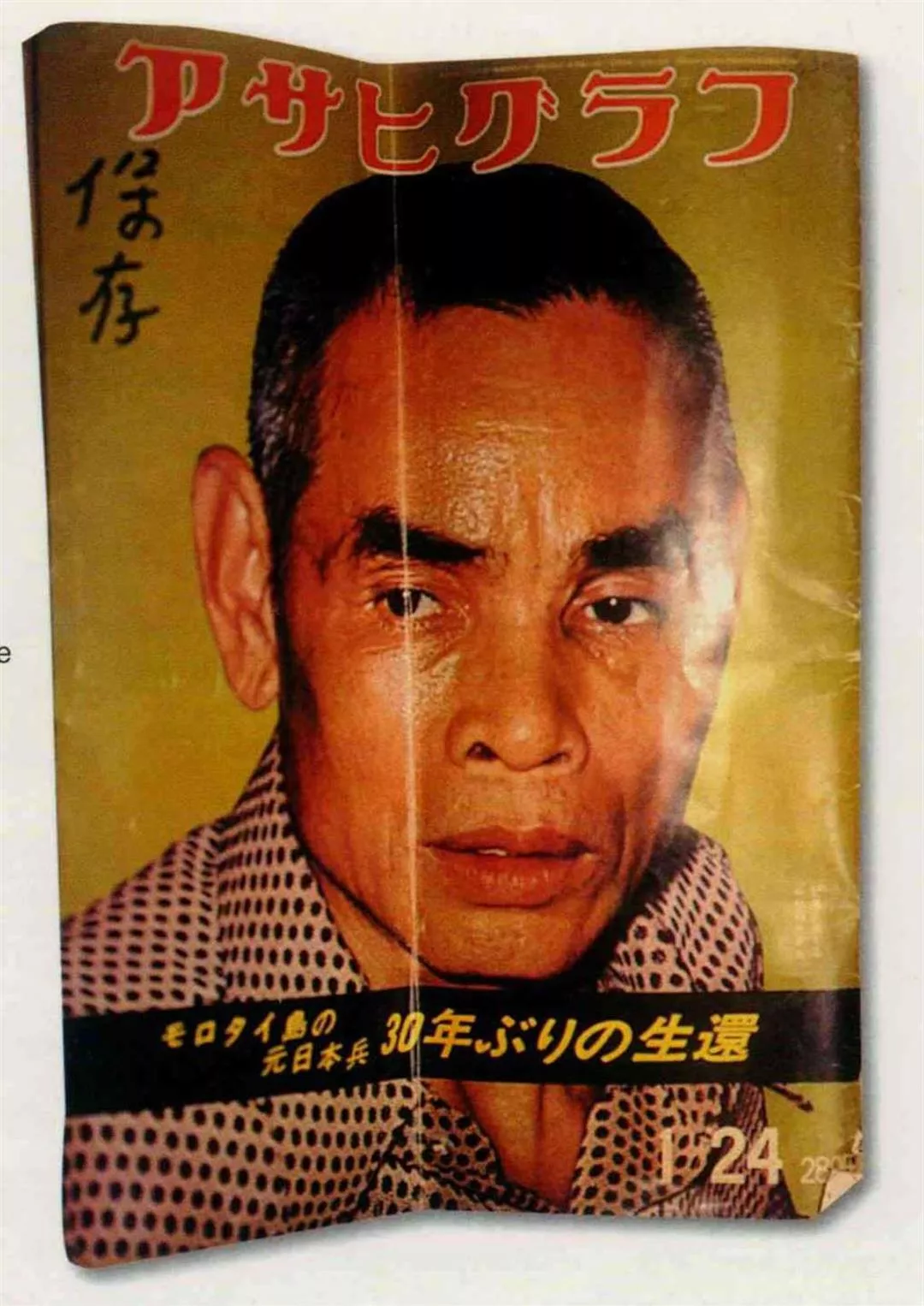

The 1974 discovery of a man in the Indonesian jungle, described as "the last Japanese soldier from WWⅡ to be found," made news around the world. The soldier was Ami tribesman Suniyon. (courtesy of Tai Kuo-hui)

This episode of history was seldom mentioned during the following three or four decades, whether in Japan, to which national loyalty was formerly pledged, or in Taiwan itself, now back in Chinese hands as part of the ROC. Then, in 1974, a surviving member of the Takasago Volunteers, Li Kuang-hui, emerged from the jungle on the island of Morotai, Indonesia. Later, through the investigative efforts of humanitarian researchers from Japan, along with numerous first-hand contributions from surviving Volunteers in Taiwan, a vague outline of this little-known story began to be pieced together.

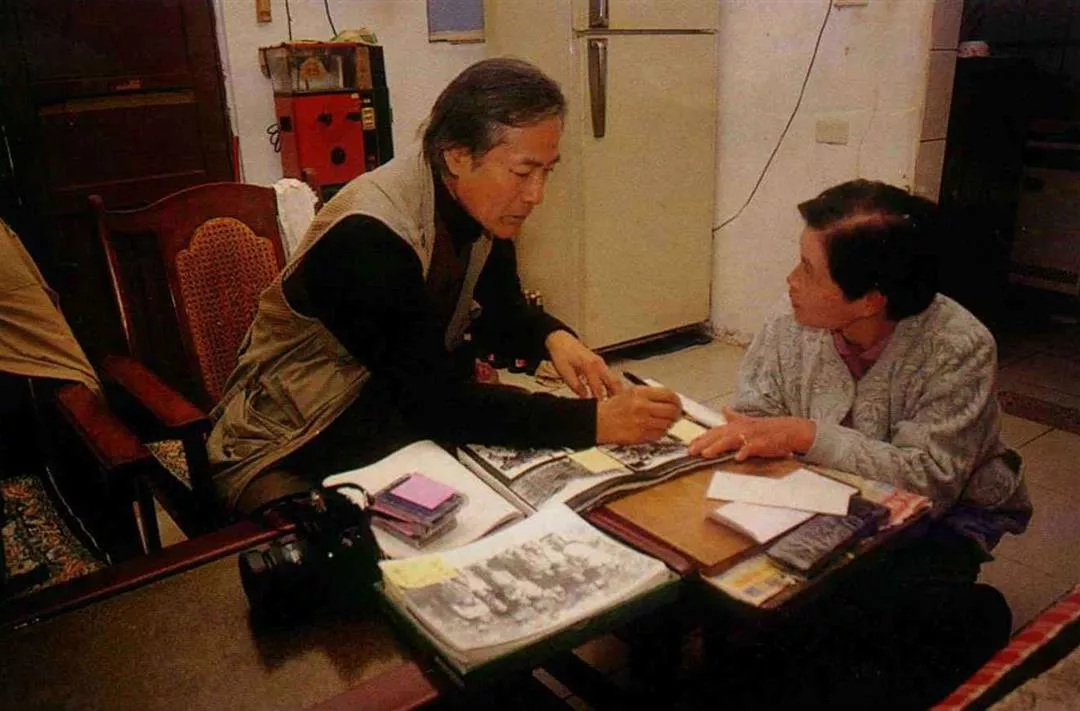

Japanese writer Hayashi Eidai is a humanitarian who is dedicated to carrying out field research on the Takasago Volunteers. Hayashi's father was tortured to death by Japanese police for his opposition to the war. This picture was taken at Wushe tribal community in Jenai Rural Township, Nantou County. (photo by Vincent Chang)

What do these events from the past mean for us today, at a time when voices around the world still clamor to make some sense of World War Two? How did the aborigines, who had no concept of "nation" prior to the Japanese colonial era, fare during this period, and what were their experiences? And how about the welter of emotions felt by veterans of the war, the surviving Takasago Volunteers?

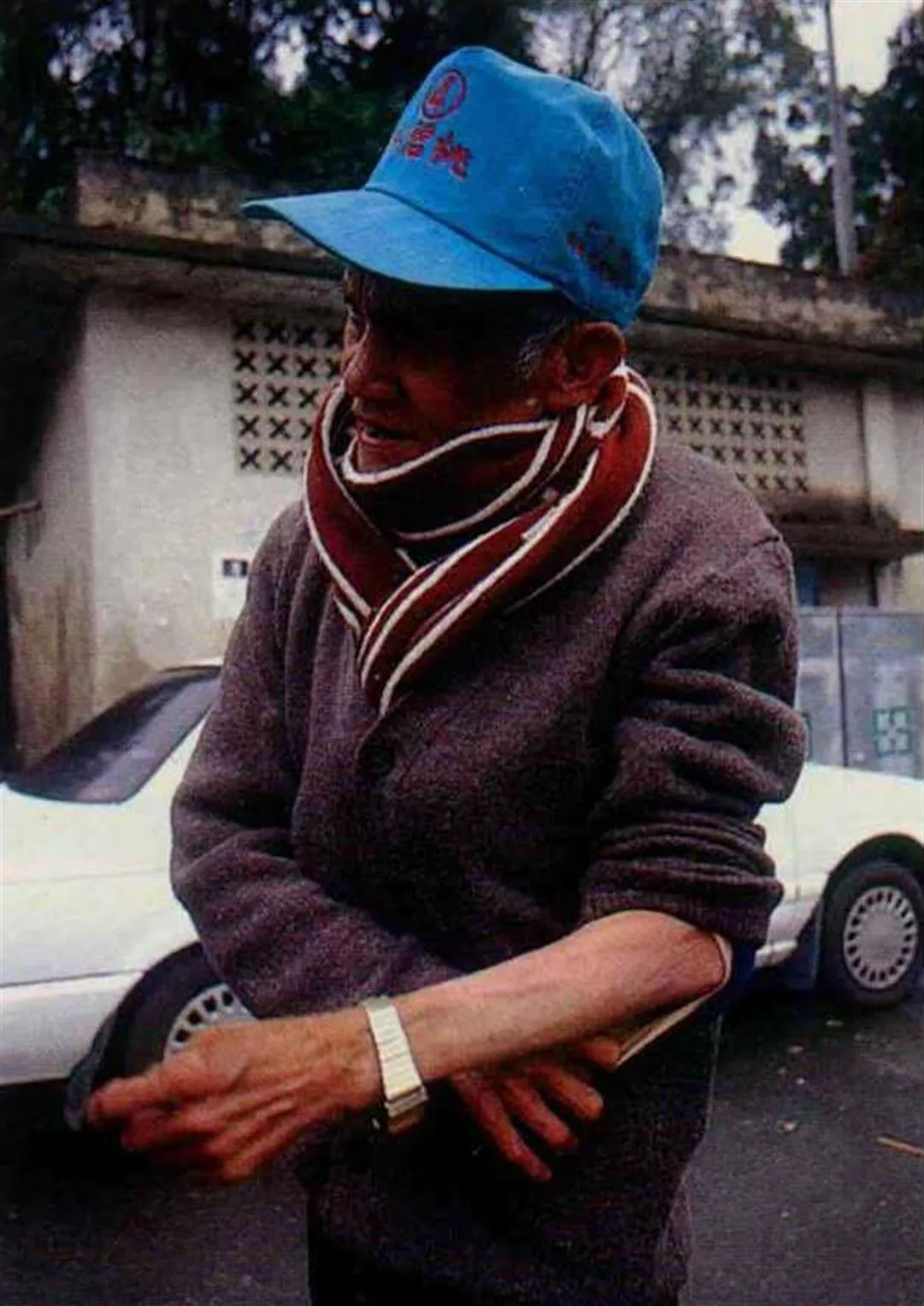

The injured arm protrudes from his rolled-up sleeve. There is a gnarled mass of bone at the elbow, above a forearm stripped of flesh-nothing but skin and bones, literally. It looks like a baseball bat. It was caught by an exploding shell, says the old gentleman, but he is no longer certain exactly where or how this happened.

The man who sustained this terrible injury is 77-year-old Atayal aborigine Lin Jen-chuan (Japanese name Morikawa Hitoshi), a member of the Lushan tribal community in Jenai Rural Township, Nantou County. Towards the end of the Second World War Lin joined the 3rd Takasago Volunteers, but after only four months' active service he was wounded, and left with a permanently maimed arm.

Men with similar stories can be found among aboriginal communities throughout Taiwan. Many more of those who went to war in the service of the Japanese emperor never made it back home again.

Lin Jen-chuan of the Lushan tribal community in Jenai Rural Township, Nantou County, whose arm was maimed four months after he went to war. (photo by Vincent Chang ) Right, Lin at the hospital in Tainan, when he was recovering from his injury. (courtesy of Lin Jen-chuan)

Takasago-the reformed "primitives"

Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 triggered war in the Pacific and drew Taiwan officially into WWII, the ravages of which reached not only the island's plains dwellers, but also the aboriginal tribes of the mountainous interior.

"'Takasago people' was a term coined by the Japanese government for Taiwan aborigines. The word 'takasago' comes from Japanese mythology, and was used to indicate that the former 'primitives' had become semi-civilized through being ruled and reformed by Japan." National Taiwan Chengchi University (NTCU) professor Fujii Shizu, from Japan, who has conducted years of research into Japan's "governing the barbarians" policy, explains that the Takasago Volunteers were considered the best of the tribal people, those most representative of the Japanese spirit, who "volunteered," under prodding from the Japanese police, to go to war for Japan.

Takasago veterans can be found among aboriginal communities throughout Taiwan, yet the historical episode of which they were a part has hitherto been glossed over. According to Sun Ta-chuan, vice chairman of the Council of Aboriginal Affairs: "The old folk won't talk about it, and the young don't know how to ask." In addition to the communication problem-the older people can only speak Japanese along with their native tribal languages-a further reason for the neglect of this episode is the fact that the war history of people in Taiwan has itself received little attention during recent decades.

As Huang Chih-hui, an assistant researcher at Academia Sinica's Institute of Ethnology points out, Japanese military authorities, aiming to avoid prosecution after the war, destroyed records of the bitterly-fought campaigns that took place in Asia and the Pacific from 1942 onwards, during which numerous atrocities occurred, along with cannibalism and other inhuman acts.

Furthermore, Takasago Volunteers were classed as military employees, who worked mostly as porters, and as laborers on the construction of airstrips, and took part in guerrilla actions in the jungle. They usually had no rank or formal military status, hence their absence from official war histories, not to mention the lack of veterans' organizations to bring them together and through which to develop a collective memory of events. According to Hayashi Eidai, a Japanese writer conducting field research into the Volunteers: "The Japanese government has never released the relevant documents in its possession."

From "Nakamura" to "Li Kuang-hui"

In December 1974, Ami tribesman Suniyon (Chinese name Li Kuang-hui) was discovered, like a ghost from the past, living on the Indonesian island of Morotai. After being cut off from "civilization" for over 30 years, he was found naked in the jungle, gathering firewood with his knife. In his bamboo hut he still had his army rifle and 18 rounds of ammunition, along with a canteen, an aluminum pan and a steel helmet. The miracle of his survival, alone in the jungle for three decades, astonished the world.

Suniyon's story reflects much of what has happened to the Taiwan aborigines during the past century. Under Japan's policy of enforced japanification as a means of controlling the aborigines, he had to change his name to "Nakamura Teruo," and then had it changed again by officials after Taiwan's return to Chinese rule-when "mountain brethren" began applying for household registration-to "Li Kuang-hui."

In 1943, when "Nakamura" departed for war from his home in Hualien, he was serving in Japan's Imperial Army, but after his long sojourn in the jungle he returned to a different world. Taiwan had undergone a "dynastic change," from being a Japanese colony to part of the ROC; his wife, assuming him killed in action, had remarried; his son, just one month old when his father went to war, was now a grown man of 30, waiting to meet him off the airplane. For anyone who recalls that era, the sight of "Li Kuang-hui" being greeted by his kinfolk at Sungshan Airport after years of separation, their hands linked in unique Ami fashion, remains an abiding image. And it was as a special volunteer, with the Takasago Volunteers, that Li was originally posted in 1943, the 18th year of the Showa reign, to fight for Japan in the Western Pacific.

For many people, Li Kuang-hui's emergence from the jungle stirred dim memories of the war, and of a slice of history that had long lain neglected. It also inspired several Japanese writers and journalists to unearth further information about the bloody sacrifices made by Taiwan aborigines in the war on behalf of the Japanese emperor, so lifting the lid on the hidden story of the Takasago Volunteers.

Japanese writer Hayashi Eidai, who studied at Waseda University, was one of those whose interest was aroused.

In the city of Kagoshima, Hayashi traced a former adjutant with the Volunteers, a Mr. Nakamura, and was able, with difficulty, to contact the man's wife. It turned out that her husband, who had once led a detatchment of Takasago Volunteers to New Guinea, had passed away the year before, but had left behind a register of members of the 5th Takasago Volunteers.

In recognition of the military exploits of 1st Volunteers, the Japanese Governor-General's Office erected a memorial in March 1944 (Showa 19), to those killed in action. The memorial is on North Tawu Mountain, a holy mountain for the Paiwan people. (photo courtesy of the Historical Research Commission of Taiwan Province)

A history to remember

Hayashi called on Mrs. Nakamura the following day, and was given a manual from the "27th Field Operations Supply Depot" (which is where the 5th Volunteers were stationed on arrival in New Guinea). There were nine volumes in total, listing names of men already demobilized, or killed in action, or alive and back in Japan, along with the location where the casualties fell, manner of death, next of kin and address in Taiwan. The registers were also packed with closely written statements of the sums that the troops held on deposit with the military postal authority, along with each man's seal and fingerprint. (Due to the difficulty of distributing wages during wartime, the Japanese established army post offices throughout the region, and credited wages to the soldiers' accounts. During the period of inflation and fiscal constraint that followed the war, Japan stopped accepting applications for the refund of these monies, triggering a wave of litigation against the authorities.)

As he delved deeper, Hayashi located several senior officers of the 5th Volunteers and traveled to Taiwan to talk with war survivors, collecting their accounts in his book The 5th Takasago Volunteers: Register of Names, Military Savings, Japanese Testimonies. Subsequently he visited tribal communities around Taiwan and interviewed surviving members of the Volunteers, resulting in the publication of Testimonies, as well as a volume of photography entitled A History of the Rule of the Colony of Taiwan. Together, Hayashi's three volumes constitute the most comprehensive collection of resources on the history of the Takasago Volunteers.

Huang Chih-hui notes that there are still a number of unresolved matters regarding the Takasago Volunteers. To her knowledge there are no more than ten works on the topic available in Japan, largely comprising oral accounts given by surviving officers and men, and there is, as yet, no systematic approach to the subject. There is even less Chinese-language research on the Volunteers, however, with nothing available other than a handful of first-hand accounts by veterans.

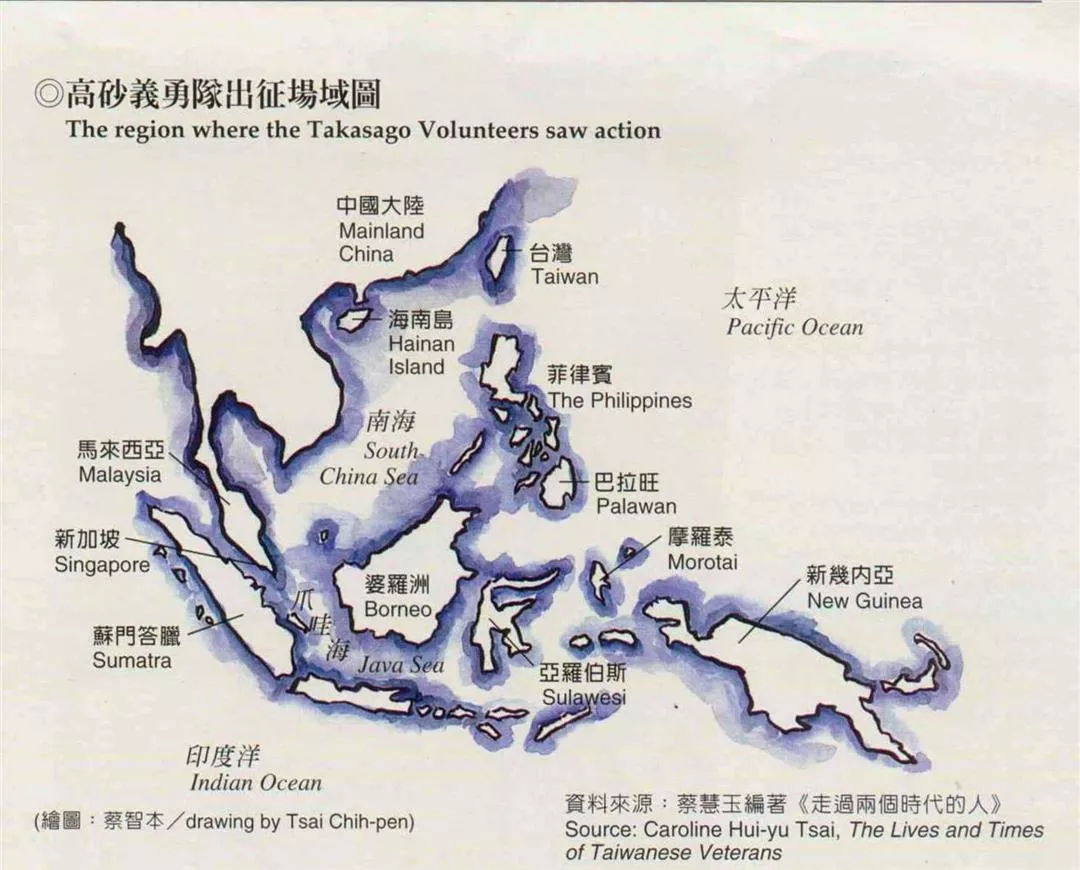

The story of the Takasago Volunteers that has been pieced together from the accounts of survivors and other historical documents is that the Governor-General's Office recruited eight separate corps of Taiwan aborigines, after the attack on Pearl Harbor and during the intensification of the conflict in the Pacific, and they were sent to fight between March 1942 and 1945.

While the 1st Volunteers fought mainly in the Philippines, the following six corps saw service in various parts of the Pacific and Asia, including British New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Rabaul and Morotai. As for the 8th Volunteers, some say that they were demobilized before they could ever be sent to the front, while others claim that they did in fact sail to Borneo before returning to Taiwan. In addition to the eight corps of Takasago Volunteers, there were also other volunteers serving in the army and navy.

According to research by Huang Chih-hui, a total of 7,000-8,000 men, at a conservative estimate, were recruited for the eight corps of Takasago Volunteers and other special volunteer services, the great majority of whom died in action. (However, Hayashi Eidai and others put the combined total for the eight corps at around 4,000 men, 30% of whom survived the war.)

At present, there are no conclusive figures for the numbers of men who died, or who remain alive to this day, and much is conjecture. Huang Chih-hui believes that this most fundamental of matters should be urgently investigated and clarified by the relevant departments.

The Wushe Incident is considered one the main reasons that the Japanese decided to recruit the Takasago Volunteers. At the time of the Incident, the Japanese deployed Atayals in a punitive action against the their own tribesmen, a tragic episode which Hayashi Eidai considers a perpetual source of pain for Atayal people.

Fight barbarians with barbarians

Why did the Japanese look to the aborigines, those on the lowest rung of Taiwanese society under Japanese occupation, as the war was expanding and entering its most critical phase, and send them to the front lines of Asia and the Pacific?

As Huang Chih-hui points out, the Japanese were early to recognize the fighting qualities of the Taiwan aborigines, with Lieutenant Nagano remarking on this fact during his inspection of mountain districts in 1895. But in the opinion of Hayashi Eidai, contemporary records indicate that it was the Wushe Incident, above all, that encouraged the Japanese to draft Taiwan aborigines for their armies.

In 1930, aborigines in the area of Wushe stormed a sports day at the local school, killing over 100 Japanese, including policemen and teachers. The motivation for the attack was anger at Japan's repressive policies for "governing the barbarians," by which the authorities endeavored to requisition territory and exploit the forestry resources of Taiwan's central highlands. Under these policies, the culture and traditional ways of life of aboriginal tribes were effectively outlawed, and those that resisted were massacred. The Japanese responded to the Wushe killings with massive force, bombarding the aborigines' mountain stronghold from the air, though without managing to subdue them. Finally the Japanese opted to "fight barbarians with barbarians," using inducements to recruit Atayals from another district, who attacked and defeated the defiant tribesmen.

After the Wushe Incident, the Japanese had a high regard for the aborigines' combat skills in the forested mountains. As Hayashi points out, one officer with the punitive expedition recorded the following comment about the aborigines in his notes: "Their ferocity is truly repugnant, but if they could be guided towards civilized ways, then maybe, in an emergency, they could under our leadership become part of the army." Following the Wushe Incident, the Japanese clearly began to regard the aborigines as a potent reserve force.

Another factor was that in the wake of Pearl Harbor, there were only limited numbers of fit, potential conscripts left in Japan, and with the expansion of the Japanese lines from the Pacific to Southeast Asia, the tough, hardworking aboriginal youths, with their knack for fighting in forested mountain terrain, naturally became a priority consideration.

A crucial element in the establishment of the Takasago Volunteers for combat in Southeast Asia was the fact that Lieutenant-General Honma Masaharu was commanding officer of the Taiwan region at the time. Known as an enlightened man, Honma also commanded the invasion of the Philippines. As professor Tai Kuo-hui of NTCU explains: "When Honma was fighting desperately in the Philippines, he thought of the remarkable abilities of the Volunteers, able to "run barefoot through the mountain jungles, and pierce the night with the power of their eyes."

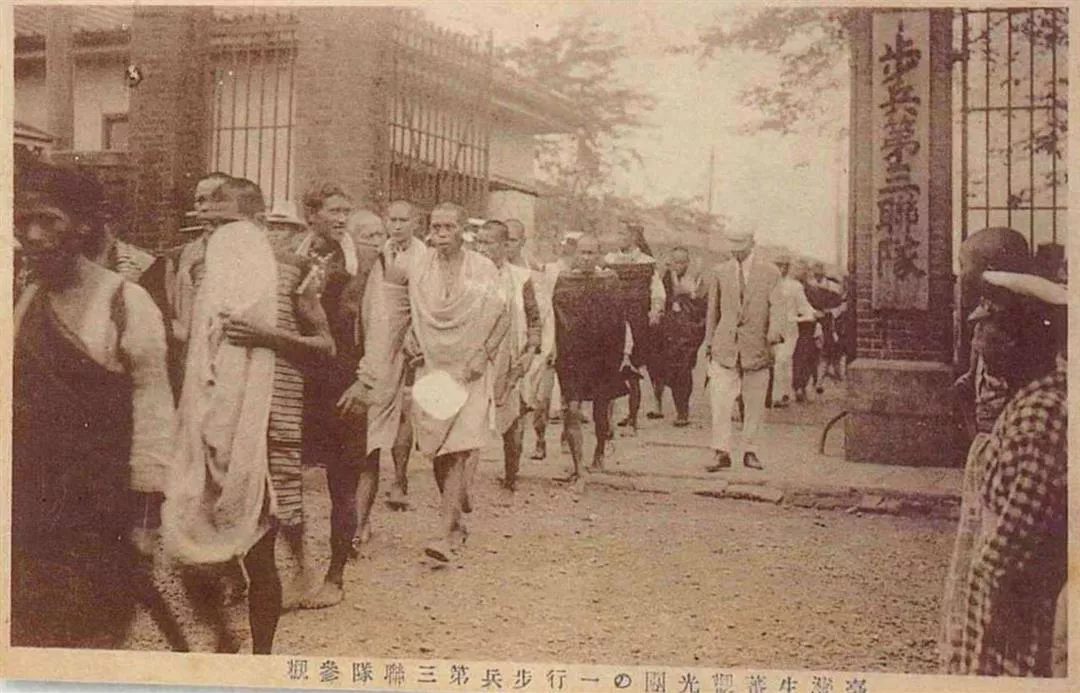

The Japanese monitored and controlled the aborigines through their police network, but they also used "conciliatory" methods, providing them with education and arranging trips to Japan. This postcard shows "A Visit to the 3rd School of the Japanese Infantry by the Taiwanese Natives Sightseeing Group." (courtesy of Lin H an-chang)

If you don't join up, you're not a man

In a Japanese wartime propaganda film, young aborigines who have been studying away from home, return and eagerly wait to be recruited. Those who receive the call-up are jubilant, while those who don't are shattered by the disappointment. Allowing for some exaggeration, the film gives a fair reflection of the mood of enthusiasm for the war that had been whipped up among recruits at the time.

Says 78-year-old Bunun tribal and Wushe resident Kao Tsung-yi (Japanese name Kato Naokazu): "It was as natural then for a young man to be asked 'when do you join up?' as it is for someone today to say 'have you eaten yet?'" At that time, everyone thought it an honor to become a soldier, and was ready to die in the war. Kao wrote his "blood letter," a mark of determination, in July 1943, and joined the 7th Takasago Volunteers.

In a documentary by Japanese film-maker Yanagimoto Michihiko, an old aboriginal lady from Shoufeng village in Hualien is interviewed about her personal recollections. She describes how anxious her husband was to join the army, just 14 days after the birth of their son. "My husband said all his friends had joined up, so how could he not go too? He said: 'If you're not a soldier, then you're not a man.'"

The Japanese had two ways of enticing the guileless aborigines to join up. For one, they offered high wages. Yang Ching-ke (Hirayama Isamu) of Taiwu Rural Township in Pingtung County, a veteran of the 5th Volunteers, recalls that a monthly wage of 80 yen was promised-a highly attractive sum to people who in those days had little experience of working in return for money. Secondly, the Japanese employed a form of psychological persuasion. "They had a dual approach," explains Hayashi Eidai, "on the one hand teaching the girls to think that 'anyone who doesn't join the Takasago Volunteers isn't a man,' while at the same time telling the guys that according to the girls, anyone who doesn't join up isn't a man."

Judging by the recollections of the survivors, whatever fears the new recruits may have felt were swamped in the mood of "collective madness," and by the general fervor for war on behalf of "the country." Some joined the army in such haste that "they left without even having a chance to say good-bye to their families," according to former Volunteer Liu Te-lu (Takeyama Katsuo), an Atayal from Kuanhsi in Hsinchu. Others underwent a short training course in Taiwan or the Philippines before being sent to join the war.

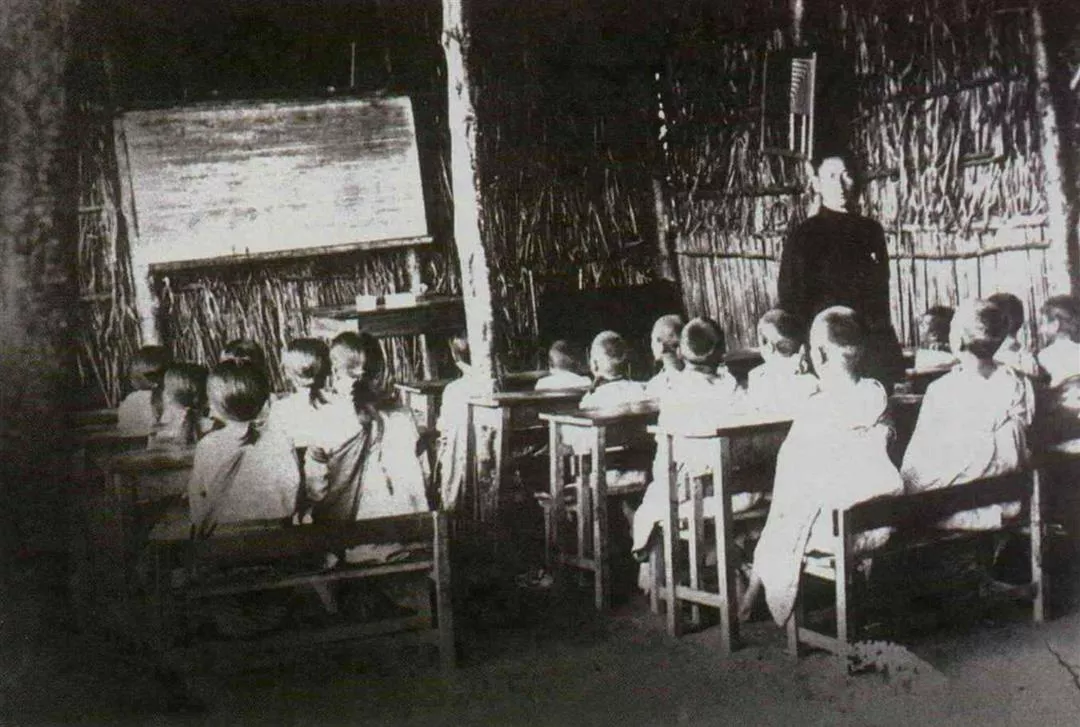

Colonial police officers doubled as schoolteachers, educated the aborigines about agriculture and sanitation, and even provided medical services. This picture from 19 32 shows a class at the Ma-li-pa School for Aboriginal Children, with their teacher, Officer Yoshimi.

No roads in the jungle

Although not recorded in official histories, descriptions of the Volunteers found in the notebooks of Japanese war veterans often exude an air of wonderment.

"The Takasago Volunteers were youngsters who seemed to have been born for guerrilla combat, especially when they launched an attack on an enemy camp. Their instincts and intuition amazed even those of us who were graduates of the Nakano School." (The Nakano School was a secret institution established during the war to train military espionage operatives. Students were selected from among Japanese officers and men, and received rigorous instruction in espionage and intelligence techniques.)-Excerpt from the oral testimony of 18th Army staff officer Nariai Masaharu, collated by Hayashi Eidai.

"They shuttled back and forth in the jungle, where there were no roads, gathering intelligence about the enemy. They could pick out sounds over great distances, and were able to lure the enemy into position, exactly according to instructions. They took guerrilla warfare to its extreme of ingenuity, and were a driving force that gave our side the edge.

"They were also expert hunters, able to catch boars, pheasants, and lynxes, as well as snakes, shrimp, eels, frogs and insects. They knew which parts were edible and which were not, saving us from starving in the mountains where we lacked provisions, and teaching us the basics of daily life under such conditions. When we had malarial fever they risked danger to bring coconut milk from the coast, and they also looked after us when we were weak with malnutrition." (From The Chuntao War Chronicles, compiled by the Morotai Veterans Association.)

The typical impression of the Takasago Volunteers that emerges from descriptions by the Japanese veterans is of men who were valiant, obedient, dedicated to their officers, and willing to lay down their own lives.

But in contrast to the reminiscences of the Japanese veterans, there is a heavy undertone of grief in the accounts given by ex-Volunteers themselves.

"We left Palawan aboard a freighter, fully laden with provisions and ammunition, sailing for New Guinea. On the third morning we were bombed from the air, and the entire mess crew was wiped out at a stroke. . . .

"During the retreat the Volunteers carried heavy loads of provisions. The route was lined with exhausted troops who were falling behind, staggering on their feet, looking wrecked, suffering from dysentery, malaria. . . . Some soldiers were so worn out that when they squatted to drink from a mountain stream they couldn't get up again. To avoid lighting fires that might be spotted by Allied aircraft, we often had to gnaw on uncooked rice to stave off hunger." (Oral account of Yang Ching-ke, Japanese name Hirayama Isamu, of the 5th Volunteers, collected by the Historical Research Commission of Taiwan Province.)

The japanification of Taiwan's people targeted aboriginal people as well as plains dwellers. Pictured here with his family is Officer Ishida, an aborigine from Ku-la-ssu.

Conflicting emotions

Tai Kuo-hui points out that in their reminiscences, the Japanese always portray the Volunteers as paragons of obedience to Japan. But in fact, the truth was somewhat different.

Hayashi Eidai learned from Mrs. Nakamura that two days after the defeat of Japan her husband, an adjutant with the 5th Takasago Volunteers, told her to take their three-year-old and get away from the house. A few days afterward the guard on duty at the house was killed, and his decapitated corpse was later found in Taichung.

Ueno Tamotsu, an officer with the 5th Volunteers, says that he was almost thrown overboard during the voyage back to Taiwan at the end of the war. Years later, his son suggested that he visit Taiwan again, but Ueno always demurred, fearing retribution from former Takasago Volunteers.

Sun Ta-chuan points out that the aborigines' feelings towards their Japanese rulers were certainly mixed-a "love-hate complex." Under Japan's 50-year policy for "governing the barbarians," aborigines were looked down on and placed at the bottom of the social heap. Their very identity "was a form of indignity."

"The Japanese came first," explains Ami aborigine Cheng-Wang Chin-tsung of Taitung, "and the pailang (Han Chinese in the Ami language) second, while the aborigines were third-class citizens." As Sun Ta-chuan says: "In such circumstances, aborigines invariably felt themselves inferior when they encountered a Japanese person."

With this kind of mentality, and faced with the prospect of going to war and maybe sacrificing one's life, the reaction of the aborigines was, as described by Tai Kuo-hui, a determination to join up as soon as possible, so as to "erase the stigma." On the other hand, towards the end of the war, having witnessed the inhumanity of the conflict and the senselessness of the Japanese spirit, many aborigines began to doubt themselves, and wondered "just who they were fighting for."

Liu Te-lu of the 3rd Volunteers says that it was not until he was recuperating that he began to have doubts about the war, which have lasted to this day. He recalls how, before retreating and without any explanation, the Japanese slaughtered all the local tribespeople who had previously helped them. "They're really ruthless, the Japanese," says Liu.

Hayashi Eidai says, of the Volunteers: "Don't be distracted by their seemingly pro-Japanese public appearance, sometimes dressed in Japanese uniforms, with Japanese caps, and singing Japanese army songs. As soon as they had a drink it was not at all unknown for them to start cursing the Japanese for being heartless and immoral, and damning Japanese imperialism." Clearly, the Volunteers carry heavy psychological baggage from the war.

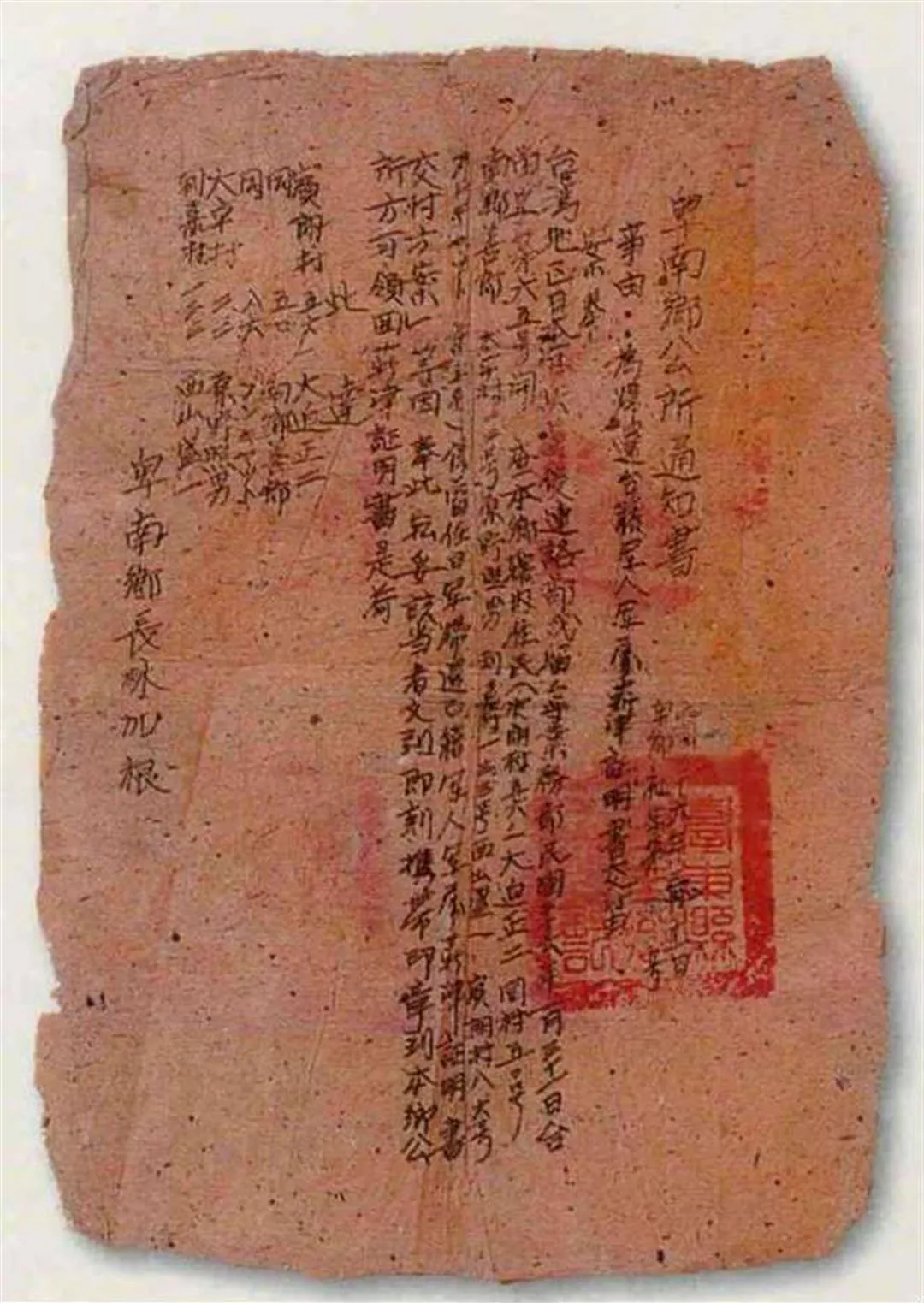

Notification from the administrative office of Peinan Rural Township, telling Takasago Volunteers to collect their wages. Japanese authorities stopped paying the Volunteers money that they were owed in wages, postal savings and military vouchers after the war, triggering a wave of litigation against the government. (courtesy of Sun Te-chih)

The psychology of terror

Worst afflicted were the young aborigines who grew up in the shadow of the Wushe Incident. Tai Kuo-hui explains that after that incident, virtually all male Atayals over the age of 15 and involved in the "uprising," were wiped out. Many of their children were ordered to move to Chingliu near Wushe. According to statistics gathered by Hayashi, some 33 young men from the Chingliu district joined the Volunteer Corps. As children, they would have seen their elders killed under the Japanese bombarment. "Could it be that their terror of the Japanese, and a feeling that they were doomed anyway, made them willingly ingratiate themselves with the Japanese police and become loyal servants of Japan?" asks Tai. This is a common type of psychology among victims of severe oppression.

Many Takasago Volunteers who survived the cataclysm of the war returned to live under a "new dynasty," the ROC, and found that their formerly Japanese-speaking world had suddenly become a Mandarin one. The language of the broadcast media had changed overnight, along with the dominant ideology. As time went by, their children and grandchildren grew up under the educational system of the nationalist government, completely different from the system during the Japanese era, and the ex-Volunteers became a lonely, lost group.

Some chose to shut themselves away, inhabiting a world of the past, at one remove from real life. Sun Ta-chuan had an uncle to whom this happened. "My uncle was originally an optimistic, cheerful type, but after Taiwan's reversion to Chinese rule he became uncommunicative. He listened to Japanese radio programs and watched Japanese television shows, and became totally immersed in his farming, cutting himself off from the outside world."

Takasago Volunteer recruits were usually the fittest, most capable young men of their tribe. Some, because of their uncommon experience of the war, strove to learn Mandarin on their return and eventually became leading figures in their own communities. "Many became county councilors, township magistrates and township representatives," says Sun. 7th Volunteers veteran Kao Tsung-yi, who is committed to obtaining compensation for Taiwanese who fought in Japan's armies, has for many years served as magistrate of Jenai Rural Township in Nantou County, and been a Nantou County councilor, while 3rd Volunteers veteran Liu Te-lu has served several terms as member of Hsinchu County Council.

Japanese boot camp in Southeast Asia, where recruits were trained round the clock.

Bringing back justice

During the 1990's, Taiwanese history began to undergo a "re-shaping" process, during which long-buried episodes started being considered afresh. After half a century of silence, members of the Takasago Volunteers also began to speak out. But it was the return of Li Kuang-hui from the jungle in 1974, that first brought the issue of compensation for Taiwanese veterans of Japan's armies to public attention.

According to Fujii Shizu: "By compensating Li Kuang-hui for his 30-year status as a Japanese soldier, the Japanese government reversed their own stand on not paying war reparations to individuals." In 1975, an organization of Taiwanese veterans of Japan's armies was formed, and from 1977 to 1987 it pursued the Japanese government through the courts, charging it with the "inhumanity" of differentiating between aboriginal Volunteers and ethnic Japanese soldiers in terms of the scale of compensation offered. Although the case was rejected three times by the high court in Japan, there are still individuals involved in Sino-Japanese exchanges who do not accept this and intend to continue pressing their case with the Japanese government. (The level of compensation available for ex-Volunteers is at present assessed as follows: the total amount of savings, wages, annuities and insurance contributions owed to Taiwanese-Japanese soldiers at the end of the war, termed the "confirmed arrears," can be reimbursed in a lump sum, at the rate of 120 times the original value-far lower than the multiple of 7,000 calculated by the veterans. For Volunteers who were killed or seriously wounded the compensation is *2 million, which is dwarfed by the sum of at least *40 million available for ethnic Japanese casualties.)

For many people, it is source of anger and pain to look back after 50 years, especially now that they know the vast disparity between the Japanese government's treatment of its Taiwanese and Japanese war veterans.

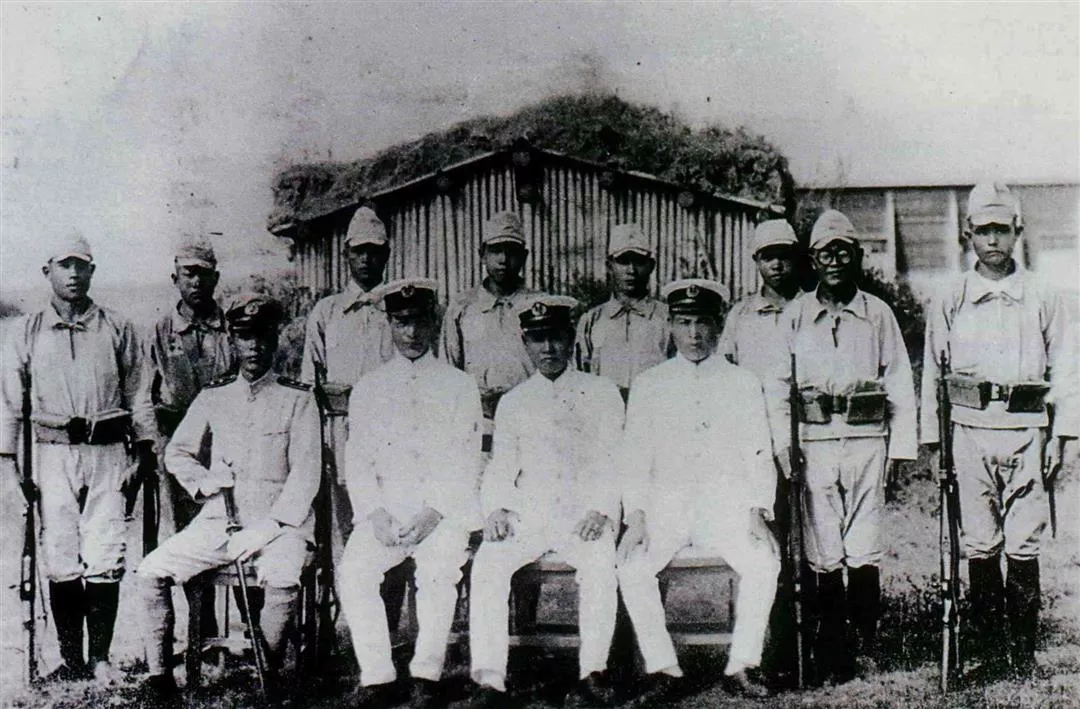

The 7th Volunteers--marines--training at Chuehnei, in Taichung, shortly before setting out for New Guinea. Kao Tsung-yi, wearing glasses and standing second from the right, is a Bunun tribesman from Wushe who also worked at the Taiwan Governor-General's Office under the Japanese, and later studied agriculture in Taipei. Nowadays he is a frequent spokesman for the Takasago Volunteers.

Banzai!

"It was for Japan that we went to war, and it was 'Long live the emperor!' that we shouted as we charged and fell on the battlefield. No-one was shouting 'Long live Chiang Kai-shek!'" says one veteran interviewed in Yanagimoto Michihiko's documentary film. "Our Japanese schoolbooks taught us that honoring one's commitments was the greatest of virtues, but the Japanese betrayed their obligations to us," says another former Volunteer from Shoufeng village in Hualien.

Once forgotten by history, then rediscovered after a 50-year hiatus, these men still face the same "separate treatment" as before. Sun Ta-chuan regards this as a cruel irony of history, as well as a great disrespect to the old veterans themselves. "What we want now," he says, "is first of all to get this history clear and look it together with the old gentlemen, from their perspective. At the very least we can provide emotional support, not just ignore their concerns and leave them to slip quietly from sight, as in the past."

The Council of Aboriginal Affairs has also called on the Japanese government to provide some form of compensation, be it spiritual or material, for these old veterans, once so loyally committed to serving Japan, as well as for the families of those who died. "It's not simply about paying back money. The important thing is that there is an acknowledgment and affirmation of what we did," says ex-Volunteer Kao Tsung-yi.

The Council of Aboriginal Affairs, along with non-governmental groups involved in Sino-Japanese exchanges that support the position of the veterans, believe that the issue of compensation and reparation still awaits further consultations with the Japanese government. Also, with the passing away of the old Takasago Volunteers, the Council of Aboriginal Affairs has proposed that the Japanese government could provide their descendants with scholarships for study in Japan.

Among other plans that are taking shape, the Council has proposed a delegation traveling to Southeast Asia for a ceremony at one of the battlegrounds where Takasago Volunteers were killed in numbers, to finally lay their souls to rest.

War is merciless. Ultimately, it is how later generations deal with the scars of history that determines whether or not those scars ever fade away.

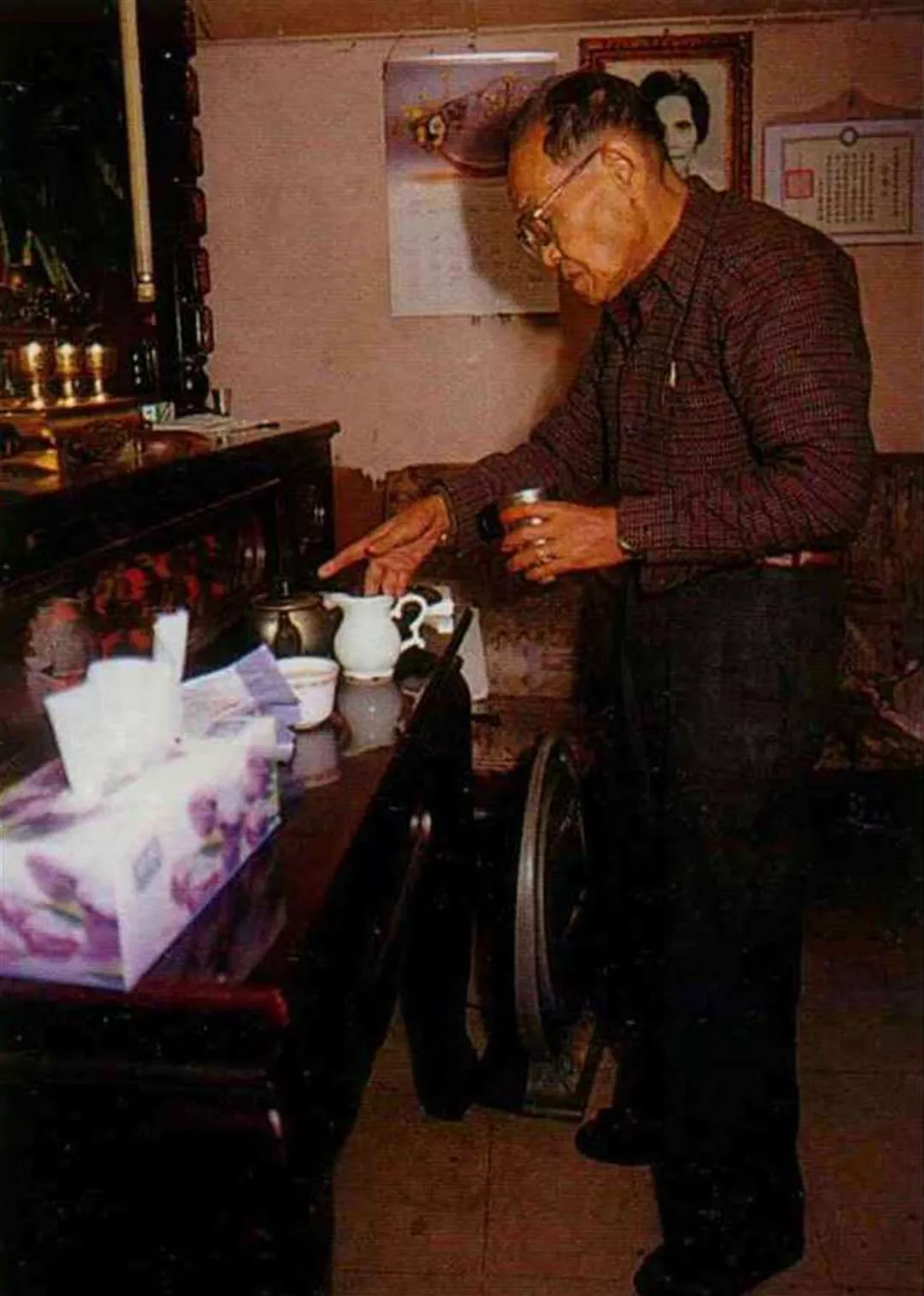

Now getting on in years, war veteran Kao Tsung-yi lives among his descendants in his hometown of Wushe. What aspirations does he still have as he enjoys his twilight years? (photo by Vincent Chang)

The graves of two fallen men of the 3rd Takasago Volunteers, in Yiwan, Taitung. The remains were brought home for burial by their comrade Chu Tu-yi (Nakano Mitsuo), who frequently visits the site and is shown here performing a Shinto ritual to pay his respects.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)