Elective course 102: The Ethics of the Chinese Student-TeacherRelationship . . . . . . 1 credit

Jenny Hu / tr. by Robert Taylor

December 1995

In traditional Chinese society, the teacher ranked beside "Heaven, Earth, Monarch and Parents" as the partner in one of the "Five Human Relationships." The teacher's exalted status was on a par with that of the monarch, and to "betray one's teacher" was as unconscionably immoral an act as killing one's own parents, for the teacher represented unchallengeable authority.

Why did the Chinese hold teachers in such great respect? And just what is meant by the Chinese shidao-the code of behavior governing the relationship between teacher and students? How was such a tradition able to continue uninterrupted for two millenia?

In old-style Chinese families, in the central room of the house there would usually hang a long scroll inscribed: "Heaven, Earth, Monarch, Parents, Teacher," with incense smoldering in a burner in front of it. The reverence which this expressed needs no further explanation.

Professor Kung Peng-cheng of the Department of History at National Chung Cheng University says that in Chinese society, "Heaven, Earth, Monarch, Parents, Teacher" symbolize the important elements in the development of a person's life. "Heaven and Earth" provide the natural conditions for human life, "Monarch" symbolizes the state and society on which people depend for their existence, and "Parents" are the source of blood ties, while the "Teacher" shoulders the great and heavy responsibility of initiating a person into cultural life.

"From the point of view of cultural transmission, the 'teacher' is equivalent to another set of parents. That people should respect their teachers just as they should love their country and honor their father and mother is seen as an unimpeachable moral principle," says Kung Peng-cheng. But the difference between this relationship and the other four is that "teachers can be chosen."

Shared convictions

Many teachers today lament that the "teachers' ethical code has disappeared." But looking back into the past, "the teacher-student relationship involved both 'teachers' and 'students.' In other words, it comprised both 'the behavior expected of the teacher' and 'the behavior expected of the student,'" says folk music scholar Lin Ku-fang. Today many teachers focus on the change in the way students behave towards teachers, but in fact the role of the teachers themselves has also departed from their traditional one. "Education today involves a division of labor into different fields of knowledge, but in the past education was 'holistic' and attempted to impart principles of benevolence, forbearance, etiquette and justice, and the teacher had to teach by example."

Ancient Chinese writings define the "teacher" in very broad terms. The Book of Rites says: "The teacher is one who imparts knowledge and relates it to virtue." The Analects says: "One who reviews the old and reaches new understanding can serve as a teacher." Chinese society regarded the "teacher" as one who put both knowledge and morality into practice, and what students came to him to learn was not only knowledge, but usually and more importantly this spirit of its practical application.

From another point of view, "in the past students were the cream of society," says Chen Chuo-min, principal of National Changhua University of Education. He notes that although Confucius was said to advocate education for the common people and teaching all without discrimination, in fact the students who would come forward to be taught basically all had an intense desire to learn, and thus can be seen as a highly motivated segment of the population.

A teacher's reputation was built on his moral virtue and his writings, and students would come to study because they admired the teacher's beliefs and strength of character. This was the basis for the superb teacher-student relationship in China in historical times. Because teacher and students spent long periods together, sometimes even living under the same roof, the teacher had the opportunity to gain a deep understanding of every student's character, and could adapt his teaching to the students' abilities, giving them the feeling of being bathed in constant solicitude. Character-building education was achieved naturally through daily life.

"Students could see with their own eyes their teacher's character and the way he applied moral principles, and this naturally convinced them and kindled their admiration and their desire to be close to him." Architect Wang Chen-hua, who gives classes in the classics at his Te-chien Academy, says that in the past, students were called dizi or "brother-son" (both younger brother and son), and the teacher was called shifu or "teacher-father" (both teacher and father)-teachers and students became "like family." Thus it was quite natural that students willingly did all kinds of chores for their teacher, such as emptying his spittoon.

In Chinese history, the shuyuan or "academy" typified this teacher-student relationship. The principal of an academy held his position by dint of his moral virtue and scholarship, and attracted students who shared his convictions.

Mainland Chinese cultural historian Yu Qiuyu writes in his Notes From a Mountain Retreat that when Southern Song philosopher and educator Zhu Xi(1130-1200, one of the founders of the Neo-Con-fucianist "School of Laws") gave instruction at his Yuelu Academy, "so many students and followers flocked to hear him that there was nowhere for them all to be seated." When Zhu Xi became the victim of false accusations in a political plot against him, his students and followers also suffered as a result. Zhu's most outstanding student, Cai Yuanding, preferred to be arrested rather than recant against his teacher and his doctrines, and later died on the way into exile. Thus we can say he gave up his life for his teacher and his principles.

The teacher as patron

In identifying the reasons why the teacher-student ethic could be maintained in ancient times, apart from the teacher himself convincing others by his erudition and strength of character, "the authority of one' s seniors, which was created by the whole power structure, was an external factor which cannot be ignored," says Lin Ku-fang. Under this system of authority by seniority, one of the things most frowned upon was for someone to offend their seniors, and thus the ideal of "I love my teacher but I love truth more" as seen in the West was not extolled in China. In Chinese history there are many stories of students asking for a teacher's advice and explaining their future intentions, but it was very rare for teacher and student to engage in vigorous debate.

"In China, the teacher was the embodiment of truth. The doctrine was the teacher and the teacher was the doctrine," observes author Po Yang. Because of this, the Chinese also used to say that "to betray one's teacher is to destroy one's ancestors," and that "to rebel against the teacher is to betray morality." In other words, to betray one's teacher is to go against truth and is a moral outrage.

However, the invention of the imperial examination system brought about a new development in the teacher-student relationship, and also reinforced the status of the teacher. Successful candidates called the chief examiner at the examination venue "teacher," and called themselves "pupils." Thus teacher and students formed the core of civil service factions, and the teacher became a source of patronage for career advancement. "The 'teacher' was the patron who developed people's talents and secured promotion, and his 'pupils' were expected to feel a debt of gratitude and to do their best to repay it," says Po Yang. "Esteem for the teacher and his doctrines did not necessarily mean respect for knowledge. It could mean respect for someone's official rank."

"The culture of respect for the teacher had its ideal side and its practical side. The ideal side was the moral character of the scholar, while the practical side was the career prospects of the student," says Lin Ku-fang.

The student-teacher relationship was based on shared convictions and sometimes involved mutual benefit, and thus "a man's influence [was] measured by the number of his followers," and in Chinese history there have been innumerable instances of "factional strife" and "protecting one's own faction and attacking others." Perhaps kungfu novels which depict how a student of one master who wished to follow another might be branded a traitor and become the victim of a "cleaning of the ranks," subtly reflect the state of the real world. "This is an 'alienation' of the student-teacher relationship," says Lin Ku-fang.

The teacher's greatness of character

But today, when speaking of "respect for the teacher," the image in many people's minds is still that of Confucius and his disciples. Although the era of "character-building education" is past and gone, the bonds between a teacher of strong character and his admiring students, as expressed in the lines "The blue mountains pierce the clouds/ The rolling river runs broad and deep/ But Master, your greatness of character/ Is as high as the mountains and as long as the river," remain the undying aspiration of many educators.

[Picture Caption]

p.24

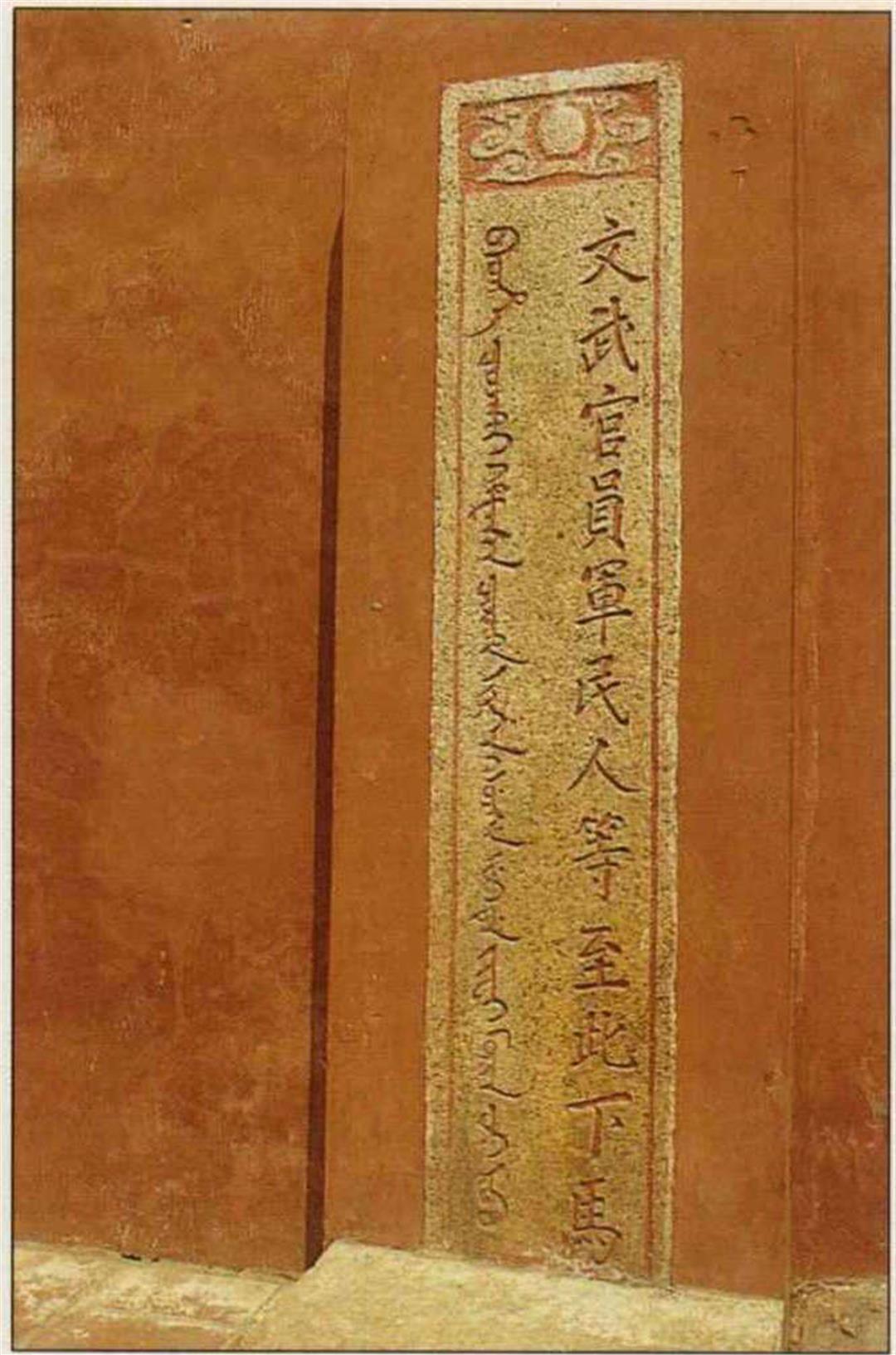

This plaque outside the Confucian temple in Tainan orders all comers, whatever their status, to dismount in deference to the great teacher. But has the sacred code which once governed teacher- student relations now become as much a thing of the past as this ancient monument? (photo by Vincent Chang)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)