Indigenous Peoples in the Pages of Taiwan Panorama

Joanna Wang / photos by Jimmy Lin / tr. by Phil Newell

December 2025

MOFA file photo

Over the last 50 years, Taiwan Panorama has continually followed issues related to Indigenous peoples, publishing more than 250 reports. We have witnessed the transition of these Aboriginal peoples from being “part of the landscape” to their self-aware “subjectivity” and their refraction of changing values and perspectives in Taiwan’s society.

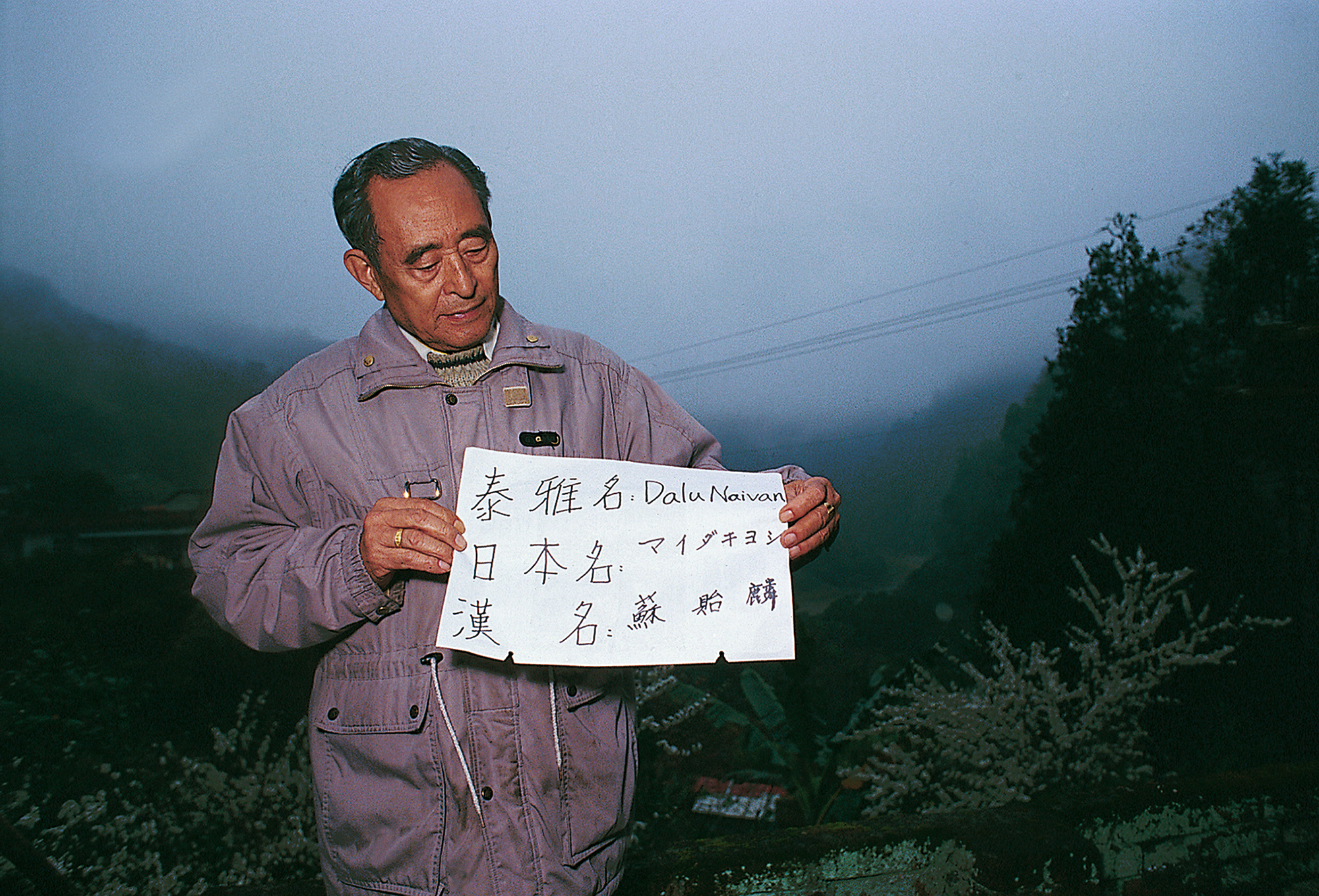

A movement to enable Indigenous people to use their traditional names on their ID cards culminated in 1995 amendments to the Name Act to allow this practice. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Indigenous activism experienced a “golden decade” after 1986, when movements to win more rights, use traditional names, and reclaim lands evolved. (MOFA file photo)

From scenic postcards to on-site reportage

In the 1970s, when Taiwan first began modernizing, Taiwan Panorama’s articles on Indigenous peoples mainly focused on their “beautiful scenery” and “folk customs,” or the use of photographs and cultural artifacts to show them as part of Taiwan’s rich heritage. A photo of two women in traditional tribal dress in the February 1976 article “Scenery of Wulai” was the earliest appearance of Indigenous peoples in our magazine.

In the 1980s Taiwan Panorama began visiting Indigenous communities to report on rituals such as the harvest festival of the Tsou people and the Saisiyat “Ritual to the Spirits of the Short People” (Pas-ta’ai). In 1986 we launched a series of articles on Aboriginal peoples, using on-site reporting and the analysis of scholars to examine the lives of these peoples from geographic, environmental, historical, and cultural perspectives.

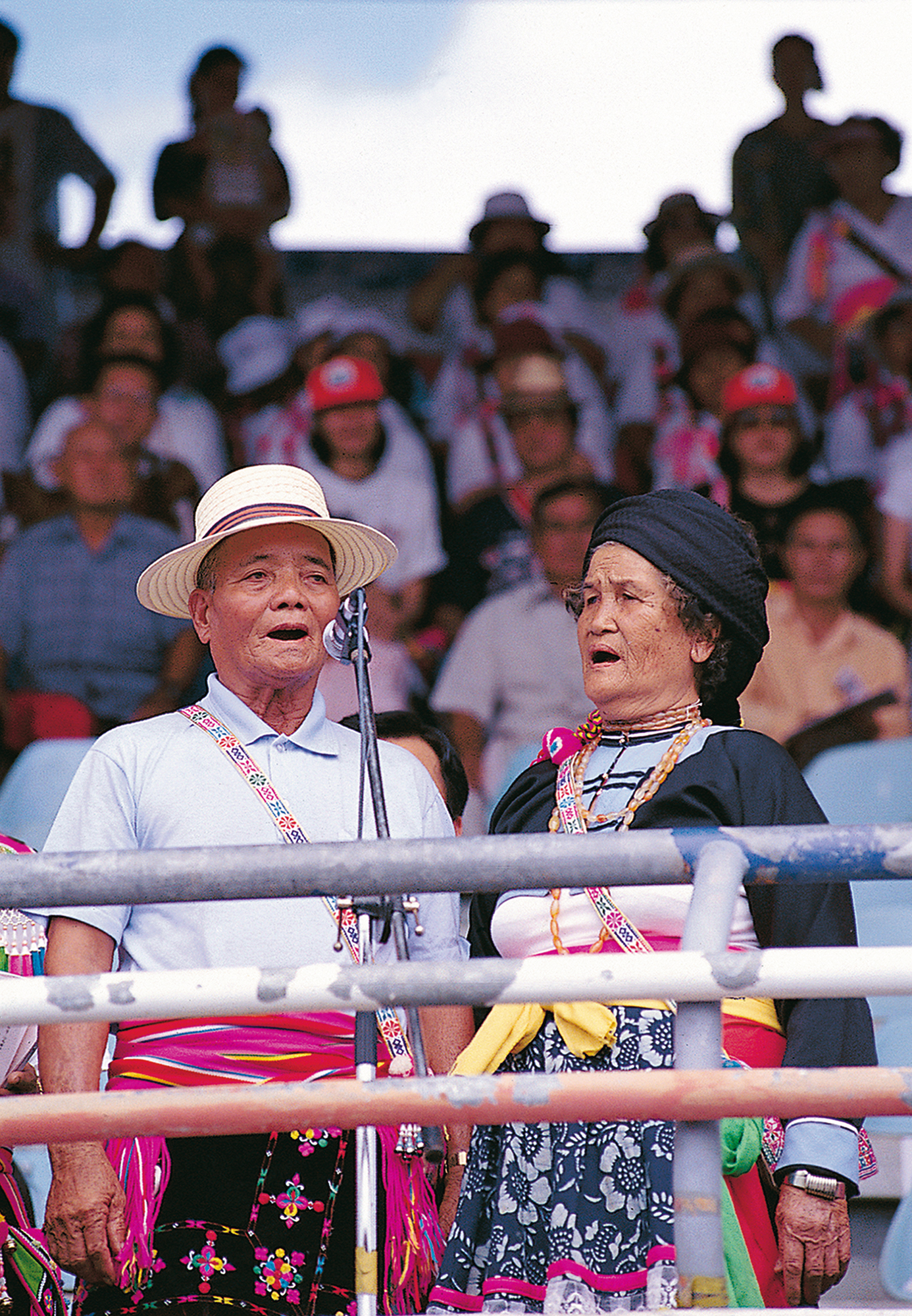

In 1996 a recording of the Amis Indigenous singers Difang and his wife Igay crooning “Elders’ Drinking Song” was incorporated into the anthem for the Atlanta Olympics, sparking a controversy over intellectual property rights. (MOFA file photo)

In 2009, Typhoon Morakot brought devastation to Indigenous communities and forced many residents to relocate away from their homes.

Following Typhoon Morakot, the path to reconstruction was long and tortuous. (photo by Kent Chuang)

Awakening: Subjectivity and rights

As Taiwan democratized and society mobilized, an Indigenous peoples’ movement also arose, and Taiwan Panorama began focusing more on individual figures and their life stories. In February of 1987 we carried a story about Tulbus Tanapima’s eponymous novel, which metaphorically presented the struggle of the Bunun Indigenous people between modernity and tradition and was the first example of Aboriginal literature to appear in the pages of Taiwan Panorama. In the 1990s, we introduced the Formosa Indigenous Song and Dance Troupe and the essays of the Atayal writer Walis Nokan, enabling Taiwan’s earliest inhabitants to convey their cultural experiences from a personal point of view.

The United Nations proclaimed 1993 as the first International Year of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, and in that year Taiwan Panorama carried a Cover Story entitled “Reawakening the Tribal Spirit,” showing concern for the lives of urban-dwelling Indigenous people and the trend among them of returning to their hometowns to revitalize them. The August 1996 Cover Story “Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights” explored how the use of recordings of the voices of the Amis Indigenous couple Difang and Igay in the anthem for the Atlanta Olympics sparked a controversy over intellectual property rights.

Meanwhile, the series of reports including “As My Grandpa Would Have Put It... Indigenous People Regain Their Names” and “Saving the Mountains and a Way of Life” recorded the struggle of Indigenous peoples in the political and human rights realms to reclaim use of their traditional names, rectify the names of their tribes, and restore hunting culture, reflecting a resurgence of identity and cultural consciousness. “Indigenous Reporters: That’s News to Me,” published in November 1994, told the story of a training course for Aboriginal reporters offered by Taiwan’s Public Television Service to “put the cameras and microphones in the hands of Indigenous people” in order to uphold their right to be heard in the media.

In the wake of the street action and shouted slogans of the Indigenous peoples’ movement, Taiwan Panorama published in-depth case studies of revitalization in Aboriginal villages and followed in the tracks of young Indigenous activists returning home to work on behalf of their communities. We reported on how a new generation of young Indigenous people were seeking a balance between modernity and tradition and rebuilding the links between themselves and the land.

Following the passage of the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law in 2005, an article titled “From the Streets to the Villages—The Indigenous Peoples’ Movement Turns 20” looked back at the movement’s achievements over the previous two decades. It noted that of all the gains, “the restoration of Taiwanese Aborigines’ self-confidence surely belongs at the top of the list.”

Around 2000, Indigenous performers were making a splash on the pop music scene, using music to transmit their culture. The photo shows the Puyuma singer Paudull.

Residents of Namaxia Township who returned home after Typhoon Morakot learned to smile once again.

Would the Rukai communities forced from their homes by Typhoon Morakot be able to set down roots in their new locations? Only time would tell.

The survival of the culture of the Tao people of Lanyu (Orchid Island) has depended on reestablishing links with the sea. (MOFA file photo)

Drifting, relocation, and reconstruction

Most Indigenous peoples’ communities are located in areas with unstable geology or limited land rights, and many of their residents have had no choice but to opt for drifting and relocation. “When Half a Village Moves” and “Village Relocations—Who Calls the Shots?” traced relocations of villages from the era of Japanese rule to the Jiji Earthquake of September 21, 1999 and Typhoon Mindulle in 2004. Later, “Vagabonds under the Bridge—The Story of Sanying’s ‘Urban Aborigines’” depicted the reality of the drifting and relocation of Amis urban dwellers who left Sanying Indigenous community to try to make a living in the city.

After Typhoon Morakot devastated Indigenous mountain communities in 2009, Taiwan Panorama published reports including “A Long Road to Walk—Rebuilding Namasiya” and “Strength in Solidarity: The Relocation of the Rukai of Wutai” as part of long-term tracking of the reconstruction process. We analyzed the difficult choices for Aboriginal people under the proposed principles of “Don’t abandon the hometown, don’t let the culture die out, keep the Rukai going on a sustainable basis.”

We later revisited affected Paiwan and Rukai communities to understand how they have built cohesion and revitalized themselves economically and socially.

The energizing effect of the younger generation is transforming Indigenous communities.

To recover disappearing traditional culture, the new generation began learning the old dances and songs from their tribal elders.to)

Links: From Taiwan to Austronesia

The November 2020 issue explored innovation and tradition in Indigenous culture. Also, at one of our “New Southbound Cultural Salon” events, participants discussed cultural connections between local Aboriginal peoples and the world. Since a 1987 piece discussing the origins of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples, Taiwan Panorama has on multiple occasions extended coverage to the Austronesian world, reporting on cultural connections between Taiwan’s Aboriginal peoples and other ethnic groups including the Maori of New Zealand and Indigenous Hawaiians. A 2022 story, “Tattooing Without Machines” highlighted the similar hand-tapping tattooing cultures of the Paiwan people and the Marshall Islands.

The Paiwan tattooist Cudjuy Patjidres is shown here teaching traditional “hand-tapping” tattooing techniques to students from the Marshall Islands and Tahiti, whose Indigenous inhabitants, like Taiwan’s, are Austronesian peoples. (photo by Lin Min-hsuan)

The Paiwan community of Timur in Pingtung’s Sandimen Township put up wood sculptures and traditional slate slab houses, creating a strong Aboriginal ambience.

Old wisdom and future solutions

In recent years, society has shown renewed interest in the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the land.

The knowledge and uses of nature among Indigenous peoples—so-called “ancient” traditional wisdom—have been reinterpreted as a potential source of solutions for “modern” sustainable development. From “The Wisdom of a Maritime People: Keeping Lanyu’s Tao Culture Alive” and “Living in Harmony with the Forest” to “Sustainable Food Wisdom—The Foraging Culture of the Amis People,” Taiwan Panorama has covered efforts to restore millet cultivation and native tree species and reclaim traditional life skills in architecture as well as cloth and bamboo weaving, showing how traditional Aboriginal knowledge can provide society with clues to a better future.

Taiwan Panorama’s long-running coverage of Indigenous issues has been a microcosm of social change on the island, revealing how Indigenous peoples have adapted their cultures and ideas to social transformations and are continuing to write stories that are part of the fabric of Taiwan.

Waitresses at this restaurant wear traditional Seediq attire as they serve creative dishes featuring Indigenous flavors.

Millet is a traditional staple for Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples and a symbol of their cultures. Some Bunun farmers are cultivating it using toxin-free methods.